Hurricane Bonnie (1998)

Hurricane Bonnie was a major hurricane that made landfall in North Carolina, United States, inflicting severe crop damage. The second named storm, first hurricane, and first major hurricane of the 1998 Atlantic hurricane season, Bonnie developed from a tropical wave that emerged off the coast of Africa on August 14. The wave gradually developed, and the system was designated a tropical depression on August 19. The depression began tracking towards the west-northwest, and became a tropical storm the next day. On August 22, Bonnie was upgraded to a hurricane, with a well-defined eye. The storm peaked as a Category 3 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale, and around the same time, the storm slowed and turned more towards the north-northwest. A large and powerful cyclone, Bonnie moved ashore in North Carolina early on August 27, slowing as it turned northeast. After briefly losing hurricane status, the storm moved offshore and regained Category 1-force winds, although it weakened again on entering cooler waters.

| Category 3 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

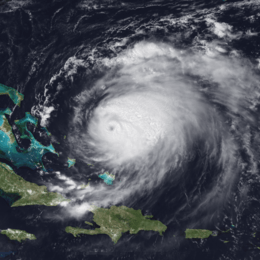

Hurricane Bonnie near peak intensity east of the Bahamas on August 23 | |

| Formed | August 19, 1998 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | August 30, 1998 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 115 mph (185 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 954 mbar (hPa); 28.17 inHg |

| Fatalities | 5 overall |

| Damage | $1 billion (1998 USD) |

| Areas affected | Leeward Islands, North Carolina, Mid-Atlantic States |

| Part of the 1998 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Fearing a major hurricane strike, coastal locations from Florida to Virginia performed extensive preparations in advance of the storm. In addition to tropical cyclone watches and warnings, about 950,000 people were evacuated from the Carolinas, and the military evacuated and relocated hundreds of aircraft and vessels from the storm's projected path. Soldiers and guardsmen were deployed throughout those regions.

Hurricane Bonnie made landfall as a borderline Category 2–Category 3 storm, with intense wind gusts of up to 104 mph (167 km/h) and rainfall peaking at about 11 in (280 mm). Reports of downed trees and powerlines, as well as structural damage such as blown-out windows and torn-off roofs, were reported. In coastal North Carolina, the storm washed ashore tens of thousands of tires that had been part of an artificial reef. Crop damage was extensive, but the storm was overall less severe than initially feared. Total damage was estimated at $1 billion (1998 USD).

Meteorological history

On August 14, 1998, a tropical wave emerged off the west coast of Africa just north of Dakar and moved westward across the Atlantic Ocean. Initially located within cool waters, a strong high pressure area steered the disturbance on a west-southwest track over warmer waters, and convection started to develop. Several small centers of rotation existed within a broad circulation, and at 1200 UTC on August 19, the centers consolidated and the disturbance became sufficiently organized to be declared a tropical depression. Despite being poorly organized, winds slightly to the north of the system's center approached tropical storm strength shortly thereafter.[1] Ship reports revealed a closed circulation, though the center was elongated in a northwest–southeast oriented manner. Upper-level winds were favorable, which suggested that intensification was likely. The cyclone began moving on a northwestward track,[2] and just hours later the center of circulation appeared to reform close to the convection, an indication of a strengthening storm, as good outflow existed over the western side of the storm.[3] Deep convection slowly developed closer to the center,[4] and at 1200 UTC on August 20, the depression was upgraded into Tropical Storm Bonnie as it continued its west-northwest track around the periphery of a high pressure system over the Leeward Islands.[1]

