Macraucheniidae

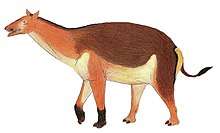

Macraucheniidae is a family in the extinct South American ungulate order Litopterna, that resembled various camelids. The reduced nasal bones of their skulls was originally suggested to have housed a small proboscis, similar to that of the saiga antelope.[2] However, one study suggests that they were openings for large moose-like nostrils.[3] Their hooves were similar to those of rhinoceroses today, with a simple ankle joint and three digits on each foot. Thus, they may have been capable of rapid directional change when running away from predators, such as large phorusrhacid terror birds, sparassodont metatherians, giant short-faced bears (Arctotherium) and saber-toothed cats (Smilodon). Macraucheniids probably lived in large herds to gain protection against these predators, as well as to facilitate finding mates for reproduction.

| Macraucheniidae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Interpretation of Macrauchenia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | †Litopterna |

| Superfamily: | †Macrauchenioidea |

| Family: | †Macraucheniidae Gill, 1872 |

| Subfamilies | |

| |

The family Macraucheniidae includes genera such as Theosodon, Xenorhinotherium, and Macrauchenia. Macrauchenia is the best-known and most recent macraucheniid. It became extinct during the Pleistocene Epoch. It was one of the few litopterns to survive the ecological pressures of the Great American Interchange between North and South America, which took place after the Isthmus of Panama rose above sea level some 3 million years ago. It may instead have died out in the aftermath of the invasion of the Americas by human hunters. When Macrauchenia died out, so too did the Macraucheniidae and the entire litoptern order.

Sequencing of mitochondrial DNA extracted from a Macrauchenia patachonica fossil from a cave in southern Chile indicates that Macrauchenia (and by inference, Litopterna) is the sister group to Perissodactyla, with an estimated divergence date of 66 million years ago.[4] Analysis of collagen sequences obtained from Macrauchenia and Toxodon gave the same conclusion, adding notoungulates to the sister group clade.[5][6]

Subdivision

Subfamily Cramaucheniinae

- Caliphrium

- Coniopternum

- Cramauchenia

- Notodiaphorus

- Phoenixauchenia

- Pternoconius

- Theosodon

Subfamily Macraucheniinae

- Cullinia

- Macrauchenia

- Huayqueriana (synonym Macrauchenidia)[7]

- Oxyodontherium

- Macraucheniopsis

- Oxyodontherium

- Paranauchenia

- Promacrauchenia

- Scalabrinitherium

- Windhausenia

- Xenorhinotherium

Subfamily Sparnotheriodontinae

- Decaconus

- Guilielmofloweria

- Megacrodon

- Oroacrodon

- Periacrodon

- Phoradiadius

- Polymorphis

- Sparnotheriodon

- Victorlemoinea (=Sparnotheriodon?)

References

- Dozo, M.T. & Vera, B. (2010). "First skull and associated postcranial bones of Macraucheniidae (Mammalia, Litopterna) from the Deseadan SALMA (late Oligocene) of Cabeza Blanca (Chubut, Argentina)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (6): 1818–1826. doi:10.1080/02724634.2010.520781.

- The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. 1999. p. 248. ISBN 978-1-84028-152-1.

- "Cranial characters associated with the proboscis postnatal-development in Tapirus (Perissodactyla: Tapiridae) and comparisons with other extant and fossil hoofed mammals | Request PDF". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2019-04-11.

- Westbury, M.; Baleka, S.; Barlow, A.; Hartmann, S.; Paijmans, J. L. A.; Kramarz, A.; Forasiepi, A. M.; Bond, M.; Gelfo, J. N.; Reguero, M. A.; López-Mendoza, P.; Taglioretti, M.; Scaglia, F.; Rinderknecht, A.; Jones, W.; Mena, F.; Billet, G.; de Muizon, C.; Aguilar, J. L.; MacPhee, R. D. E.; Hofreiter, M. (2017-06-27). "A mitogenomic timetree for Darwin's enigmatic South American mammal Macrauchenia patachonica". Nature Communications. 8: 15951. doi:10.1038/ncomms15951. PMC 5490259. PMID 28654082.

- Welker, F.; Collins, M. J.; Thomas, J. A.; Wadsley, M.; Brace, S.; Cappellini, E.; Turvey, S. T.; Reguero, M.; Gelfo, J. N.; Kramarz, A.; Burger, J.; Thomas-Oates, J.; Ashford, D. A.; Ashton, P. D.; Rowsell, K.; Porter, D. M.; Kessler, B.; Fischer, R.; Baessmann, C.; Kaspar, S.; Olsen, J. V.; Kiley, P.; Elliott, J. A.; Kelstrup, C. D.; Mullin, V.; Hofreiter, M.; Willerslev, E.; Hublin, J.-J.; Orlando, L.; Barnes, I.; MacPhee, R. D. E. (2015-03-18). "Ancient proteins resolve the evolutionary history of Darwin's South American ungulates". Nature. 522 (7554): 81–84. doi:10.1038/nature14249. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 25799987.

- Buckley, M. (2015-04-01). "Ancient collagen reveals evolutionary history of the endemic South American 'ungulates'". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 282 (1806): 20142671. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.2671. PMC 4426609. PMID 25833851.

- Forasiepi et al., 2016, p.11

Bibliography

- Forasiepi, Analía M.; Ross D.E. MacPhee; Santiago Hernández del Pino; Gabriela I. Schmidt; Eli Amson, and Camille Grohé. 2016. Exceptional skull of Huayqueriana (Mammalia, Litopterna, Macraucheniidae) from the Late Miocene of Argentina: anatomy, systematics and paleobiological implications. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 404. 1–76. Accessed 2018-10-01.