Tropical Storm Hermine (1998)

Tropical Storm Hermine was the eighth tropical cyclone and named storm of the 1998 Atlantic hurricane season. Hermine developed from a tropical wave that emerged from the west coast of Africa on September 5. The wave moved westward across the Atlantic Ocean, and on entering the northwest Caribbean interacted with other weather systems. The resultant system was declared a tropical depression on September 17 in the central Gulf of Mexico. The storm meandered north slowly, and after being upgraded to a tropical storm made landfall on Louisiana, where it quickly deteriorated into a tropical depression again on September 20.

| Tropical storm (SSHWS/NWS) | |

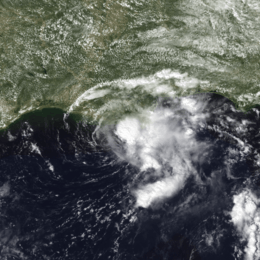

Tropical Storm Hermine on September 19, 1998 | |

| Formed | September 17, 1998 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | September 20, 1998 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 45 mph (75 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 999 mbar (hPa); 29.5 inHg |

| Fatalities | ~2 indirect[note 1] |

| Damage | $85,000 (1998 USD) |

| Areas affected | Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia |

| Part of the 1998 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Before the storm's arrival, residents of Grand Isle, Louisiana, were evacuated. As a weak tropical storm, damages from Hermine were light. Rainfall spread from Louisiana through Georgia, causing isolated flash flooding. In some areas, the storm tide prolonged the coastal flooding from a tropical cyclone. Gusty winds were reported. Associated tornadoes in Mississippi damaged mobile homes and vehicles, and inflicted one injury. While Hermine was not of itself a particularly damaging storm, its effects combined with those of other tropical cyclones, and resulted in agricultural damage.

Meteorological history

On September 5, 1998, a tropical wave emerged from the west coast of Africa and entered the Atlantic Ocean. The wave was not associated with any thunderstorm activity until it reached the Windward Islands, when cloud and shower activity began to increase. Continuing westward, the disturbance approached the South American coastline and turned into the northwest Caribbean. The wave interacted with an upper-level low-pressure system and another tropical wave that entered the region. At the time, a large monsoon-type flow prevailed over Central America, part of the Caribbean Sea, and the Gulf of Mexico.[1] An area of low pressure developed over the northwestern Caribbean, and at about 1200 UTC on September 17, the system was sufficiently organized to be declared a tropical depression in the central Gulf of Mexico.[1][2]

Initially, the cloud pattern associated with the system featured a tight and well-defined circulation, as well as clusters of deep convection south of the center. Due to the proximity of a large upper-level low-pressure area in the southern Gulf of Mexico, the surrounding environment did not favor intensification.[3] Influenced by the low, the depression moved southward.[4] The system completed a cyclonic loop in the central gulf,[1] and by early on September 18 was drifting northward.[5] As a result of wind shear, the center of circulation was separated from the deep convective activity.[6] Early the next day, deep convection persisted in a small area northeast of the center. Forward motion was nearly stationary, with a gradual drift east-southeastward.[7] Despite the wind shear, the depression attained tropical storm status at 1200 UTC on September 19; as such, it was named Hermine by the National Hurricane Center.[1]

Shortly after being upgraded to a tropical storm, Hermine reached its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 45 mph (75 km/h).[1] The tropical storm-force winds were confined to the eastern semicircle of the cyclone.[8] Hermine tracked northward and approached the coast, where it nearly stalled.[9] A continually weakening storm, it moved ashore near Cocodrie, Louisiana at 0500 UTC on September 20 with winds of 40 miles per hour (64 km/h), and then deteriorated into a tropical depression.[1] On its landfall, associated rain bands were deemed "not very impressive", although there was a rapid increase in thunderstorm activity east of the center. The thunderstorms produced heavy rainfall in parts of southeastern Louisiana and southern Mississippi. The storm progressively weakened as the circulation moved northeastward, and dissipated at 1800 UTC.[10] Initially, it was believed that Hermine's remnants contributed to the development of Hurricane Karl; however, this belief was not confirmed.[11]