Late on August 20, the first reconnaissance plane entered the storm and found a minimum central barometric pressure of 1001 mb. The storm brushed the Leeward Islands, although the main thunderstorm activity remained to the north of the storm over the open ocean.[1] Bonnie began to organize its broad circulation early on August 21,[5] and within the next day the storm began to intensify. The storm began to look strong on satellite images with banding features over the north and west quadrants.[6] The Hurricane Hunters aircraft found a minimum pressure of 987 mb and a nearly complete eyewall early on August 22, and as a result, the tropical storm was upgraded to hurricane status.[7] Bonnie slowed in forward speed, coinciding with previous forecasts.[8] Later that day, storm was upgraded to a Category 2 on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale, which occurred with a substantial 15 mb drop in 8 hours. At the same time, steering currents weakened with the dissipation of the high pressure system; this, combined with the effect of a nearby trough, caused the storm to turn in a more north-northwestward direction around the western periphery of an anticyclone to the east.[9] Bonnie became a Category 3 storm, a major hurricane, at 1200 UTC the next day, reaching its peak winds of 115 mph (185 km/h) at the same time.[1]

A mid- to upper-level trough slowed the storm almost to a halt early on August 23,[10] before a drift to the north-northwest began. The next National Hurricane Center (NHC) advisory then reported that the eye was becoming more distinct and well-defined. This strengthening trend abated because the storm had churned up the waters over which it was passing, bringing cooler water to the surface as a result of the slow track. Another inhibiting factor may have been related to the same trough that caused the northward turn, though due to a large anticyclone situated over the hurricane, the weakening effects were not substantial.[11] Despite wind shear, the large and powerful circulation resisted weakening for a time.[12] Early on August 25, the shear and the entrainment of drier air into the hurricane took its toll on Bonnie, giving it a ragged appearance on satellite imagery, and the eye briefly became cloud-filled.[13]

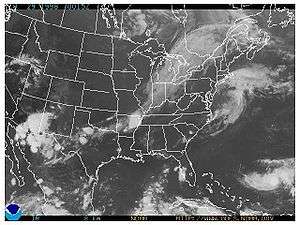

The storm accelerated somewhat by August 26, and early that day, it was moving at about 14 mph (23 km/h).[14] An approaching mid-level trough steered Bonnie north-northeast, and at 2100 UTC on August 26, the eye passed east of Cape Fear, North Carolina. The hurricane once again slowed, and early the next day, it made landfall near Wilmington, North Carolina as a strong Category 2 hurricane.[1] Doppler weather radar displays estimated that maximum sustained winds had quickly weakened to below hurricane intensity, and the storm was briefly downgraded to a tropical storm.[15] However, as the storm turned towards the east in response to the approaching trough, the center neared open waters and the winds began to re-intensify.[16] As a result, the cyclone re-attained hurricane status at 0000 UTC on August 28.[1] Offshore, the center began drifting roughly eastward.[17] Entering colder waters, hurricane status was lost at 1800 UTC that day, followed by an acceleration to the northeast.[1] The storm began to lose deep thunderstorm activity, and was forecast to lose tropical characteristics and become an extratropical cyclone within days.[18] By early on August 29, little connection remained over the western semicircle,[19] and only a band of such activity persisted to the southeast of the center.[20] Bonnie became extratropical around 1800 UTC on August 30, to the southeast of Newfoundland.[1]

Preparations

On August 20, a tropical storm watch was posted for the islands of Antigua, Barbuda, Anguilla, St. Maarten, Saba and St. Eustatius, though it was discontinued the next day. Shortly thereafter, a tropical storm warning was issued for the U.S. and British Virgin Islands. Tropical storm warnings and hurricane watches were put into effect for the Turks and Caicos Islands and the southeastern Bahamas. By August 24, those tropical cyclone advisories were discontinued, and at the same time they were issued for parts of the Southeast United States. A hurricane warning was eventually posted for Murrells Inlet, South Carolina to the North Carolina – Virginia border. On August 27, tropical cyclone watches and warnings extended as far north as Plymouth, Massachusetts; all were discontinued early on August 29.[1]

Florida and South Carolina

Initially the storm posed a threat to Florida, where military officials kept abreast of the situation. Heavy surf advisories were posted from central portions of the state northward to Georgia, and the National Hurricane Center advised that swimming and boating should be avoided. The Mayport Naval Station ordered 25 ships out to sea in advance of the approaching storm. The Salvation Army was on standby in Jacksonville, prepared to act when needed.[21] Hardware stores in the state reported up to a 75% increase in the sales of emergency supplies.[22]

