Pericoronitis

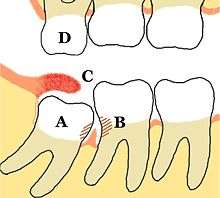

Pericoronitis is inflammation of the soft tissues surrounding the crown of a partially erupted tooth,[1] including the gingiva (gums) and the dental follicle.[2] The soft tissue covering a partially erupted tooth is known as an operculum, an area which can be difficult to access with normal oral hygiene methods. The hyponym operculitis technically refers to inflammation of the operculum alone.

| Pericoronitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Operculitis |

| |

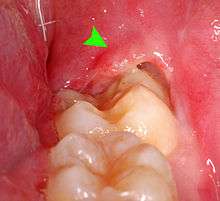

| Pericoronitis associated with the lower right third molar (wisdom tooth). | |

| Specialty | Dentistry |

Pericoronitis is caused by an accumulation of bacteria and debris beneath the operculum, or by mechanical trauma (e.g. biting the operculum with the opposing tooth).[3] Pericoronitis is often associated with partially erupted and impacted mandibular third molars (lower wisdom teeth),[4] often occurring at the age of wisdom tooth eruption (15-26).[5][6] Other common causes of similar pain from the third molar region are food impaction causing periodontal pain, pulpitis from dental caries (tooth decay), and acute myofascial pain in temporomandibular joint disorder.

Pericoronitis is classified into chronic and acute. Chronic pericoronitis can present with no or only mild symptoms and long remissions between any escalations to acute pericoronitis.[7] Acute pericoronitis is associated with a wide range of symptoms including severe pain, swelling and fever.[3] Sometimes there is an associated pericoronal abscess (an accumulation of pus). This infection can spread to the cheeks, orbits/periorbits, and other parts of the face or neck, and occasionally can lead to airway compromise (e.g. Ludwig's angina) requiring emergency hospital treatment. The treatment of pericoronitis is through pain management and by resolving the inflammation. The inflammation can be resolved by flushing the debris or infection from the pericoronal tissues or by removing the associated tooth or operculum. Retaining the tooth requires improved oral hygiene in the area to prevent further acute pericoronitis episodes. Tooth removal is often indicated in cases of recurrent pericoronitis. The term is from the Greek peri, "around", Latin corona "crown" and -itis, "inflammation".

Classification

The definition of pericoronitis is inflammation in the soft tissues surrounding the crown of a tooth. This encompasses a wide spectrum of severity, making no distinction to the extent of the inflammation into adjacent tissues or whether there is associated active infection (pericoronal infection caused by micro-organisms sometimes leading to a pus filled pericoronal abscess or cellulitis).

Typically cases involve acute pericoronitis of lower third molar teeth. During "teething" in young children, pericoronitis can occur immediately preceding eruption of the deciduous teeth (baby or milk teeth).

The International Classification of Diseases entry for pericoronitis lists acute and chronic forms.

Acute

Acute pericoronitis (i.e. sudden onset and short lived, but significant, symptoms) is defined as "varying degrees of inflammatory involvement of the pericoronal flap and adjacent structures, as well as by systemic complications."[4] Systemic complications refers to signs and symptoms occurring outside of the mouth, such as fever, malaise or swollen lymph nodes in the neck.

Chronic

Pericoronitis may also be chronic or recurrent, with repeated episodes of acute pericoronitis occurring periodically. Chronic pericoronitis may cause few if any symptoms,[8] but some signs are usually visible when the mouth is examined.

Signs and symptoms

The signs and symptoms of pericoronitis depend upon the severity, and are variable:

- Pain, which gets worse as the condition develops and becomes severe.[2][9] The pain may be throbbing and radiate to the ear, throat, temporomandibular joint, posterior submandibular region and floor of the mouth.[2][4] There may also be pain when biting.[9] Sometimes the pain disturbs sleep.

- Tenderness, erythema (redness) and edema (swelling) of the tissues around the involved tooth,[9] which is usually partially erupted into the mouth. The operculum is characteristically very painful when pressure is applied.[2]

- Halitosis resulting from the bacteria putrefaction of proteins in this environment releasing malodorous volatile sulfur compounds.[4]

- Bad taste in the mouth from exudation of pus.[9][10]

- Intra-oral halitosis.[9]

- Formation of pus,[9] which can be seen exuding from beneath the operculum (i.e. a pericoronal abscess), especially when pressure is applied to the operculum.[2]

- Signs of trauma on the operculum, such as indentations of the cusps of the upper teeth,[9] or ulceration.[4] Rarely, the soft tissue around the crown of the involved tooth may show a similar appearance to necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis.[11]

- Trismus (difficulty opening the mouth).[9] resulting from inflammation/infection of the muscles of mastication.[11][12]

- Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing).[9]

- Cervical lymphadenitis (inflammation and swelling of the lymph nodes in the neck),[9] especially of the submandibular nodes.[2]

- Facial swelling, and rubor, often of the cheek that overlies the angle of the jaw.[2][4]

- Pyrexia (fever).[9]

- Leukocytosis (increased white blood cell count).[8]

- Malaise (general feeling of being unwell).[8]

- Loss of appetite.

