Hubert de Burgh, 1st Earl of Kent

Hubert de Burgh, 1st Earl of Kent (c. 1170 – before 5 May 1243) was an English nobleman who served as Justiciar of England and Ireland during the reigns of King John (1199–1216) and of his infant son and successor King Henry III (1216–1272). During his service, he was one of the most influential and powerful men in English politics.

Hubert de Burgh | |

|---|---|

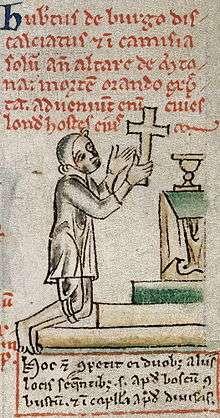

Hubert de Burgh seeking sanctuary in 1234, by Matthew Paris, from his Historia Anglorum | |

| Chief Justiciar of England | |

| In office 1215–1232 | |

| Monarch | John Henry III |

| Preceded by | Peter des Roches |

| Succeeded by | Stephen de Segrave |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1170 |

| Died | before 5 May 1243 Banstead, England |

| Nationality | English |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | John Hubert Margaret |

| Occupation | Earl of Kent |

Origins

De Burgh's family were minor landholders in Norfolk and Suffolk, from whom he inherited at least four manors.[1] His mother was named Alice, and his father may have been named Walter.[1] He was the younger brother of William de Burgh (d. 1206),[2] the founder of the de Burgh/Burke/Bourke dynasty in Ireland. His younger brother Geoffrey was Archdeacon of Norwich and then Bishop of Ely, and his younger brother Thomas was castellan of Norwich.[1]

Appointments by King John

De Burgh entered the service of Prince John by 1198, and from then until 1202 rose in importance in John's administration. He served successively as chamberlain of John's household, an ambassador to Portugal, sheriff first of Dorset and Somerset and then of Berkshire and Cornwall, custodian of the castles of Dover, Launceston and Windsor, and then custodian of the Welsh Marches.[1] For these services, he was granted a series of manors, baronies, and other castles, and became a powerful figure in John's administration.[1]

In 1202, de Burgh was sent to France by King John, to assist in the defense of Poitou against King Philip II of France. De Burgh was appointed castellan of the great castle of Chinon in Touraine. During this time, he served as guard of the captured Arthur I, Duke of Brittany. After almost all of Poitou had fallen to the French king, de Burgh held the castle for an entire year, until he was captured during the ultimately successful storming of the castle in 1205.[1] He was held captive until 1207, during which time his royal appointments and grants of land passed to other men. Following his return to England, de Burgh did however acquire fresh offices in John's administration. He also acquired lands scattered throughout East Anglia, the southwest of England, and elsewhere, making him once again an important baron in England.[1]

In 1212, de Burgh returned to France at first as deputy seneschal of Poitou and then as seneschal. He served John in his efforts to recover dominions lost to Philip II of France, until the signing of a truce between John and Philip following John's failed military campaign in France in 1214.[1]

Chief Justiciar

De Burgh remained loyal to King John during the barons' rebellion in the last years of his reign. In the early stages of that rebellion, John sent de Burgh to London with the Bishop of Coventry, in an unsuccessful attempt to command the people of London to resist the Barons' military advance. De Burgh and Philip d'Aubigny brought together the king's troops at Rochester, but then John made peace with the rebels. In Magna Carta, of 1215, de Burgh is listed as one of those who advised the king to sign that charter, of which his brother Geoffrey de Burgh, Bishop of Ely, was a witness. De Burgh is also listed as the person who would act on the king's behalf if the king were out of the country. Soon after the issuing of Magna Carta, de Burgh was officially declared Chief Justiciar of England.[3]