Some computer forecast models initially predicted that the storm would move towards South Carolina or Georgia.[23] Before the storm's arrival in South Carolina, researchers at Clemson University used Bonnie to test a new method of estimating the damage a storm is likely to cause.[24] In the state, the South Carolina National Guard put about 1,512 men on active duty, 1,474 being of the Army National Guard.[25] On August 25, the South Carolina Emergency Preparedness Division activated Level 1 operations, the highest of five levels. That same day, the State Governor declared a State of Emergency, calling for mandatory evacuations of residents east of U.S. Route 17 in Horry and Georgetown counties. Schools were closed throughout the state.[26] Over 200,000 people were evacuated from those counties, of which 120,000 were tourists.[27] About 6,000 sought shelter at schools in Horry County.[28] In a survey, 12% of respondents in the state took traffic as a significant consideration in deciding if they should evacuate.[29] On the Grand Strand, Bonnie was the first storm where buses were provided to help people evacuate.[30]

North Carolina and Virginia

About 815 guardsmen were called to North Carolina, where they assisted local authorities with the extensive preparations, including evacuating 750,000 state citizens.[25] Mandatory and voluntary evacuations were ordered for part of the state.[31] The Outer Banks experienced extensive evacuations; at least 300,000 left, bringing traffic on highways from there to the mainland to a standstill.[27] Active duty armed forces were set to support hurricane recovery missions, and four Defense Coordinating officers were notified. Defense Department emergency centers were opened starting August 21. Additionally, the U.S. Atlantic Command activated their 24-hour response cell.[25] Soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Marines evacuated equipment, including hundreds of vessels and aircraft.[25] The North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources closed several state parks, all three state aquariums, and the Division of Marine Fisheries office, with plans to reopen primarily once storm-related damage at any of the locations was properly addressed.[32]

A study was performed on the storm in eight counties in North Carolina to determine the cost of evacuation for hurricanes, and included 1,029 households.[33] Another study was performed regarding the actions taken during Hurricane Bonnie evacuations in the state. Tourists were interviewed, and it was found that 90% of vacationers who were threatened by the hurricane evacuated, of which 56% went home, 3% stayed in public shelters, 22% stayed with friends or relatives, 3% stayed in hotels and motels, and 16% stayed elsewhere. In total, 58% stayed within North Carolina, 12% went to Virginia, 6% relocated to South Carolina, and 24% stayed in other regions. Most of the evacuees left on August 25; 80% left with their own vehicles, and 18% used rental transportation.[34] Officials in the state opened an estimated 100 shelters to accommodate the evacuating tourists and residents.[35]

In Virginia, where 15 jurisdictions declared local emergencies, local governments took action to inform and protect citizens. Residents in mobile home parks, as well as campgrounds, were advised to evacuate, and 13 jurisdictions opened shelters by August 26. State Governor Jim Gilmore declared a State of Emergency, and as a result, the State Emergency Operations Center was activated. Beaches and piers were shut down in Virginia Beach, Hampton, and Gloucester counties, where communities canceled some local events due to the threat of Bonnie. Voluntary evacuations throughout the state were issued, and some hotels reached maximum capacity as a result.[36] Roughly 60 Navy ships were ordered to leave port at Norfolk, and ride out the storm far out to sea.[37] The State of Virginia banned swimming along the coast.[31] As Bonnie progressed northward, a tornado watch was posted for much of eastern Virginia.[38]

Impact

While located north of the Caribbean Sea, Bonnie dropped light rainfall in Puerto Rico.[1] The storm also produced heavy rainfall and gusty winds in The Bahamas, though no significant damage was reported.[39] Along the U.S. East Coast, two swimmers drowned in rip currents; numerous others were rescued.[23] In the United States, Bonnie caused an estimated $1 billion in damage.[40]

South Carolina

As the hurricane passed to the east of the state, rainfall ranged from 2 to 4 in (51 to 102 mm), and storm surge was around 2 to 3 ft (0.61 to 0.91 m).[41] The highest recorded wind gust in the state was 82 mph (132 km/h) at the Cherry Grove pier, and sustained winds peaked at 76 mph (122 km/h) at the Myrtle Beach Pavilion. Damage was widespread in Horry County, where downed trees and power lines and structural damage was reported.[42] The high winds blew down several trees in Charleston County,[43] and tore the roof off a strip mall in North Myrtle Beach.[44] A 50-year-old man died near Myrtle Beach; he was electrocuted while checking his generator after a power outage.[45] Along the coast, a 25-year-old man died in rip currents at Surfside Beach.[23] Total damage in South Carolina was estimated to be around $25 million (1998 USD).[1]

North Carolina

Hurricane Bonnie came ashore just at or below major hurricane intensity, bringing with it intense wind gusts of up to 98 mph (158 km/h) in North Carolina,[1] though offshore at the Frying Pan Shoals Light Tower, winds reached 104 mph (167 km/h).[40] The strongest winds were found in the precursor rainbands, where localized downbursts caused severe damage.[1] Sustained winds officially peaked at 51 mph (82 km/h) at Elizabeth City, where gusts reached 63 mph (101 km/h). Rainfall was heavy as a result of the storm's slow movement, peaking at 11 in (280 mm) at Jacksonville, while several totals of over 10 in (250 mm) were reported. However, because the area had been experiencing drought conditions, the flooding was not as severe as it could have potentially been. The most significant flooding occurred near the Cape Fear River, where high waters were reported. The highest storm surge occurred along the beaches of Brunswick County, mostly reaching 5 to 8 ft (1.5 to 2.4 m) above average.[1] Elsewhere, flooding was mostly limited to locations with poor drainage and low-lying areas.[46] Coastal flooding was not widespread, though surge in the Pungo River flooded several local homes. Other coastal flooding was reported in various harbors and coastal cities. Part of North Carolina Highway 12 was flooded and closed on Hatteras Island due to tidal flooding. At North Topsail Beach, many of the protective dunes constructed after Hurricane Fran in 1996 were destroyed, and along the Bogue Banks, tens of thousands of tires, part of an artificial reef, were washed ashore.[46]

One direct death occurred in North Carolina; a young girl was killed when a tree fell on her Currituck County home. Throughout eastern portions of the state, trees and powerlines were downed, and there were reports of structural damage.[1] Numerous docks, piers and bulkheads were either damaged or destroyed, including the Iron Steamer and Indian Beach piers, which both lost large sections to the strong wind and surf.[46] Due to the winds, the Brunswick Community Hospital lost about 3,000 sq ft (280 m2). of roof and an air conditioner.[47] The storm left about 500,000 people in the state without electric power.[40] In some areas, vegetative and structural debris accumulated in piles several feet deep; it is reported that thick underbrush prevented the debris from traveling further inland.[48] Wilmington "turned into a disaster zone", with flooded highways, and downed trees lying across roadways.[49] Crop, particularly tobacco, damage was extensive.[46] According to then-governor Jim Hunt, "You fly along and don't see much damage to the beach houses, and it's easy to think we didn't have much damage. But then you look at the tobacco in fields and you know the damage has been extensive." The crop losses accounted for much of the overall damage.[50] Forty-seven of those who failed to evacuate in time sought shelter in the Bald Head Island lighthouse as the worst of the storm bore down.[51] Despite the effects, Bonnie's impact was actually less than originally predicted.[52] Overall, property damage in the state is estimated at $240 million (1998 USD), with significantly higher crop damages.[1]

Several locations received significant physical impacts. On Wrightsville Beach, North Carolina, Bonnie's erosion caused an inlet to migrate further south. On the northern end of the inlet, a large sand bar developed, partially due to the storm moving offshore sand. Dune sediments were lost during the storm, exposing boardwalk piling. Similarly, on Topsail Beach, North Carolina, the storm breached 27 sand dunes, destroying 60% of the dune line.[53] Sediment from storm washover measured 50 cm (20 in) thick behind the beach. Sections of many eroded dunes were re-built using truck loads of sand. Strong waves ran through the foundation of two stilted homes, both of which were later reinforced to compensate for the lost sand.[54]

