Convergent evolution

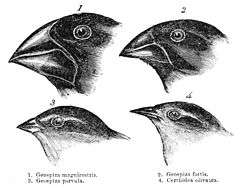

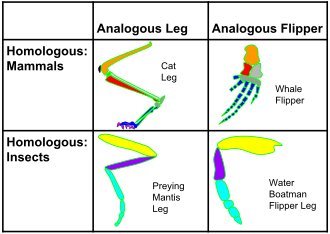

Convergent evolution is the independent evolution of similar features in species of different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last common ancestor of those groups. The cladistic term for the same phenomenon is homoplasy. The recurrent evolution of flight is a classic example, as flying insects, birds, pterosaurs, and bats have independently evolved the useful capacity of flight. Functionally similar features that have arisen through convergent evolution are analogous, whereas homologous structures or traits have a common origin but can have dissimilar functions. Bird, bat, and pterosaur wings are analogous structures, but their forelimbs are homologous, sharing an ancestral state despite serving different functions.

| Part of a series on |

| Evolutionary biology |

|---|

|

|

Key topics |

|

Fields and applications

|

|

Social implications

|

|

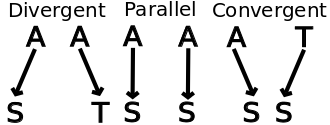

The opposite of convergence is divergent evolution, where related species evolve different traits. Convergent evolution is similar to parallel evolution, which occurs when two independent species evolve in the same direction and thus independently acquire similar characteristics; for instance, gliding frogs have evolved in parallel from multiple types of tree frog.

Many instances of convergent evolution are known in plants, including the repeated development of C4 photosynthesis, seed dispersal by fleshy fruits adapted to be eaten by animals, and carnivory.

Overview

In morphology, analogous traits arise when different species live in similar ways and/or a similar environment, and so face the same environmental factors. When occupying similar ecological niches (that is, a distinctive way of life) similar problems can lead to similar solutions.[1][2][3] The British anatomist Richard Owen was the first to identify the fundamental difference between analogies and homologies.[4]

In biochemistry, physical and chemical constraints on mechanisms have caused some active site arrangements such as the catalytic triad to evolve independently in separate enzyme superfamilies.[5]

In his 1989 book Wonderful Life, Stephen Jay Gould argued that if one could "rewind the tape of life [and] the same conditions were encountered again, evolution could take a very different course".[6] Simon Conway Morris disputes this conclusion, arguing that convergence is a dominant force in evolution, and given that the same environmental and physical constraints are at work, life will inevitably evolve toward an "optimum" body plan, and at some point, evolution is bound to stumble upon intelligence, a trait presently identified with at least primates, corvids, and cetaceans.[7]

Distinctions

Cladistics

In cladistics, a homoplasy is a trait shared by two or more taxa for any reason other than that they share a common ancestry. Taxa which do share ancestry are part of the same clade; cladistics seeks to arrange them according to their degree of relatedness to describe their phylogeny. Homoplastic traits caused by convergence are therefore, from the point of view of cladistics, confounding factors which could lead to an incorrect analysis.[8][9][10][11]

Atavism

In some cases, it is difficult to tell whether a trait has been lost and then re-evolved convergently, or whether a gene has simply been switched off and then re-enabled later. Such a re-emerged trait is called an atavism. From a mathematical standpoint, an unused gene (selectively neutral) has a steadily decreasing probability of retaining potential functionality over time. The time scale of this process varies greatly in different phylogenies; in mammals and birds, there is a reasonable probability of remaining in the genome in a potentially functional state for around 6 million years.[12]

Parallel vs. convergent evolution

When two species are similar in a particular character, evolution is defined as parallel if the ancestors were also similar, and convergent if they were not.[lower-alpha 2] Some scientists have argued that there is a continuum between parallel and convergent evolution, while others maintain that despite some overlap, there are still important distinctions between the two.[13][14][15]

When the ancestral forms are unspecified or unknown, or the range of traits considered is not clearly specified, the distinction between parallel and convergent evolution becomes more subjective. For instance, the striking example of similar placental and marsupial forms is described by Richard Dawkins in The Blind Watchmaker as a case of convergent evolution, because mammals on each continent had a long evolutionary history prior to the extinction of the dinosaurs under which to accumulate relevant differences.[16]

