The Princess Casamassima

The Princess Casamassima is a novel by Henry James, first published as a serial in The Atlantic Monthly in 1885 and 1886 and then as a book in 1886. It is the story of an intelligent but confused young London bookbinder, Hyacinth Robinson, who becomes involved in radical politics and a terrorist assassination plot. The book is unusual in the Jamesian canon for dealing with such a violent political subject. But it is often paired with another novel published by James in the same year, The Bostonians, which is also concerned with political issues, though in a much less tragic manner.

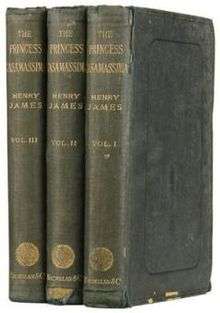

First edition | |

| Author | Henry James |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Macmillan and Co., London |

Publication date | 22 October 1886 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| Pages | Volume one, 252; volume two, 257; volume three, 242 |

Plot summary

Amanda Pynsent, an impoverished seamstress, has adopted Hyacinth Robinson, the illegitimate son of her old friend Florentine Vivier, a French woman of less than sterling repute, and an English lord. Florentine had stabbed her lover to death several years ago, and Pinnie (as Miss Pynsent is nicknamed) takes Hyacinth to see her as she lies dying at Millbank prison. Hyacinth eventually learns that the dying woman is his mother and that she murdered his father.

Many years pass. Hyacinth, now a young man and a skilled bookbinder, meets revolutionary Paul Muniment and gets involved in radical politics. Hyacinth also has a coarse but lively girlfriend, Millicent Henning, and one night they go to the theatre. There Hyacinth meets the radiantly beautiful Princess Casamassima (Christina Light, from James' earlier novel, Roderick Hudson).

The Princess has become a revolutionary herself and now lives apart from her dull husband. Meanwhile, Hyacinth has committed himself to carrying out a terrorist assassination, though the exact time and place have not yet been specified to him. Hyacinth visits the Princess at her country home and tells her about his parents. When he returns to London, Hyacinth finds Pinnie dying. He comforts her in her final days, then travels to France and Italy on his small inheritance.

This trip completes Hyacinth's conversion to a love for the sinful but beautiful world, and away from violent revolution. Still, he does not attempt to escape his vow to carry out the assassination. But when the order comes, he turns the gun on himself instead of its intended victim.

Major themes

At first glance, this novel seems very different from James' usual work because of its concentration on radical politics and less-than-wealthy characters. And it's true that the book comes closer to classic Naturalism than any other long fiction in the Jamesian canon. The influence of French Naturalists like Émile Zola is evident in the prison scenes, the depiction of the revolutionary movement, and the deterministic nature of Hyacinth's heredity.

But the novel also explores themes familiar from James' other work. Hyacinth always seems to be an outsider, unable to participate fully in the life around him. He commits himself to the revolution, then hesitates and wavers. He is attracted to the beauty of the world, but can't enjoy it completely because he sees how it is purchased at the cost of so much human suffering. When the final call comes, he can see no way out of his dilemma: either the state will kill him if he carries out the assassination, or the revolutionaries will kill him if he doesn't.

Such hesitations and divided loyalties are common among James' perceptive central characters. Hyacinth's case is particularly acute because his actual life is at stake. In his preface to the New York Edition of the novel, James audaciously compared Hyacinth to Hamlet and Lear. While some may cavil at such comparisons, others believe that Hyacinth's fate does rise almost to classic tragedy.

The novel shows a broad panorama of European life at all levels, and the many supporting characters are presented with a generous helping of humor in a story which shows the influence of Dickens from James' early reading.

Critical evaluation

The Princess Casamassima has had a checkered critical history. Early critics, such as Rebecca West, admired the novel's workmanship and characters, but not the melodramatic plot, while later critics, such as Lionel Trilling, found it a convincing account of political reality. Despite the many well-realised supporting characters, the novel stands on its portrayal of anti-hero Hyacinth Robinson. In his New York Edition preface, James said that he believed he had successfully presented a flawed, but affecting, hero; some critics have disagreed, one dismissing Hyacinth as "a bit of a wimp".

The Guardian's review, published in 1887, noted that The Princess Casamassima kept to the promise of Roderick Hudson, which James's other novels had not met. The review praised James's characterisation of Hyacinth's friends and comrades, but nonetheless found that James "does not understand" the English, with the result that his characters are "rather extremely clever attempts and conjectures than real life studies." The review concluded: "there is a great deal of interest in the book, interest which is not lessened by the fact that its catastrophe is quite unexpected, or rather is one which most readers are likely not to expect, exactly because it is so obvious."[1]

In popular culture

Princess Casamassima appears prominently, as a vampire and revolutionary, in Kim Newman's Anno Dracula series, notably Anno Dracula 1895, where she is one of the Council of Seven Days, an anarchist organization taken from G.K. Chesterton's The Man Who Was Thursday, and in Anno Dracula 1899: One Thousand Monsters, where she is one of several vampires seeking sanctuary in Japan. The book also features in Thomas Pynchon's Against the Day, being read by a literate dog.

References

- "A mistake to misunderstand". The Guardian. 28 June 2003 [23 February 1887].

- The Novels of Henry James by Edward Wagenknecht (New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co., 1983) ISBN 0-8044-2959-6

- A Henry James Encyclopedia by Robert Gale (New York: Greenwood Press, 1989) ISBN 0-313-25846-5

- Meaning in Henry James by Millicent Bell (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press 1991) ISBN 0-674-55763-8

- A Companion to Henry James Studies edited by Daniel Fogel (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press 1993) ISBN 0-313-25792-2

- Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays edited by Ruth Yeazell (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall 1994) ISBN 0-13-380973-0

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Princess Casamassima. |

- Original magazine publication of The Princess Casamassima (1885-86)

- First book version of The Princess Casamassima (1886)

- Author's preface to the New York Edition version of The Princess Casamassima (1908)

- Note on the various texts of The Princess Casamassima at the Library of America web site

- The Princess Casamassima Map