Berlin Wall Monument (Chicago)

The Berlin Wall Monument in Chicago is an exhibit on display at the Western Brown Line CTA station. The monument contains a large segment of the Berlin Wall and a plaque describing its dedication to the city. The Berlin Wall represented one of the great political, economic, and ideological divides of the twentieth century[1] between two major powers: the United States and the Soviet Union.

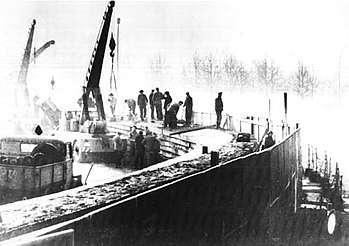

The Berlin Wall Monument in Chicago, exhibiting the side originally facing West Germany | |

| Coordinates | 41.966165°N 87.688513°W |

|---|---|

| Location | Lincoln Square, Chicago |

| Type | Wall fragment |

| Material | Concrete |

Background

See Also: World War II, The Cold War, Berlin Wall

World War II affected many countries, Germany in particular. After the years of total war, the Nazi regime in Germany finally surrendered to the Allied countries in spring of 1945.[2] Later, the Empire of Japan surrendered shortly after the second atomic bomb devastated their country.[3] In the post-war years, tensions between two of the victorious powers, the United States and the Soviet Union emerged. The former was growing ever more capitalistic and the latter pursued communism. Germany, not only geographically located in the center of Europe, was the center of the divided between the powers. Germany, especially its capital, Berlin, was partitioned by the victors of the Second World War; there were a few parts but the major division was east-west dividing the capitalist countries from the communist one.

A great wall was erected almost two decades later to strengthen the division, literally and figuratively. Built in 1961, the Berlin Wall represented one of the great political, economic, and ideological divides of the twentieth century[1] between two major powers: the United States and the Soviet Union. It was 96 miles in length. The conflict between these two powers affected the global community, namely Germany. Even after it was demolished, the wall symbolized divisions in Germany and the rest of the world, ones that arguably still exist today. Cornell sociologist Christine Leuenberger described the effects of the wall and its ultimate fall by arguing that "It became the landmark that symbolized the Cold War… the Berlin Wall also left a lasting impression on the psyche of the German people".[1] She further argues that The Berlin Wall "provides a salient and powerful example of how material culture intersects with knowledge production in the psychological sciences".[1]

After the fall

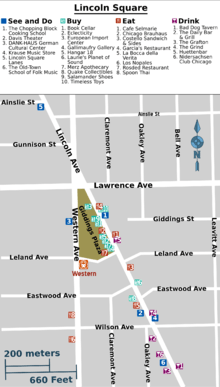

Since the fall of the Berlin Wall on 9 November 1989, fragments of the Berlin Wall have been donated to various cities in the world. Chicago was offered a piece of the wall in 2008 by the German government[4][5] and was placed in the Lincoln Square neighborhood due to its German roots.[5] It is on permanent display at the Western Brown Line Station. Lincoln Square is just southwest of Ravenswood in the northern part of Chicago.

The particular segment of the wall donated came from the fourth phase of the Berlin Wall's construction,[6] called Grenzmauer 75.

The dedication was attended by 120 residents and included several prominent individuals such as Erich Himmel of United German American Societies of Greater Chicago, Alderman Gene Schulter, Chicago Transit Authority President Ron Huberman, then-mayor of Chicago Richard M. Daley and the U.S. diplomat and chargé d'affaires to Germany, James D. Bindenagel.[7] It is one of two fragments of the wall on display in Illinois; the other is in the Ronald Reagan Peace Garden at Eureka College in Eureka, Illinois.

Description

The wall segment is visible on both sides. The side that originally faced West Germany contains sprayed graffiti and messages from the time the wall was standing;[8] the side that faced East Germany, on the other hand, is entirely blank.[5] It is simple to tell which side faced West Berlin and which side faced East Berlin. The former has graffiti and the latter is bare. "'So you're talking about the free side, the side that the Americans were able to release at the end of (World War II). That's why we have all this graffiti on it, because they were free, they were allowed to do things, and express themselves,' Nicholle Dombrowski, executive director of the DANK Haus German American Cultural Center, said. 'The east side is traditionally clean, because they were under a communist government at that time, and they were not allowed to express themselves, whatsoever.'".[8] The piece serves as a metaphoric and literal reminder of the two very different sides of a long, bitter conflict.

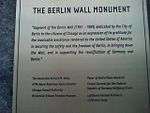

The monument also contains a plaque describing the dedication and reasoning behind why the wall fragment was donated. The inscription reads:

- "Segment of the Berlin Wall (1961 - 1989) dedicated by the City of Berlin to the citizens of Chicago as an expression of its gratitude for the invaluable assistance rendered by the United States of America in securing the safety and freedom of Berlin, in bringing down the Wall, and in supporting reunification of Germany and Berlin."

The inscription contains affirmations of acceptance from many representative individuals and businesses of both Chicago and Germany at the time including Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley, Mayor of Berlin Klaus Wowereit, German Consul General Wolfgang Droutz, Lufthansa, and the Chicago Transit Authority.

References

- Leuenberger, Christine. "Constructions of the Berlin Wall: How Material Culture Is Used in Psychological Theory." Social Problems. 53.1 (2006): 18-37. Print.

- Evans, Richard J. Third Reich at War. London: Allen Lane, 2008. Print.

- "Potsdam Declaration." AtomicArchive.com. National Science Digital Library (NSDL) (1998-2015), n.d. Web. 22 Feb. 2016.

- "German Neighborhood in Chicago - Lincoln Square and Ravenswood". Chicago Dossier. Denali Multimedia LLC. Archived from the original on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- B., Mona. "A Piece of Berlin in Lincoln Square". Lincoln Square Ravenswood Chamber of Commerce. Lincoln Square Ravenswood Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- Veronse, Keith (23 August 2012). "Your piece of the Berlin Wall is not special". io9. Gawker Media. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- "Berlin Wall Installation". The Office of Community, Government and International Affairs. DePaul University. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- Tucker, Dorothy (14 May 2012). "Chicago To Show Off German Roots During NATO Summit". CBS Chicago. CBS Radio Inc. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

Further reading

- Glassie, Henry. "Chapter 2: Material Culture." Material Culture. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1999. 41-86. Print.

- Keating, Ann D. Chicago Neighborhoods and Suburbs: A Historical Guide. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008. Print.

- Leuenberger, Christine. "Constructions of the Berlin Wall: How Material Culture Is Used in Psychological Theory." Social Problems. 53.1 (2006): 18-37. Print.

- Ulbricht, J.. "Reflections on Visual and Material Culture: An Example from Southwest Chicago". Studies in Art Education 49.1 (2007): 59–72. Web

- Wiener, Jon. How We Forgot the Cold War: A Historical Journey across America (2012)