Parry–Romberg syndrome

Parry–Romberg syndrome (PRS) is a rare disease characterized by progressive shrinkage and degeneration of the tissues beneath the skin, usually on only one side of the face (hemifacial atrophy) but occasionally extending to other parts of the body.[1] An autoimmune mechanism is suspected, and the syndrome may be a variant of localized scleroderma, but the precise cause and pathogenesis of this acquired disorder remains unknown. It has been reported in the literature as a possible consequence of sympathectomy. The syndrome has a higher prevalence in females and typically appears between 5 – 15 years of age.

| Parry–Romberg syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Progressive hemifacial atrophy |

| |

| a 17-year-old girl with Parry–Romberg syndrome. The subcutaneous tissue and underlying facial muscles on the right side of the face are severely atrophic, while the left side is unaffected. | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

In addition to the connective tissue disease, the condition is sometimes accompanied by neurological, ocular and oral symptoms. The range and severity of associated symptoms and findings are highly variable.

Signs and symptoms

Skin and connective tissues

Initial facial changes usually involve the area of the face covered by the temporal or buccinator muscles. The disease progressively spreads from the initial location, resulting in atrophy of the skin and its adnexa, as well as underlying subcutaneous structures such as connective tissue, (fat, fascia, cartilage, bones) and/or muscles of one side of the face.[2] The mouth and nose are typically deviated towards the affected side of the face.[3]

The process may eventually extend to involve tissues between the nose and the upper corner of the lip, the upper jaw, the angle of the mouth, the area around the eye and brow, the ear, and/or the neck.[2][3] The syndrome often begins with a circumscribed patch of scleroderma in the frontal region of the scalp which is associated with a loss of hair and the appearance of a depressed linear scar extending down through the midface on the affected side. This scar is referred to as a "coup de sabre" lesion because it resembles the scar of a wound made by a sabre, and is indistinguishable from the scar observed in frontal linear scleroderma.[4][5]

In 20% of cases, the hair and skin overlying affected areas may become hyperpigmented or hypopigmented with patches of unpigmented skin. In up to 20% of cases the disease may involve the ipsilateral (on the same side) or contralateral (on the opposite side) neck, trunk, arm, or leg.[6] The cartilage of the nose, ear and larynx can be involved. The disease has been reported to affect both sides of the face in 5-10% of the cases.[4]

Symptoms and physical findings usually become apparent during the first or early during the second decade of life. The average age of onset is nine years of age,[2] and the majority of individuals experience symptoms before 20 years of age. The disease may progress for several years before eventually going into remission (abruptly ceasing).[2]

Neurological

Neurological abnormalities are common. Roughly 45% of people with Parry–Romberg syndrome are also afflicted with trigeminal neuralgia (severe pain in the tissues supplied by the ipsilateral trigeminal nerve, including the forehead, eye, cheek, nose, mouth and jaw) and/or migraine (severe headaches that may be accompanied by visual abnormalities, nausea and vomiting).[6][7]

10% of affected individuals develop a seizure disorder as part of the disease.[6] The seizures are typically Jacksonian in nature (characterized by rapid spasms of a muscle group that subsequently spread to adjacent muscles) and occur on the side contralateral to the affected side of the face.[2] Half of these cases are associated with abnormalities in both the gray and white matter of the brain—usually ipsilateral but sometimes contralateral—that are detectable on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan.[6][8]

Ocular

Enophthalmos (recession of the eyeball within the orbit) is the most common eye abnormality observed in Parry–Romberg syndrome. It is caused by a loss of subcutaneous tissue around the orbit. Other common findings include drooping of the eyelid (ptosis), constriction of the pupil (miosis), redness of the conjunctiva, and decreased sweating (anhidrosis) of the affected side of the face. Collectively, these signs are referred to as Horner's syndrome. Other ocular abnormalities include ophthalmoplegia (paralysis of one or more of the extraocular muscles) and other types of strabismus, uveitis, and heterochromia of the iris.[9][10]

Oral

The tissues of the mouth, including the tongue, gingiva, teeth and soft palate are commonly involved in Parry–Romberg syndrome.[3] 50% of affected individuals develop dental abnormalities such as delayed eruption, dental root exposure, or resorption of the dental roots on the affected side. 35% have difficulty or inability to normally open the mouth or other jaw symptoms, including temporomandibular joint disorder and spasm of the muscles of mastication on the affected side. 25% experience atrophy of one side of the upper lip and tongue.[6]