At molecular level

Proteins

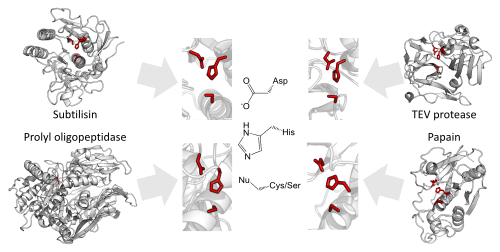

Protease active sites

The enzymology of proteases provides some of the clearest examples of convergent evolution. These examples reflect the intrinsic chemical constraints on enzymes, leading evolution to converge on equivalent solutions independently and repeatedly.[5][17]

Serine and cysteine proteases use different amino acid functional groups (alcohol or thiol) as a nucleophile. In order to activate that nucleophile, they orient an acidic and a basic residue in a catalytic triad. The chemical and physical constraints on enzyme catalysis have caused identical triad arrangements to evolve independently more than 20 times in different enzyme superfamilies.[5]

Threonine proteases use the amino acid threonine as their catalytic nucleophile. Unlike cysteine and serine, threonine is a secondary alcohol (i.e. has a methyl group). The methyl group of threonine greatly restricts the possible orientations of triad and substrate, as the methyl clashes with either the enzyme backbone or the histidine base. Consequently, most threonine proteases use an N-terminal threonine in order to avoid such steric clashes. Several evolutionarily independent enzyme superfamilies with different protein folds use the N-terminal residue as a nucleophile. This commonality of active site but difference of protein fold indicates that the active site evolved convergently in those families.[5][18]

Cone snail and fish insulin

Conus geographus produces a distinct form of insulin that is more similar to fish insulin protein sequences than to insulin from more closely related molluscs, suggesting convergent evolution.[19]

Na,K-ATPase and Insect resistance to cardenolides

Many examples of convergent evolution exist in insects in terms of developing resistance at a molecular level to toxins. One well-characterized example is the evolution of amino acid substitutions at well-defined positions in the structure of the Na,K-ATPase α-subunit spanning 15 genera and 4 orders. The synergistic relationship between the Q111 and N122 substitutions are highlighted. Convergent evolution in this case does not depend on the type of selection or time frame in which it can occur, but has more to do with the co-evolutionary relationship causing a sort of soft selection between cardenolide-producing plants and the insects that prey on them.[20]

Nucleic acids

Convergence occurs at the level of DNA and the amino acid sequences produced by translating structural genes into proteins. Studies have found convergence in amino acid sequences in echolocating bats and the dolphin;[21] among marine mammals;[22] between giant and red pandas;[23] and between the thylacine and canids.[24] Convergence has also been detected in a type of non-coding DNA, cis-regulatory elements, such as in their rates of evolution; this could indicate either positive selection or relaxed purifying selection.[25][26]

In animal morphology

Bodyplans

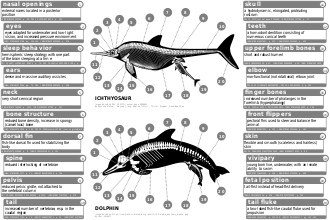

Swimming animals including fish such as herrings, marine mammals such as dolphins, and ichthyosaurs (of the Mesozoic) all converged on the same streamlined shape.[27][28] A similar shape and swimming adaptations are even present in molluscs, such as Phylliroe.[29] The fusiform bodyshape (a tube tapered at both ends) adopted by many aquatic animals is an adaptation to enable them to travel at high speed in a high drag environment.[30] Similar body shapes are found in the earless seals and the eared seals: they still have four legs, but these are strongly modified for swimming.[31]

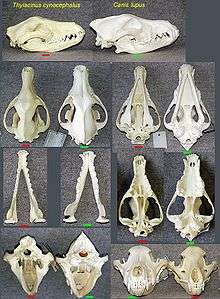

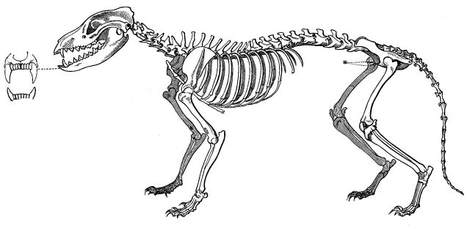

The marsupial fauna of Australia and the placental mammals of the Old World have several strikingly similar forms, developed in two clades, isolated from each other.[7] The body and especially the skull shape of the thylacine (Tasmanian tiger or Tasmanian wolf) converged with those of Canidae such as the red fox, Vulpes vulpes.[32]