Virginia

Bonnie passed just offshore of southeast Virginia, lashing the region with heavy rain and high winds. Sustained winds reached 81 mph (130 km/h) at Cape Henry, and gusts peaked at 104 mph (167 km/h). There were other reports of winds over 80 mph (130 km/h) along the coast. Numerous homes suffered damage in the Hampton Roads area, and near Virginia Beach, winds blew windows out in hotels. Storm surge was generally around 2 to 4 ft (0.61 to 1.22 m) with some higher reports, causing some coastal flooding. Rainfall was moderate to heavy, ranging from 1 to 7 in (25 to 178 mm), with the higher-end totals occurring in the Norfolk area.[55]

Between 320,000 and 650,000 customers lost power in the state.[56][57] The power outages led to decreased production in some water and sewer plants, prompting local officials to advise residents to conserve water. In the Ocean View section of Norfolk, the winds tore the roofs off two apartment complexes, and damaged siding on other structures. Along the coast, boats were ripped from their moorings.[50]

Throughout the Tidewater region, there were estimates of thousands of downed trees, and hundreds of homes and businesses were damaged. Of these, about 40 structures were declared uninhabitable. Debris was blown several blocks inland from the coast. Among the hardest hit locations was Sandbridge, where about 12 homes were severely damaged. It is reported that the state was unprepared for the damage, expecting a strike from a weakened tropical storm. About $15.3 million (1998 USD) in damage was inflicted in the Virginia Beach and Norfolk areas.[58] Throughout the state, insured losses totaled $95 million (1998 USD).[59]

Mid-Atlantic, New England and Atlantic Canada

As the storm moved offshore, outer rain bands affected the Maryland coast with gusts of up to 42 mph (68 km/h) at Ocean City, and waves of 10 ft (3.0 m). No damage was reported.[60] Light rainfall was also reported northward into Delaware and New Jersey.[1] In addition, up to 0.2 in (5.1 mm) of precipitation extended into New York.[61] A person was caught in rip currents and drowned near Rehoboth Beach, Delaware.[1] Along the coast of New Jersey, Bonnie produced strong waves and rip currents, resulting in hundreds of water rescues and eight injuries. The storm was at its closest position to the state on August 28, as it passed 140 mi (230 km) to the east of Atlantic City, although the rough surf began several days prior, on August 23. Numerous beaches were closed, and swimming was banned in several communities, as well. The state also reported moderate wind gusts, generally peaking at 35 mph (56 km/h). Only minor beach erosion occurred.[62] At Point Pleasant Beach, New Jersey, there were reports of a drowning in the rough seas caused by the storm; however, the man was later spotted onshore with his fiance, and the two were charged with filing a false police report.[63]

Bonnie moved well to the south of Cape Cod, although a significant outer rain band affected southern Plymouth County, Massachusetts. Torrential downpours produced 4 in (100 mm) of precipitation at Whitehorse Beach, and other locations reported over 1 in (25 mm). Winds reached 25 to 35 mph (40 to 56 km/h), although offshore the Georges Bank Buoy reported a 52 mph (84 km/h) gust. A man was killed when his rowboat capsized in rough surf of 1 to 2 ft (0.30 to 0.61 m); his companion safely swam to shore.[64][65]

On the afternoon of August 29, Bonnie entered the Canadian Hurricane Centre's area of responsibility as a tropical storm, and passed south of Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. Precipitation along the coast of Nova Scotia ranged from 15 to 25 mm (0.59 to 0.98 in) and winds gusted to around 102 km/h (63 mph). Slightly higher gusts were reported off the coast. On Sable Island, the storm dropped 30 mm (1.2 in) of rainfall. An offshore buoy recorded a wave height of 17.9 m (59 ft).[66]

