Houseplant

A houseplant is a plant that is grown indoors in places such as residences and offices, namely for decorative purposes, but studies have also shown them to have positive psychological effects and as well as help with indoor air purification, since some species, and the soil-dwelling microbes associated with them, reduce indoor air pollution by absorbing volatile organic compounds including benzene, formaldehyde, and trichloroethylene. While generally toxic to humans, such pollutants are absorbed by the plant and its soil-dwelling microbes without harm.[1]

Common houseplants are usually tropical or semi-tropical epiphytes, succulents or cacti.[2] Houseplants need the correct moisture, light levels, soil mixture, temperature, and humidity. As well, houseplants need the proper fertilizer and correct-sized pots.

Cultural history

Early history

Ancient Egyptians and Sumerians grew ornamental and fruiting plants in decorative containers. Ancient Greeks and the Romans cultivated laurel trees in earthenware vessels. In ancient China, potted plants were shown at garden exhibitions over 2,500 years ago. In the middle ages, ornamental gardening was restricted to monasteries.[3]

In kitchen gardens of the medieval era, vegetable plants such as fennel, cabbage, onion, garlic, leeks, radishes and parnips, peas, lentils and beans were grown if there was space for them. Gillyflowers were also displayed in containers.[4]

15th–18th century

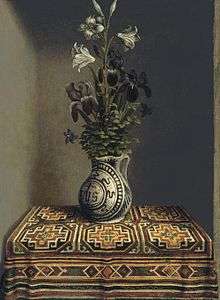

In the Renaissance, plant collectors and affluent merchants from Italy, the Netherlands and Belgium imported plants from Asia Minor and the East Indies. Senecio angulatus was introduced in Malta and the rest of Europe in the 15th century as an ornamental plant.[5] In the 16th century, fascination in exotic plants grew among the aristocracy of France and England, with inventor and writer Sir Hugh Platt publishing Garden of Eden in 1660, which was a book about how to grow plants in homes.[3]

Up to the 17th century, there was little evidence of the culture of houseplants for Central Europe. One explanation is the low standard of living at that time. Using the window sill in the living room as a plant shelter meant less light, freedom of storage and freedom of movement. Even in the often dark and unheated side rooms, there were almost no plants.[6]

Plant breeding developed in the late 17th and 18th centuries. Now plants were widely cultivated with the researchers and botanists brought over 5,000 species to Europe from their ship expeditions from South America, Africa, Asia and Australia.[3] These innovations were drawn and presented in the botanical gardens and in private court collections. At the beginning of the bourgeois age at the end of the 18th century, flower tables became part of the salons. Furthermore, nurseries were flourishing in the 18th century, which stocked thousands of plants, including citrus, jasmines, mignonette, bays, myrtles, agaves and aloes.[7]

19th century–early 20th century

The dark and smoky Victorian era saw the first use of houseplants by the middle class, which were perceived as a symbol of social status and moral value, and were used on windows, in Wardian cases, trellises and stands.[8] Exotic and hardy foliage plants became popular as they tolerated the typical gloomy and snug environment inside a Victorian house.[9] Popular plants in that era included palms (kentia palms and parlour palms), maidenhair ferns, geraniums, ferns and aspidistras that were often placed on window ledges and in drawing rooms.[7]

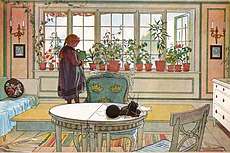

At the end of the 19th century, the range already included begonias, orchids, cineraria, clivia, cyclamen and flamingo flowers, but also leafy ornamental plants such as ferns, silver fir, ornamental asparagus, lilium, snake plant, English Ivy and rubber tree.[3] In the early 20th century, large often floor-to-ceiling windows ensured a seamless transition from the interior to the garden and architectural reforms and the development of new processes for glass production ensured that larger windows were used and thus improved lighting in the living rooms. Senecio angulatus gained popularity following the Boer War in Queensland in the Edwardian era, where it was displayed in garden pillars in Brisbane newspapers in the late 1900s.[10]