Causes

The fact that some people affected with this disease have circulating antinuclear antibodies in their serum supports the theory that Parry–Romberg syndrome may be an autoimmune disease, specifically a variant of localized scleroderma.[11] Several instances have been reported where more than one member of a family has been affected, prompting speculation of an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. However, there has also been at least one report of monozygotic twins in which only one of the twins was affected, casting doubt on this theory. Further, the National Organization for Rare Disorders has stated there is currently no evidence that Parry–Romberg syndrome is genetic or that it can be passed on to children.[12] Various other theories about the cause and pathogenesis have been suggested, including alterations in the peripheral sympathetic nervous system (perhaps as a result of trauma or infection involving the cervical plexus or the sympathetic trunk), as the literature reported it following sympathectomy, disorders in migration of cranial neural crest cells, or chronic cell-mediated inflammatory process of the blood vessels. It is likely that the disease results from different mechanisms in different people, with all of these factors potentially being involved.[2]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis can be made solely on the basis of history and physical examination in people who present with only facial asymmetry. For those who report neurological symptoms such as migraine or seizures, MRI scan of the brain is the imaging modality of choice. A diagnostic lumbar puncture and serum test for autoantibodies may also be indicated in people who present with a seizure disorder of recent onset.[6] Oligoclonal bands and an elevated IgG index may be found in 50% of the patients.[13]

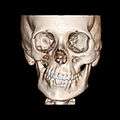

A 3D, soft tissue reconstruction of a CT scan of a 17-year-old girl with Parry Romberg syndrome.

A 3D, soft tissue reconstruction of a CT scan of a 17-year-old girl with Parry Romberg syndrome. CT scan3D bone reconstruction of a 17-year-old girl with Parry Romberg syndrome.

CT scan3D bone reconstruction of a 17-year-old girl with Parry Romberg syndrome.

Management

Medical

Medical management may involve immunosuppressive drugs such as methotrexate, corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, and azathioprine. No randomized controlled trials have yet been conducted to evaluate such treatments, so the benefits have not been clearly established.[6]

Surgical

Affected individuals may benefit from autologous fat transfer or fat grafts to restore a more normal contour to the face. However, greater volume defects may require microsurgical reconstructive surgery which may involve the transfer of an island parascapular fasciocutaneous flap or a free flap from the groin, rectus abdominis muscle (Transverse Rectus Abdominis Myocutaneous or "TRAM" flap) or latissimus dorsi muscle to the face. Severe deformities may require additional procedures, such as pedicled temporal fascia flaps, cartilage grafts, bone grafts, orthognathic surgery, and bone distraction.[14] The timing of surgical intervention is controversial; some surgeons prefer to wait until the disease has run its course[3] while others recommend early intervention.[15]

Epidemiology

Parry–Romberg syndrome appears to occur randomly and for unknown reasons. Prevalence is higher in females than males, with a ratio of roughly 3:2. The condition is observed on the left side of the face about as often as on the right side.[16]

History

The disease was first described in 1825 by Caleb Hillier Parry (1755–1822), in a collection of his medical writings which were published posthumously by his son Charles Henry Parry (1779–1860).[17] It was described a second time in 1846 by Moritz Heinrich Romberg (1795–1873) and Eduard Heinrich Henoch (1820–1910).[18] German neurologist Albert Eulenburg (1840–1917) was the first to use the descriptive title "progressive hemifacial atrophy" in 1871.[19][20][21]

See also

- Hemifacial microsomia

- List of cutaneous conditions

- Trigeminal trophic lesion

References

- Sharma M, Bharatha A, Antonyshyn OM, Aviv RI, Symons SP (February 2012). "Case 178: Parry-Romberg syndrome". Radiology. 262 (2): 721–5. doi:10.1148/radiol.11092104. PMID 22282187.

- Gorlin RJ, Cohen MM, Hennekam R (2001). "Chapter 24: Syndromes with unusual facies: well-known syndromes". Syndromes of the head and neck (4th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 977–1038. ISBN 978-0-19-511861-2.

- Saraf, S (2006). "Chapter 3: Developmental disorders of oral and paraoral structures". Textbook of oral pathology. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers Ltd. pp. 31–76. ISBN 978-81-8061-655-6.

- Saraf, S (2006). "Features of syndromes and conditions affecting oral and extra oral structures". Textbook of oral pathology. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers Ltd. pp. 547–54. ISBN 978-81-8061-655-6.

- Wartenberg, R (1945). "Progressive facial hemiatrophy (abstract)". Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry. 54 (2): 75–97. doi:10.1001/archneurpsyc.1945.02300080003001.

- Stone, J (2006). "Neurological rarity: Parry-Romberg syndrome" (PDF). Practical Neurology. 6 (3): 185–8. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2006.089037.

- parry_romberg at NINDS

- Leäo M, da Silva ML (December 1994). "Progressive hemifacial atrophy with agenesis of the head of the caudate nucleus". Journal of Medical Genetics. 31 (12): 969–71. doi:10.1136/jmg.31.12.969. PMC 1016702. PMID 7891383.

