History of the metric system

The history of the metric system began in the Age of Enlightenment with notions of length and weight taken from natural ones, and decimal multiples and fractions of them. The system became the standard of France and Europe in half a century. Other dimensions with unity ratios[Note 1] were added, and it went on to be adopted by the world.

The first practical realisation of the metric system came in 1799, during the French Revolution, when the existing system of measures, which had become impractical for trade, was replaced by a decimal system based on the kilogram and the metre. The basic units were taken from the natural world: the unit of length, the metre, was based on the dimensions of the Earth, and the unit of mass, the kilogram, was based on the mass of water having a volume of one litre or a cubic decimetre. Reference copies for both units were manufactured in platinum and remained the standards of measure for the next 90 years. After a period of reversion to the mesures usuelles due to unpopularity of the metric system, the metrication of France as well as much of Europe was complete by mid-century.

In the middle of the 19th century, James Clerk Maxwell put forward the concept of a coherent system where a small number of units of measure were defined as base units, and all other units of measure, called derived units, were defined in terms of the base units. Maxwell proposed three base units: length, mass and time. Advances in electromagnetism in the 19th century necessitated new units to be defined, and multiple incompatible systems of such units came into use; none could be reconciled with the existing system of mechanical units. This impasse was resolved by Giovanni Giorgi, who in 1901 proved that a coherent system that incorporated electromagnetic units had to have an electromagnetic unit as a fourth base unit.

The seminal 1875 Treaty of the Metre resulted in the fashioning and distribution of metre and kilogram artefacts, the standards of the future coherent system that became the SI, and the creation of an international body Conférence générale des poids et mesures or CGPM to oversee systems of weights and measures based on them.

In 1960, the CGPM launched the International System of Units (in French the Système international d'unités or SI) which had six "base units": the metre, kilogram, second, ampere, degree Kelvin (subsequently renamed the "kelvin") and candela; as well as 16 further units derived from the base units. A seventh base unit, the mole, and six further derived units were added later in the 20th century. During this period, the metre was redefined in terms of the speed of light, and the second was redefined in terms of the microwave frequency of a caesium atomic clock.

Due to the instability of the international prototype of the kilogram, a series of initiatives were undertaken, starting in the late 20th century, to redefine the ampere, kilogram, mole and kelvin in terms of invariant constants of physics, ultimately resulting in the 2019 redefinition of the SI base units, which finally eliminated the need for any physical reference objects.

Age of Enlightenment

Foundational aspects of mathematics and culture, together with advances in the sciences during the Enlightenment, set the stage for the emergence in the late 18th century of a system of measurement with rationally related units and simple rules for combining them.

Preamble

In the early ninth century, when much of what later became France was part of the Holy Roman Empire, units of measure had been standardised by the Emperor Charlemagne. He had introduced standard units of measure for length and for mass throughout his empire. As the empire disintegrated into separate nations, including France, these standards diverged. In England the Magna Carta (1215) had stipulated that "There shall be standard measures of wine, ale, and corn (the London quarter), throughout the kingdom. There shall also be a standard width of dyed cloth, russet, and haberject, namely two ells within the selvedges. Weights are to be standardised similarly."[1]

During the early medieval era, Roman numerals were used in Europe to represent numbers,[2] but the Arabs represented numbers using the Hindu numeral system, a positional notation that used ten symbols. In about 1202, Fibonacci published his book Liber Abaci (Book of Calculation) which introduced the concept of positional notation into Europe. These symbols evolved into the numerals "0", "1", "2" etc.[3][4] At that time there was dispute regarding the difference between rational numbers and irrational numbers and there was no consistency in the way in which decimal fractions were represented.

Simon Stevin is credited with introducing the decimal system into general use in Europe.[5] In 1586, he published a small pamphlet called De Thiende ("the tenth") which historians credit as being the basis of modern notation for decimal fractions.[6] Stevin felt that this innovation was so significant that he declared the universal introduction of decimal coinage, measures, and weights to be merely a question of time.[5][7]:70[8]:91

Body measures and artefacts

Since the time of Charlemagne, the standard of length had been a measure of the body, that from fingertip to fingertip of the outstretched arms of a large man,[Note 2] from a family of body measures called fathoms, originally used among other things, to measure depth of water. An artefact to represent the standard was cast in the most durable substance available in the Middle Ages, an iron bar . The problems of a non-reproducible artefact became apparent over the ages: it rusted, was stolen, beaten into a mortised wall until it bent, and was at times lost. When a new royal standard had to be cast, it was a different standard than the old one, so replicas of old ones and new ones came into existence and use. The artefact existed through the 18th century, and was called a teise or later, a toise (from Latin tense: outstretched (arms)). This would lead to a search in the 18th century for a reproducible standard based on some invariant measure of the natural world.

Clocks and pendulums

In 1656, Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens invented the pendulum clock, with its pendulum marking the seconds. This gave rise to proposals to use its length as a standard unit. But it became apparent that the pendulum lengths of calibrated clocks in different locations varied (due to local variations in the acceleration due to gravity), and this was not a good solution. A more uniform standard was needed.

In 1670, Gabriel Mouton, a French abbot and astronomer, published the book Observationes diametrorum solis et lunae apparentium ("Observations of the apparent diameters of the Sun and Moon") in which he proposed a decimal system of measurement of length for use by scientists in international communication, to be based on the dimensions of the Earth. The milliare would be defined as a minute of arc along a meridian and would be divided into 10 centuria, the centuria into 10 decuria and so on, successive units being the virga, virgula, decima, centesima, and the millesima. Mouton used Riccioli's estimate that one degree of arc was 321,185 Bolognese feet, and his own experiments showed that a pendulum of length one virgula would beat 3959.2 times[Note 3] in half an hour.[9][Note 4] He believed that with this information scientists in a foreign country would be able to construct a copy of the virgula for their own use.[10] Mouton's ideas attracted interest at the time; Picard in his work Mesure de la Terre (1671) and Huygens in his work Horologium Oscillatorium sive de motu pendulorum ("Of oscillating clocks, or concerning the motion of pendulums", 1673) both proposing that a standard unit of length be tied to the beat frequency of a pendulum.[11][10]

The shape and size of the Earth

Since at least the Middle Ages, the Earth had been perceived as eternal, unchanging and of symmetrical shape (close to a sphere), so it was natural that some fractional measure of its surface should be proposed as a standard of length. But first, scientific information about the shape and size of the Earth had to be obtained.

In 1669, Jean Picard, a French astronomer, was the first person to measure the Earth accurately. In a survey spanning one degree of latitude, he erred by only 0.44%.

In Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1686), Isaac Newton gave a theoretical explanation for the "bulging equator"[Note 5] which also explained the differences found in the lengths of the "second pendulums",[12] theories that were confirmed by the French Geodesic Mission to Peru undertaken by the French Academy of Sciences in 1735.[13]

Late 18th century: conflict and lassitude

By the mid-18th century, it had become apparent that it was necessary to standardise of weights and measures between nations who traded and exchanged scientific ideas with each other. Spain, for example, had aligned her units of measure with the royal units of France.[15] and Peter the Great aligned the Russian units of measure with those of England.[16] In 1783 the British inventor James Watt, who was having difficulties in communicating with German scientists, called for the creation of a global decimal measurement system, proposing a system which used the density of water to link length and mass,[14] and in 1788 the French chemist Antoine Lavoisier commissioned a set of nine brass cylinders (a [French] pound and decimal subdivisions thereof) for his experimental work.[7]:71

In 1790, a proposal floated by the French to Britain and the United States, to establish a uniform measure of length, a metre based on the period of a pendulum with a beat of one second, was defeated in the British Parliament and United States Congress. The underlying issue was failure to agree on the latitude for the definition, since gravitational acceleration, and therefore the length of the pendulum, varies (inter alia) with latitude: each party wanted a definition according to a major latitude passing through their own country. The direct consequences of the failure were the French unilateral development and deployment of the metric system and its spread by trade to the continent; the British adoption of the Imperial System of Measures throughout the realm in 1824; and the United States' retention of the British common system of measures in place at the time of the independence of the colonies. This was the position that continued for nearly the next 200 years.[Note 6]

Implementation in Revolutionary France

Weights and measures of the Ancien Régime

It has been estimated that on the eve of the Revolution in 1789, the eight hundred or so units of measure in use in France had up to a quarter of a million different definitions because the quantity associated with each unit could differ from town to town, and even from trade to trade.[8]:2–3 Although certain standards, such as the pied du roi (the King's foot) had a degree of pre-eminence and were used by scientists, many traders chose to use their own measuring devices, giving scope for fraud and hindering commerce and industry.[17] These variations were promoted by local vested interests, but hindered trade and taxation.[18][19]

The units of weight and length

In 1790, a panel of five leading French scientists was appointed by the Académie des sciences to investigate weights and measures. They were Jean-Charles de Borda, Joseph-Louis Lagrange, Pierre-Simon Laplace, Gaspard Monge and Nicolas de Condorcet.[8]:2–3[20]:46 Over the following year, the panel, after studying various alternatives, made a series of recommendations regarding a new system of weights and measures, including that it should have a decimal radix, that the unit of length should be based on a fractional arc of a quadrant of the Earth's meridian, and that the unit of weight should be that of a cube of water whose dimension was a decimal fraction of the unit of length.[21][22][7]:50–51[23][24] The proposals were accepted by the French Assembly on 30 March 1791.[25]

Following acceptance, the Académie des sciences was instructed to implement the proposals. The Académie broke the tasks into five operations, allocating each part to a separate working group:[7]:82

- Measuring the difference in latitude between Dunkirk and Barcelona and triangulating between them

- Measuring the baselines used for the survey

- Verifying the length of the second pendulum at 45° latitude.

- Verifying the weight in a vacuum of a given volume of distilled water.

- Publishing conversion tables relating the new units of measure to the existing units of measure.

The panel decided that the new measure of length should be equal to one ten-millionth of the distance from the North Pole to the Equator (the quadrant of the Earth's circumference), measured along the meridian passing through Paris.[18]

Using Jean Picard's survey of 1670 and Jacques Cassini's survey of 1718, a provisional value of 443.44 lignes was assigned to the metre which, in turn, defined the other units of measure.[8]:106

While Méchain and Delambre were completing their survey, the commission had ordered a series of platinum bars to be made based on the provisional metre. When the final result was known, the bar whose length was closest to the meridional definition of the metre would be selected.

After 1792 the name of the original defined unit of mass, "gramme", which was too small to serve as a practical realisation for many purposes, was adopted, the new prefix "kilo" was added to it to form the name "kilogramme". Consequently, the kilogram is the only SI base unit that has an SI prefix as part of its unit name. A provisional kilogram standard was made and work was commissioned to determine the precise mass of a cubic decimetre (later to be defined as equal to one litre) of water. The regulation of trade and commerce required a "practical realisation": a single-piece, metallic reference standard that was one thousand times more massive that would be known as the grave.[Note 8] This mass unit defined by Lavoisier and René Just Haüy had been in use since 1793.[26] This new, practical realisation would ultimately become the base unit of mass. On 7 April 1795, the gramme, upon which the kilogram is based, was decreed to be equal to "the absolute weight of a volume of pure water equal to a cube of one hundredth of a metre, and at the temperature of the melting ice".[24] Although the definition of the kilogramme specified water at 0 °C – a highly stable temperature point – it was replaced with the temperature at which water reaches maximum density. This temperature, about 4 °C, was not accurately known, but one of the advantages of the new definition was that the precise Celsius value of the temperature was not actually important.[27][Note 9] The final conclusion was that one cubic decimetre of water at its maximum density was equal to 99.92072% of the mass of the provisional kilogram.[30]

On 7 April 1795 the metric system was formally defined in French law.[Note 10] It defined six new decimal units:[24]

- The mètre, for length – defined as one ten-millionth of the distance between the North Pole and the Equator through Paris

- The are (100 m2) for area [of land]

- The stère (1 m3) for volume of firewood

- The litre (1 dm3) for volumes of liquid

- The gramme, for mass – defined as the mass of one cubic centimetre of water

- The franc, for currency.

- Historical note: only the metre and (kilo)gramme defined here went on to become part of later metric systems.

Decimal multiples of these units were defined by Greek prefixes: "myria-" (10,000), "kilo-" (1000), "hecto-" (100) and "deka-" (10) and submultiples were defined by the Latin prefixes "deci-" (0.1), "centi-" (0.01) and "milli-" (0.001).[31]

The 1795 draft definitions enabled provisional copies of the kilograms and metres to be constructed.[32][33]

Meridional survey

The task of surveying the meridian arc, which was estimated to take two years, fell to Pierre Méchain and Jean-Baptiste Delambre. The task eventually took more than six years (1792–1798) with delays caused not only by unforeseen technical difficulties but also by the convulsed period of the aftermath of the Revolution.[8] Apart from the obvious nationalistic considerations, the Paris meridian was also a sound choice for practical scientific reasons: a portion of the quadrant from Dunkirk to Barcelona (about 1000 km, or one-tenth of the total) could be surveyed with start- and end-points at sea level, and that portion was roughly in the middle of the quadrant, where the effects of the Earth's oblateness were expected to be the largest.[18]

The project was split into two parts – the northern section of 742.7 km from the Belfry, Dunkirk to Rodez Cathedral which was surveyed by Delambre and the southern section of 333.0 km from Rodez to the Montjuïc Fortress, Barcelona which was surveyed by Méchain.[8]:227–230[Note 11]

Delambre used a baseline of about 10 km in length along a straight road, located close to Melun. In an operation taking six weeks, the baseline was accurately measured using four platinum rods, each of length two toises (about 3.9 m).[8]:227–230 Thereafter he used, where possible, the triangulation points used by Cassini in his 1744 survey of France. Méchain's baseline, of a similar length, and also on a straight section of road was in the Perpignan area.[8]:240–241 Although Méchain's sector was half the length of Delambre, it included the Pyrenees and hitherto unsurveyed parts of Spain. After the two surveyors met, each computed the other's baseline in order to cross-check their results and they then recomputed the metre as 443.296 lignes,[18][Note 12] notably shorter than the 1795 provisional value of 443.44 lignes On 15 November 1798 Delambre and Méchain returned to Paris with their data, having completed the survey. The final value of the mètre was defined in 1799 as the computed value from the survey.

- Historical note: It soon became apparent that Méchain and Delambre's result (443.296 lignes) was slightly too short for the meridional definition of the metre. Méchain had made a small error measuring the latitude of Barcelona, so he remeasured it, but kept the second set of measurements secret.[Note 13]

The French metric system

In June 1799, platinum prototypes were fabricated according to the measured quantities, the mètre des archives defined to be a length of 443.296 lignes, and the kilogramme des archives defined to be a weight of 18827.15 grains, and entered into the French National Archives. In December of that year, the metric system based on them became by law the sole system of weights and measures in France from 1801 until 1812.

Despite the law, the populace continued to use the old measures. In 1812, Napoleon revoked the law and issued one called the mesures usuelles, restoring the names and quantities of the customary measures but redefined as round multiples of the metric units, so it was a kind of hybrid system. In 1837, after the collapse of the Napoleonic Empire, the new Assembly reimposed the metric system defined by the laws of 1795 and 1799, to take effect in 1840. The metrication of France took until about 1858 to be completed. Some of the old unit names, especially the livre, originally a unit of mass derived from the Roman libra (as was the English pound), but now meaning 500 grams, are still in use today.