Preparations

On September 17, the National Hurricane Center issued a tropical storm watch from Sargent, Texas to Grand Isle, Louisiana. The following day, the watch was extended southward from Sargent to Matagorda, Texas, and eastward to Pascagoula, Mississippi. A tropical storm warning was posted from Morgan City, Louisiana, eastward to Pensacola, Florida on September 19. The warning was promptly extended westward from Morgan City to Intracoastal City, Louisiana, and by 1200 UTC on September 20 all tropical cyclone watches and warnings were discontinued.[1] As the storm moved inland, flood advisories were issued for southern Mississippi.[10] On Grand Isle, a mandatory evacuation order was declared for the third time in three weeks,[12] and residents in low-lying areas of Lafourche Parish were ordered to leave.[13] Shelters were opened,[14] but few people used them. Only fifteen people entered the American Red Cross shelter in Larose, Louisiana, which had been designed to hold 500.[15] Workers were evacuated from oil rigs in the Gulf of Mexico,[16] and energy futures rose substantially in anticipation of the storm, though when Hermine failed to cause significant damage, they retreated.[17] The Coast Guard evacuated its Grand Isle station in preparation.[18]

Impact

In southern Florida, the combination of rainbands from Hermine and a separate upper-level cyclone in its vicinity produced up to 14.14 inches (359 mm) of rainfall.[19] Hermine's remnants spread showers and thunderstorms across northern parts of the state.[20] The heavy rainfall downed a tree Orlando, and led to several traffic accidents. A man died on U.S. Route 441 after losing control of his vehicle.[21]

Upon landfall in Louisiana, winds were primarily of minimal tropical storm-force and confined to squalls. Offshore, a wind gust of 46 miles per hour (74 km/h) was reported near the mouth of the Mississippi River, and near New Orleans, wind gusts peaked at 32 miles per hour (51 km/h). Along the coast, storm tides generally ran 1 to 3 feet (0.30 to 0.91 m) above normal, which prolonged coastal flooding in some areas from previous Tropical Storm Frances.[22] Winds on Grand Isle reached 25 miles per hour (40 km/h), and storm tides on the island averaged 1 foot (0.30 m).[23] Hermine brought 3 to 4 inches (76 to 102 mm) of rainfall to the state, triggering isolated flash flooding. Near Thomas, part of Louisiana Highway 438 was submerged under flood waters.[22] An oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico reported sustained winds of 48 miles per hour (77 km/h) with gusts to 59 miles per hour (95 km/h).[24]

.jpg)

At around 8:30 AM on September 20, a man was presumed drowned in Lake Catouatchie, southwest of New Orleans.[25] The man had been shrimping in the lake in choppy waters caused by the storm, and dove into the water without a life vest to untangle a net from his boat's propeller. After he freed the propeller, the boat was carried away by the current in the lake, and he was last seen swimming after the boat. After the disappearance, the Coast Guard launched a search with rescue boats and search dogs but could not locate him.[26] His body was eventually found on the morning of September 22.[27] Captain Pat Yoes, of the St. Charles Parish Sheriff's Office, said that the storm "obviously ... played a part" in the man's death,[26] but Lieutenant Commander William Brewer of the United States Coast Guard told the press that he did not "think it was directly storm-related."[25]