- Muchnick RS, Aston SJ, Rees TD (November 1979). "Ocular manifestations and treatment of hemifacial atrophy". American Journal of Ophthalmology. 88 (5): 889–97. doi:10.1016/0002-9394(79)90567-1. PMID 507167.

- Saxena AK, Bhatia IS, Ahuja SP (August 1979). "Influence of various levels of acetate and glucose on the in vitro biosynthesis of lipids from 2-14C-acetate and U-14C-glucose by buffalo mammary gland slices". Zeitschrift für Tierphysiologie, Tierernahrung und Futtermittelkunde. 42 (2): 57–64. doi:10.1136/jnnp.37.9.997. PMC 494830.

- Lewkonia RM, Lowry RB (February 1983). "Progressive hemifacial atrophy (Parry-Romberg syndrome) report with review of genetics and nosology". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 14 (2): 385–90. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320140220. PMID 6601461.

- "Parry Romberg Syndrome". NORD’s Rare Disease Database. National Organization for Rare Disorders. 2016. Retrieved 2018-05-19.

- Vix J, Mathis S, Lacoste M, Guillevin R, Neau JP (July 2015). "Neurological Manifestations in Parry-Romberg Syndrome: 2 Case Reports". Medicine. 94 (28): e1147. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000001147. PMC 4617071. PMID 26181554.

- Iñigo F, Jimenez-Murat Y, Arroyo O, Fernandez M, Ysunza A (2000). "Restoration of facial contour in Romberg's disease and hemifacial microsomia: experience with 118 cases". Microsurgery. 20 (4): 167–72. doi:10.1002/1098-2752(2000)20:4<167::AID-MICR4>3.0.CO;2-D. PMID 10980515.

- University of Wisconsin Hospitals and Clinics Authority (2011-05-17). "UW health surgeon reconstructs young girl's face". News for referring physicians. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Hospitals and Clinics Authority. Archived from the original on 2011-09-29. Retrieved 2011-08-02.

- Rogers BO (October 13–18, 1963). "Progressive facial hemiatrophy (Romberg's diseases): a review of 772 cases". In Broadbent TR, Anderson B (ed.). Transactions of the third international congress of plastic surgery (International Congress Series No. 66). Third International Congress of Plastic Surgery. Amsterdam: Excerpta Medica. pp. 681–9.

- Parry, CH (1825). Parry, CH (ed.). Collections from the unpublished medical writings of the late Caleb Hillier Parry, M.D., F.R.S. 1. London: Underwoods. pp. 478–80.

- Romberg MH, Henoch EH (1846). "Krankheiten des nervensystems (IV: Trophoneurosen)". Klinische ergebnisse (in German). Berlin: Albert Förstner. pp. 75–81.

- Eulenburg, A (1871). "Hemiatrophia facialis progressiva". Lehrbuch der functionellen nervenkrankheiten auf physiologischer basis (in German). Berlin: Verlag von August Hirschwald. pp. 712–26.

- synd/1285 at Who Named It?

- Cory RC, Clayman DA, Faillace WJ, McKee SW, Gama CH (April 1997). "Clinical and radiologic findings in progressive facial hemiatrophy (Parry-Romberg syndrome)". AJNR. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 18 (4): 751–7. PMID 9127045.

Further reading

- Karim A, Laghmari M, Ibrahimy W, Essakali HN, Mohcine Z (October 2005). "[Neuroretinitis, Parry-Romberg syndrome, and scleroderma]". Journal Francais d'Ophtalmologie (in French). 28 (8): 866–70. doi:10.1016/S0181-5512(05)81008-3. PMID 16249769.

- Lakhani PK, David TJ (February 1984). "Progressive hemifacial atrophy with scleroderma and ipsilateral limb wasting (Parry-Romberg syndrome)". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 77 (2): 138–9. doi:10.1177/014107688407700215. PMC 1439690. PMID 6737396.

- Larner AJ, Bennison DP (September 1993). "Some observations on the aetiology of progressive hemifacial atrophy ("Parry-Romberg syndrome")". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 56 (9): 1035–6. doi:10.1136/jnnp.56.9.1035-a. PMC 489747. PMID 8410030.

- Miller MT, Spencer MA (1995). "Progressive hemifacial atrophy. A natural history study". Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society. 93: 203–15, discussion 215–7. PMC 1312058. PMID 8719679.

- Pinheiro TP, Silva CC, Silveira CS, Botelho PC, Pinheiro MD, Pinheiro JJ (March 2006). "Progressive Hemifacial Atrophy--case report". Medicina Oral, Patologia Oral y Cirugia Bucal. 11 (2): E112-4. PMID 16505785.

- Zafarulla MY (July 1985). "Progressive hemifacial atrophy: a case report". The British Journal of Ophthalmology. 69 (7): 545–7. doi:10.1136/bjo.69.7.545. PMC 1040666. PMID 4016051.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |