Hot spring

A hot spring, hydrothermal spring, or geothermal spring is a spring produced by the emergence of geothermally heated groundwater that rises from the Earth's crust. While some of these springs contain water that is a safe temperature for bathing, others are so hot that immersion can result in injury or death.

.jpg)

Definitions

There is no universally accepted definition of a hot spring. For example, one can find the phrase hot spring defined as

- any geothermal spring[1]

- a spring with water temperatures above its surroundings[2]

- a natural spring with water temperature above human body temperature (normally between 36.5 and 37.5 °C (97.7 and 99.5 °F))[3][4][5]

- a thermal spring with water warmer than 36.7 °C (98 °F)[6][7]

- a natural spring of water greater than 21.1 °C (70 °F) (synonymous with thermal spring)[8][9][10][11]

- a natural discharge of groundwater with elevated temperatures[12]

- a type of thermal spring in which hot water is brought to the surface. The water temperature of a hot spring is usually 6.5 °C (12 °F) or more above mean air temperature.[13] Note that by this definition, "thermal spring" is not synonymous with the term "hot spring"

- a spring whose hot water is brought to the surface (synonymous with a thermal spring). The water temperature of the spring is usually 8.3 °C (15 °F) or more above the mean air temperature.[14]

- a spring with water above average ambient ground temperature.[15]

- a spring with water temperatures above 50 °C (122 °F)[16]

The related term "warm spring" is defined as a spring with water temperature less than a hot spring by many sources, although Pentecost et al. (2003) suggest that the phrase "warm spring" is not useful and should be avoided.[5] The US NOAA Geophysical Data Center defines a "warm spring" as a spring with water between 20 and 50 °C (68 and 122 °F).

Sources of heat

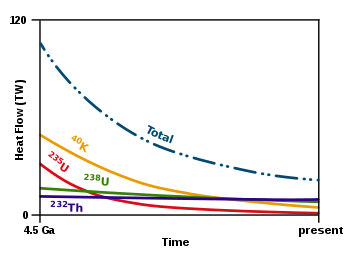

Much of the heat is created by decay of naturally radioactive elements. An estimated 45 to 90 percent of the heat escaping from the Earth originates from radioactive decay of elements mainly located in the mantle.[17][18][19] The major heat-producing isotopes in the Earth are potassium-40, uranium-238, uranium-235, and thorium-232.[20]

Water issuing from a hot spring is heated geothermally, that is, with heat produced from the Earth's mantle. In general, the temperature of rocks within the earth increases with depth. The rate of temperature increase with depth is known as the geothermal gradient. If water percolates deeply enough into the crust, it will be heated as it comes into contact with hot rocks. The water from hot springs in non-volcanic areas is heated in this manner.

In active volcanic zones such as Yellowstone National Park, water may be heated by coming into contact with magma (molten rock). The high temperature gradient near magma may cause water to be heated enough that it boils or becomes superheated. If the water becomes so hot that it builds steam pressure and erupts in a jet above the surface of the Earth, it is called a geyser. If the water only reaches the surface in the form of steam, it is called a fumarole. If the water is mixed with mud and clay, it is called a mud pot.

Note that hot springs in volcanic areas are often at or near the boiling point. People have been seriously scalded and even killed by accidentally or intentionally entering these springs.

Warm springs are sometimes the result of hot and cold springs mixing. They may occur within a volcanic area or outside of one. One example of a non-volcanic warm spring is Warm Springs, Georgia (frequented for its therapeutic effects by paraplegic U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who built the Little White House there).

Flow rates

Hot springs range in flow rate from the tiniest "seeps" to veritable rivers of hot water. Sometimes there is enough pressure that the water shoots upward in a geyser, or fountain.

High-flow hot springs

There are many claims in the literature about the flow rates of hot springs. There are many more high flow non-thermal springs than geothermal springs. For example, there are 33 recognized "magnitude one springs" (having a flow in excess of 2,800 L/s (99 cu ft/s) in Florida alone. Silver Springs, Florida has a flow of more than 21,000 L/s (740 cu ft/s). Springs with high flow rates include:

- The Excelsior Geyser Crater in Yellowstone National Park yields about 4,000 U.S. gal/min (0.25 m3/s).

- Evans Plunge in Hot Springs, South Dakota has a flow rate of 5,000 U.S. gal/min (0.32 m3/s) of 87 °F (31 °C) spring water. The Plunge, built in 1890, is the world's largest natural warm water indoor swimming pool.

- The combined flow of the 47 hot springs in Hot Springs, Arkansas is 35 L/s (1.2 cu ft/s).