- The radiographic appearance of the local bone can become more radiopaque in chronic pericoronitis.[8]

Causes

Pericoronitis occurs because the operculum (the soft tissue directly overlying the partially erupted tooth) creates a "plaque stagnation area",[11] which can accumulate food debris and micro-organisms (particularly plaque).[4] This leads to an inflammatory response in the adjacent soft tissues.[10]

Sometimes Pericoronal infection can spread into adjacent potential spaces (including the sublingual space, submandibular space, parapharyngeal space, pterygomandibular space, infratemporal space, submasseteric space and buccal space[12]) to areas of the neck or face[2] resulting in facial swelling, or even airway compromise (called Ludwig's angina).[12]

Bacteria

Inadequate cleaning of the operculum space allows stagnation of bacteria and any accumulated debris. This can be a result of poor access due to limited room in the case of the 3rd molars. Pericoronal infection is normally caused by a mixture of bacterial species present in the mouth, such as Streptococci and particularly various anaerobic species.[11][13] This can result in abscess formation. Left untreated, the abscess can spontaneously drain into the mouth from beneath the operculum. In chronic pericoronitis, drainage may happen through an approximal sinus tract. The chronically inflamed soft tissues around the tooth may give few if any symptoms. This can suddenly become symptomatic if new debris becomes trapped[8] or if the host immune system becomes compromised and fails to keep the chronic infection in check (e.g. during influenza or upper respiratory tract infections, or a period of stress).[13]

Tooth position

- When an opposing tooth bites into the operculum, it can initiate or exacerbate pericoronitis resulting in a spiraling cycle [13] of inflammation and trauma.[4]

- Over-eruption of the opposing tooth into the unoccupied space left by the stalled eruption of a tooth is a risk factor to operculum trauma from biting.

- Teeth that fail to erupt completely (commonly the lower mandibular third molars) are often the result of limited space for eruption, or a non-ideal angle of tooth eruption causing tooth impaction.

- The presence of supernumerary teeth (extra teeth) makes pericoronitis more likely.[8]

Diagnosis

| Pericoronitis | Temporomandibular joint disorder |

|---|---|

| Swelling and tenderness of operculum and around wisdom tooth | Dull, aching pain around face, around ear, angle of jaw (masseter), and inside mouth behind upper wisdom tooth (lateral pterygoid) |

| Bad taste | Headaches |

| Disturbed sleep | Does not disturb sleep |

| Poorly responsive to analgesics | Responds to analgesics |

| Possibly limited mouth opening (trismus) | Possibly trismus, joint noises (e.g. clicking upon opening) and deviation of mandible |

The presence of dental plaque or infection beneath an inflamed operculum without other obvious causes of pain will often lead to a pericoronitis diagnosis; therefore, elimination of other pain and inflammation causes is essential. For pericoronal infection to occur, the affected tooth must be exposed to the oral cavity, which can be difficult to detect if the exposure is hidden beneath thick tissue or behind an adjacent tooth. Severe swelling and restricted mouth opening may limit examination of the area.[11] Radiographs can be used to rule out other causes of pain and to properly assess the prognosis for further eruption of the affected tooth.[12]

Sometimes a "migratory abscess" of the buccal sulcus occurs with pericoronal infection, where pus from the lower third molar region tracks forwards in the submucosal plane, between the body of the mandible and the attachment of the buccinator muscle to the mandible. In this scenario, pus may spontaneously discharge via an intra-oral sinus located over the mandibular second or first molar, or even the second premolar.

Similar causes of pain, some which can occur in conjunction with pericoronitis may include:

- Dental caries (tooth decay) of the wisdom tooth and of the distal surface of the second molar is common. Tooth decay may cause pulpitis (toothache) to occur in the same region, and this may cause pulp necrosis and the formation of a periapical abscess associated with either tooth.

- Food can also become stuck between the wisdom tooth and the tooth in front, termed food packing, and cause acute inflammation in a periodontal pocket when the bacteria become trapped. A periodontal abscess may even form by this mechanism.

- Pain associated with temporomandibular joint disorder and myofascial pain also often occurs in the same region as pericoronitis. J are easily missed diagnoses in the presence of mild and chronic pericoronitis, and the latter may not be contributing greatly to the individual's pain (see table).

