Cinque Ports

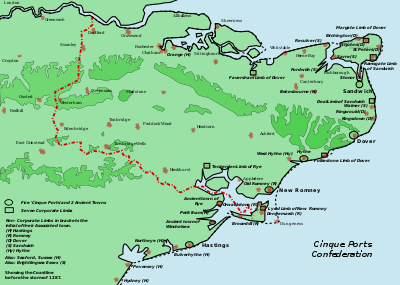

The Confederation of Cinque Ports (/sɪŋk pɔːrts/)[1] is a historic series of coastal towns in Kent, Sussex and Essex.[2] It was originally formed for military and trade purposes, but is now entirely ceremonial. The ports lie at the eastern end of the English Channel, where the crossing to the continent is narrowest. The name is Norman French, meaning "five ports". They were:

Rye, originally a subsidiary of New Romney, was raised as one of the Cinque Ports after New Romney was damaged by the severe 1287 storm; its harbour silted up, and the River Rother shifted course closer to Rye. As a result, New Romney rapidly lost importance in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

Other towns also contribute to the confederation, including two 'ancient towns', and seven 'limbs'.

Ancient Towns

The five ports are supported by the two so-called Ancient Towns of Rye and Winchelsea,[2] whose councils traditionally maintained defence contingents for the realm of England.

Limbs

Apart from the five ports and the two Ancient Towns, there are seven other members of the Confederation, which are considered to be Limbs of the other towns. These are:

Connected towns

There are in addition some 23 towns, villages and offices that have varying degrees of connection to the ancient Liberties of the Cinque Ports. They are expressly mentioned in the Magna Carta of 1297 (clause 9).

The coastal confederation during its mediaeval period consisted of a confederation of 42 towns and villages in all. These include:

- Limbs of Hastings – Grange (now part of Gillingham, Kent), Bekesbourne, Bulverhythe, Northeye (former village in Sussex[4]), Eastbourne, Hydney (now Hampden Park, part of Eastbourne), Pebsham (small village between Bulverhythe and Bexhill-on-Sea [then as Bexhill]), Pevensey and Seaford (in Sussex)

- Limbs of Sandwich – Reculver, Sarre, Fordwich, Walmer, Stonar (near Richborough), and Brightlingsea (in Essex).[5] Brightlingsea, is the only town north of the Thames Estuary in the confederation.[6]

- Limbs of Dover – Birchington, St. Johns (part of Margate), St. Peters, Ringwould, Woodchurch and Kingsdown

- Limbs of Hythe – West Hythe[7]

- Walmer, Ramsgate

History of the ports

Formation, duties and privileges

The origins of the Cinque Ports can be traced back to Anglo-Saxon times,[8] when certain south-east ports were granted the local profits of justice in return for providing ships.[9] By 1100, the term Cinque Ports had come into use; and in 1155 a Royal Charter established the ports to maintain ships ready for The Crown in case of need. The chief obligation laid upon the ports, as a corporate duty, was to provide 57 ships for 15 days' service to the king annually, each port fulfilling a proportion of the whole duty.[10] In return the towns received the following privileges:

Exemption from tax and tallage, right of soc and sac, tol and team, blodwit (the right to punish shedders of blood) and fledwit (the right to punish those who were seized in an attempt to escape from justice), pillory and tumbril, infangentheof and outfangentheof, mundbryce (the breaking into or violation of a man's mund or property in order to erect banks or dikes as a defence against the sea), waifs and strays, flotsam and jetsam and ligan

That is to say:

Exemption from tax and tolls; self-government; permission to levy tolls, punish those who shed blood or flee justice, punish minor offences, detain and execute criminals both inside and outside the port's jurisdiction, and punish breaches of the peace; and possession of lost goods that remain unclaimed after a year, goods thrown overboard, and floating wreckage.

The leeway given to the Cinque Ports, and the turning of a blind eye to misbehaviour, led to smuggling, though common everywhere at this time becoming more or less one of the dominant industries.

A significant factor in the need to maintain the authority of the Cinque Ports by the King was the development of the Royal Navy. King Edward I of England granted the citizens of the Cinque Ports special privileges, including the right to bring goods into the country without paying import duties; in return the Ports would supply him with men and ships in time of war (as in the Welsh campaign of 1282).[11] The associated ports, known as "limbs", were given the same privileges. The five head ports and two ancient towns were entitled to send two Members to Parliament. A Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports was appointed, and also held the title of Constable of Dover Castle, and whilst this office exists today, it is now a purely honorary title, with an official residence at Walmer Castle. The town of Hastings was the head port of the Cinque Ports in mediaeval times. The towns also had their own system of courts.