- The hot spring of Saturnia, Italy with around 500 liters a second[21]

- The combined flow of the hot springs complex in Truth or Consequences, New Mexico is estimated at 99 liters/second.[22]

- Lava Hot Springs in Idaho has a flow of 130 liters/second.

- Glenwood Springs in Colorado has a flow of 143 liters/second.

- Elizabeth Springs in western Queensland, Australia might have had a flow of 158 liters/second in the late 19th century, but now has a flow of about 5 liters/second.

- Deildartunguhver in Iceland has a flow of 180 liters/second.

- The hot springs of Brazil's Caldas Novas ("New Hot Springs" in Portuguese) are tapped by 86 wells, from which 333 liters/second are pumped for 14 hours per day. This corresponds to a peak average flow rate of 3.89 liters/second per well.

- The 2,850 hot springs of Beppu in Japan are the highest flow hot spring complex in Japan. Together the Beppu hot springs produce about 1,592 liters/second, or corresponding to an average hot spring flow of 0.56 liters/second.

- The 303 hot springs of Kokonoe in Japan produce 1,028 liters/second, which gives the average hot spring a flow of 3.39 liters/second.

- Ōita Prefecture has 4,762 hot springs, with a total flow of 4,437 liters/second, so the average hot spring flow is 0.93 liters/second.

- The highest flow rate hot spring in Japan is the Tamagawa Hot Spring in Akita Prefecture, which has a flow rate of 150 liters/second. The Tamagawa Hot Spring feeds a 3 m (9.8 ft) wide stream with a temperature of 98 °C (208 °F).

- There are at least three hot springs in the Nage region 8 km (5.0 mi) south west of Bajawa in Indonesia that collectively produce more than 453.6 liters/second.

- There are another three large hot springs (Mengeruda, Wae Bana and Piga) 18 km (11 mi) north east of Bajawa, Indonesia that together produce more than 450 liters/second of hot water.

- The Dalhousie Springs complex in Australia had a peak total flow of more than 23,000 liters/second in 1915, giving the average spring in the complex an output of more than 325 liters/second. This has been reduced now to a peak total flow of 17,370 liters/second so the average spring has a peak output of about 250 liters/second.[23]

- In Yukon's Boreal Forest, 25 minutes north-west of Whitehorse in northern Canada, Takhini Hot Springs flows out of the Earth's interior at 385 L/min (85 imp gal/min; 102 US gal/min) and 47 °C (118 °F) year-round.[24]

Therapeutic uses

Because heated water can hold more dissolved solids than cold water, warm and especially hot springs, including beneficial sulphurous water,[25] often with very high mineral content, containing everything from simple calcium to lithium, and even radium. Because of both the folklore and the claimed medical value some of these springs have, they are often popular tourist destinations, and locations for rehabilitation clinics for those with disabilities.[26][27][28]

Precautions

A thermophile is an organism — a type of extremophile — that thrives at high temperatures, between 45 and 80 °C (113 and 176 °F).[29] Thermophiles are found in hot springs, as well as deep sea hydrothermal vents and decaying plant matter such as peat bogs and compost.

Some hot springs microbiota are infectious to humans:

- Naegleria fowleri, an excavate amoeba, lives in warm unsalted waters worldwide and causes a fatal meningitis should the organisms enter the nose.[30][31][32]

- Acanthamoeba also can spread through hot springs, according to the US Centers for Disease Control - The organisms enter through the eyes or via an open wound.[33]

- Legionella bacteria have been spread through hot springs.[34][35]

Examples

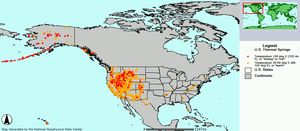

There are hot springs in many places and on all continents of the world. Countries that are renowned for their hot springs include China, Costa Rica, Iceland, Iran, Japan, New Zealand, Peru, Turkey, and the United States, but there are hot springs in many other places as well:

- Widely renowned since a chemistry professor's report in 1918 classified them as one of the world's most electrolytic mineral waters, the Rio Hondo Hot Springs in northern Argentina have become among the most visited on earth.[36] The Cacheuta Spa is another famous hot springs in Argentina.

- The springs in Europe with the highest temperatures are located in France, in a small village named Chaudes-Aigues. Located at the heart of the French volcanic region Auvergne, the thirty natural hot springs of Chaudes-Aigues have temperatures ranging from 45 °C (113 °F) to more than 80 °C (176 °F). The hottest one, the "Source du Par", has a temperature of 82 °C (179.6 °F). The hot waters running under the village have provided heat for the houses and for the church since the 14th Century. Chaudes-Aigues (Cantal, France) is a spa town known since the Roman Empire for the treatment of rheumatism.