Echolocation

As a sensory adaptation, echolocation has evolved separately in cetaceans (dolphins and whales) and bats, but from the same genetic mutations.[33][34]

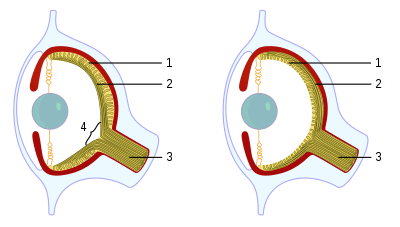

Eyes

One of the best-known examples of convergent evolution is the camera eye of cephalopods (such as squid and octopus), vertebrates (including mammals) and cnidaria (such as jellyfish).[36] Their last common ancestor had at most a simple photoreceptive spot, but a range of processes led to the progressive refinement of camera eyes — with one sharp difference: the cephalopod eye is "wired" in the opposite direction, with blood and nerve vessels entering from the back of the retina, rather than the front as in vertebrates. As a result, cephalopods lack a blind spot.[7]

Flight

Birds and bats have homologous limbs because they are both ultimately derived from terrestrial tetrapods, but their flight mechanisms are only analogous, so their wings are examples of functional convergence. The two groups have powered flight, evolved independently. Their wings differ substantially in construction. The bat wing is a membrane stretched across four extremely elongated fingers and the legs. The airfoil of the bird wing is made of feathers, strongly attached to the forearm (the ulna) and the highly fused bones of the wrist and hand (the carpometacarpus), with only tiny remnants of two fingers remaining, each anchoring a single feather. So, while the wings of bats and birds are functionally convergent, they are not anatomically convergent.[3][37] Birds and bats also share a high concentration of cerebrosides in the skin of their wings. This improves skin flexibility, a trait useful for flying animals; other mammals have a far lower concentration.[38] The extinct pterosaurs independently evolved wings from their fore- and hindlimbs, while insects have wings that evolved separately from different organs.[39]

Flying squirrels and sugar gliders are much alike in their body plans, with gliding wings stretched between their limbs, but flying squirrels are placental mammals while sugar gliders are marsupials, widely separated within the mammal lineage.[40]

Hummingbird hawk-moths and hummingbirds have evolved similar flight and feeding patterns.[41]

Insect mouthparts

Insect mouthparts show many examples of convergent evolution. The mouthparts of different insect groups consist of a set of homologous organs, specialised for the dietary intake of that insect group. Convergent evolution of many groups of insects led from original biting-chewing mouthparts to different, more specialised, derived function types. These include, for example, the proboscis of flower-visiting insects such as bees and flower beetles,[42][43][44] or the biting-sucking mouthparts of blood-sucking insects such as fleas and mosquitos.

Opposable thumbs

Opposable thumbs allowing the grasping of objects are most often associated with primates, like humans, monkeys, apes, and lemurs. Opposable thumbs also evolved in giant pandas, but these are completely different in structure, having six fingers including the thumb, which develops from a wrist bone entirely separately from other fingers.[45]

Primates

| ||

Convergent evolution in humans includes blue eye colour and light skin colour. When humans migrated out of Africa, they moved to more northern latitudes with less intense sunlight. It was beneficial to them to reduce their skin pigmentation. It appears certain that there was some lightening of skin colour before European and East Asian lineages diverged, as there are some skin-lightening genetic differences that are common to both groups. However, after the lineages diverged and became genetically isolated, the skin of both groups lightened more, and that additional lightening was due to different genetic changes.[46]

| Humans | Lemurs | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Despite the similarity of appearance, the genetic basis of blue eyes is different in humans and lemurs. | |||

Lemurs and humans are both primates. Ancestral primates had brown eyes, as most primates do today. The genetic basis of blue eyes in humans has been studied in detail and much is known about it. It is not the case that one gene locus is responsible, say with brown dominant to blue eye colour. However, a single locus is responsible for about 80% of the variation. In lemurs, the differences between blue and brown eyes are not completely known, but the same gene locus is not involved.[47]