Hermine spawned two tornadoes in Mississippi. One destroyed two mobile homes, damaged seven cars, and resulted in one minor injury;[28] the other caused only minor damage. Rainfall of 4 to 5 inches (100 to 130 mm) caused localized flooding; in southern Walthall County, parts of Mississippi Highway 27 were under 1 foot (0.30 m) of water.[29] Over 6 inches (150 mm) of rainfall was reported in Alabama, resulting in the flooding of apartments and several roads and the closure of several highways. Numerous cars were damaged, and motorists were stranded on Bibb County Route 24.[30] Floodwaters also covered U.S. Route 11 near Tuscaloosa, Alabama stranding several motorists and a milk truck.[31] Flash flood warnings were issued in Bibb and Shelby counties as northern Alabama experienced its first rainfall in the month of September.[32] The rainfall extended eastward into Georgia, where the rains led the state to lift a fire alert for three northern counties,[19][33] South Carolina and North Carolina.[34] The remnants of the storm dumped 10.5 inches (27 cm) of rain on Charleston, South Carolina and rainfall of up to one foot was reported in other parts of the state. The rain in Charleston led to over five feet of standing water in some neighborhoods, forcing several families to evacuate their mobile homes and stranding a number of vehicles. As a result, the local police closed several roads, including sections of Interstate 526.[35]

Overall, damage totaled $85,000 (1998 USD);[36] the effects were described as minor.[37] Although the effects from Hermine were small, counties in Louisiana and Texas were declared disaster areas due to damage associated with the earlier Tropical Storm Frances and the Louisiana Office of Emergency Preparedness extended these funds to cover damages from Hermine as well.[38]

Aftermath

The heavy rains from Hermine combined with those from Frances caused major fish kills in southern Louisiana, the first since those caused by Hurricane Andrew in 1992. The rain from the two storms flooded the swamps in south Louisiana, where it rapidly lost oxygen due to decaying plant matter. After the swamps began to drain, the low-oxygen water flowed into streams, canals, and bayous in the area, and testing in the days following the storm showed that the water was "almost devoid of oxygen." Without sufficient oxygen, local fish population died quickly, filling waterways, particularly in the area of Lake Charles and Lafayette, according to the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries.[39] In total, the fish kills affected at least a dozen separate lakes and bayous in the state.[40]

The combined effects of Hermine and other storms caused significant damage to Louisiana agriculture. The standing water after Hermine provided ideal hatching conditions for mosquitoes, who formed swarms large enough to kill livestock in the days after the storm. At least twelve bulls and horses were killed by mosquito bites in the next week, including bulls who drowned after wading into deep water to escape the insects. The rains and standing water from the storm also prevented farmers from drying out soybeans for harvest and ruined sugar cane. According to Louisiana Agriculture Commissioner Bob Odom, the combined effects of Hurricane Earl, Tropical Storm Frances, and Tropical Storm Hermine caused $420 million in direct and indirect losses for Louisiana farmers.[41]

See also

- Other storms of the same name

- Hurricane Georges

- List of Florida hurricanes

- List of North Carolina hurricanes (1980–99)

Notes

- Hermine did not directly cause any direct fatalities; however, it may have contributed to two deaths, in Florida and Louisiana.

References

- Lixion A. Avila (November 9, 1998). Tropical Storm Hermine Tropical Cyclone Report (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on October 6, 2010. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- Gary Padgett (1998). Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary; September, 1998 (Report). Australiansevereweather.com. Retrieved 2008-12-13.

- Lixion A. Avila (September 17, 1998). Tropical Depression Eight Discussion Number 1 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- Edward N. Rappaport (September 17, 1998). Tropical Depression Eight Discussion Number 2 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- Lixion A. Avila (September 18, 1998). Tropical Depression Eight Discussion Number 4 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- Lixion A. Avila (September 18, 1998). Tropical Depression Eight Discussion Number 5 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- James M. Gross (September 19, 1998). Tropical Depression Eight Discussion Number 7 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- Richard J. Pasch (September 19, 1998). Tropical Storm Hermine Discussion Number 9 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- Edward N. Rappaport (September 19, 1998). Tropical Storm Hermine Discussion Number 10 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- Bruce Sullivan (September 20, 1998). Storm Summary 13 for Tropical Depression Hermine (Report). Weather Prediction Center. Archived from the original on 2008-10-04. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- Edward N. Rappaport (September 23, 1998). Tropical Depression Eleven Discussion Number 1 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-12-09.