Development of non-coherent metric systems

At the start of the nineteenth century, the French Academy of Sciences' artefacts for length and mass were the only nascent units of the metric system that were defined in terms of formal standards. Other units based on them, except the litre proved to be short-lived. Pendulum clocks that could keep time in seconds had been in use for about 150 years, but their geometries were local to both latitude and altitude, so there was no standard of timekeeping. Nor had a unit of time been recognised as an essential base unit for the derivation of things like force and acceleration. Some quantities of electricity like charge and potential had been identified, but names and interrelationships of units were not yet established.[Note 14] Both Fahrenheit (~1724) and Celsius (~1742) scales of temperature existed, and varied instruments for measuring units or degrees of them. The base/derived unit model had not yet been elaborated, nor was it known how many physical quantities might be inter-related.

A model of interrelated units was first proposed in 1861 by the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BAAS) based on what came to be called the "mechanical" units (length, mass and time). Over the following decades, this foundation enabled mechanical, electrical and thermal units to be correlated.

Time

In 1832 German mathematician Carl-Friedrich Gauss made the first absolute measurements of the Earth's magnetic field using a decimal system based on the use of the millimetre, milligram, and second as the base unit of time.[34]:109 Gauss' second was based on astronomical observations of the rotation of the Earth, and was the sexagesimal second of the ancients: a partitioning of the solar day into two cycles of 12 periods, and each period divided into 60 intervals, and each interval so divided again, so that a second was 1/86,400th of the day.[Note 15] This effectively established a time dimension as a necessary constituent of any useful system of measures, and the astronomical second as the base unit.

Work and energy

.png)

In a paper published in 1843, James Prescott Joule first demonstrated a means of measuring the energy transferred between different systems when work is done thereby relating Nicolas Clément's calorie, defined in 1824 as "the amount of heat required to raise the temperature of 1 kg of water from 0 to 1 °C at 1 atmosphere of pressure" to mechanical work.[35][36] Energy became the unifying concept of nineteenth century science,[37] initially by bringing thermodynamics and mechanics together and later adding electrical technology.

The first structured metric system: CGS

In 1861 a committee of the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BAAS) including William Thomson (later Lord Kelvin), James Clerk Maxwell and James Prescott Joule among its members was tasked with investigating the "Standards of Electrical Resistance". In their first report (1862)[38] they laid the ground rules for their work – the metric system was to be used, measures of electrical energy must have the same units as measures of mechanical energy and two sets of electromagnetic units would have to be derived – an electromagnetic system and an electrostatic system. In the second report (1863)[39] they introduced the concept of a coherent system of units whereby units of length, mass and time were identified as "fundamental units" (now known as base units). All other units of measure could be derived (hence derived units) from these base units. The metre, gram and second were chosen as base units.[40][41]

In 1861, before a meeting of the BAAS, Charles Bright and Latimer Clark proposed the names of ohm, volt, and farad in honour of Georg Ohm, Alessandro Volta and Michael Faraday respectively for the practical units based on the CGS absolute system. This was supported by Thomson (Lord Kelvin).[42] The concept of naming units of measure after noteworthy scientists was subsequently used for other units.

In 1873, another committee of the BAAS (which also included Maxwell and Thomson) tasked with "the Selection and Nomenclature of Dynamical and Electrical Units" recommended using the cgs system of units. The committee also recommended the names of "dyne" and "erg" for the cgs units of force and energy.[43][41][44] The cgs system became the basis for scientific work for the next seventy years.

The reports recognised two centimetre–gram–second based systems for electrical units: the Electromagnetic (or absolute) system of units (EMU) and the Electrostatic system of units (ESU).

Electrical units

In the 1820s Georg Ohm formulated Ohm's Law, which can be extended to relate power to current, electric potential (voltage) and resistance.[45][46] During the following decades the realisation of a coherent system of units that incorporated the measurement of electromagnetic phenomena and Ohm's law was beset with problems – several different systems of units were devised.

| Symbols | Meaning |

|---|---|

| electromagnetic and electrostatic forces | |

| electric currents in conductors | |

| electrical charges | |

| conductor length | |

| distance between charges/conductors | |

| electric constant[Note 16] | |

| magnetic constant[Note 16] | |

| constants of proportionality | |

| speed of light[47] | |

| steradians surrounding a point[Note 17] | |

| electric power | |

| electric potential | |

| electric current | |

| energy | |

| electric charge | |

| dimensions: mass, length, time |

- Electromagnetic (absolute) system of units (EMU)

- The Electromagnetic system of units (EMU) was developed from André-Marie Ampère's discovery in the 1820s of a relationship between currents in two conductors and the force between them now known as Ampere's law:

- where (SI units)

- In 1833 Gauss pointed out the possibility of equating this force with its mechanical equivalent. This proposal received further support from Wilhelm Weber in 1851.[48] In this system, current is defined by setting the magnetic force constant to unity and electric potential is defined in such a way as to ensure the unit of power calculated by the relation is an erg/second. The electromagnetic units of measure were known as the abampere, abvolt, and so on.[49] These units were later scaled for use in the International System.[50]

- Electrostatic system of units (ESU)

- The Electrostatic system of units (ESU) was based on Coulomb's quantification in 1783 of the force acting between two charged bodies. This relationship, now known as Coulomb's law can be written

- where (SI units)

- In this system, the unit for charge is defined by setting the Coulomb force constant () to unity and the unit for electric potential was defined to ensure the unit of energy calculated by the relation is one erg. The electrostatic units of measure were the statampere, statvolt, and so on.[51]

- Gaussian system of units

- The Gaussian system of units was based on Heinrich Hertz's realisation while verifying Maxwell's equations in 1888, that the electromagnetic and electrostatic units were related by:

- Using this relationship, he proposed merging the EMU and the ESU systems into one system using the EMU units for magnetic quantities (subsequently named the gauss and maxwell) and ESU units elsewhere. He named this combined set of units "Gaussian units". This set of units has been recognised as being particularly useful in theoretical physics.[34]:128

- Quad–eleventhgram–second (QES) or International system of units

- The CGS units of measure used in scientific work were not practical for engineering, leading to the development of a more applicable system of electric units especially for telegraphy. The unit of length was 107 m (approx. the length of the Earth's quadrant), the unit of mass was an unnamed unit equal to 10−11 g and the unit of time was the second. The units of mass and length were scaled incongruously to yield more consistent and usable electric units in terms of mechanical measures. Informally called the "practical" system, it was properly termed the quad–eleventhgram–second (QES) system of units according to convention.

- The definitions of electrical units incorporated the magnetic constant like the EMU system, and the names of the units were carried over from that system, but scaled according to the defined mechanical units.[54] The system was formalised as the International system late in the 19th century and its units later designated the "international ampere", "international volt", etc.[55]:155–156

- Heaviside–Lorentz system of units

- The factor that occurs in Maxwell's equations in the gaussian system (and the other CGS systems) is related to that there are steradians surrounding a point, such as a point electric charge. This factor could be eliminated from contexts that do not involve spherical coordinates by incorporating the factor into the definitions of the quantities involved. The system was proposed by Oliver Heaviside in 1883 and is also known as the "rationalised gaussian system of units". The SI later adopted rationalised units according to the gaussian rationalisation scheme.

In the three CGS systems, the constants and and consequently and were dimensionless, and thus did not require any units to define them.