Aftermath and observation

Following the hurricane in North Carolina, 10 counties were declared federal disaster areas,[67] while 30 counties became eligible for public and individual assistance.[68] Shelters were opened in 11 counties, and the Raleigh-Durham International Airport briefly canceled all flights.[69] To remove the tens of thousands of tires that washed ashore, hundreds of inmates from state prisons were sent to the Bouge Banks. Some of the tires were buried in sand, and could only be removed during low tide. About 700 more state prisoners were sent around the state to clear debris, and 39 inmate crews were deployed to help farmers salvage the severely damaged tobacco fields.[70] In South Carolina, Horry County was declared a federal disaster area due to the damage.[42] In Virginia, the cities of Chesapeake, Norfolk, Portsmouth, Suffolk, and Virginia Beach became eligible for individual and public assistance programs.[71] After the storm's departure, a thunderstorm temporarily halted power restoration by Virginia Power company crews.[72] Virginia Governor Jim Gilmore allowed for over $11 million (1998 USD) in state and federal funds to help five cities recover.[73] The storm also contributed to a 13.6% decline in home sales across the southern United States during the month of August by "discouraging potential home buyers" in coastal areas.[74]

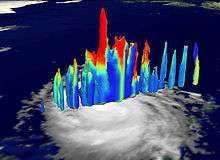

Both during and after Hurricane Bonnie's onslaught, analysis of the storm was extensive; it was deemed "the most observed hurricane in history." When examined with Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) satellite imagery, it was discovered that peak cloud tops surrounding the eyewall rose 59,000 ft (18,000 m) into the atmosphere, twice as tall as Mount Everest. This was the first time that TRMM had observed such a tropical cyclone structure, according to co-developer of the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale, Bob Simpson.[75] The storm was also used for collection of tropical cyclone research data. For the first time in the Atlantic, a fleet of aircraft investigated the storm's upper-levels, while other aircraft flew into the low- and middle-levels. A record of over 500 parachute sensors were dropped into the storm while it was active. Each costing $600 (1998 USD), they sent storm data to research centers via Global Positioning System.[76]

During the storm, the Weather Channel web site experienced substantially increased traffic. Up from an average of three million views per day, 10 million page views on August 26 led to slow download times on the website. On seven major weather providers, page views increased by 123% from August 24 – August 26, compared to an equal period of time during the previous week.[77]

See also

- Hurricane Arthur

- Other storms of the same name

- List of North Carolina hurricanes (1980–1999)

- List of Delaware hurricanes

- List of New Jersey hurricanes

- List of Maryland hurricanes

- List of New England hurricanes

References

- Lixion A. Avila (October 24, 1998). "Hurricane Bonnie Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 17, 2008. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Pasch (August 19, 1998). "Tropical Depression Two Discussion Number 1". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Guiney & Mayfield (August 19, 1998). "Tropical Depression Two Discussion Number 2". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Rappaport (August 20, 1998). "Tropical Depression Two Discussion Number 3". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Avilia (August 21, 1998). "Tropical Storm Bonnie Discussion Number 8". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Mayfield (August 21, 1998). "Tropical Storm Bonnie Discussion Number 10". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Rappaport (August 22, 1998). "Hurricane Bonnie Discussion Number 11". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Avilia (August 22, 1998). "Hurricane Bonnie Discussion Number 13". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Mayfield (August 22, 1998). "Hurricane Bonnie Discussion Number 14". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Pasch (August 23, 1998). "Hurricane Bonnie Discussion Number 16". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Pasch (August 23, 1998). "Hurricane Bonnie Discussion Number 18". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Pasch (August 24, 1998). "Hurricane Bonnie Discussion Number 21". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Rappaport (August 25, 1998). "Hurricane Bonnie Discussion Number 25". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Pasch (August 25, 1998). "Hurricane Bonnie Discussion Number 28". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Rappaport (August 27, 1998). "Tropical Storm Bonnie Discussion Number 35". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Rappaport (August 27, 1998). "Tropical Storm Bonnie Discussion Number 36". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Lawrence (August 28, 1998). "Hurricane Bonnie Discussion Number 38". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Rappaport (August 28, 1998). "Tropical Storm Bonnie Discussion Number 41". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Lawrence (August 29, 1998). "Tropical Storm Bonnie Discussion Number 42". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Jarvinen (August 29, 1998). "Tropical Storm Bonnie Discussion Number 43". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Derek L. Kinner (August 23, 1998). "Hurricane Bonnie adds some punch". The Florida Times-Union. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Craig Hampshire (August 25, 1998). "Hurricane Bonnie's threat causes sales increase". University Wire. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Jessica Robertson (August 24, 1998). "Hurricane Bonnie Threatens U.S. Coast -- Two Drown, Dozens Rescued". The Seattle Times. Retrieved November 6, 2008.

- Clemson University (August 27, 1998). "Researchers Plot Hurricane Damage Zipcode By Zipcode". Science Daily. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense (Public Affairs) (1998). "Department of Defense Prepares for Hurricane Bonnie". U.S. Department of Defense. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Joe Farmer (August 26, 1998). "Preparations Being Made In Anticipation Of Effects From Hurricane Bonnie" (PDF). South Carolina Emergency Preparedness Division. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 7, 2008. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Estes Thompson (1998). "Bonnie forces N.C. evacuation" (PDF). Associated Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 4, 2014. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Staff Writer (August 30, 1998). "Shelters Equal to Tough Task Some Concerns to be Addressed". Sun News. Retrieved November 7, 2008.

- Dow, K.; Cutter, S. L (1998). Crying wolf: Repeat responses to hurricane evacuation orders. Coastal Management. pp. 26, 237–252.

- Steve Porter (1998). "Hurricane evacuation takes wheels and gasoline". Myrtle Beach Herald. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Staff Writer (November 13, 1998). "Evacuation ordered as Bonnie picks up speed". CBC News. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- "DERN Closes Facilities in Preparation for Hurricane Bonnie". N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources. August 26, 1998. Archived from the original on October 24, 2008. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Whitehead, J. C. (1998). "One million dollars a mile?". Societal Impacts Program. Archived from the original on July 13, 2007. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- "Chapter Four: Behavioral Assumptions for the Evacuation of Tourists in North Carolina". FEMA & U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Archived from the original on January 9, 2009. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- "Hurricane Bonnie Gets Hams' Attention". American Radio Relay League. August 31, 1998. Archived from the original on January 12, 2005. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Janet L. Clements (August 26, 1998). "Virginia Localities and the State Prepare for Hurricane Bonnie". Virginia Department of Emergency Services. Archived from the original on June 16, 2007. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- J R. Moehringer (August 26, 1998). "Half a Million Try to Escape Bonnie's Wrath". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Janet L. Clements (August 27, 1998). "Hurricane Bonnie Slowly Heads Towards Virginia—Tornadoes Possible". Virginia Department of Emergency Services. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Associated Press (August 21, 1998). "Hurricane Bonnie Gathers Speed". CBS News. Retrieved October 25, 2008.

- National Climatic Data Center (1998). "Bonnie Buffets North Carolina!". NOAA. Archived from the original on September 16, 2008. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- "Natural Hazards That Significant Impact Horry County" (PDF). Horry County. 1998. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 19, 2011. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- National Climatic Data Center (1998). "Hurricane Bonnie Event Report for South Carolina (2)". Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- National Climatic Data Center (1998). "Hurricane Bonnie Event Report for South Carolina". Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Staff Writer (2008). "That was then: August 1998: Hurricane Bonnie". The State. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Staff Writer (November 13, 1998). "Tropical storm Bonnie heads for Nova Scotia". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- National Climatic Data Center (1998). "Hurricane Bonnie Event Report for North Carolina". Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- National Climatic Data Center (1998). "Hurricane Bonnie Event Report for North Carolina (2)". Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- David M. Bush (January 15, 1999). "Impact of Hurricane Bonnie (August 1998)". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved 2008-09-22. Check date values in:

|year= / |date= mismatch(help) - Sue Anne Pressley (1998). "Residents Flee as Hurricane Bonnie Lashes North Carolina". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Staff Writer (June 11, 1999). "Bonnie batters N.C., southeast Va". USA Today. Retrieved 2008-09-22. Check date values in:

|year= / |date= mismatch(help) - J R. Moehringer; Edith Stanley (August 27, 1998). "Hurricane Cuts Slow, Violent Path in N.C." Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Paul Nowell (August 28, 1998). "Bonnie's Impacts Less Than Expected". St. Paul Pioneer Press. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- "After Hurricane, Loss of Beach to Erosion Appears to Be Inevitable". The New York Times. August 31, 1998. p. A10.