In the early 20th century, houseplants became dated due to their cluttered popularity in the Victoria, though the golden pothos, Chinese evergreens, peperomia obtusifolia, Boston ferns, cactus and ficus elastica had a modest presence throughout the first half of the century, but more so after World War II when houseplants became mainstream again.[7]

1950s–present

Golden Pothos, monsteras, African Violets and Swedish Ivy gained popularity in the 1950s and 1960s, when the plant fad returned again after WWII. In the 1960s, there was an introduction of plant care labels. Garden centers became ubiquitous in the 1970s and homes often had foliage-heavy plants in an "indoor jungle" backdrop. Plants were highly fashionable in the 1970s and they included, philodendrons, string of hearts, Boston ferns, umbrella trees, syngoniums, tradescantias (wandering jews), kentia palms, Tahitian brides, spider plants, weeping figs, Ficus lyrata, Ficus elastica, dracaenas, aglaonemas, aluminium plants, and snake plants, which were a common sight in homes in that decade.[12][13]

In the 1980s, the lush tone started to diminish in living rooms where it was fashionable to have only one or two grand botanical plants, such as a ficus or yucca. Shopping malls, however, still remained decorated with lush plants. In the 1990s, moth orchids became trendy, as well as the Dracaena fragrans and golden pothos, which still remained stylish. The 1990s also brought a wave of interest in artificial plants. In the 2000s, Lucky bamboos became popular and sought for plants.[14]

The mid-late 2010s and 2020s were revivalist decades with fashionable plants from earlier decades (listed above) being revitalised and popularised by social media (especially Instagram). Popular houseplants in these two decades include, peace lilies, prayer plants, ZZ plants, begonias, swiss cheese plants, crotons, peperomias, pileas, air plants, hypoestes, cacti, Boston fern, and many succulent plants (such as curio or senecios, euphorbias, sedums, schlumbergeras, hoyas, etc).[15]

The origin of houseplants

Most houseplants are tropical evergreen species that adapted to survive in a tropical climate which ranges from 15 °C to 25 °C (60 °F to 80 °F) year-round. The natural range of plant species, the varieties of which are used as houseplants, allows important conclusions to be drawn about their husbandry requirements. Plants from tropical rainforests do not need to rest, unlike those from temperate zones. As a rule, their humidity requirements are particularly high. A more precise knowledge of the natural vegetation area of a plant is therefore helpful in maintenance.

- Tropical Rainforest

The majority of the plant species kept as houseplants come from the area of the tropical rainforest and the adjacent areas. The length of the day is constantly around twelve hours. Precipitation is evenly distributed over the year. The average daily temperature depends on the respective altitude. In tropical forests that are not at altitudes above 600 meters, it is usually evenly between 24 and 28 degrees Celsius all year round. In higher-lying rainforests, the so-called tropical mountain forest, it sometimes only averages 10 degrees Celsius.

The lighting conditions under which the respective plant species thrive depend on the respective vegetation levels. Plants that grow close to the ground are usually very shade-tolerant. In contrast, the lighting requirement is higher for climbing plants and epiphytically growing species.

Typical plant species in the tropical rainforest that are cared for as houseplants are bromeliads, orchids and philodendrons. They are suitable for keeping as a houseplant because they usually look attractive all year round and there is no need for a separate rest period for these plants.[16]

- Seasonally wet forests

In contrast to the tropical rainforests, the alternately moist or rain-green forests have rainy and dry periods. The species found there are adapted to these dry periods and have growing and resting periods. Successful maintenance of these species requires that these rest periods are observed.[17]

Typical plant species in the alternately moist forests, the varieties of which are cultivated as houseplants, are knight's stars and the clivien, which has been introduced as a houseplant since 1850.

- Savannah and desert

The open savannah landscape, which can be found in both the tropics and the subtropics, is subdivided into wet savannah, dry savannah and thorn bush savannah. Plant species in this habitat are very well adapted to temporary drought and low humidity. They are mostly succulents and cacti. However, it is important to note that cold storage in many species is necessary in winter in order to achieve flowering success next year.[18]

In addition to the cacti, various types of aloes, agaves, crassula, echeveria, euphorbia and sansevieria have spread as houseplants.