The electrical units of measure did not easily fit into the coherent system of mechanical units defined by the BAAS. Using dimensional analysis, the dimensions of voltage in the ESU system were identical to the dimensions of current in the EMU system, while resistance had dimensions of velocity in the EMU system, but the inverse of velocity in the ESU system.[41]

Thermodynamics

Maxwell and Boltzmann had produced theories describing the inter-relational of temperature, pressure and volume of a gas on a microscopic scale but otherwise, in 1900, there was no understanding of the microscopic nature of temperature.[56][57]

By the end of the nineteenth century, the fundamental macroscopic laws of thermodynamics had been formulated and although techniques existed to measure temperature using empirical techniques, the scientific understanding of the nature of temperature was minimal.

Convention of the metre

With increasing international adoption of the metre, the shortcomings of the mètre des Archives as a standard became ever more apparent. Countries which adopted the metre as a legal measure purchased standard metre bars that were intended to be equal in length to the mètre des Archives, but there was no systematic way of ensuring that the countries were actually working to the same standard. The meridional definition, which had been intended to ensure international reproducibility, quickly proved so impractical that it was all but abandoned in favour of the artefact standards, but the mètre des Archives (and most of its copies) were "end standards": such standards (bars which are exactly one metre in length) are prone to wear with use, and different standard bars could be expected to wear at different rates.[58]

In 1867, it was proposed that a new international standard metre be created, and the length was taken to be that of the mètre des Archives "in the state in which it shall be found".[59][60] The International Conference on Geodesy in 1867 called for the creation of a new international prototype of the metre[59][60][Note 18] and of a system by which national standards could be compared with it. The international prototype would also be a "line standard", that is the metre was defined as the distance between two lines marked on the bar, so avoiding the wear problems of end standards. The French government gave practical support to the creation of an International Metre Commission, which met in Paris in 1870 and again in 1872 with the participation of about thirty countries.[59]

On 20 May 1875 an international treaty known as the Convention du Mètre (Metre Convention) was signed by 17 states.[19][61] This treaty established the following organisations to conduct international activities relating to a uniform system for measurements:

- Conférence générale des poids et mesures (CGPM or General Conference on Weights and Measures), an intergovernmental conference of official delegates of member nations and the supreme authority for all actions;

- Comité international des poids et mesures (CIPM or International Committee for Weights and Measures), consisting of selected scientists and metrologists, which prepares and executes the decisions of the CGPM and is responsible for the supervision of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures;

- Bureau international des poids et mesures (BIPM or International Bureau of Weights and Measures), a permanent laboratory and world centre of scientific metrology, the activities of which include the establishment of the basic standards and scales of the principal physical quantities, maintenance of the international prototype standards and oversight of regular comparisons between the international prototype and the various national standards.

The international prototype of the metre and international prototype of the kilogram were both made from a 90% platinum, 10% iridium alloy which is exceptionally hard and which has good electrical and thermal conductivity properties. The prototype had a special X-shaped (Tresca) cross section to minimise the effects of torsional strain during length comparisons.[19] and the prototype kilograms were cylindrical in shape. The London firm Johnson Matthey delivered 30 prototype metres and 40 prototype kilograms. At the first meeting of the CGPM in 1889 bar No. 6 and cylinder No. X were accepted as the international prototypes. The remainder were either kept as BIPM working copies or distributed to member states as national prototypes.[62]

Following the Convention of the Metre, in 1889 the BIPM had custody of two artefacts – one to define length and the other to define mass. Other units of measure which did not rely on specific artefacts were controlled by other bodies.

Although the definition of the kilogram remained unchanged throughout the 20th century, the 3rd CGPM in 1901 clarified that the kilogram was a unit of mass, not of weight. The original batch of 40 prototypes (adopted in 1889) were supplemented from time to time with further prototypes for use by new signatories to the Metre Convention.[63]

In 1921 the Treaty of the Metre was extended to cover electrical units, with the CGPM merging its work with that of the IEC.

Measurement systems before World War II

The 20th century history of measurement is marked by five periods: the 1901 definition of the coherent MKS system; the intervening 50 years of coexistence of the MKS, cgs and common systems of measures; the 1948 Practical system of units prototype of the SI; the introduction of the SI in 1960; and the evolution of the SI in the latter half century.

A coherent system

The need for an independent electromagnetic dimension to resolve the difficulties related to defining such units in terms of length, mass and time was identified by Giorgi in 1901. This led to Giorgi presenting a paper in October 1901 to the congress of the Associazione Elettrotecnica Italiana (A.E.I.)[64] in which he showed that a coherent electro-mechanical system of units could be obtained by adding a fourth base unit of an electrical nature (e.g. ampere, volt or ohm) to the three base units proposed in the 1861 BAAS report. This gave physical dimensions to the constants ke and km and hence also to the electro-mechanical quantities ε0 (permittivity of free space) and μ0 (permeability of free space).[65] His work also recognised the relevance of energy in the establishment of a coherent, rational system of units, with the joule as the unit of energy, and the electrical units in the International system of units remaining unchanged.[55]:156 However it took more than thirty years before Giorgi's work was accepted in practice by the IEC.

Systems of measurement in the industrial era

As industry developed around the world, the cgs system of units as adopted by the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1873 with its plethora of electrical units continued to be the dominant system of measurement, and remained so for at least the next 60 years. The advantages were several: it had a comprehensive set of derived units which, while not quite coherent, were at least homologous; the MKS system lacked a defined unit of electromagnetism at all; the MKS units were inconveniently large for the sciences; customary systems of measures held sway in the United States, Britain and the British empire, and even to some extent in France, the birthplace of the metric system, which inhibited adoption of any competing system. Finally, war, nationalism and other political forces inhibited development of the science favouring a coherent system of units.

At the 8th CGPM in 1933 the need to replace the "International" electrical units with "absolute" units was raised. The IEC proposal that Giorgi's 'system', denoted informally as MKSX, be adopted was accepted, but no decision was made as to which electrical unit should be the fourth base unit. In 1935 J E Sears[66], proposed that this should be the ampere, but World War II prevented this being formalised until 1946.

The first (and only) follow-up comparison of the national standards with the international prototype of the metre was carried out between 1921 and 1936,[19][60] and indicated that the definition of the metre was preserved to within 0.2 µm.[67] During this follow-up comparison, the way in which the prototype metre should be measured was more clearly defined—the 1889 definition had defined the metre as being the length of the prototype at the temperature of melting ice, but in 1927 the 7th CGPM extended this definition to specify that the prototype metre shall be "supported on two cylinders of at least one centimetre diameter, symmetrically placed in the same horizontal plane at a distance of 571 mm from each other".[34]:142–43,148 The choice of 571 mm represents the Airy points of the prototype—the points at which the bending or droop of the bar is minimised.[68]

Working draft of SI: Practical system of units

The 9th CGPM met in 1948, fifteen years after the 8th CGPM. In response to formal requests made by the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics and by the French government to establish a practical system of units of measure, the CGPM requested the CIPM to prepare recommendations for a single practical system of units of measurement, suitable for adoption by all countries adhering to the Metre Convention.[69] The CIPM's draft proposal was an extensive revision and simplification of the metric unit definitions, symbols and terminology based on the MKS system of units.