- Melissa L. Tollinger; Deborah Dixon (1999). "Assessing "Practical Knowledge" of FEMA's Responsiveness Effectiveness in the Aftermath of Hurricane Bonnie, in Wrightsville Beach and Topsail Island, North Carolina". East Carolina University Department of Geography. Archived from the original on October 10, 2012. Retrieved November 3, 2007.

- National Climatic Data Center (1998). "Hurricane Bonnie Event Report for Virginia". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- "Virginia Hurricanes". Virginia Department of Emergency Management. Archived from the original on September 4, 2005. Retrieved 2008-09-22.

- "Natural Gas Keeps the Power on When the Electricity Fails- Gas Generators Provide Safe Alternative Source of Electricity for Homes and Small Businesses When the Power Goes Out". Virginia Natural Gas. April 16, 2002. Archived from the original on July 23, 2008. Retrieved October 28, 2008.

- Eric Wee; Lyndsey Layton (August 29, 1998). "Tidewater in Turmoil After Bonnie's Surprise". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 28, 2008.

- Amanda Levin (September 7, 1998). "Insured Losses From Hurricane Bonnie Total $360 Million". AllBusiness.com.

- Staff Writer (August 29, 1998). "Storm Briefly Regains Hurricane Status, Brushes Virginia and Then Heads Out to Sea". New York Times. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Roth, David M; Weather Prediction Center (2012). "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall in the Mid-Atlantic United States". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Point Maxima. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- National Climatic Data Center (1998). "Hurricane Bonnie Event Report for New Jersey". Archived from the original on June 18, 2008. Retrieved November 27, 2007.

- Don Singleton (August 29, 1998). "Man In Drowning Scare Nabbed on Dry Land". New York Daily News. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- "Hurricane Bonnie Event Report for Massachusetts". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved November 1, 2008.

- Staff Writer (August 30, 1998). "Body of Missing Boater Found Off Mass". United Press International. Retrieved November 1, 2008.

- Craig Clarke. "Canadian Tropical Cyclone Season Summary for 1998". Canadian Hurricane Centre. Retrieved October 14, 2009.

- Kevin Sack (August 28, 1998). "Too Much Relief, Hurricane Fails to Live Up to Potential". New York Times. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- "Designated Counties for North Carolina Hurricane Bonnie". FEMA. August 27, 1998. Archived from the original on October 21, 2008. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- "Division of Emergency Management". State of North Carolina. 1998. Archived from the original on May 5, 2001. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- "State prisoners to clean up tires littering Bogue Sound". North Carolina Department of Correction. August 31, 1998. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- "Designated Counties for Virginia Hurricane Bonnie". FEMA. 1998. Archived from the original on October 21, 2008. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Steve Stone (August 31, 1998). "Hurricane Bonnie Why Did We Drop Our Guard? The Aftermath While 90% now Have Electricity, a Few May Not Till Wednesday". The Virginian Pilot. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved October 26, 2008.

- Jon Frank (February 17, 1999). "Gilmore Frees up Relief Funds". The Virginian-Pilot. Retrieved November 3, 2008.

- Duff, Christina (October 1, 1998). "New-Home Sales Fell 4.4% in August, Hurt by Hurricane Bonnie in the South". The Wall Street Journal. p. 1.

- "Hurricane Bonnie was taller than Mt Everest". BBC News. September 2, 1998. Retrieved October 25, 2008.

- Paul Hoversten (August 30, 1998). "Bonnie yields data 'gold mine'". USA Today. Retrieved October 25, 2008.

- Matt Richtel (September 3, 1998). "NEWS WATCH; Heavy Weather: Hurricane Bonnie a Big Draw". The New York Times. Retrieved October 25, 2008.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hurricane Bonnie (1998). |