- Carbonate aquifers in foreland tectonic settings can host important thermal springs although located in areas commonly not characterised by regional high heat flow values. In these cases, when thermal springs are located close or along the coastlines, the subaerial and/or submarine thermal springs constitute the outflow of marine groundwater, flowing through localised fractures and karstic rock-volumes. This is the case of springs occurring along the south-easternmost portion of the Apulia region (Southern Italy) where few sulphurous and warm waters (22-33 °C) outflow in partially submerged caves located along the Adriatic coast, thus supplying the historical spas of Santa Cesarea Terme. These springs are known from ancient times (Aristotele in III Century BC) and the physical-chemical features of their thermal waters resulted to be partly influenced by the sea level variations.[37]

- One of the highly potential geothermal energy reservoirs in India is the Tattapani thermal springs of Madhya Pradesh.[38][39]

- The silica-rich deposits found in Nili Patera, the volcanic caldera in Syrtis Major, Mars, are thought to be the remains of an extinct hot spring system.[40]

Etiquette

The customs and practices observed differ depending on the hot spring. It is common practice that bathers should wash before entering the water so as not to contaminate the water (with/without soap).[41] In many countries, like Japan, it is required to enter the hot spring with no clothes on, including swimwear. Typically in these circumstances, there are different facilities or times for men and women. In some countries, if it is a public hot spring, swimwear is required.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hot springs. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Hot springs. |

- Hotspot (geology)

- Hydrothermal vents

- Earliest known life forms

- Life timeline

- List of geothermal springs in the United Kingdom

- List of hot springs

- List of spa towns

- Mineral spring

- Onsen

- Taiwanese hot springs

- Valley of the Geysers

References

- "MSN Encarta definition of hot spring". Archived from the original on 2009-01-22.

- Miriam-Webster Online dictionary definition of hot spring

- Wordsmyth definition of hot spring

- American Heritage dictionary, fourth edition (2000) definition of hot spring Archived 2007-03-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Allan Pentecost; B. Jones; R.W. Renaut (2003). "What is a hot spring?". Can. J. Earth Sci. 40 (11): 1443–6. Bibcode:2003CaJES..40.1443P. doi:10.1139/e03-083. Archived from the original on 2007-03-11. provides a critical discussion of the definition of a hot spring.

- Infoplease definition of hot spring

- Random House Unabridged Dictionary, © Random House, Inc. 2006. definition of hot spring

- Wordnet 2.0 definition of hot spring

- Ultralingua Online Dictionary definition of hot spring

- Rhymezone definition of hot spring

- Lookwayup definition of hot spring

- Columbia Encyclopedia, sixth edition, article on hot spring Archived 2007-02-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Don L. Leet (1982). Physical Geology (6th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-669706-0.

A thermal spring is defined as a spring that brings warm or hot water to the surface.

Leet states that there are two types of thermal springs; hot springs and warm springs. - "Water Words Glossary - Hot Spring". NALMS. 2007. Archived from the original on January 14, 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-04.

- For example, ambient ground temperature is usually around 55–57 °F (13–14 °C) in the eastern United States

- US NOAA Geophysical Data Center definition

- Turcotte, DL; Schubert, G (2002). "4". Geodynamics (2nd ed.). Cambridge, England, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 136–7. ISBN 978-0-521-66624-4.

- Anuta, Joe (2006-03-30). "Probing Question: What heats the earth's core?". physorg.com. Retrieved 2007-09-19.

- Johnston, Hamish (19 July 2011). "Radioactive decay accounts for half of Earth's heat". PhysicsWorld.com. Institute of Physics. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- Sanders, Robert (2003-12-10). "Radioactive potassium may be major heat source in Earth's core". UC Berkeley News. Retrieved 2007-02-28.

- Terme di Saturnia Archived 2013-04-17 at the Wayback Machine, website

- John W. Lund; James C. Witcher (December 2002). "Truth or Consequences, New Mexico- A Spa City" (PDF). GHC Bulletin. 23 (4).

- W. F. Ponder (2002). "Desert Springs of Great Australian Arterial Basin". Conference Proceedings. Spring-fed Wetlands: Important Scientific and Cultural Resources of the Intermountain Region. Archived from the original on 2008-10-06. Retrieved 2013-04-06.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-02-26. Retrieved 2013-09-28.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Zuffianò, L. E.; Polemio, M.; Laviano, R.; De Giorgio, G.; Pallara, M.; Limoni, P. P.; Santaloia, F. (2018-07-06). "Sulphuric acid geofluid contribution on thermal carbonate coastal springs (Italy)". Environmental Earth Sciences. 77 (13): 517. doi:10.1007/s12665-018-7688-8. ISSN 1866-6299.