In accordance with astronomical observations, the second was set as a fraction of the year 1900. The electromagnetic base unit as required by Giorgi was accepted as the ampere. After negotiations with the CIS and IUPAP, two further units, the degree kelvin and the candela, were also proposed as base units.[70] For the first time the CGPM made recommendations concerning derived units. At the same time the CGPM adopted conventions for the writing and printing of unit symbols and numbers and catalogued the symbols for the most important MKS and CGS units of measure.[71]

Time

Until the advent of the atomic clock, the most reliable timekeeper available to mankind was the Earth's rotation. It was natural therefore that the astronomers under the auspices of the International Astronomical Union (IAU) took the lead in maintaining the standards relating to time. During the 20th century it became apparent that the Earth's rotation was slowing down, resulting in days becoming 1.4 milliseconds longer each century[72] – this was verified by comparing the calculated timings of eclipses of the Sun with those observed in antiquity going back to Chinese records of 763 BC.[73] In 1956 the 10th CGPM instructed the CIPM to prepare a definition of the second; in 1958 the definition was published stating that the second (called an ephemeris second) would be calculated by extrapolation using Earth's rotational speed in 1900.[72]

Electrical unit

In accordance with Giorgi's proposals of 1901, the CIPM also recommended that the ampere be the base unit from which electromechanical units would be derived. The definitions for the ohm and volt that had previously been in use were discarded and these units became derived units based on the ampere. In 1946 the CIPM formally adopted a definition of the ampere based on the original EMU definition, and redefined the ohm in terms of other base units.[74] The definitions for absolute electrical system based on the ampere were formalised in 1948.[75] The draft proposed units with these names are very close, but not identical, to the International units.[76]

Temperature

In the Celsius scale from the 18th century, temperature was expressed in degrees Celsius with the definition that ice melted at 0 °C, and at standard atmospheric pressure water boiled at 100 °C. A series of lookup tables defined temperature in terms of inter-related empirical measurements made using various devices. In 1948, definitions relating to temperature had to be clarified. (The degree, as an angular measure, was adopted for general use in a number of countries, so in 1948 the General Conference on Weights and Measures (CGPM) recommended that the degree Celsius, as used for the measurement of temperature, be renamed the degree Celsius.)[77]

At the 9th CGPM, the Celsius temperature scale was renamed the Celsius scale and the scale itself was fixed by defining the triple point of water as 0.01 °C,[78] though the CGPM left the formal definition of absolute zero until the 10th CGPM when the name "Kelvin" was assigned to the absolute temperature scale, and the triple point of water was defined as being 273.16 °K.[79]

Luminosity

Prior to 1937, the International Commission on Illumination (CIE from its French title, the Commission Internationale de l'Eclairage) in conjunction with the CIPM produced a standard for luminous intensity to replace the various national standards. This standard, the candela (cd) which was defined as "the brightness of the full radiator at the temperature of solidification of platinum is 60 new candles per square centimetre"[80] was ratified by the CGPM in 1948.

Derived units

The newly accepted definition of the ampere allowed practical and useful coherent definitions of a set of electromagnetic derived units including farad, henry, watt, tesla, weber, volt, ohm, and coulomb. Two derived units, lux and lumen, were based on the new candela, and one, degree Celsius, equivalent to the degree Kelvin. Five other miscellaneous derived units completed the draft proposal: radian, steradian, hertz, joule and newton.

International System of Units (SI)

In 1952 the CIPM proposed the use of wavelength of a specific light source as the standard for defining length, and in 1960 the CGPM accepted this proposal using radiation corresponding to a transition between specified energy levels of the krypton 86 atom as the new standard for the metre. The standard metre artefact was retired.

In 1960, Giorgi's proposals were adopted as the basis of the Système International d'Unités (International System of Units), the SI.[34]:109 This initial definition of the SI included six base units, the metre, kilogram, second, ampere, degree Kelvin and candela, and sixteen coherent derived units.[81]

Evolution of the modern SI

The evolution of the SI after its publication in 1960 has seen the addition of a seventh base unit, the mole, and six more derived units, the pascal for pressure, the gray, sievert and becquerel for radiation, the siemens for electrical conductance, and katal for catalytic (enzymatic) activity. Several units have also been redefined in terms of physical constants.

New base and derived units

Over the ensuing years, the BIPM developed and maintained cross-correlations relating various measuring devices such as thermocouples, light spectra and the like to the equivalent temperatures.[82]

The mole was originally known as a gram-atom or a gram-molecule – the amount of a substance measured in grams divided by its atomic weight. Originally chemists and physicists had differing views regarding the definition of the atomic weight – both assigned a value of 16 atomic mass units (amu) to oxygen, but physicists defined oxygen in terms of the 16O isotope whereas chemists assigned 16 amu to 16O, 17O and 18O isotopes mixed in the proportion that they occur in nature. Finally an agreement between the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics[83] (IUPAP) and the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) brought this duality to an end in 1959/60, both parties agreeing to define the atomic weight of 12C as being exactly 12 amu. This agreement was confirmed by ISO and in 1969 the CIPM recommended its inclusion in SI as a base unit. This was done in 1971 at the 14th CGPM.[34]:114–115

Start of migration to constant definitions

The second major trend in the post-modern SI was the migration of unit definitions in terms of physical constants of nature.

In 1967, at the 13th CGPM the degree Kelvin (°K) was renamed the "kelvin" (K).[84]

Astronomers from the US Naval Observatory (USNO) and the National Physical Laboratory determined a relationship between the frequency of radiation corresponding to the transition between the two hyperfine levels of the ground state of the caesium 133 atom and the estimated rate of rotation of the earth in 1900. Their atomic definition of the second was adopted in 1968 by the 13th CGPM.

By 1975, when the second had been defined in terms of a physical phenomenon rather than the earth's rotation, the CGPM authorised the CIPM to investigate the use of the speed of light as the basis for the definition of the metre. This proposal was accepted in 1983.[85]

The candela definition proved difficult to implement so in 1979, the definition was revised and the reference to the radiation source was replaced by defining the candela in terms of the power of a specified frequency of monochromatic yellowish-green visible light,[34]:115 which is close to the frequency where the human eye, when adapted to bright conditions, has greatest sensitivity.

Kilogram artefact instability

After the metre was redefined in 1960, the kilogram remained the only SI base defined by a physical artefact. During the years that followed the definitions of the base units and particularly the mise en pratique[87] to realise these definitions have been refined.

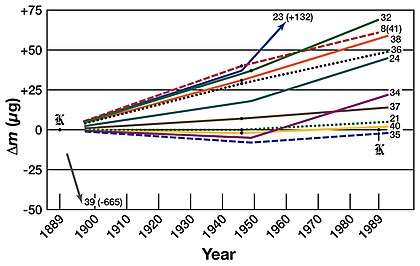

The third periodic recalibration in 1988–1989 revealed that the average difference between the IPK and adjusted baseline for the national prototypes was 50 μg – in 1889 the baseline of the national prototypes had been adjusted so that the difference was zero. As the IPK is the definitive kilogram, there is no way of telling whether the IPK had been losing mass or the national prototypes had been gaining mass.[86]

During the course of the century, the various national prototypes of the kilogram were recalibrated against the international prototype of the kilogram (IPK) and therefore against each other. The initial 1889 starting-value offsets of the national prototypes relative to the IPK were nulled,[86] with any subsequent mass changes being relative to the IPK.

Proposed replacements for the IPK

A number of replacements were proposed for the IPK.

From the early 1990s, the International Avogadro Project worked on creating a 1 kilogram, 94 mm, sphere made of a uniform silicon-28 crystal, with the intention of being able replace the IPK with a physical object which would be precisely reproducible from an exact specification. Due to its precise construction, the Avogadro Project's sphere is likely to be the most precisely spherical object ever created by humans.[88]

Other groups worked on concepts such as creating a reference mass via precise electrodeposition of gold or bismuth atoms, and defining the kilogram in terms of the ampere by relating it to forces generated by electromagnetic repulsion of electric currents.[89]

Eventually, the choices were narrowed down to the use of the Watt balance and the International Avogadro Project sphere.[89]

Ultimately, a decision was made not to create any physical replacement for the IPK, but instead to define all SI units in terms of assigning precise values to a number of physical constants which had previously been measured in terms of the earlier unit definitions.

