Polysaccharide

Polysaccharides (/ˌpɒliˈsækəraɪd/) are the most abundant carbohydrate found in food. They are long chain polymeric carbohydrates composed of monosaccharide units bound together by glycosidic linkages. This carbohydrate can react with water (hydrolysis) using amylase enzymes at catalyst, which produces constituent sugars (monosaccharides, or oligosaccharides). They range in structure from linear to highly branched. Examples include storage polysaccharides such as starch and glycogen, and structural polysaccharides such as cellulose and chitin.

Polysaccharides are often quite heterogeneous, containing slight modifications of the repeating unit. Depending on the structure, these macromolecules can have distinct properties from their monosaccharide building blocks. They may be amorphous or even insoluble in water.[1] When all the monosaccharides in a polysaccharide are the same type, the polysaccharide is called a homopolysaccharide or homoglycan, but when more than one type of monosaccharide is present they are called heteropolysaccharides or heteroglycans.[2][3]

Natural saccharides are generally composed of simple carbohydrates called monosaccharides with general formula (CH2O)n where n is three or more. Examples of monosaccharides are glucose, fructose, and glyceraldehyde.[4] Polysaccharides, meanwhile, have a general formula of Cx(H2O)y where x is usually a large number between 200 and 2500. When the repeating units in the polymer backbone are six-carbon monosaccharides, as is often the case, the general formula simplifies to (C6H10O5)n, where typically 40 ≤ n ≤ 3000.

As a rule of thumb, polysaccharides contain more than ten monosaccharide units, whereas oligosaccharides contain three to ten monosaccharide units; but the precise cutoff varies somewhat according to convention. Polysaccharides are an important class of biological polymers. Their function in living organisms is usually either structure- or storage-related. Starch (a polymer of glucose) is used as a storage polysaccharide in plants, being found in the form of both amylose and the branched amylopectin. In animals, the structurally similar glucose polymer is the more densely branched glycogen, sometimes called "animal starch". Glycogen's properties allow it to be metabolized more quickly, which suits the active lives of moving animals.

Cellulose and chitin are examples of structural polysaccharides. Cellulose is used in the cell walls of plants and other organisms, and is said to be the most abundant organic molecule on Earth.[5] It has many uses such as a significant role in the paper and textile industries, and is used as a feedstock for the production of rayon (via the viscose process), cellulose acetate, celluloid, and nitrocellulose. Chitin has a similar structure, but has nitrogen-containing side branches, increasing its strength. It is found in arthropod exoskeletons and in the cell walls of some fungi. It also has multiple uses, including surgical threads. Polysaccharides also include callose or laminarin, chrysolaminarin, xylan, arabinoxylan, mannan, fucoidan and galactomannan.

Function

Structure

Nutrition polysaccharides are common sources of energy. Many organisms can easily break down starches into glucose; however, most organisms cannot metabolize cellulose or other polysaccharides like chitin and arabinoxylans. These carbohydrate types can be metabolized by some bacteria and protists. Ruminants and termites, for example, use microorganisms to process cellulose.

Even though these complex polysaccharides are not very digestible, they provide important dietary elements for humans. Called dietary fiber, these carbohydrates enhance digestion among other benefits. The main action of dietary fiber is to change the nature of the contents of the gastrointestinal tract, and to change how other nutrients and chemicals are absorbed.[6][7] Soluble fiber binds to bile acids in the small intestine, making them less likely to enter the body; this in turn lowers cholesterol levels in the blood.[8] Soluble fiber also attenuates the absorption of sugar, reduces sugar response after eating, normalizes blood lipid levels and, once fermented in the colon, produces short-chain fatty acids as byproducts with wide-ranging physiological activities (discussion below). Although insoluble fiber is associated with reduced diabetes risk, the mechanism by which this occurs is unknown.[9]

Not yet formally proposed as an essential macronutrient (as of 2005), dietary fiber is nevertheless regarded as important for the diet, with regulatory authorities in many developed countries recommending increases in fiber intake.[6][7][10][11]