- Subtropics

The subtropics are characterized by a length of day that changes according to the season and a relatively mild winter with abundant rainfall. During the summer, precipitation occasionally occurs only occasionally and very high temperatures can be reached. Myrtle and oleanders as well as some species of ficus are houseplants that come from this vegetation zone.

- Temperate zone

Very few species of the plants cared for as indoor plants come from the temperate climate zone. Typical representatives are cultivated forms of ivy as well as Saxifraga stolonifera and Carex brunnea. They all only thrive if they are as cool as possible.[19]

Plant requirements

Both under-watering and over-watering can be detrimental to a houseplant. Different species of houseplants require different soil moisture levels. Brown crispy tips on a plant's leaves are a sign that the plant is under-watered. Yellowing leaves can show that the plant is over watered. Most plants can not withstand their roots sitting in water and will often lead to root rot. Most species of houseplant will tolerate low humidity environments if they're watered regularly. Different plants require different amounts of light, for different duration.[20]

Houseplants are generally grown in specialized soils called potting compost or potting soil. A good potting compost mixture includes soil conditioners to provide the plant with nutrients, support, adequate drainage, and proper aeration. Most potting composts contain a combination of peat and vermiculite or perlite. Plants require soil minerals, mainly nitrate, phosphate, and potassium. Houseplants do not have a continuous feed of nutrients unless they are fertilised regularly.[21] Phosphorus is essential for flowering or fruiting plants and potassium is essential for strong roots and increased nutrient uptake.[21]

House plants are generally planted in pots that have drainage holes in the bottom of the pot to reduce the likelihood of over watering and standing water. A pot that is too large will cause root disease because of the excess moisture retained in the soil, while a pot that is too small will restrict a plant's growth. Generally, a plant can stay in the same pot for two or so years. Pots come in a variety of types as well, but usually can be broken down into two groups: porous and non-porous. Porous pots provide better aeration as air passes laterally through the sides of the pot. Non-porous pots such as glazed or plastic pots tend to hold moisture longer and restrict airflow.

Alternative growing methods

Aside from traditional soil mixtures, media such as expanded clay may be employed in hydroponics, in which the plant is grown in a water and nutrient solution. Methods of soiless growing include growing plants in pots of water, sand, gravel, brick, even styrofoam. This technique has a number of benefits, including an odorless, reusable, and more hygienic media. Any habitat for soil-bound pests is also eliminated, and the plant's water supply is less variable. However, some plants do not grow well with this technique, and media is often difficult to find in some parts of the world, such as North America, where hydroponics and specifically hydroculture is not as well-known or widespread.

Subirrigation offers another alternative to top-watering techniques. In this approach the plant is watered from the bottom of the pot. Water is transferred up into the potting media (be it soil or others) by capillary action. Advantages of this technique include controlled amounts of water, resulting in lower chances of overwatering if done correctly, no need to drain plants after watering unlike traditional top-water methods, and less compaction of the media due to the pressure put on the media from top-watering.

Effect on indoor air pollution

Indoor plants reduce components of indoor air pollution, particularly volatile organic compounds (VOC) such as benzene, toluene, and xylene. These VOC's have been reported to reduce by about 50-75% with the presence of a houseplant. The compounds are removed primarily by soil microorganisms.[22] Some tests of benzene purification by houseplants noticed that plants can makeup and convert benzene, then transform it to a carbon use for future use.[23] Plants can also remove carbon dioxide, which is correlated with lower work performance, from indoor areas.[24] The effect has been investigated by NASA for use in spacecraft.[25] Plants also appear to reduce airborne microbes and increase humidity.[26]