Redefinition in terms of fundamental constants

At its 23rd meeting (2007), the CGPM mandated the CIPM to investigate the use of natural constants as the basis for all units of measure rather than the artefacts that were then in use.

The following year this was endorsed by the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics (IUPAP).[90] At a meeting of the CCU held in Reading, United Kingdom, in September 2010, a resolution[91] and draft changes to the SI brochure that were to be presented to the next meeting of the CIPM in October 2010 were agreed in principle.[92] The CIPM meeting of October 2010 found that "the conditions set by the General Conference at its 23rd meeting have not yet been fully met.[Note 20] For this reason the CIPM does not propose a revision of the SI at the present time".[94] The CIPM, however, presented a resolution for consideration at the 24th CGPM (17–21 October 2011) to agree to the new definitions in principle, but not to implement them until the details had been finalised.[95]

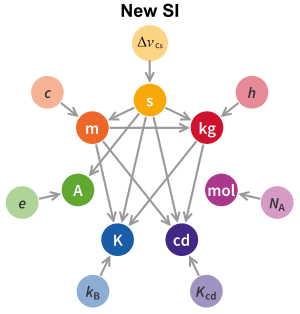

In the redefinition, four of the seven SI base units – the kilogram, ampere, kelvin, and mole – were redefined by setting exact numerical values for the Planck constant (h), the elementary electric charge (e), the Boltzmann constant (kB), and the Avogadro constant (NA), respectively. The second, metre, and candela were already defined by physical constants and were subject to correction to their definitions. The new definitions aimed to improve the SI without changing the value of any units, ensuring continuity with existing measurements.[96][97]

This resolution was accepted by the conference,[98] and in addition the CGPM moved the date of the 25th meeting forward from 2015 to 2014.[99][100] At the 25th meeting on 18 to 20 November 2014, it was found that "despite [progress in the necessary requirements] the data do not yet appear to be sufficiently robust for the CGPM to adopt the revised SI at its 25th meeting",[101] thus postponing the revision to the next meeting in 2018.

Measurements accurate enough to meet the conditions were available in 2017 and the redefinition[102] was adopted at the 26th CGPM (13–16 November 2018), with the changes finally coming into force in 2019, creating a system of definitions which is intended to be stable for the long term.

See also

Notes

- ratios of 1 between magnitudes of unit quantities

- just under 2 metres in today's units

- There were two beats in an oscillation.

- the pendulum would have had a length of 205.6 mm and the virgula was ~185.2 mm.

- The acceleration due to gravity at the poles is 9.832 m/s−2 and at the equator 9.780 m/s−2, a difference of about 0.5%. Archived 9 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Much of the British Empire except the UK adopted the metric system early on; the UK partly adopted the metric system late in the 20th century.

- Condorcet is universally misquoted as saying that "the metric system is for all people for all time." His remarks were probably between 1790 and 1792. The names 'metre' and 'metre-system' i.e. 'metric system' were not yet defined. Condorcet actually said, "measurement of an eternal and perfectly spherical earth is a measurement for all people for all time." He did not know what, if any, units of length or other measure would be derived from this. His political advocacy eventually resulted in him committing suicide rather than be executed by the Revolutionaries.

- from Latin gravitas: "weight"

- There were three reasons for the change from the freezing point to the point of maximum density:

1. It proved difficult to achieve the freezing point precisely. As van Swinden wrote in his report, whatever care citizens Lefévre-Gineau and Fabbroni took, by surrounding the vase that contained the water with a large quantity of crushed ice, and frequently renewing it, they never succeeded in lowering the centigrade thermometer below two-tenths of a degree; and the average water temperature during the course of their experiments was 3/10;[28]:168

2. This maximum of water density as a function of temperature can be detected ‘independent of temperature awareness’,[28]:170 that is, without having to know the precise numerical value of the temperature. Namely, as one weighs a submerged object, one notices that, as the temperature is lowered (and one can know that the temperature is going down without knowing precisely what the numerical value of the temperature is at any moment), the apparent weight goes down, reaches a minimum (that's the point of maximum density of water), and then goes back up. In the course of this process, the precise value of the temperature is of no interest and the maximum of density is determined directly by the weighing, as opposed to by measuring the temperature of the water and making sure it maches some predetermined value. The advantage is both practical and conceptual. On the practical side, precision thermometry is difficult, and this procedure makes it unnecessary. On the conceptual side, the procedure makes the definition of the unit of mass completely independent from the definition of a temperature scale.

3. The point of maximum density is also the point where the density depends the least on small changes in temperature.[29]:563–564 This is a general mathematical fact: if a function f(·) of a variable x is sufficiently free of discontinuities, then, if one plots f vs. x, and looks at a point (xmax, f(xmax)) at which f has a ‘peak’ (meaning, f decreases no matter whether x is made a bit larger or a bit smaller than xmax), once notices that f is ‘flat’ at xmax—the tangent line to it at that point is horizontal, so the slope of f at xmax is zero. This is why f changes little from its maximum value if x is made slightly different from xmax. - Article 5 of the law of 18 Germinal, Year III

- Distances measured using Google Earth. The coordinates are:

51°02′08″N 2°22′34″E – Belfry, Dunkirk

44°25′57″N 2°34′24″E – Rodez Cathedral

41°21′48″N 2°10′01″E – Montjuïc, Barcelona - All values in lignes are referred to the toise de Pérou, not to the later value in mesures usuelles. 1 toise = 6 pieds; 1 pied = 12 pouces; 1 pouce = 12 lignes; so 1 toise = 864 lignes.

- The modern value, for the WGS 84 reference spheroid of 1.000 196 57 m is 443.383 08 lignes.

- Ohm's Law wasn't discovered until 1824, for example.

- It is certain, however, that 170 years after the invention of pendulum clocks, that Gauss had sufficiently accurate mechanical clocks for his work.

- The electric constant, termed the permittivity of free space (a vacuum, such as might be found in a vacuum tube) is a physical electric constant with units farads/metre that represents the ability of a vacuum to support an electric field.

The magnetic constant termed the permeability of free space is a physical magnetic constant with units henries/metre that represents the ability of a vacuum to support a magnetic field. Iron, for example, has both high permittivity because it readily conducts electricity and high permeability because it makes a good magnet. A vacuum does not "conduct" electricity very well, nor can it be easily "magnetised", so the electric and magnetic constants of a vacuum are tiny. - This factor appears in Maxwell's equations and represents the fact that electric and magnetic fields may be considered as point quantities that propagate equally in all directions, i.e. spherically

- The term "prototype" does not imply that it was the first in a series and that other standard metres would come after it: the "prototype" of the metre was the one that came first in the logical chain of comparisons, that is the metre to which all other standards were compared.

- Prototype No. 8(41) was accidentally stamped with the number 41, but its accessories carry the proper number 8. Since there is no prototype marked 8, this prototype is referred to as 8(41).

- In particular the CIPM was to prepare a detailed mise en pratique for each of the new definitions of the kilogram, ampere, kelvin and mole set by the 23rd CGPM.[93]

References

- "English translation of Magna Carta". British Library. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- Durham, John W (2 December 1992). "The Introduction of "Arabic" Numerals in Euiropean Accounting". The Accounting Historians Journal. The Academy of Accounting Historians. 19 (2): 27–28. doi:10.2308/0148-4184.19.2.25. JSTOR 40698081.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. (January 2001), "The Arabic numeral system", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. (October 1998), "Leonardo Pisano Fibonacci", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. (January 2004), "Simon Stevin", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. (October 2005), "The real numbers: Pythagoras to Stevin", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- Tavernor, Robert (2007). Smoot's Ear: The Measure of Humanity. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12492-7.