Barons

All Freemen of the ports, termed "portsmen", were deemed in the age of Feudalism to be barons, and thus members of the baronage entitled to attend the king's parliament - a privilege granted in 1322 in recognition of their earlier support of the Despensers, father and son.[12] Termed "Barons of the Cinque Ports", they reflected an early concept that military service at sea constituted land tenure per baroniam making them quasi feudal barons. The early-14th-century treatise Modus Tenendi Parliamentum stated the Barons of the Cinque Ports to hold a place of precedence below the lay magnates (Lords Temporal) but above the representatives of the shires and boroughs (Knights of the Shire and burgesses). During the deposition of Edward II, the chronicles made a specific point of noting the presence of the Barons in the embassy of deposition - "praecipue de portubus...barones des Portez" ('especially the [Cinque] Ports...the barones of the Ports').[13] Writs of summons to parliament were sent to the warden following which representative barons of the Cinque Ports were selected to attend parliament. Thus the warden's duty in this respect was similar to that of the sheriff who received the writs for distribution to the barons in the shires. The existence of common (i.e. communal) seals of the barons of the individual ports (see illustration) suggests they formed a corporation as the seal was designed to be affixed to charters and legal documents which would bind them as a single body.[14] This no doubt related to their privileges as monopolies. The warden and barons often experienced clashes of jurisdiction.[10]

In the 21st century the title "Baron of the Cinque Ports" is now reserved for Freemen elected by the Mayor, Jurats and Common Council of the Ports to attend a coronation and is solely honorary in nature. "Since time immemorial", the barons had held the right to hold a canopy above the monarch during the procession on foot between Westminster Hall and Westminster Abbey. This procession was discontinued after the Coronation of George IV in 1821, but for the Coronation of Edward VII in 1902 the barons were found a new role. They were to process inside the abbey as far as the choir and there receive the banners of the monarch's realms, a function which they have repeated at every coronation since.[15]

Changes in composition

As time went by and some ports declined or silted up, others were added. Rye and Winchelsea were attached to Hastings as "Ancient Towns" in the 12th century, and later became members in their own right. The following "corporate limbs" were added in the 15th century: Lydd, Faversham, Folkestone, Deal, Tenterden, Margate and Ramsgate. Other places associated with the Cinque Ports and sometimes described as "non-corporate limbs" included Bekesbourne, Birchington, Brightlingsea, Fordwich, Pevensey, Reculver, Seaford, Stonor and Walmer.[2] At one time there were 23 limbs.

Decline

The continuing decline of the confederation of the Cinque Ports may be ascribed to a variety of different circumstances. While they survived the raids from the Danes and the French, the numerous destructive impact of plagues, and the politics of the 13th-century Plantagenets and the subsequent War of the Roses, natural causes such as the silting of harbours and the withdrawal of the sea did much to undermine them.[16] The rise of Southampton, and the need for larger ships than could be crewed by the 21-man service of the ports, also contributed to the decline.

Although by the 14th century the confederation faced wider challenges from a greater consolidation of national identity in the monarchy and Parliament, the legacy of the Saxon authority remained. Even after the 15th century, the Ancient Towns continued to serve with the supply of transport ships.

During the 15th century, New Romney, once a port of great importance at the mouth of the river Rother (until it became completely blocked by the shifting of sands during the South England flood of February 1287), was considered the central port in the confederation, and the place of assembly for the Cinque Port Courts, the oldest such authority being vested in the "Kynges high courte of Shepway", which was being held from at least 1150. It was here that from 1433 the White (1433–1571) and Black (1572–1955) Books of the Cinque Port Courts were kept.

Much of Hastings was washed away by the sea in the 13th century. During a naval campaign of 1339, and again in 1377, the town was raided and burnt by the French, and went into a decline during which it ceased to be a major port. It had no natural sheltered harbour. Attempts were made to build a stone harbour during the reign of Elizabeth I, but the foundations were destroyed by the sea in storms.

New Romney is now about a mile and a half from the seafront. It was originally a harbour town at the mouth of the River Rother. The Rother estuary was always difficult to navigate, with many shallow channels and sandbanks. In the latter part of the thirteenth century a series of severe storms weakened the coastal defences of Romney Marsh, and the South England flood of February 1287 almost destroyed the town. The harbour and town were filled with sand, silt, mud and debris, and the River Rother changed course, now running out into the sea near Rye, Sussex. New Romney ceased to be a port.

Hythe is still on the coast. However, although it is beside a broad bay, its natural harbour has been removed by centuries of silting.

Dover is still a major port.

Sandwich is now 3 km (1.9 mi) from the sea and no longer a port.

Ongoing changes in the coastline along the south east coast, from the Thames estuary to Hastings and the Isle of Wight inevitably reduced the significance of a number of the Cinque port towns as port authorities. However, ship building and repair, fishing, piloting, off shore rescue and sometimes even "wrecking" continued to play a large part in the activities of the local community.