It is rare for pericoronitis to occur in association with both lower third molars at the same time, despite the fact that many young people will have both lower wisdom teeth partially erupted. Therefore, bilateral pain from the lower third molar region is unlikely to be caused by pericoronitis and more likely to be muscular in origin.

Prevention

Prevention of pericoronitis can be achieved by removing impacted third molars before they erupt into the mouth,[13] or through preemptive operculectomy.[13] A treatment controversy exists about the necessity and timing of the removal of asymptomatic, disease-free impacted wisdom teeth which prevents pericoronitis. Proponents of early extraction cite the cumulative risk for extraction over time, the high probability that wisdom teeth will eventually decay or develop gum disease and costs of monitoring to retained wisdom teeth.[14] Advocates for retaining wisdom teeth cite the risk and costs of unnecessary operations and the ability to monitor the disease through clinical exam and radiographs.[15]

Management

Since pericoronitis is a result of inflammation of the pericoronal tissues of a partially erupted tooth, management can include applying pain management gels for the mouth consisting of Lignocaine, a numbing agent. Definitive treatment can only be through preventing the source of inflammation. This is either through improved oral hygiene or by removal of the plaque stagnation areas through tooth extraction or gingival resection.[4] Often acute symptoms of pericoronitis are treated before the underlying cause is addressed.

Acute pericoronitis

When possible, immediate definitive treatment of acute pericoronitis is recommended because surgical treatment has been shown to resolve the spread of the infection and pain, with a quicker return of function.[16] Also immediate treatment avoids overuse of antibiotics (preventing antibiotic resistance).

However, surgery is sometimes delayed in an area of acute infection, with the help of pain relief and antibiotics, for the following reasons:

- Reduces the risk of causing an infected surgical site with delayed healing (e.g. osteomyelitis or cellulitis).

- Avoids reduced efficiency of local anesthetics caused by the acidic environment of infected tissues.

- Resolves the limited mouth opening, making oral surgery easier.

- Patients may better cope with the dental treatment when free from pain.

- Allows for adequate planning with correctly allocated procedure time.

Firstly, the area underneath the operculum is gently irrigated to remove debris and inflammatory exudate.[4] Often warm saline[11] is used but other solutions may contain hydrogen peroxide, chlorhexidine or other antiseptics. Irrigation may be assisted in conjunction with Debridement (removal of plaque, calculus and food debris) with periodontal instruments. Irrigation may be enough to relieve any associated pericoronal abscess; otherwise a small incision can be made to allow drainage. Smoothing an opposing tooth which bites into the affected operculum can eliminate this source of trauma.[11]

Home care may involve regular use of warm salt water mouthwashes/mouth baths.[4] A randomized clinical trial found green tea mouth rinse effective in controlling pain and trismus in acute cases of pericoronitis.[17]

Following treatment, if there are systemic signs and symptoms, such as facial or neck swelling, cervical lymphadenitis, fever or malaise, a course of oral antibiotics is often prescribed,.[4] Common antibiotics used are from the β-lactam antibiotic group,[18] clindamycin[13] and metronidazole.[11]

If there is dysphagia or dyspnoea (difficulty swallowing or breathing), then this usually means there is a severe infection and an emergency admission to hospital is appropriate so that intravenous medications and fluids can be administered and the threat to the airway monitored. Sometimes semi-emergency surgery may be arranged to drain a swelling that is threatening the airway.

Definitive treatment

If the tooth will not continue to erupt completely, definitive treatment involves either sustained oral hygiene improvements or removal of the offending tooth or operculum. The latter surgical treatment options are usually chosen in the case of impacted teeth with no further eruption potential, or in the case of recurrent episodes of acute pericoronitis despite oral hygiene instruction.

Oral hygiene

In some cases, removal of the tooth may not be necessary with meticulous oral hygiene to prevent buildup of plaque in the area.[11] Long term maintenance is needed to keep the operculum clean in order to prevent further acute episodes of inflammation. A variety of specialized oral hygiene methods are available to deal with hard to reach areas of the mouth, including small headed tooth brushes, interdental brushes, electronic irrigators and dental floss.