In plants

Carbon fixation

While convergent evolution is often illustrated with animal examples, it has often occurred in plant evolution. For instance, C4 photosynthesis, one of the three major carbon-fixing biochemical processes, has arisen independently up to 40 times.[48][49] About 7,600 plant species of angiosperms use C4 carbon fixation, with many monocots including 46% of grasses such as maize and sugar cane,[50][51] and dicots including several species in the Chenopodiaceae and the Amaranthaceae.[52][53]

Fruits

A good example of convergence in plants is the evolution of edible fruits such as apples. These pomes incorporate (five) carpels and their accessory tissues forming the apple's core, surrounded by structures from outside the botanical fruit, the receptacle or hypanthium. Other edible fruits include other plant tissues;[54] for example, the fleshy part of a tomato is the walls of the pericarp.[55] This implies convergent evolution under selective pressure, in this case the competition for seed dispersal by animals through consumption of fleshy fruits.[56]

Seed dispersal by ants (myrmecochory) has evolved independently more than 100 times, and is present in more than 11,000 plant species. It is one of the most dramatic examples of convergent evolution in biology.[57]

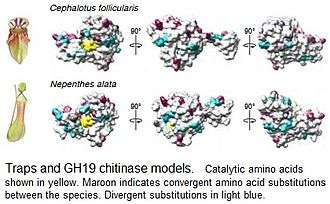

Carnivory

Carnivory has evolved multiple times independently in plants in widely separated groups. In three species studied, Cephalotus follicularis, Nepenthes alata and Sarracenia purpurea, there has been convergence at the molecular level. Carnivorous plants secrete enzymes into the digestive fluid they produce. By studying phosphatase, glycoside hydrolase, glucanase, RNAse and chitinase enzymes as well as a pathogenesis-related protein and a thaumatin-related protein, the authors found many convergent amino acid substitutions. These changes were not at the enzymes' catalytic sites, but rather on the exposed surfaces of the proteins, where they might interact with other components of the cell or the digestive fluid. The authors also found that homologous genes in the non-carnivorous plant Arabidopsis thaliana tend to have their expression increased when the plant is stressed, leading the authors to suggest that stress-responsive proteins have often been co-opted[lower-alpha 3] in the repeated evolution of carnivory.[58]

Methods of inference

Phylogenetic reconstruction and ancestral state reconstruction proceed by assuming that evolution has occurred without convergence. Convergent patterns may, however, appear at higher levels in a phylogenetic reconstruction, and are sometimes explicitly sought by investigators. The methods applied to infer convergent evolution depend on whether pattern-based or process-based convergence is expected. Pattern-based convergence is the broader term, for when two or more lineages independently evolve patterns of similar traits. Process-based convergence is when the convergence is due to similar forces of natural selection.[59]

Pattern-based measures

Earlier methods for measuring convergence incorporate ratios of phenotypic and phylogenetic distance by simulating evolution with a Brownian motion model of trait evolution along a phylogeny.[60][61] More recent methods also quantify the strength of convergence.[62] One drawback to keep in mind is that these methods can confuse long-term stasis with convergence due to phenotypic similarities. Stasis occurs when there is little evolutionary change among taxa.[59]

Distance-based measures assess the degree of similarity between lineages over time. Frequency-based measures assess the number of lineages that have evolved in a particular trait space.[59]

Process-based measures

Methods to infer process-based convergence fit models of selection to a phylogeny and continuous trait data to determine whether the same selective forces have acted upon lineages. This uses the Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU) process to test different scenarios of selection. Other methods rely on an a priori specification of where shifts in selection have occurred.[63]

See also

- Incomplete lineage sorting: the presence of multiple alleles in ancestral populations might lead to the impression that convergent evolution has occurred.

Notes

- However, evolutionary developmental biology has identified deep homology between insect and mammal body plans, to the surprise of many biologists.

- However, all organisms share a common ancestor more or less recently, so the question of how far back to look in evolutionary time and how similar the ancestors need to be for one to consider parallel evolution to have taken place is not entirely resolved within evolutionary biology.

- The prior existence of suitable structures has been called pre-adaptation or exaptation.