Storage polysaccharides

Starch

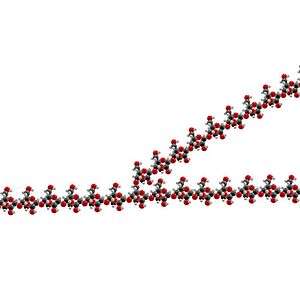

Starch is a glucose polymer in which glucopyranose units are bonded by alpha-linkages. It is made up of a mixture of amylose (15–20%) and amylopectin (80–85%). Amylose consists of a linear chain of several hundred glucose molecules, and Amylopectin is a branched molecule made of several thousand glucose units (every chain of 24–30 glucose units is one unit of Amylopectin). Starches are insoluble in water. They can be digested by breaking the alpha-linkages (glycosidic bonds). Both humans and other animals have amylases, so they can digest starches. Potato, rice, wheat, and maize are major sources of starch in the human diet. The formations of starches are the ways that plants store glucose.

Glycogen

Glycogen serves as the secondary long-term energy storage in animal and fungal cells, with the primary energy stores being held in adipose tissue. Glycogen is made primarily by the liver and the muscles, but can also be made by glycogenesis within the brain and stomach.[12]

Glycogen is analogous to starch, a glucose polymer in plants, and is sometimes referred to as animal starch,[13] having a similar structure to amylopectin but more extensively branched and compact than starch. Glycogen is a polymer of α(1→4) glycosidic bonds linked, with α(1→6)-linked branches. Glycogen is found in the form of granules in the cytosol/cytoplasm in many cell types, and plays an important role in the glucose cycle. Glycogen forms an energy reserve that can be quickly mobilized to meet a sudden need for glucose, but one that is less compact and more immediately available as an energy reserve than triglycerides (lipids).

In the liver hepatocytes, glycogen can compose up to 8 percent (100–120 grams in an adult) of the fresh weight soon after a meal.[14] Only the glycogen stored in the liver can be made accessible to other organs. In the muscles, glycogen is found in a low concentration of one to two percent of the muscle mass. The amount of glycogen stored in the body—especially within the muscles, liver, and red blood cells[15][16][17]—varies with physical activity, basal metabolic rate, and eating habits such as intermittent fasting. Small amounts of glycogen are found in the kidneys, and even smaller amounts in certain glial cells in the brain and white blood cells. The uterus also stores glycogen during pregnancy, to nourish the embryo.[14]

Glycogen is composed of a branched chain of glucose residues. It is stored in liver and muscles.

- It is an energy reserve for animals.

- It is the chief form of carbohydrate stored in animal body.

- It is insoluble in water. It turns brown-red when mixed with iodine.

- It also yields glucose on hydrolysis.

Schematic 2-D cross-sectional view of glycogen. A core protein of glycogenin is surrounded by branches of glucose units. The entire globular granule may contain approximately 30,000 glucose units.[18]

Schematic 2-D cross-sectional view of glycogen. A core protein of glycogenin is surrounded by branches of glucose units. The entire globular granule may contain approximately 30,000 glucose units.[18]

Inulin

Inulin is a naturally occurring polysaccharide, Complex carbohydrate composed of Dietary fiber a plant-derived food that cannot be completely broken down by human digestive enzymes.

Structural polysaccharides

Arabinoxylans

Arabinoxylans are found in both the primary and secondary cell walls of plants and are the copolymers of two sugars: arabinose and xylose. They may also have beneficial effects on human health.[19]

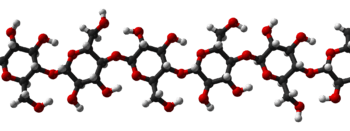

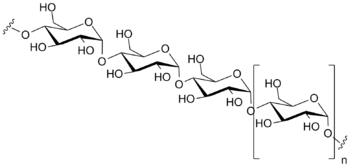

Cellulose

The structural components of plants are formed primarily from cellulose. Wood is largely cellulose and lignin, while paper and cotton are nearly pure cellulose. Cellulose is a polymer made with repeated glucose units bonded together by beta-linkages. Humans and many animals lack an enzyme to break the beta-linkages, so they do not digest cellulose. Certain animals such as termites can digest cellulose, because bacteria possessing the enzyme are present in their gut. Cellulose is insoluble in water. It does not change color when mixed with iodine. On hydrolysis, it yields glucose. It is the most abundant carbohydrate in nature.

