Hinchinbrook Island

Hinchinbrook Island (or Pouandai to the original Biyaygiri inhabitants[2]) lies east of Cardwell and north of Lucinda, separated from the northern coast of Queensland, Australia by the narrow Hinchinbrook Channel. Hinchinbrook Island is part of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park and wholly protected within the Hinchinbrook Island National Park, except for a small and abandoned resort. It is the largest island on the Great Barrier Reef.[3] It is also the largest island national park in Australia.[4][5]

| Native name: Pouandai | |

|---|---|

Hinchinbrook Island looking west (i-cubed Landsat 7). | |

Hinchinbrook | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Coral Sea |

| Coordinates | 18°13′46″S 146°13′58″E |

| Total islands | great barrier reef |

| Area | 393 km2 (152 sq mi)[1] |

| Length | 52 km (32.3 mi) |

| Width | 10 km (6 mi) |

| Highest elevation | 1,121 m (3,678 ft) |

| Highest point | Mount Bowen |

| Administration | |

Australia | |

| State | Queensland |

| LGA | Cassowary Coast Region |

Natural heritage

Hinchinbrook Island is made up of late Palaeozoic igneous rocks.[6] The main 16-kilometre-long (9.9-mile) pluton in the east of the island, the Hinchinbrook Granite, is composed of various hypersolvus granites and intrudes volcanics, granodiorites, and granites.[6][7] The island and coastal ranges are thought to have been thrust up as blocks with subsidence between them to form the coastal plain with the summit level of the island being an older dissected surface that has been uplifted to approximately 1 kilometre (0.62 miles) or more above sea level. The Hinchinbrook Channel that separates the island from the mainland is considered to be fault controlled.

Since the last Ice Age 18,000 years ago sea level has risen. Once there was a significant rugged coastal range, now there is Hinchinbrook Island. To the west is the mangrove-fringed Hinchinbrook Channel with 164 km2 (63 sq mi) of robust mangrove estuaries.[8] The channel is the valley of the Herbert River flooded following the last glacial period.[9] The island is only separated from the mainland at times of high sea-level such as the present and is thought to have had dry land connections to the mainland for most of the past few million years. Further west is the Cardwell Range Escarpment rainforest. East of Hinchinbrook Island lies the Coral Sea, Great Barrier Reef Lagoon and Great Barrier Reef.

To the north of Hinchinbrook Island, Rockingham Bay hosts densely vegetated continental islands e.g. Garden Island, Goold Island, Brook Islands Group, Family Island Group, Bedarra Island and Dunk Island east of Mission Beach. South of Hinchinbrook Island, the Cardwell Range gives way to the Herbert River floodplain and delta.

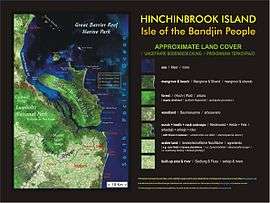

Missionary Bay is at the northern end of Hinchinbrook Island National Park. Natural features of this biodiverse area include 50 km2 (19 sq mi) of dense mangrove communities lining the shoreline.[8] Many botanists believe the mangrove forests along the island's western coast are the most diverse in the country.[5] 31 different species of mangrove has been identified.[10] A shallow subhorizontal tidal zone has extensive offshore sea grass beds grazed by dugong. The beach stone-curlew thrives on the island, unlike on mainland beaches because vehicles are banned.[5]

The eastern coastline of Hinchinbrook Island is punctuated with headland outcrops, incised drainage conduits, forest, secluded sandy pocket beaches and sand dunes. Mangroves are in proximity to freshwater streams. At Ramsay Bay on the northeast coast, a transgressive dune barrier or tombolo links Cape Sandwich, a granite outlier at the northeastern tip of the island, to the main part of the island. The barrier is widest in the north with a maximum width of about one kilometre (0.62 miles) and narrows to the south to a width of about 100 to 200 metres (330 to 660 feet).[11] The barrier, which consists mainly of aeolian sands, extends more than 30 metres (98 feet) below the present sea level in places. It is thought to have been formed in two major episodes, the older dunes being partly drowned during an early Holocene marine transgression (9500-6000 C-14 years BP) with the later generation of dunes forming within the last 900 C-14 years BP.[12]

Hinchinbrook Island is described as a "wilderness area," wild and rugged with soaring mountainous peaks. Hinchinbrook Island's highest mountain is Mount Bowen, 1,121 metres (3,678 feet) above sea level. Other notable mountain summits are The Thumb (981 m, 3,219 ft), Mount Diamantina (953 m, 3,127 ft) and Mount Straloch (922 m, 3,025 ft).[13] Terrestrial vegetation types include thick shrubs, heath, bushland and forest. The island habitat provides refuge for numerous endangered species, both flora and fauna such as the giant tree frog.