References

- Kirk, John Thomas Osmond (2007). Science & Certainty. Csiro Publishing. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-643-09391-1. Archived from the original on 2017-02-15. Retrieved 2017-01-23.

evolutionary convergence, which, quoting .. Simon Conway Morris .. is the 'recurring tendency of biological organization to arrive at the same "solution" to a particular "need". .. the 'Tasmanian tiger' .. looked and behaved like a wolf and occupied a similar ecological niche, but was in fact a marsupial not a placental mammal.

- Reece, J.; Meyers, N.; Urry, L.; Cain, M.; Wasserman, S.; Minorsky, P.; Jackson, R.; Cooke, B. (2011-09-05). Cambell Biology, 9th Edition. Pearson. p. 586. ISBN 978-1-4425-3176-5.

- "Homologies and analogies". University of California Berkeley. Archived from the original on 2016-11-19. Retrieved 2017-01-10.

- Thunstad, Erik (2009). Darwins teori, evolusjon gjennom 400 år (in Norwegian). Oslo, Norway: Humanist forlag. p. 404. ISBN 978-82-92622-53-7.

- Buller, A. R.; Townsend, C. A. (19 Feb 2013). "Intrinsic evolutionary constraints on protease structure, enzyme acylation, and the identity of the catalytic triad". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (8): E653–61. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110E.653B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1221050110. PMC 3581919. PMID 23382230.

- Gould, S.J. (1989). Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History. W.W. Norton. pp. 282–285. ISBN 978-0-09-174271-3.

- Conway Morris, Simon (2005). Life's solution: inevitable humans in a lonely universe. Cambridge University Press. pp. 164, 167, 170 and 235. doi:10.2277/0521827043. ISBN 978-0-521-60325-6. OCLC 156902715.

- Chirat, R.; Moulton, D. E.; Goriely, A. (2013). "Mechanical basis of morphogenesis and convergent evolution of spiny seashells". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (15): 6015–6020. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.6015C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1220443110. PMC 3625336. PMID 23530223.

- Lomolino, M; Riddle, B; Whittaker, R; Brown, J (2010). Biogeography, Fourth Edition. Sinauer Associates. p. 426. ISBN 978-0-87893-494-2.

- West-Eberhard, Mary Jane (2003). Developmental Plasticity and Evolution. Oxford University Press. pp. 353–376. ISBN 978-0-19-512235-0.

- Sanderson, Michael J.; Hufford, Larry (1996). Homoplasy: The Recurrence of Similarity in Evolution. Academic Press. pp. 330, and passim. ISBN 978-0-08-053411-4. Archived from the original on 2017-02-14. Retrieved 2017-01-21.

- Collin, R.; Cipriani, R. (2003). "Dollo's law and the re-evolution of shell coiling". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 270 (1533): 2551–2555. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2517. PMC 1691546. PMID 14728776.

- Arendt, J; Reznick, D (January 2008). "Convergence and parallelism reconsidered: what have we learned about the genetics of adaptation?". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 23 (1): 26–32. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2007.09.011. PMID 18022278.

- Pearce, T. (10 November 2011). "Convergence and Parallelism in Evolution: A Neo-Gouldian Account". The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science. 63 (2): 429–448. doi:10.1093/bjps/axr046.

- Zhang, J.; Kumar, S. (1997). "Detection of convergent and parallel evolution at the amino acid sequence level". Mol. Biol. Evol. 14 (5): 527–36. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025789. PMID 9159930.

- Dawkins, Richard (1986). The Blind Watchmaker. W. W. Norton. pp. 100–106. ISBN 978-0-393-31570-7.

- Dodson, G.; Wlodawer, A. (September 1998). "Catalytic triads and their relatives". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 23 (9): 347–52. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(98)01254-7. PMID 9787641.

- Ekici, O. D.; Paetzel, M.; Dalbey, R. E. (December 2008). "Unconventional serine proteases: variations on the catalytic Ser/His/Asp triad configuration". Protein Science. 17 (12): 2023–37. doi:10.1110/ps.035436.108. PMC 2590910. PMID 18824507.