- Alder (2004). The Measure of all Things – The Seven-Year-Odyssey that Transformed the World. ISBN 978-0-349-11507-8.

- Zupko, Ronald Edward (1990). Revolution in Measurement: Western European Weights and Measures Since the Age of Science. Memoirs of the American Philosophical Society, Volume 186. Philadelphia. pp. 123–129. ISBN 978-0-87169-186-6.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. (June 2004), "Gabriel Mouton", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- G. Bigourdan (1901). "Le système métrique des poids et des mesures" [The metric system of weights and measures] (in French). Paris. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

On voit que le projet de Mouton est, sans aucune différence de principe, celui qui a ét réalisé par notre Système métrique. [It can be seen that Mouton's proposal was, in principle, no different to the metric system as we know it.]

- Taton, R; Wilson, C, eds. (1989). Planetary astronomy from the Renaissance to the rise of astrophysics – Part A: tycho Brahe to Newton. Cambridge University Press. p. 269. ISBN 978-0-521-24254-7.

- Snyder, John P (1993). Flattening the earth : two thousand years of map projections. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-226-76747-5.

- Carnegie, Andrew (May 1905). James Watt (PDF). Doubleday, Page & Company. pp. 59–60. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- Loidi, Juan Navarro; Saenz, Pilar Merino (6–9 September 2006). "The units of length in the Spanish treatises of military engineering" (PDF). The Global and the Local: The History of Science and the Cultural Integration of Europe. Proceedings of the 2nd ICESHS. Cracow, Poland: The Press of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- Jackson, Lowis D'Aguilar. Modern metrology; a manual of the metrical units and systems of the present century (1882). London: C Lockwood and co. p. 11. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- "History of measurement". Laboratoire national de métrologie et d'essais (LNE) (Métrologie française). Retrieved 6 February 2011.

-

- Nelson, Robert A. (1981), "Foundations of the international system of units (SI)" (PDF), Physics Teacher, 19 (9): 597, Bibcode:1981PhTea..19..596N, doi:10.1119/1.2340901

- Konvitz, Josef (1987). Cartography in France, 1660–1848: Science, Engineering, and Statecraft. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-45094-0.

- Hellman, C. Doris (January 1936). "Legendre and the French Reform of Weights and Measures". Osiris. University of Chicago Press. 1: 314–340. doi:10.1086/368429. JSTOR 301613.

- Glaser, Anton (1981) [1971]. History of Binary and other Nondecimal Numeration (PDF) (Revised ed.). Tomash. pp. 71–72. ISBN 978-0-938228-00-4. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- Adams,John Quincy (22 February 1821). Report upon Weights and Measures. Washington DC: Office of the Secretary of State of the United States.

- "Décret relatif aux poids et aux mesures. 18 germinal an 3 (7 avril 1795)" [Decree regarding weights and measures: 18 Germinal Year III (7 April 1795)]. Le systeme metrique decimal (in French). Association Métrodiff. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- "Lois et décrets" [Laws and decrees]. Histoire de la métrologie (in French). Paris: Association Métrodiff. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- Poirier, Jean-Pierre. "Chapter 8: Lavoisier, Arts and Trades". Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier (1743–1794 – Life and Works. Comité Lavoisier de l'Académie des Sciences de Paris. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- L'Histoire Du Mètre, La Détermination De L'Unité De Poids, link to Web site here. Archived 10 May 2013 at WebCite

- van Swinden, Jean Henri (1799) [Fructidor an 7 (Aug/Sep 1799)]. "Suite Du Rapport. Fait à l'Institut national des sciences et arts, le 29 prairial an 7, au non de la classe des sciences mathématiques et physiques. Sur la mesure de la méridienne de France , et les résultats qui en ont été déduits pour déterminer les bases du nouveau systéme métrique". Journal de Physique, de Chimie, 'd'Historie Naturelle at des Arts. VI (XLIX): 161–177.

- Trallès, M. (1810). "Rapport de M. Trallès a la Commission, sur l'unité de poids du système métrique décimal, d'après le travail de M. Lefèvre–Gineau, le 11 prairial an 7". In Méchain, Pierre; Delambre, Jean B. J. (eds.). Base du système métrique décimal, ou mesure de l'arc du méridien compris entre les parallèles de Dunkerque et Barcelone executée en 1792 et années suivantes: suite des Mémoires de l'Institut. 3. pp. 558–580.

- History of the kilogram Archived 21 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Coquebert, Ch (August 1797). "An account of the New System of measures established in France". A Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry, and the Arts. 1: 193–200.

- Suzanne Débarbat. "Fixation de la longueur définitive du mètre" [Establishing the definitive metre] (in French). Ministère de la culture et de la communication (French ministry of culture and communications). Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- Smeaton, William A. (2000). "The Foundation of the Metric System in France in the 1790s: The importance of Etienne Lenoir's platinum measuring instruments". Platinum Metals Rev. Ely, Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom. 44 (3): 125–134. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- International Bureau of Weights and Measures (2006), The International System of Units (SI) (PDF) (8th ed.), ISBN 92-822-2213-6, archived (PDF) from the original on 14 August 2017

- Hargrove, JL (December 2006). "History of the calorie in nutrition". Journal of Nutrition. Bethesda, Maryland. 136 (12): 2957–61. doi:10.1093/jn/136.12.2957. PMID 17116702.

- "Joule's was friction apparatus, 1843". London, York and Bradford: Science Museum, National Railway Museum and the National Media Museum. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- Kapil Subramanian (25 February 2011). "How the electric telegraph shaped electromagnetism" (PDF). Current Science. 100 (4). Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- Thomson, William; Joule, James Prescott; Maxwell, James Clerk; Jenkin, Flemming (1873). "First Report – Cambridge 3 October 1862". In Jenkin, Flemming (ed.). Reports on the Committee on Standards of Electrical Resistance – Appointed by the British Association for the Advancement of Science. London. pp. 1–3. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- Thomson, William; Joule, James Prescott; Maxwell, James Clerk; Jenkin, Flemming (1873). "Second report – Newcastle-upon-Tyne 26 August 1863". In Jenkin, Flemming (ed.). Reports on the Committee on Standards of Electrical Resistance – Appointed by the British Association for the Advancement of Science. London. pp. 39–41. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- J C Maxwell (1873). A treatise on electricity and magnetism. 1. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 1–3. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- J C Maxwell (1873). A treatise on electricity and magnetism. 2. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 242–245. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- Silvanus P. Thompson. "In the beginning ... Lord Kelvin". International Electrotechnical Commission. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- Professor Everett, ed. (1874). "First Report of the Committee for the Selection and Nomenclature of Dynamical and Electrical Units". Report on the Forty-third Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science Held at Bradford in September 1873. British Association for the Advancement of Science: 222–225. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- "centimeter–gram–second systems of units". Sizes, Inc. 6 August 2001. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. (January 2000), "Georg Simon Ohm", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- Booth, Graham (2003). Revise AS Physics. London: Letts Educational. Chapter 2 – Electricity. ISBN 184315-3025.

- A large constant, about 300,000,000 metres/second.

- "The International System of Units". Satellite Today. 1 February 2000. Archived from the original on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- Russ Rowlett (4 December 2008). "How Many? A Dictionary of Units of Measurement: "ab-"". University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- "farad". Sizes, Inc. 9 June 2007. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- Russ Rowlett (1 September 2004). "How Many? A Dictionary of Units of Measurement: "stat-"". University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- Dan Petru Danescu (9 January 2009). "The evolution of the Gaussian Units" (PDF). The general journal of science. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- "Gaussian, SI and Other Systems of Units in Electromagnetic Theory" (PDF). Physics 221A, Fall 2010, Appendix A. Berkeley: Department of Physics University of California. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- "1981 ... A year of anniversaries" (PDF). IEC Bulletin. Geneva: International Electrotechnical Commission. XV (67). January 1981. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- McGreevy, Thomas; Cunningham, Peter (1995). The Basis of Measurement: Volume 1 – Historical Aspects. Picton Publishing (Chippenham) Ltd. ISBN 978-0-948251-82-5.