The local climate is tropical, warm to mildly cool and dry during the winter months. The summer monsoon wet is warm to hot and humid, coinciding with the tropical cyclone season. The island has no reefs in the waters surrounding it, most likely due to fresh water runoff from the island.[10]

History

Hinchinbrook Island or Pouandai was originally inhabited by the indigenous Biyaygiri people.[5]

Warrgamay (also known as Waragamai, Wargamay, Wargamaygan, Biyay, and Warakamai) is an Australian Aboriginal language in North Queensland. The language region includes the Herbert River area, Ingham, Hawkins Creek, Long Pocket, Herbert Vale, Niagara Vale, Yamanic Creek, Herbert Gorge, Cardwell, Hinchinbrook Island and the adjacent mainland.[14]

Shell middens and fish traps are evidence of their activities.[15] Fish were an important source of food for Aboriginal people living in the area. The Bandjin fish trap rock formations exploited the cyclic tidal regime, not only capturing fish, but also holding their catch alive for days. At times, many fish would be caught in the traps. These fish would not be killed nor eaten, instead they were left for the birds. To this day fish are still captured by these traps feeding the local birds.

In 1770, British Captain James Cook on HMS Endeavour sailed past at some distance to the east, naming Mount Hinchinbrook without realising that it was an island. Lieutenant Phillip Parker King on his surveying voyage in 1819 suspected it was separated from the mainland but could not confirm this. It was not until 1843, when Captain Blackwood on HMS Fly stayed two weeks in the area, that the British were able to verify that it was a distinct landmass, naming it Hinchinbrook Island.[16] The name is from Hinchingbrooke House, in Huntingdon, England, as John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich was First Lord of the Admiralty,[17] and the naming of Hinchinbrook Island, Brampton Island and Montague Island in the South Sandwich Islands are evidence of Cook's thanks to the 4th Earl.

Early interactions between British navigators and the Biyaygiri were mostly amicable. Lieutenant Jeffreys of HMS Kangaroo landed there in 1815 as did Lieutenant P.P. King in 1819 and both reported friendly dealings with the indigenous population.[18] In his 1843 voyage, Captain Blackwood of HMS Fly also had peaceful communications with the Biyaygiri initially, but conflict occurred on several occasions when the sailors were pelted with rocks, resulting in a number of islanders being shot.[19]

Following the establishment of the township of Cardwell in 1864 on the mainland across from Hinchinbrook, relations between the British and the Biyaygiri soon deteriorated. Inspector John Murray of the Native Police led a group of settlers and troopers on a month long expedition through the island in 1867, abducting and interrogating the native people in order to obtain information about some possible shipwreck survivors.[20] In 1872, after the killing of two white fishermen at nearby Goold Island, a large punitive mission led by sub-Inspector Robert Arthur Johnstone scoured Hinchinbrook Island administering summary justice and returning with several captured young Indigenous children.[21] A visitor to Cardwell at the time reported that one of these children was raped by the police and that the settlers openly talked of "the slaughter of whole camps not only of men, but of women and children".[22] Through violent incidents such as these, the population of Hichinbrook Island was rapidly reduced to a handful of survivors. Reverend Edward Fuller attempted to set up a mission on the island in 1874 but was forced to abandon it after being informed of the massacres and consequently not seeing "a solitary black" in nine months living there.[23]

In the following decades Europeans settled on Hinchinbrook Island. Their main activities were fishing, farming and mining. In 1932, Hinchinbrook Island was declared a national park.[5][15] In 1942, during World War II, an American B-24 Liberator bomber of the United States Army Air Force crashed into Mount Straloch, a mountain on the island, killing all 12 crewmen on board.[24] After World War II, commercial crocodile hunting in the area reduced numbers nearly to the point of extinction by the 1960s.[5]

The 2008 feature movie Nim's Island was partly filmed on the island.[25]

Tourism

The island had a single provider of accommodation called the Hinchinbrook Island Wilderness Lodge;[4] however, it closed in 2010 as a result of financial difficulties caused by the financial crisis of 2007–2008. Several months later it was struck by Cyclone Yasi. The infrastructure has since been looted and left to decay.[26] It is located on the northeastern corner of the island at Cape Richards.[3]

Destinations and regulations

Hinchinbrook Island, Hinchinbrook Channel and the coastal plain south to the Herbert River Delta(Lucinda) is a unique biogeographical region.

Along the east coast of the island is the 32 km (20 mi) long Thorsborne Trail. The trail was named in honour of environmental activists Arthur and Margaret Thorsborne.[15]

Marine nature based activities include sightseeing cruises, sailing, outrigger canoeing, swimming, snorkelling and scuba diving. Sea kayaking is possible east of Hinchinbrook Island; west, the island is known saltwater crocodile habitat.

Hinchinbrook Island camping is by permit only.[15] Visitor numbers to the island is restricted. The aim is to preserve the island's biodiversity and limit environmental degradation. Open fires are not permitted.[15]

Access

The Bruce Highway connects Townsville, Lucinda, Cardwell, and Cairns. Locally the Bruce Highway within Cardwell town limits is known as Victoria Street. Regular scheduled coach services operate from the transit zone in Brasenose Street, Cardwell and Townsville Road in Ingham. Hinchinbrook resorts and Helloworld in Ingham run bus shuttles to Townsville and return to Lucinda for people hiking the Thorsborne trail. Queensland Rail has regular services operating, transiting from the Cardwell Rail Station in Roma Street.