- Safavi-Hemami, Helena; Gajewiak, Joanna; Karanth, Santhosh; Robinson, Samuel D.; Ueberheide, Beatrix; Douglass, Adam D.; Schlegel, Amnon; Imperial, Julita S.; Watkins, Maren; Bandyopadhyay, Pradip K.; Yandell, Mark; Li, Qing; Purcell, Anthony W.; Norton, Raymond S.; Ellgaard, Lars; Olivera, Baldomero M. (10 February 2015). "Specialized insulin is used for chemical warfare by fish-hunting cone snails". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (6): 1743–1748. doi:10.1073/pnas.1423857112.

- Dobler, S., Dalla, S., Wagschal, V., & Agrawal, A. A. (2012). Community-wide convergent evolution in insect adaptation to toxic cardenolides by substitutions in the Na,K-ATPase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(32), 13040–13045. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1202111109

- Parker, J.; Tsagkogeorga, G; Cotton, J. A.; Liu, Y.; Provero, P.; Stupka, E.; Rossiter, S. J. (2013). "Genome-wide signatures of convergent evolution in echolocating mammals". Nature. 502 (7470): 228–231. Bibcode:2013Natur.502..228P. doi:10.1038/nature12511. PMC 3836225. PMID 24005325.

- Foote, Andrew D.; Liu, Yue; Thomas, Gregg W. C.; Vinař, Tomáš; Alföldi, Jessica; Deng, Jixin; Dugan, Shannon; Elk, Cornelis E. van; Hunter, Margaret E. (March 2015). "Convergent evolution of the genomes of marine mammals". Nature Genetics. 47 (3): 272–275. doi:10.1038/ng.3198. PMC 4644735. PMID 25621460.

- Hu, Yibo; Wu, Qi; Ma, Shuai; Ma, Tianxiao; Shan, Lei; Wang, Xiao; Nie, Yonggang; Ning, Zemin; Yan, Li (January 2017). "Comparative genomics reveals convergent evolution between the bamboo-eating giant and red pandas". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 114 (5): 1081–1086. doi:10.1073/pnas.1613870114. PMC 5293045. PMID 28096377.

- Feigin, Charles Y.; Newton, Axel H.; Doronina, Liliya; Schmitz, Jürgen; Hipsley, Christy A.; Mitchell, Kieren J.; Gower, Graham; Llamas, Bastien; Soubrier, Julien (January 2018). "Genome of the Tasmanian tiger provides insights into the evolution and demography of an extinct marsupial carnivore". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2 (1): 182–192. doi:10.1038/s41559-017-0417-y. PMID 29230027.

- Partha, Raghavendran; Chauhan, Bharesh K; Ferreira, Zelia; Robinson, Joseph D; Lathrop, Kira; Nischal, Ken K.; Chikina, Maria; Clark, Nathan L. (October 2017). "Subterranean mammals show convergent regression in ocular genes and enhancers, along with adaptation to tunneling". eLife. 6. doi:10.7554/eLife.25884. PMC 5643096. PMID 29035697.

- Sackton, TB; Grayson, P; Cloutier, A; Hu, Z; Liu, JS; Wheeler, NE; Gardner, PP; Clarke, JA; Baker, AJ; Clamp, M; Edwards, SV (5 April 2019). "Convergent regulatory evolution and loss of flight in paleognathous birds". Science. 364 (6435): 74–78. doi:10.1126/science.aat7244. PMID 30948549.

- "How do analogies evolve?". University of California Berkeley. Archived from the original on 2017-04-02. Retrieved 2017-01-26.

- Selden, Paul; Nudds, John (2012). Evolution of Fossil Ecosystems (2nd ed.). CRC Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-1-84076-623-3. Archived from the original on 2017-02-15. Retrieved 2017-01-26.

- Helm, R. R. (2015-11-18). "Meet Phylliroe: the sea slug that looks and swims like a fish". Deep Sea News. Archived from the original on 2019-07-26. Retrieved 2019-07-26.

- Ballance, Lisa (2016). "The Marine Environment as a Selective Force for Secondary Marine Forms" (PDF). UCSD. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-02-02. Retrieved 2019-09-19.

- Lento, G. M.; Hickson, R. E.; Chambers, G. K.; Penny, D. (1995). "Use of spectral analysis to test hypotheses on the origin of pinnipeds". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 12 (1): 28–52. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040189. PMID 7877495. Archived from the original on 2008-10-07. Retrieved 2013-10-16.