Chitin

Chitin is one of many naturally occurring polymers. It forms a structural component of many animals, such as exoskeletons. Over time it is bio-degradable in the natural environment. Its breakdown may be catalyzed by enzymes called chitinases, secreted by microorganisms such as bacteria and fungi, and produced by some plants. Some of these microorganisms have receptors to simple sugars from the decomposition of chitin. If chitin is detected, they then produce enzymes to digest it by cleaving the glycosidic bonds in order to convert it to simple sugars and ammonia.

Chemically, chitin is closely related to chitosan (a more water-soluble derivative of chitin). It is also closely related to cellulose in that it is a long unbranched chain of glucose derivatives. Both materials contribute structure and strength, protecting the organism.

Pectins

Pectins are a family of complex polysaccharides that contain 1,4-linked α-D-galactosyl uronic acid residues. They are present in most primary cell walls and in the non-woody parts of terrestrial plants.

Acidic polysaccharides

Acidic polysaccharides are polysaccharides that contain carboxyl groups, phosphate groups and/or sulfuric ester groups.

Bacterial capsular polysaccharides

Pathogenic bacteria commonly produce a thick, mucous-like, layer of polysaccharide. This "capsule" cloaks antigenic proteins on the bacterial surface that would otherwise provoke an immune response and thereby lead to the destruction of the bacteria. Capsular polysaccharides are water-soluble, commonly acidic, and have molecular weights on the order of 100,000 to 2,000,000 daltons. They are linear and consist of regularly repeating subunits of one to six monosaccharides. There is enormous structural diversity; nearly two hundred different polysaccharides are produced by E. coli alone. Mixtures of capsular polysaccharides, either conjugated or native are used as vaccines.

Bacteria and many other microbes, including fungi and algae, often secrete polysaccharides to help them adhere to surfaces and to prevent them from drying out. Humans have developed some of these polysaccharides into useful products, including xanthan gum, dextran, welan gum, gellan gum, diutan gum and pullulan.

Most of these polysaccharides exhibit useful visco-elastic properties when dissolved in water at very low levels.[20] This makes various liquids used in everyday life, such as some foods, lotions, cleaners, and paints, viscous when stationary, but much more free-flowing when even slight shear is applied by stirring or shaking, pouring, wiping, or brushing. This property is named pseudoplasticity or shear thinning; the study of such matters is called rheology.

Viscosity of Welan gum Shear rate (rpm) Viscosity (cP) 0.3 23330 0.5 16000 1 11000 2 5500 4 3250 5 2900 10 1700 20 900 50 520 100 310

Aqueous solutions of the polysaccharide alone have a curious behavior when stirred: after stirring ceases, the solution initially continues to swirl due to momentum, then slows to a standstill due to viscosity and reverses direction briefly before stopping. This recoil is due to the elastic effect of the polysaccharide chains, previously stretched in solution, returning to their relaxed state.

Cell-surface polysaccharides play diverse roles in bacterial ecology and physiology. They serve as a barrier between the cell wall and the environment, mediate host-pathogen interactions, and form structural components of biofilms. These polysaccharides are synthesized from nucleotide-activated precursors (called nucleotide sugars) and, in most cases, all the enzymes necessary for biosynthesis, assembly and transport of the completed polymer are encoded by genes organized in dedicated clusters within the genome of the organism. Lipopolysaccharide is one of the most important cell-surface polysaccharides, as it plays a key structural role in outer membrane integrity, as well as being an important mediator of host-pathogen interactions.

The enzymes that make the A-band (homopolymeric) and B-band (heteropolymeric) O-antigens have been identified and the metabolic pathways defined.[21] The exopolysaccharide alginate is a linear copolymer of β-1,4-linked D-mannuronic acid and L-guluronic acid residues, and is responsible for the mucoid phenotype of late-stage cystic fibrosis disease. The pel and psl loci are two recently discovered gene clusters that also encode exopolysaccharides found to be important for biofilm formation. Rhamnolipid is a biosurfactant whose production is tightly regulated at the transcriptional level, but the precise role that it plays in disease is not well understood at present. Protein glycosylation, particularly of pilin and flagellin, became a focus of research by several groups from about 2007, and has been shown to be important for adhesion and invasion during bacterial infection.[22]

Chemical identification tests for polysaccharides

Periodic acid-Schiff stain (PAS)

Polysaccharides with unprotected vicinal diols or amino sugars (where some hydroxyl groups are replaced with amines) give a positive periodic acid-Schiff stain (PAS). The list of polysaccharides that stain with PAS is long. Although mucins of epithelial origins stain with PAS, mucins of connective tissue origin have so many acidic substitutions that they do not have enough glycol or amino-alcohol groups left to react with PAS.