VOCs are more common in indoor areas than outdoors.[27] This is because air and VOCs get trapped in indoor spaces; there is less air circulation.[27] There are over 350 known VOCs.[27] They are causative agents for “building-related illness” or “sick-building syndrome”.[28] Symptoms of this illness include: irritated eyes, nose or throat, headache, drowsiness and breathing problems.[27] These symptoms may not always be present, however, and chronic exposure may lead to lack of concentration and other health issues such as asthma and heart disease.[27] Urban dwellers spend up to 90% of their time indoors so they are at higher risk of experiencing the adverse effects of indoor air pollution.[28]

Common plants used to remediate indoor air pollutants include: English ivy (Hedera helix), Peace lily (Spathiphyllum ‘Mauna Loa’), Chinese evergreen (Aglaonema modestum), Bamboo palm (Chamaedorea seifrizii), and Chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum morifolium).[1] There are several studies that cite the plant microcosm as a mechanism to reduce indoor VOCs.[1][27] The roots of indoor houseplants have also been proven to remove VOCs. In general, plants have to suck up the pollutant with their stomata during gas transfers to remove the VOCs. Controls of just pots alone and just a tray of water suggest that it is the soil microcosm that provides the pollutant sink.[27] The role of the plants is to establish and maintain the species specific root-zone microbial communities.[27] This mechanism was first suggested by Wolverton et al. in 1985. Houseplants also aid in humidity, temperature, and noise control.[28]

NASA conducted a two-year study in 1989 to test the ability of houseplants or potting soil to remove several VOCs from the air.[1] The experiment included the chemicals benzene, TCE, and formaldehyde.[1] The study was conducted in airtight experimental chambers.[1] They found that bacterial counts correlated with increased chemical removal.[1] Another finding was that when the same plants and soil were constantly exposed to a chemical such as benzene, their capacity to clean the air increased over time.[1] This is because microorganisms have the ability to genetically adapt.[1] Therefore, they change over time in order to utilize the toxic chemicals more efficiently as a food source.[1] This phenomenon is used as a strategy to treat wastewater.[1]

Psychological effects

A 2015 study showed that active interaction with houseplants "can reduce physiological and psychological stress compared with mental work."[29] A critical review of the experimental literature concluded "The reviewed studies suggest that indoor plants can provide psychological benefits such as stress-reduction and increased pain tolerance. However, they also showed substantial heterogeneity in methods and results. We therefore have strong reservations about general claims that indoor plants cause beneficial psychological changes. It appears that benefits are contingent on features of the context in which the indoor plants are encountered and on characteristics of the people encountering them."[30]

The phenomenon of biophilia explains why houseplants have positive psychological effects. Biophilia describes humans’ subconscious need for a connection with nature.[31] This is why humans are fascinated by natural spectacles such as waves or a fire.[31] It also explains why gardening and spending time outdoors can have healing effects.[31] Having plants in indoor living areas can have positive effects on physiological, psychological and cognitive health.[31] There is an architectural design approach known as “complexity and order” that coincides with biophilic design.[31] Complexity and order is defined as, “the presence of rich sensory information that is configured with a coherent spatial hierarchy, similar to the occurrence of design in nature.[31]” Humans enjoy looking at things that are not boring but also not too complex. This design strategy is based on nature and human's response to designs in nature.[31] The presence of plants and nature-inspired designs "is restorative and not dull like the modern cookie cutter designs."[31]

List of common houseplants

Tropical and subtropical

- Aglaonema (Chinese evergreen)

- Alocasia

- Anthurium

- Aphelandra squarrosa (zebra plant)

- Araucaria heterophylla (Norfolk Island pine)

- Asparagus aethiopicus (asparagus fern)

- Aspidistra elatior (cast iron plant)

- Begonia species and cultivars

- Bromeliaceae (bromeliads)

- Calathea (prayer plants)

- Chamaedorea elegans (parlor palm)

- Dypsis lutescens (areca palm)

- Chlorophytum comosum (spider plant)

- Citrus, compact cultivars such as the Meyer lemon

- Cyclamen

- Dracaena

- Dieffenbachia (dumbcane)

- Epipremnum aureum (golden pothos)

- Ficus benjamina (weeping fig)

- Ficus elastica (rubber plant)