- Werdelin, L. (1986). "Comparison of Skull Shape in Marsupial and Placental Carnivores". Australian Journal of Zoology. 34 (2): 109–117. doi:10.1071/ZO9860109.

- Pennisi, Elizabeth (4 September 2014). "Bats and Dolphins Evolved Echolocation in Same Way". American Association for the Advancement of Science. Archived from the original on 25 December 2016. Retrieved 2017-01-15.

- Liu, Yang; Cotton, James A.; Shen, Bin; Han, Xiuqun; Rossiter, Stephen J.; Zhang, Shuyi (2010-01-01). "Convergent sequence evolution between echolocating bats and dolphins". Current Biology. 20 (2): R53–R54. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.11.058. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 20129036. Archived from the original on 2013-06-05. Retrieved 2017-05-12.

- Roberts, M.B.V. (1986). Biology: A Functional Approach. Nelson Thornes. p. 274. ISBN 978-0-17-448019-8. Archived from the original on 2016-09-12.

- Kozmik, Z; Ruzickova, J; Jonasova, K; Matsumoto, Y.; Vopalensky, P.; Kozmikova, I.; Strnad, H.; Kawamura, S.; Piatigorsky, J.; Paces, V.; Vlcek, C. (1 July 2008). "From the Cover: Assembly of the cnidarian camera-type eye from vertebrate-like components". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (26): 8989–8993. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.8989K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0800388105. PMC 2449352. PMID 18577593.

- "Plant and Animal Evolution". University of Waikato. Archived from the original on 2017-03-18. Retrieved 2017-01-10.

- Ben-Hamo, Miriam; Muñoz-Garcia, Agustí; Larrain, Paloma; Pinshow, Berry; Korine, Carmi; Williams, Joseph B. (June 2016). "The cutaneous lipid composition of bat wing and tail membranes: a case of convergent evolution with birds". Proc. R. Soc. B. 283 (1833): 20160636. doi:10.1098/rspb.2016.0636. PMC 4936036. PMID 27335420.

- Alexander, David E. (2015). On the Wing: Insects, Pterosaurs, Birds, Bats and the Evolution of Animal Flight. Oxford University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-19-999679-7. Archived from the original on 2017-02-14. Retrieved 2017-01-21.

- "Analogy: Squirrels and Sugar Gliders". University of California Berkeley. Archived from the original on 2017-01-27. Retrieved 2017-01-10.

- Herrera, Carlos M. (1992). "Activity pattern and thermal biology of a day-flying hawkmoth (Macroglossum stellatarum) under Mediterranean summer conditions". Ecological Entomology. 17: 52–56. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2311.1992.tb01038.x. hdl:10261/44693.

- Krenn, Harald W.; Plant, John D.; Szucsich, Nikolaus U. (2005). "Mouthparts of flower-visiting insects". Arthropod Structure & Development. 34 (1): 1–40. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2004.10.002.

- Bauder, Julia A.S.; Lieskonig, Nora R.; Krenn, Harald W. (2011). "The extremely long-tongued Neotropical butterfly Eurybia lycisca (Riodinidae): Proboscis morphology and flower handling". Arthropod Structure & Development. 40 (2): 122–7. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2010.11.002. PMC 3062012. PMID 21115131.

- Wilhelmi, Andreas P.; Krenn, Harald W. (2012). "Elongated mouthparts of nectar-feeding Meloidae (Coleoptera)". Zoomorphology. 131 (4): 325–37. doi:10.1007/s00435-012-0162-3.

- "When is a thumb a thumb?". Understanding Evolution. Archived from the original on 2015-10-16. Retrieved 2015-08-14.

- Edwards, M.; et al. (2010). "Association of the OCA2 Polymorphism His615Arg with Melanin Content in East Asian Populations: Further Evidence of Convergent Evolution of Skin Pigmentation". PLOS Genetics. 6 (3): e1000867. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000867. PMC 2832666. PMID 20221248.

- Meyer, W. K.; et al. (2013). "The convergent evolution of blue iris pigmentation in primates took distinct molecular paths". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 151 (3): 398–407. doi:10.1002/ajpa.22280. PMC 3746105. PMID 23640739.