Operculectomy

This is a minor surgical procedure where the affected soft tissue covering and surrounding the tooth is removed. This leaves an area that is easy to keep clean, preventing plaque buildup and subsequent inflammation.[4] Sometimes operculectomy is not an effective treatment.[13] Typically operculectomy is done with a surgical scalpel, electrocautery, with lasers[19] or, historically, with caustic agents (trichloracetic acid)[11]

Tooth extraction

Removal of the associated tooth will eliminate the plaque stagnation area, and thus eliminate any further episodes of pericoronitis. Removal is indicated when the involved tooth will not erupt any further due to impaction or ankylosis; if extensive work would be required to restore structural damage; or to allow improved oral hygiene. Sometimes the opposing tooth is also extracted if no longer required.[11]

Extraction of teeth which are involved in pericoronitis carries a higher risk of dry socket, a painful complication which results in delayed healing.[8]

Prognosis

Once the plaque stagnation area is removed either through further complete tooth eruption or tooth removal then pericoronitis will likely never return. A non-impacted tooth may continue to erupt, reaching a position which eliminates the operculum. A transient and mild pericoronal inflammation often continues while this tooth eruption completes. With adequate space for sustained improved oral hygiene methods, pericoronitis may never return. However, when relying on just oral hygiene for impacted and partially erupted teeth, chronic pericoronitis with occasional acute exacerbation can be expected.

Dental infections such as a pericoronal abscess can develop into sepsis and be life-threatening in persons who have neutropenia. Even in people with normal immune function, pericoronitis may cause a spreading infection into the potential spaces of the head and neck. Rarely, the spread of infection from pericoronitis may compress the airway and require hospital treatment (e.g. Ludwig's angina), although the majority of cases of pericoronitis are localized to the tooth. Other potential complications of a spreading pericoronal abscess include peritonsillar abscess formation or cellulitis.[4]

Chronic pericoronitis may be the etiology for the development of paradental cyst, an inflammatory odontogenic cyst.

Epidemiology

Pericoronitis usually occurs in young adults,[11] around the time when wisdom teeth are erupting into the mouth. If the individual has reached their twenties without any attack of pericoronitis, it becomes substantially less likely one will occur thereafter.

References

- Douglass AB, Douglass JM (Feb 1, 2003). "Common dental emergencies". American Family Physician. 67 (3): 511–6. PMID 12588073.

- Fragiskos, Fragiskos D. (2007). Oral surgery. Berlin: Springer. p. 122. ISBN 978-3-540-25184-2.

- Laskaris, George (2003). Color Atlas of Oral Diseases. Thieme. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-58890-138-5. Retrieved 2008-05-31.

- Newman MG, Takei HH, Klokkevold PR, Carranza FA (2012). Carranza's clinical periodontology (11th ed.). St. Louis, Mo.: Elsevier/Saunders. pp. 103, 133, 331–333, 440, 447. ISBN 978-1-4377-0416-7.

- CA Bartzokas; GW Smith, eds. (1998). Managing Infections: Decision-making Options in Clinical Practice. Informa Health Care. p. 157. ISBN 978-1-85996-171-1. Retrieved 2008-05-31.

- Nguyen DH, Martin JT (Mar 15, 2008). "Common dental infections in the primary care setting". American Family Physician. 77 (6): 797–802. PMID 18386594.

- Moloney J, Stassen LFA (June–July 2009). "Pericoronitis: treatment and a clinical dilemma" (PDF). Journal of the Irish Dental Association. 55 (4): 190–192.

- Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CA, Bouquot JE (2002). Oral & maxillofacial pathology (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. pp. 73, 129, 133, 153, 154, 590, 608. ISBN 978-0721690032.

- Wray D, Stenhouse D, Lee D, Clark AJ (2003). Textbook of general and oral surgery. Edinburgh [etc.]: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 220–222. ISBN 978-0443070839.

- Soames JV, Southam JC (1999). Oral pathology (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-0192628947.

- Cawson RA, Odell EW (2002). Cawson's essentials of oral pathology and oral medicine (7th ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 82, 166. ISBN 9780443071058.

- Odell EW (2010). Clinical problem solving in dentistry (3rd ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 151–153. ISBN 9780443067846.

- Hupp JR, Ellis E, Tucker MR (2008). Contemporary oral and maxillofacial surgery (5th ed.). St. Louis, Mo.: Mosby Elsevier. ISBN 9780323049030.

- Dodson TB (Sep 2012). "The management of the asymptomatic, disease-free wisdom tooth: removal versus retention. (review)". Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 20 (2): 169–76. doi:10.1016/j.cxom.2012.06.005. PMID 23021394.

- "TA1: Guidance on the Extraction of Wisdom Teeth" (PDF). National Institute of Clinical Excellence. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- Johri, A; Piecuch, JF (November 2011). "Should teeth be extracted immediately in the presence of acute infection?". Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America. 23 (4): 507–11, v. doi:10.1016/j.coms.2011.07.003. PMID 21982602.

- https://www.ijoms.com/article/S0901-5027(14)00210-0/abstract

- Samaranayake, Lakshman P. (2009). Essential microbiology for dentistry. Elseveier. p. 71. ISBN 978-0702041679.

- Kravitz, ND; Kusnoto, B (April 2008). "Soft-tissue lasers in orthodontics: an overview". American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. 133 (4 Suppl): S110–4. doi:10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.01.026. PMID 18407017.