During the First Barons' War of 1215–1217, de Burgh served John as sheriff of Kent and Surrey, as well as castellan of Canterbury and Dover. De Burgh defended Dover Castle during a siege that lasted until John died in October, 1216, and the infant King Henry III (1216-1272) was crowned. On 24 August 1217, a French fleet arrived off the coast of Sandwich in Kent, in order to provide Prince (later King) Louis of France, then ravaging England, with soldiers, siege engines and fresh supplies.[4][5] Hubert set sail to intercept the French fleet and at the resulting Battle of Sandwich[6] he scattered the French and captured their flagship The Great Ship of Bayonne, commanded by Eustace the Monk, who was promptly executed.[6] When the news reached Louis, he entered into fresh peace negotiations.[6]

Regent to Henry III

When Henry III came of age in 1227 de Burgh was made Governor of Rochester Castle, lord of Montgomery Castle in the Welsh Marches and Earl of Kent. He remained one of the most influential people at court. On 27 April 1228 he was named Justiciar for life.[3] But in 1232 the plots of his enemies finally succeeded and he was removed from office and soon was in prison. He escaped from Devizes Castle and joined the rebellion of Richard Marshal, 3rd Earl of Pembroke, in 1233. In 1234, Edmund Rich, Archbishop of Canterbury, effected a reconciliation. He officially resigned the Justiciarship about 28 May 1234, but no longer exercised the power of the office after September 1232.[3] The judgment was reversed by William Raleigh also known as William de Raley in 1234, which, for a time, restored the earldom.[7]

Trouble with the King

The marriage of Hubert de Burgh's daughter Margaret (or Megotta as she was also known) to Richard of Clare, the young Earl of Gloucester, brought de Burgh into some trouble in 1236, for the earl was as yet a minor and in the king's wardship, and the marriage had been celebrated without the royal licence. Hubert, however, protested that the match was not of his making, and promised to pay the king some money, so the matter passed by for the time. Eventually the marriage came to an end, by way of her death.[8][9][10]

Lands acquired

In 1206 he purchased the manor of Tunstall in Kent from Robert de Arsic.[11] His eldest son John de Burgh[12] later inherited Tunstall.[11]

He was appointed Constable of Dover Castle and was also given charge of Falaise, in Normandy. At Falaise he was the gaoler of Arthur I, Duke of Brittany, the nephew of King John and boy claimant to the English throne. Arthur may or may not have been murdered after leaving de Burgh's custody; his fate is unknown.

De Burgh is cited as having been appointed at some time before 1215 Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, which position later, after the Baron's War, carried with it ex officio the Constableship of Dover Castle. In the case of de Burgh however, a rather long period seems to have elapsed between the two appointments.[13]

Sometime after 1215, De Burgh started building a castle in Hadleigh having been rewarded the land by King John.[14] The licence to crenellate was retrospectively given in 1230, at which point that original castle had been completed.[14] After falling out with King Henry III, De Burgh was stripped of Hadleigh Castle.[14] The castle went claimed by the monarchy and stayed in royal hands until being sold off in 1551.[15] Much of the stonework was dismantled and sold off. What remained of the ruin later suffered from several landslips. The remains of the castle are owned by English Heritage and can be visited.[15]

Marriages

Hubert was initially betrothed to Joan de Redvers, a daughter of William de Redvers, 5th Earl of Devon (died 1217), but the marriage never took place and she went on to marry William II Brewer (d.1232), eldest surviving son and heir of William Brewer (died 1226) a prominent administrator and judge in England during the reigns of Kings Richard I, his brother King John, and the latter's son Henry III.

De Burgh married three times:

- Firstly to Beatrice de Warrenne, daughter of William de Warrenne, with sons Sir John, whose descendant Margaret married Richard Óg de Burgh, 2nd Earl of Ulster, and Sir Hubert, ancestor of Thomas Burgh of Gainsborough.

- Secondly in September 1217[16] to Isabella, Countess of Gloucester, daughter and heiress of William Fitz Robert, 2nd Earl of Gloucester.