- Williams, B. P.; Johnston, I. G.; Covshoff, S.; Hibberd, J. M. (September 2013). "Phenotypic landscape inference reveals multiple evolutionary paths to C4 photosynthesis". eLife. 2: e00961. doi:10.7554/eLife.00961. PMC 3786385. PMID 24082995.

- Osborne, C. P.; Beerling, D. J. (2006). "Nature's green revolution: the remarkable evolutionary rise of C4 plants". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 361 (1465): 173–194. doi:10.1098/rstb.2005.1737. PMC 1626541. PMID 16553316.

- Sage, Rowan; Russell Monson (1999). "16". C4 Plant Biology. pp. 551–580. ISBN 978-0-12-614440-6.

- Zhu, X. G.; Long, S. P.; Ort, D. R. (2008). "What is the maximum efficiency with which photosynthesis can convert solar energy into biomass?". Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 19 (2): 153–159. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2008.02.004. PMID 18374559. Archived from the original on 2019-04-01. Retrieved 2018-12-29.

- Sage, Rowan; Russell Monson (1999). "7". C4 Plant Biology. pp. 228–229. ISBN 978-0-12-614440-6.

- Kadereit, G.; Borsch, T.; Weising, K.; Freitag, H (2003). "Phylogeny of Amaranthaceae and Chenopodiaceae and the Evolution of C4 Photosynthesis". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 164 (6): 959–86. doi:10.1086/378649.

- Ireland, Hilary, S.; et al. (2013). "Apple SEPALLATA1/2 -like genes control fruit flesh development and ripening". The Plant Journal. 73 (6): 1044–1056. doi:10.1111/tpj.12094. PMID 23236986.

- Heuvelink, Ep (2005). Tomatoes. CABI. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-84593-149-0. Archived from the original on 2019-04-01. Retrieved 2016-12-17.

- Lorts, C.; Briggeman, T.; Sang, T. (2008). "Evolution of fruit types and seed dispersal: A phylogenetic and ecological snapshot" (PDF). Journal of Systematics and Evolution. 46 (3): 396–404. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-07-18.

- Lengyel, S.; Gove, A. D.; Latimer, A. M.; Majer, J. D.; Dunn, R. R. (2010). "Convergent evolution of seed dispersal by ants, and phylogeny and biogeography in flowering plants: a global survey". Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics. 12: 43–55. doi:10.1016/j.ppees.2009.08.001.

- Fukushima, K; Fang, X; et al. (2017). "Genome of the pitcher plant Cephalotus reveals genetic changes associated with carnivory". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 1 (3): 0059. doi:10.1038/s41559-016-0059. PMID 28812732.

- Stayton, C. Tristan (2015). "The definition, recognition, and interpretation of convergent evolution, and two new measures for quantifying and assessing the significance of convergence". Evolution. 69 (8): 2140–2153. doi:10.1111/evo.12729. PMID 26177938.

- Stayton, C. Tristan (2008). "Is convergence surprising? An examination of the frequency of convergence in simulated datasets". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 252 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.01.008. PMID 18321532.

- Muschick, Moritz; Indermaur, Adrian; Salzburger, Walter (2012). "Convergent Evolution within an Adaptive Radiation of Cichlid Fishes". Current Biology. 22 (24): 2362–2368. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.10.048. PMID 23159601.

- Arbuckle, Kevin; Bennett, Cheryl M.; Speed, Michael P. (July 2014). "A simple measure of the strength of convergent evolution". Methods in Ecology and Evolution. 5 (7): 685–693. doi:10.1111/2041-210X.12195.

- Ingram, Travis; Mahler, D. Luke (2013-05-01). "SURFACE: detecting convergent evolution from comparative data by fitting Ornstein-Uhlenbeck models with stepwise Akaike Information Criterion". Methods in Ecology and Evolution. 4 (5): 416–425. doi:10.1111/2041-210X.12034.

Further reading

- Jonathan B. Losos (2017). Improbable Destinies: Fate, Chance, and the Future of Evolution. Riverhead Books. ISBN 978-0399184925.

_%EC%A0%9C%EC%9E%91%EA%B8%B0%EC%98%81%EC%83%81_%EC%97%84%EC%A0%95%ED%99%94_3m3s.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)