See also

- Glycan

- Oligosaccharide nomenclature

- Polysaccharide encapsulated bacteria

References

- Varki A, Cummings R, Esko J, Freeze H, Stanley P, Bertozzi C, Hart G, Etzler M (1999). Essentials of glycobiology. Cold Spring Har J. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. ISBN 978-0-87969-560-6.

- IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "homopolysaccharide (homoglycan)". doi:10.1351/goldbook.H02856

- IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "heteropolysaccharide (heteroglycan)". doi:10.1351/goldbook.H02812

- Matthews, C. E.; K. E. Van Holde; K. G. Ahern (1999) Biochemistry. 3rd edition. Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 0-8053-3066-6

- N.A.Campbell (1996) Biology (4th edition). Benjamin Cummings NY. p.23 ISBN 0-8053-1957-3

- "Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients) (2005), Chapter 7: Dietary, Functional and Total fiber" (PDF). US Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Library and National Academy of Sciences, Institute of Medicine, Food and Nutrition Board. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-27.

- Eastwood M, Kritchevsky D (2005). "Dietary fiber: how did we get where we are?". Annu Rev Nutr. 25: 1–8. doi:10.1146/annurev.nutr.25.121304.131658. PMID 16011456.

- Anderson JW, Baird P, Davis RH, et al. (2009). "Health benefits of dietary fiber" (PDF). Nutr Rev. 67 (4): 188–205. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00189.x. PMID 19335713. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-10. Retrieved 2017-10-25.

- Weickert MO, Pfeiffer AF (2008). "Metabolic effects of dietary fiberand any other substance that consume and prevention of diabetes". J Nutr. 138 (3): 439–42. doi:10.1093/jn/138.3.439. PMID 18287346.

- "Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for carbohydrates and dietary fibre". EFSA Journal. 8 (3): 1462. March 25, 2010. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2010.1462.

- Jones PJ, Varady KA (2008). "Are functional foods redefining nutritional requirements?". Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 33 (1): 118–23. doi:10.1139/H07-134. PMID 18347661. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-13.

- Anatomy and Physiology. Saladin, Kenneth S. McGraw-Hill, 2007.

- "Animal starch". Merriam Webster. Retrieved May 11, 2014.

- Campbell, Neil A.; Brad Williamson; Robin J. Heyden (2006). Biology: Exploring Life. Boston, Massachusetts: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-250882-7.

- Moses SW, Bashan N, Gutman A (December 1972). "Glycogen metabolism in the normal red blood cell". Blood. 40 (6): 836–43. PMID 5083874.

- INGERMANN, ROLFF L.; VIRGIN, GARTH L. (January 20, 1987). "Glycogen Content and Release of Glucose from Red blood cells of the Sipunculan Worm Themiste Dyscrita" (PDF). jeb.biologists.org/. Journal of Experimental Biology. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- Miwa I, Suzuki S (November 2002). "An improved quantitative assay of glycogen in erythrocytes". Annals of Clinical Biochemistry. 39 (Pt 6): 612–3. doi:10.1258/000456302760413432. PMID 12564847.

- Page 12 in: Exercise physiology: energy, nutrition, and human performance, By William D. McArdle, Frank I. Katch, Victor L. Katch, Edition: 6, illustrated, Published by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006, ISBN 0-7817-4990-5, ISBN 978-0-7817-4990-9, 1068 pages

- Mendis, M; Simsek, S (15 December 2014). "Arabinoxylans and human health". Food Hydrocolloids. 42: 239–243. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2013.07.022.

- Viscosity of Welan Gum vs. Concentration in Water. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2009-10-02.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Guo H, Yi W, Song JK, Wang PG (2008). "Current understanding on biosynthesis of microbial polysaccharides". Curr Top Med Chem. 8 (2): 141–51. doi:10.2174/156802608783378873. PMID 18289083.

- Cornelis P (editor) (2008). Pseudomonas: Genomics and Molecular Biology (1st ed.). Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-19-6.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Polysaccharides. |