By the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, the Cinque Ports had effectively ceased to be of any real significance, and were absorbed into the general administration of the Realm. Queen Elizabeth I sanctioned the first national lottery that was held in 1569 in an effort to raise funds for the crumbling Cinque Ports.[17] With the advance in shipbuilding techniques came a growth in towns such as Bristol and Liverpool and the wider development of ports such as London, Gravesend, Southampton, Chichester, Plymouth and the royal dockyards of Chatham, Portsmouth, Greenwich, Woolwich and Deptford. A further reason for the decline of many older ports may be ascribed to the development of the railway network across Britain, and the increased quantity of overseas trade it could distribute from the new major ports developing from the 18th century.

Local Government reforms and Acts of Parliament passed during the 19th and 20th centuries (notably the Great Reform Act of 1832) have eroded the administrative and judicial powers of the Confederation of the Cinque Ports, when New Romney and Winchelsea were disenfranchised from the Parliament, with representation provided through their Counties alone, while Hythe and Rye's representation was halved.

In 1985, HMS Illustrious established an affiliation with the Cinque Ports. In 2005, the affiliation was changed to HMS Kent.

Heraldry

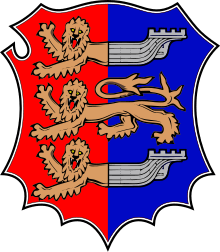

The distinctive heraldic emblem of the Cinque Ports is the front half of a lion joined to the back of a ship, seen in the coats of arms of several towns, and also in the heraldic banner (flag) of the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports. This was originally created by heraldic dimidiation.[18]

Cinque Ports Acts 1811 to 1872

The Cinque Ports Acts 1811 to 1872 is the collective title of the following Acts:[19]

- The Cinque Ports Act 1811 (51 Geo 3 c 36)

- The Cinque Ports Act 1821 (1 & 2 Geo 4 c 76)

- The Cinque Ports Act 1828 (9 Geo 4 c 37)

- The Pilotage Law Amendment Act 1853 (16 & 17 Vict c 129)

- The Cinque Ports Act 1855 (18 & 19 Vict c 48)

- The Cinque Ports Act 1857 (20 & 21 Vict c 1)

- The Cinque Ports Act 1869 (32 & 33 Vict c 53)

- The Merchant Shipping Act 1872 (35 & 36 Vict c 73 s 10)

References

- Collins English Dictionary (3rd ed.)

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 377–379.

- History of the Cinque Ports: Cinque Port Limbs

- Site of the Medieval Village of Northeye (C) Simon Carey :: Geograph Britain and Ireland. Geograph.org.uk. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

- Hasted, Edward (1800). "Parishes". The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent. Institute of Historical Research. 10: 152–216. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- "The Cinque Port Obligations & Ship Money". open-sandwich.co.uk. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- Cinque Ports 1155 to 1500 – VillageNet History – History effecting Kent & Sussex. Villagenet.co.uk (15 May 2012). Retrieved 2013-07-17.

- G. O. Sayles, The Medieval Foundations of England (London 1967) p. 186

- S. H. Steinberg ed. A New Dictionary of British History (London 1963) p. 71

- Roskell, J.S. History of Parliament, House of Commons 1386–1421, Stroud, 1992, vol.1, p. 751, Cinque Ports

- J R Tanner ed., The Cambridge Medieval History (Cambridge 1932) p. 517

- D. Jones, The Plantagenets (London 2012) p. 402

- J G Edwards ed., Historical Essays in Honour of James Tait (Mancheste 1933) p. 38 and 45

- Sigillum commune baronum, from mediaeval Latin baro, baronis (m), thus baronum is "of the barons"

- Strong, Sir Roy (2005). Coronation: A History of Kingship and the British Monarchy. London: Harper Collins. p. 474. ISBN 978-0-00-716054-9.

- S. Steinberg, A New Dictionary of British History (London 1963) p. 72

- Moore, Peter G. (1997). "The Development of the UK National Lottery: 1992-96". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series A (Statistics in Society). 160 (2): 169–185. doi:10.1111/1467-985X.00055.

- Arthur Charles Fox-Davies, A Complete Guide to Heraldry, 1909, pp. 182, 525. Further reading see: Geoffrey Williams, Heraldry of the Cinque Ports, 1971

- The Short Titles Act 1896, section 2(1) and Schedule 2

Other sources

- Burrows, Montagu. Cinque Ports. London And New York, Longmans, Green, and Co, 1888.

- Ford, Ford Madox. The Cinque Ports : a historical and descriptive record. Edinburgh ; London : W. Blackwood and Sons. 1900.

- Hinings, Edward. The Cinque Ports: History People and Places[1]

- Jessup, Ronald Frederick. The Cinque Ports. (2nd ed.) London, New York, Batsford, 1952.

- Murray, K. M. Elizabeth. The constitutional history of the Cinque ports. Manchester, Manchester University Press, 1935.