- The web site of the Roosevelt rehabilitation clinic in Warm Springs, Georgia Archived 2003-09-19 at the Wayback Machine

- "Web site of rehabilitation clinics in Central Texas created because of a geothermal spring". Archived from the original on 2018-06-01. Retrieved 2020-01-17.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-02-26. Retrieved 2013-09-28.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Analytical results for Takhini Hot Springs geothermal water:

- Madigan MT, Martino JM (2006). Brock Biology of Microorganisms (11th ed.). Pearson. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-13-196893-6.

- Naegleria at eMedicine

- Shinji Izumiyama; Kenji Yagita; Reiko Furushima-Shimogawara; Tokiko Asakura; Tatsuya Karasudani; Takuro Endo (July 2003). "Occurrence and Distribution of Naegleria Species in Thermal Waters in Japan". J Eukaryot Microbiol. 50: 514–5. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2003.tb00614.x. PMID 14736147.

- Yasuo Sugita; Teruhiko Fujii; Itsurou Hayashi; Takachika Aoki; Toshirou Yokoyama; Minoru Morimatsu; Toshihide Fukuma; Yoshiaki Takamiya (May 1999). "Primary amebic meningoencephalitis due to Naegleria fowleri: An autopsy case in Japan". Pathology International. 49 (5): 468–70. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1827.1999.00893.x. PMID 10417693.

- CDC description of acanthamoeba

- Miyamoto H, Jitsurong S, Shiota R, Maruta K, Yoshida S, Yabuuchi E (1997). "Molecular determination of infection source of a sporadic Legionella pneumonia case associated with a hot spring bath". Microbiol. Immunol. 41 (3): 197–202. doi:10.1111/j.1348-0421.1997.tb01190.x. PMID 9130230.

- Eiko Yabauuchi; Kunio Agata (2004). "An outbreak of legionellosis in a new facility of hot spring Bath in Hiuga City". Kansenshogaku Zasshi. 78 (2): 90–8. doi:10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi1970.78.90. ISSN 0387-5911. PMID 15103899.

- Welcome Argentina: Turismo en Argentina 2009

- Santaloia, F.; Zuffianò, L. E.; Palladino, G.; Limoni, P. P.; Liotta, D.; Minissale, A.; Brogi, A.; Polemio, M. (2016-11-01). "Coastal thermal springs in a foreland setting: The Santa Cesarea Terme system (Italy)". Geothermics. 64: 344–361. doi:10.1016/j.geothermics.2016.06.013. ISSN 0375-6505.

- Ravi Shanker; J.L. Thussu; J.M. Prasad (1987). "Geothermal studies at Tattapani hot spring area, Sarguja district, central India". Geothermics. 16 (1): 61–76. doi:10.1016/0375-6505(87)90079-4.

- D. Chandrasekharam; M.C. Antu (August 1995). "Geochemistry of Tattapani thermal springs, Himachal Pradesh, India—field and experimental investigations". Geothermics. 24 (4): 553–9. doi:10.1016/0375-6505(95)00005-B.

- Skok, J. R.; Mustard, J. F.; Ehlmann, B. L.; Milliken, R. E.; Murchie, S. L. (December 2010). "Silica deposits in the Nili Patera caldera on the Syrtis Major volcanic complex on Mars". Nature Geoscience. 3 (12): 838–841. doi:10.1038/ngeo990. ISSN 1752-0894.

- Fahr-Becker, Gabriele (2001). Ryokan. p. 24. ISBN 978-3-8290-4829-3.

Further reading

- Marjorie Gersh-Young (2011). Hot Springs and Hot Pools of the Southwest: Jayson Loam's Original Guide. Aqua Thermal Access. ISBN 978-1-890880-07-1.

- Marjorie Gersh-Young (2008). Hot Springs & Hot Pools Of The Northwest. Aqua Thermal Access. ISBN 978-1-890880-08-8.

- G. J Woodsworth (1999). Hot springs of Western Canada: a complete guide. West Vancouver: Gordon Soules. ISBN 978-0-919574-03-8.

- Clay Thompson (2003). "Tonopah: It's Water Under The Bush". Arizona Republic. p. B12.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Hot springs. |

- Thermal Springs List for the United States — 1,661 hot springs

- "Geothermal Resources of the Great Artesian Basin, Australia" (PDF). GHC Bulletin. 23 (2). June 2002.

- A scholarly paper with a map of over 20 geothermal areas in Uganda

- List of 100 thermal hot springs and hot pools in New Zealand

- List of hot springs worldwide