(pg 140) The originator of the metric system might be said to be Gabriel Mouton.

- H.T.Pledge (1959) [1939]. "Chapter XXI: Quantum Theory". Science since 1500. Harper Torchbooks. pp. 271–275.

- Thomas W. Leland. G.A. Mansoori (ed.). "Basic Principles of Classical and Statistical Thermodynamics" (PDF). Department of Chemical Engineering, University of Illinois at Chicago. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

-

- The International Metre Commission (1870–1872), International Bureau of Weights and Measures, retrieved 15 August 2010

- The BIPM and the evolution of the definition of the metre, International Bureau of Weights and Measures, archived from the original on 7 June 2011, retrieved 15 August 2010

- Text of the treaty: "Convention du mètre" (PDF) (in French). Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- Jabbour, Z.J.; Yaniv, S.L. (2001). "The Kilogram and Measurements of Mass and Force" (PDF). J. Res. Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST. 106 (1): 25–46. doi:10.6028/jres.106.003. PMC 4865288. PMID 27500016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- F. J. Smith (1973). "Standard Kilogram Weights – A Story of Precision Fabrication" (PDF). Platinum Metals Review. 17 (2): 66–68.

- Unità razionali di elettromagnetismo, Giorgi (1901)

- "Historical figures ... Giovanni Giorgi". International Electrotechnical Commission. 2011. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- Superintendent of the Metrology Department of the National Physical Laboratory, UK

- Barrel, H. (1962), "The Metre", Contemp. Phys., 3 (6): 415–34, Bibcode:1962ConPh...3..415B, doi:10.1080/00107516208217499

- Phelps, F. M., III (1966), "Airy Points of a Meter Bar", Am. J. Phys., 34 (5): 419–22, Bibcode:1966AmJPh..34..419P, doi:10.1119/1.1973011

- Resolution 6 – Proposal for establishing a practical system of units of measurement. 9th Conférence Générale des Poids et Mesures (CGPM). 12–21 October 1948. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- Resolution 6 – Practical system of units. 10th Conférence Générale des Poids et Mesures (CGPM). 5–14 October 1954. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- Resolution 7 – Writing and printing of unit symbols and of numbers. 9th Conférence Générale des Poids et Mesures (CGPM). 12–21 October 1948. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- "Leap seconds". Time Service Department, U.S. Naval Observatory. Archived from the original on 12 March 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- F. Richard Stephenson (1982). "Historical Eclipses". Scientific American. 247 (4): 154–163. Bibcode:1982SciAm.247d.154S. Archived from the original on 15 January 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- Fenna, Donald (2002). Dictionary of Weights, Measures and Units. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860522-5.

- Pretley, B.W. (1992). Crovini, L; Quinn, T.J (eds.). The continuing evolution in the definitions and realisations of the SI units of measurement. La metrologia ai confini tra fisica e tecnologia (Metrology at the Frontiers of Physics and Technology). Bologna: Societa Italiana di Fisica. ISBN 978-0-444-89770-1.

- "A brief history of SI". NIST. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- "CIPM, 1948 and 9th CGPM, 1948". International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM). Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- Resolution 3 – Triple point of water; thermodynamic scale with a single fixed point; unit of quantity of heat (joule). 9th Conférence Générale des Poids et Mesures (CGPM). 12–21 October 1948. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- Resolution 3 – Definition of the thermodynamic temperature scale and. 10th Conférence Générale des Poids et Mesures (CGPM). 5–14 October 1954. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- Barry N. Taylor (1992). The Metric System: The International System of Units (SI). U. S. Department of Commerce. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-941375-74-0. (NIST Special Publication 330, 1991 ed.)

- radian, steradian, hertz, newton, joule, watt, coloumb, volt, farad, ohm, weber, tesla, henry, degree Celsius, lumen, lux

- "Techniques for Approximating the International Temperature Scale of 1990" (PDF). Sèvres: BIPM. 1997 [1990]. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- de Laeter, JR; Böhlke, JK; de Bièvre, P; Hidaka, H; HS, Peiser; Rosman, KJR; Taylor, PDP (2003). "Atomic Weights of the Elements: Review 2000 (IUPAC Technical Report)" (PDF). Pure Appl. Chem. International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. 75 (6): 690–691. doi:10.1351/pac200375060683. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 January 2013. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- Resolution 3 – SI unit of thermodynamic temperature (kelvin) and Resolution 4 – Definition of the SI unit of thermodynamic temperature (kelvin). 9th Conférence Générale des Poids et Mesures (CGPM). 12–21 October 1948. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- "Base unit definitions: Meter". NIST. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- G. Girard (1994). "The Third Periodic Verification of National Prototypes of the Kilogram (1988–1992)". Metrologia. 31 (4): 317–336. Bibcode:1994Metro..31..317G. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/31/4/007.

- "Practical realization of the definitions of some important units". SI brochure, Appendix 2. BIPM. 9 September 2010. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- Materese, Robin (14 May 2018). "Kilogram: Introduction". nist.gov.

- Treese, Steven A. (2018). History and measurement of the base and derived units. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. p. 92. ISBN 978-3-319-77577-7. OCLC 1036766223.

- "Resolution proposal submitted to the IUPAP Assembly by Commission C2 (SUNAMCO)" (PDF). International Union of Pure and Applied Physics. 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- Mills, Ian (29 September 2010). "On the possible future revision of the International System of Units, the SI" (PDF). CCU. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 January 2012. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- Mills, Ian (29 September 2010). "Draft Chapter 2 for SI Brochure, following redefinitions of the base units" (PDF). CCU. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 June 2013. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- "Resolution 12 of the 23rd meeting of the CGPM (2007)". Sèvres, France: General Conference on Weights and Measures. Archived from the original on 21 April 2013. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- "Towards the "new SI"". International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM). Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2011.

- "On the possible future revision of the International System of Units, the SI – Draft Resolution A" (PDF). International Committee for Weights and Measures (CIPM). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 August 2011. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- Kühne, Michael (22 March 2012). "Redefinition of the SI". Keynote address, ITS9 (Ninth International Temperature Symposium). Los Angeles: NIST. Archived from the original on 18 June 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- "9th edition of the SI Brochure". BIPM. 2019. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- "Resolution 1: On the possible future revision of the International System of Units, the SI" (PDF). 24th meeting of the General Conference on Weights and Measures. Sèvres, France: International Bureau for Weights and Measures. 21 October 2011. It was not expected to be adopted until some prerequisite conditions are met, and in any case not before 2014. See"Possible changes to the international system of units". IUPAC Wire. 34 (1). January–February 2012.

- "General Conference on Weights and Measures approves possible changes to the International System of Units, including redefinition of the kilogram" (PDF) (Press release). Sèvres, France: General Conference on Weights and Measures. 23 October 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 February 2012. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- Mohr, Peter (2 November 2011). "Redefining the SI base units". NIST Newsletter. NIST. Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- "Resolutions adopted by the CGPM at its 25th meeting (18–20 November 2014)" (PDF). Sèvres, France: International Bureau for Weights and Measures. 21 November 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 March 2015. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- "Draft Resolution A "On the revision of the International System of units (SI)" to be submitted to the CGPM at its 26th meeting (2018)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 April 2018. Retrieved 5 May 2018.