Shipwreck

In 2011, the shipwreck of a thirty-metre (98-foot) longboat was discovered on the shores of Ramsay Bay by a fisherman.[27] It is thought that the wreck is about 130 years old and was uncovered by Cyclone Yasi.

See also

- Agnes Island

- List of islands of Australia

- Oyster Point

- Protected areas of Queensland

- The Thumb (Queensland)

References

- Ellison, J., 2000. Wetlands, Biodiversity and the Ramsar Convention, Chapt. 5; Ed. Hails, A.J. Case Study 1: Australia, Mangroves on Hinchinbrook Island. Australian Institute of Marine Science. Townsville, QLD. Australia.

- Poignant, Roslyn (2004). Professional Savages, Captive Lives and Western Spectacle. New Haven: Yale. p. 22.

- "Hinchinbrook Island". The Sydney Morning Herald. 8 February 2004. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

- "Hinchinbrook Island". queenslandholidays.com.au. Tourism Queensland. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

- Hema maps. (1997). Discover Australia's National Parks. pp 178 – 179 Random House. ISBN 1-875992-47-2

- Stephenson, P. J. (July–December 1990). "Layering in felsic granites in the main East pluton, Hinchinbrook Island, North Queensland, Australia". Geological Journal. 25 (3–4): 325–336. doi:10.1002/gj.3350250315.

- "INGHAM, SHEET SE55-10, SECOND EDITION 2000". Geological Survey of Queensland.

- Ellison, J., 2000. Wetlands, Biodiversity and the Ramsar Convention, Chapt. 5; Ed. Hails, A.J. Case Study 1: Australia, Mangroves on Hinchinbook Island. Australian Institute of Marine Science. Townsville, QLD. Australia.

- "Thorsborne Trail, Hinchinbrook Island National Park". The State of Queensland (Department of Environment and Resource Management). 2011. Retrieved 2 July 2011.

- David Hopley; Scott Smithers (2010). "Queensland". In Eric C.F. Bird (ed.). Encyclopedia of World's Coastal Landforms. Springer. p. 1260. ISBN 978-1-4020-8638-0.

- Pye, Kenneth; Jim Mazzullo (July 1994). "Effects of tropical weathering on quartz grain shape; an example from northeastern Australia". Journal of Sedimentary Research. 64 (3a): 500–507. doi:10.1306/D4267DE8-2B26-11D7-8648000102C1865D.

- Pye, Kenneth; E.G Rhodes (April 1985). "Holocene development of an episodic transgressive dune barrier, Ramsay Bay, North Queensland, Australia". Marine Geology. 64 (3–4): 189–202. doi:10.1016/0025-3227(85)90104-5.

- "Queensland Globe". State of Queensland. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

-

- "About Hinchinbrook Island". Department of Environment and Resource Management. 11 October 2010. Archived from the original on 15 September 2012. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

- Beete Jukes, Joseph (1846). Narrative of the Surveying Voyage of HMS Fly. T. & W. Boone. p. 91. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

beete jukes narrative fly vol 1.

- "Fourth Earl of Sandwich". www.hinchhouse.org.uk. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- King, Philip Parker King (1827). Narrative of a survey of the intertropical and western coasts of Australia. Murray. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

philip parker king rockingham bay.

- Beete Jukes, Joseph (1846). Narrative of the surveying voyage of HMS Fly. T. & W. Boone. pp. 92–94. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

beete jukes narrative fly vol 1.

- "SEARCH FOR WHITE MEN ON HINCHINBROOK ISLAND". The Queenslander. II (98). Queensland, Australia. 14 December 1867. p. 8. Retrieved 4 March 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- "CARDWELL, NORTHERN QUEENSLAND". Empire (6209). New South Wales, Australia. 28 February 1872. p. 3. Retrieved 4 March 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- "BLACK AND WHITE IN QUEENSLAND". The Sydney Morning Herald. LXIX (11, 142). New South Wales, Australia. 2 February 1874. p. 3. Retrieved 4 March 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- "THE ABORIGINAL MISSION ON HINCHINBROOK ISLAND". The Toowoomba Chronicle And Queensland Advertiser (929). Queensland, Australia. 10 October 1874. p. 3. Retrieved 4 March 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- Peter Michael & Rory Gibson (2 May 2009). "Air force urged to investigate mystery women on doomed bomber". The Courier Mail. Queensland Newspapers. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

- Rebekah van Druten (20 March 2008). "Feisty Foster indulges in lighter role". ABC News Online. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

- Bavas, Josh (2 May 2014). "North Qld tourism developments still in tatters after GFC and Cyclone Yasi". ABC News. Australia: ABC.net.au. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- Tony Moore (19 April 2011). "Mystery shipwreck unearthed in north Queensland". Brisbane Times. Fairfax Media. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

Further reading

- Matthew Fletcher et al.: Walking in Australia. Lonely Planet 2001. ISBN 0-86442-669-0

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hinchinbrook Island. |

- www.hinchinbrook.info – A community site documenting development pressures on Hinchinbrook Island and Channel

- Hinchinbrook Island National Park – Department of National Parks, Recreation, Sport and Racing