- "Grand Isle Abandoned - The approaching storm chases residents of Louisiana's low-lying areas to the mainland". Dayton Daily News. September 20, 1998. p. 12A.

- "Tropical storm forces third evacuation". Sunday Gazette-Mail. Associated Press. September 20, 1998. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved 2008-11-19.

- "LA. Prepares for Another Tropical Storm". United Press International. September 19, 1998. Retrieved 2008-11-19.

- Bacon-Blood, Littice (September 20, 1998). "Tropical Storm Hermine Soaks Storm-weary Coast - Grand Isle Evacuates Third Time". The Times-Picayune. p. A1.

- "Louisiana braces for third storm Oil workers evacuated as heavy rains hit coast". The Dallas Morning News. Associated Press. September 19, 1998. Retrieved 2008-11-19.

- "Oil, natural gas futures retreat after storm fails to pack a wallop". Associated Press. September 21, 1998. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved 2008-11-19.

- "Coastal Areas Calm After Hermine". United Press International. September 20, 1998. Retrieved 2008-11-19.

- David Roth. "Tropical Storm Hermine - September 13–23, 1998". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved 2008-12-11.

- "Tropical storm remnants spread through South". Associated Press. September 20, 1998. Retrieved 2008-12-11.

- Youngblood, Garrett (September 20, 1998). "Hermine Sends Rains Our Way - Storm Knocks Tree Down, Causes Traffic Accidents". Orlando Sentinel. p. B1.

- "Tropical Storm Event Report for Louisiana". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on 2012-08-06. Retrieved 2008-12-11.

- "Hermine barely attained storm status". USA Today. June 11, 1999. Retrieved 2009-01-01.

- Mary Ann Burke; et al. (1999). "Mariners Weather Log" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2009-01-01.

- Delguzzi, Kristen (September 21, 1998). "Georges Raises Fears as Hermine Fizzles". The Times-Picayune. p. A1.

- Bell, Rhonda (September 22, 1998). "Search for Man in Lake Still On - Officials Say Drowning Likely". The Times-Picayune. p. B1.

- "Westwego Man's Body Found After Drowning". The Times-Picayune. September 24, 1998. p. B2.

- "Remnants Produce Heavy Rains". The Sun Herald. Biloxi, MS. September 21, 1998. p. A9.

- "Tropical Storm Event Report for Mississippi". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on 2012-08-06. Retrieved 2008-12-11.

- "Flash Flood Event Report for Alabama". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on 2012-08-05. Retrieved 2008-12-11.

- "Hermine Leaves Memento". The Florida Times-Union. September 22, 1998. p. A3.

- Sikora, Frank (September 22, 1998). "Storm's Remains Flood Parts of State". Birmingham News. p. 1B.

- "Abducted Toddler Could be in Area". The Augusta Chronicle. September 22, 1998. p. C9.

- Roth, David M; Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall in the Southeastern United States". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Point Maxima. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- Reilly, Brenna; Wise, Warren (September 22, 1998). "Roads, homes flooded RECORD RAINFALL: Heavy storms left 10.5 inches of rain at Charleston International Airport by 11:45 p.m., according to the National Weather Service". The Post and Courier. Charleston, SC. p. 1.

- Richard Pasch; et al. (2001). "Atlantic Hurricane Season of 1998" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-05-07. Retrieved 2008-12-13.

- "Conditions for the month of September 1998". United States Geological Survey. June 8, 2007. Retrieved 2008-12-22.

- "Foster asks Clinton for Disaster Declaration". The Times-Picayune. September 22, 1998. p. A4.

- Anderson, Bob (September 26, 1998). "Tropical storm causes fish kill". The Advocate. Baton Rouge. p. 4A.

- "Tangipahoa Leaders Eye Contingency Plans". The Advocate. Baton Rouge. September 25, 1998. p. 4A.

- Tahan, Raya (September 28, 1998). "Farm Scene: Mosquitos are killing livestock in Louisiana". Associated Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tropical Storm Hermine (1998). |