- Ficus lyrata (fiddle-leaf fig)

- Hippeastrum

- Hoya species

- Mimosa pudica (sensitive plant)

- Nephrolepis exaltata cv. Bostoniensis (Boston fern)

- Orchidaceae (orchids)

- Cattleya and intergeneric hybrids thereof (e.g. Brassolaeliocattleya, Sophrolaeliocattleya)

- Cymbidium

- Dendrobium

- Miltoniopsis

- Oncidium

- Paphiopedilum

- Phalaenopsis

- Peperomia species

- Philodendron species

- Maranta (prayer plant)

- Monstera (Swiss cheese plant)

- Saintpaulia (African violet)

- Sansevieria trifasciata (mother-inlaw's tongue)

- Schefflera arboricola (umbrella plant)

- Sinningia speciosa (gloxinia)

- Spathiphyllum (peace lily)

- Stephanotis floribunda (Madagascar jasmine)

- Tradescantia zebrina (purple wandering Jew)

- Pilea peperomioides

- Scindapsus pictus (satin pothos)

- Yucca species

Succulents

Note: Many of these plants are also tropical or subtropical.

- Aloe vera

- Cactaceae (cacti)

- Epiphyllum (orchid cacti)

- Mammillaria

- Opuntia (large genus that includes the prickly pear)

- Zygocactus (Christmas cactus)

- Gymnocalycium mihanovichii (chin cactus)

- Crassula ovata (jade plant)

- Echeveria

- Haworthia

- Senecio angulatus (creeping groundsel)

- Senecio rowleyanus (string of pearls)

Forced bulbs

Note: Many forced bulbs are also temperate.

- Crocus

- Hyacinthus (hyacinth)

- Narcissus (genus) (narcissus or daffodil)

Temperates

- Hedera helix (English ivy)

- Saxifraga stolonifera (strawberry begonia)

See also

References

- Wolverton, B.; Johnson, A.; Bounds, K. (1989). Interior Landscape Plants for Indoor Air Pollution Abatement. hdl:2060/19930073077.

- MacDonald, Elvin "The World Book of House Plants" Popular Books

- Jules Janick (6 April 2010). Horticultural Reviews. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 50–. ISBN 978-0-470-65087-5.

- Life In A Medieval Castle Medieval Gardens

- Senecio angulatus (Creeping Groundsel) MaltaWildPlants.com by Stephen Mifsud

- Alfred Byrd Graf: Tropica – Color Cyclopedia of Exotic Plants and Trees. Roehrs Company, New Jersey 1981 (second edition), ISBN 0-911266-16-X

- Our fascination with indoor potted plants has a long and colourful history by The Scotsman, 3rd January 2008

- How To Decorate a Victorian House with Plants – A brief history of the Victorian obsession with houseplants, which turned parlors into bowers by Old House Online Journal, June 21, 2011.

- 5 Houseplants That Changed History by Amanda Gutterman from Gardenista, November 11, 2013

- Climbing Groundsel (Senecio angulatus) by Weeds of Melbourne, July 10, 2019

- Return of the Spider Plant by Mark Gale, McCarthy & Stone. Retrieved 8 June 2020

- Garden and plant trends over the past 70 years by Homes To Love, April 6 2018

- Join the 1970s house plants revolution The Middle Sized Garden, November 5th, 2017

- Millennials Didn’t Invent Houseplants by Gray Chapman, Apartment Therapy, June 18 2019

- The retro plants to fill your home with right now by Alice Vincent, from Stylist. Retrieved 8 June 2020

- Fritz Encke: Kalt- und Warmhauspflanzen. 2. Auflage. Verlag Eugen Ulmer, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-8001-6191-5

- Moritz Bürki, Marianne Fuchs: Bildatlas Topfpflanzen für Zimmer und Balkon – Steckbriefe und Tabellen von A – Z, Verlag Eugen Ullmer, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-8001-4654-1

- Alfred Byrd Graf: Tropica – Color Cyclopedia of Exotic Plants and Trees. Roehrs Company, New Jersey 1981 (second edition), ISBN 0-911266-16-X

- Bernhard Rosenkranz: Gärtnern ohne Garten. Freude an Balkon- und Zimmerpflanzen. Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1987, ISBN 3-499-18347-1

- Chicago Botanical Garden, Indoor Gardening, Pantheon Books, New York, 1995, p. 182.