- Thirdly to Princess Margaret, sister of King Alexander II of Scotland;[17] their daughter Margaret married Richard de Clare, 6th Earl of Gloucester.

Death

Hubert de Burgh died in 1243 in Banstead in Surrey,[11] and was buried in the Church of the Friars Preachers (commonly called Black Friars) in Holborn, London.[8]

Fictional portrayals

Hubert is a character in the play King John by William Shakespeare. On screen he has been portrayed by Franklyn McLeay in the silent short King John (1899), which recreates John's death scene at the end of the Shakespeare play, by Jonathan Adams in the BBC TV drama series The Devil's Crown (1978), and by John Thaw in the BBC Shakespeare version of The Life and Death of King John (1984). The story of his daughter's marriage is told in the novel The Marriage of Meggotta (1979) by Edith Pargeter.[18]

References

- West 2004

- Almond's peerage of Ireland 1767 p.6 Earls of Clanricarde

- Powicke Handbook of British Chronology p. 70

- Carpenter 1990, pp. 43–44

- Ridgeway 2004

- Carpenter 1990, p. 44

- Plucknett, T., A Concise History of the Common Law, Little, Brown and Co. 1956, p. 170

- Stephen, Leslie, ed. (1886). "Burgh, Hubert de". Dictionary of National Biography 7. (London: Smith, Elder & Co.), p. 321

- Thomas Andrew Archer. Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Volume 10 "Clare, Richard de (1222-1262)" p. 393

- Tewkesbury Annals p. 106 ; Pat. Rolls, 17 b

- Hasted, Edward (1798). "Parishes". The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent. Institute of Historical Research. 6: 80–98. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- Name Latinised to de Burgo

- White and Black books of the Cinque Ports, Vol XIX, 1966

- Alexander, Magnus; Westlake, Susan (January 2009). Hadleigh Castle Essex, Earthwork Analysis. Survey Report (PDF) (Technical report). English Heritage. p. 9. eISSN 1749-8775. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- Alexander, Magnus; Westlake, Susan (January 2009). Hadleigh Castle Essex, Earthwork Analysis. Survey Report (PDF) (Technical report). English Heritage. p. 19. eISSN 1749-8775. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- Robert B. Patterson, ‘Isabella, suo jure countess of Gloucester (c.1160–1217)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, September 2004; online edn, October 2005 accessed 24 November 2006

- Stephen, Leslie, ed. (1886). "Burgh, Hubert de". Dictionary of National Biography 7. (London: Smith, Elder & Co.), p. 317

- Margaret Lewis (1994). Edith Pargeter--Ellis Peters. Seren. ISBN 978-1-85411-128-9.

Bibliography

- Burke, Eamon "Burke People and Places", Dublin, 1995.

- Carpenter, D. A. "The Fall of Hubert De Burgh", Journal of British Studies, vol. 19 (1980)

- Carpenter, D. A. (1990). The Minority of Henry III. Berkeley, US and Los Angeles, US: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07239-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Ellis, C. Hubert de Burgh, A Study in Constancy (1952)

- Harwood, Brian, "Fixer & Fighter The Life of Hubert de Burgh, Earl of Kent, 1170 - 1243. Published by Pen & Sword (2016)

- Hunt, William (1886). . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 7. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Johnston, S.H.F. "The Lands of Hubert de Burgh", English Historical Review, vol. 50 (1935)

- Powicke, F. Maurice and E. B. Fryde Handbook of British Chronology 2nd. ed. London:Royal Historical Society 1961

- Remfry, P.M., Grosmont Castle and the families of Fitz Osbern, Ballon, Fitz Count, Burgh and Braose (ISBN 1-899376-56-9)

- Ridgeway, H. W. (2004). "Henry III (1207–1272)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/12950. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Weiss, Michael "The Castellan: The Early Career of Hubert de Burgh", Viator, vol. 5 (1974)

- West, F. J. (2004). "Hubert de Burgh". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/3991. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)