- "How to Care for Indoor Plants (Houseplants)". Planet Natural. 2012-12-08. Retrieved 2019-05-05.

- Sriprapat, Wararat; Strand, Stuart E. (2016-04-01). "A lack of consensus in the literature findings on the removal of airborne benzene by houseplants: Effect of bacterial enrichment". Atmospheric Environment. 131: 9–16. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2016.01.031. ISSN 1352-2310.

- Sriprapat, Wararat; Strand, Stuart E. (April 2016). "A lack of consensus in the literature findings on the removal of airborne benzene by houseplants: Effect of bacterial enrichment". Atmospheric Environment. 131: 9–16. Bibcode:2016AtmEn.131....9S. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2016.01.031.

- Tarran, Jane; Torpy, Fraser; Burchett, Margaret (2007). "Use of living pot-plants to cleanse indoor air – research review" (PDF). IAQVEC 2007: Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Indoor Air Quality, Ventilation and Energy Conservation in Buildings: Sustainable Built Environment. pp. 249–56. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.534.4181. ISBN 978-4-86163-070-5.

- Wolverton, BC (1988). Foliage plants for improving indoor air quality. hdl:2060/19930073015.

- Wolverton, B. C.; Wolverton, John D. (1996). "Interior plants: their influence on airborne microbes inside energy-efficient buildings" (PDF). Journal of the Mississippi Academy of Sciences. 41 (2): 99–105.

- Orwell, Ralph L.; Wood, Ronald A.; Burchett, Margaret D.; Tarran, Jane; Torpy, Fraser (19 September 2006). "The Potted-Plant Microcosm Substantially Reduces Indoor Air VOC Pollution: II. Laboratory Study". Water, Air, and Soil Pollution. 177 (1–4): 59–80. Bibcode:2006WASP..177...59O. doi:10.1007/s11270-006-9092-3.

- Wood, Ronald A.; Burchett, Margaret D.; Alquezar, Ralph; Orwell, Ralph L.; Tarran, Jane; Torpy, Fraser (20 July 2006). "The Potted-Plant Microcosm Substantially Reduces Indoor Air VOC Pollution: I. Office Field-Study". Water, Air, and Soil Pollution. 175 (1–4): 163–180. Bibcode:2006WASP..175..163W. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.466.4897. doi:10.1007/s11270-006-9124-z.

- Lee, Min-sun; Lee, Juyoung; Park, Bum-Jin; Miyazaki, Yoshifumi (28 April 2015). "Interaction with indoor plants may reduce psychological and physiological stress by suppressing autonomic nervous system activity in young adults: a randomized crossover study". Journal of Physiological Anthropology. 34 (1): 21. doi:10.1186/s40101-015-0060-8. PMC 4419447. PMID 25928639.

- Bringslimark, Tina; Hartig, Terry; Patil, Grete G. (December 2009). "The psychological benefits of indoor plants: A critical review of the experimental literature". Journal of Environmental Psychology. 29 (4): 422–433. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.05.001.

- Ryan, Catherine O.; Browning, William D; Clancy, Joseph O; Andrews, Scott L; Kallianpurkar, Namita B (12 July 2014). "BIOPHILIC DESIGN PATTERNS: Emerging Nature-Based Parameters for Health and Well-Being in the Built Environment". International Journal of Architectural Research: ArchNet-IJAR. 8 (2): 62. doi:10.26687/archnet-ijar.v8i2.436.

External links

| Wikiversity has learning resources about Houseplant care |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Houseplants. |

- Indoor Plants - Soil Mixes, HGIC (Home & Garden Information Center) 1456, Clemson University Cooperative Extension Service

- Potting Mixes for Certified Organic Production, National Sustainable Agriculture Information Service