Manor

A manor is the basic unit of manorialism, which became the dominant economic system during parts of the European Middle Ages. It defined the relationship between the lord of the manor, and serfs and free peasants who worked various plots of land. In English law, Welsh law and Irish law, the lord held an estate in land (land title) which included the right to hold a manorial court. The court had jurisdiction over most of those who lived within the lands of the manor.

The smallest unit of land under the feudal system (which defined the military and legal relationships between nobles) is the fee (or fief), on which the manor became established through the process of time. In modern terms, the manor could be thought of as the "business" which the lord establishes on the fief, which is the area of land they have been granted. The manor is nevertheless often described as the basic feudal unit of land tenure and is historically connected with the territorial divisions of the march, county, hundred, parish and township.

Legal theory

The legal theory of the origin of manors refers them to a grant from the crown of a fee from the monarch's allodial lands, as stated in the following extract from Perkins's Treatise on the laws of England:

"The beginning of a manor was when the king gave a thousand acres of land, or greater or lesser parcel of land, unto one of his subjects and his heirs, which tenure is knight service at the least. And the donee did perhaps build a mansion house upon parcel of the same land, and of 20 acres, parcel of that which remained, or of a greater or lesser parcel, before the statute of Quia emptores did enfeoff a stranger to hold of him and his heirs to plough 10 acres of land, parcel of that which remained in his possession, and did enfeoff another of another parcel thereof to go to war with him against the Scots etc., and so by continuance of time made a manor".

It is still as the jurist Sir Joshua Williams terms it, a "fundamental rule" that all lands were originally derived from the crown and that the monarch is lord paramount mediate or immediate of all the land in the realm. A manor then arises when the holder of a parcel so granted or supposed to have been granted by the crown, and who is termed in relation thereto the lord of the manor, has in turn granted portions thereof to others who stand to him in the relation of tenants. Of the portion reserved by the lord for his own use, termed the demesne, part was occupied by villeins, with the duty of cultivating the rest for the lord's use. These were originally tenants at will and in a state of semi-serfdom but they became in course of time the copyhold tenants of the later law. It is of the essence of copyhold that it should be regulated by the custom of the manor, as evidenced in the manorial roll produced by the manorial court. Manors cannot be created at the present day because manorial courts cannot be established with any legal jurisdiction. Scriven stated:[1]

"Length of time being of the very essence of a manor, such things as receive their perfection by the continuance of time come not within the compass of the king's prerogative"

Effect of Quia Emptores

The effect of the statute of Quia Emptores (1290) was to make the creation of manors henceforward impossible, inasmuch as it enacted "that upon all sales and feoffments of land the feoffee shall hold the same, not of his immediate feoffor, but of the chief lord of the fee of whom such feoffor himself held it". The statute did not apply to a tenant-in-chief of the king, who might have alienated his land under a license. Accordingly, it is assumed that all existing manors are "of a date prior to the statute of Quia Emptores except perhaps some which may have been created by the king's tenants-in-chief with license from the crown".[2] When a great baron had granted out smaller manors to others, the seignory of the superior baron was frequently termed an honour.

Differentiated by legal status

All land was differentiated by its legal status and by physical characteristics. The basic forms of tenure were: Freehold, Copyhold, Customary Freehold and Leasehold. The legal status of land in England and Wales has been simplified such that only Freehold and Leasehold land remains (although, since 2002, a new category, Commonhold, also exists). In Ireland (Northern and Republic), only Freehold and Leasehold land remain.

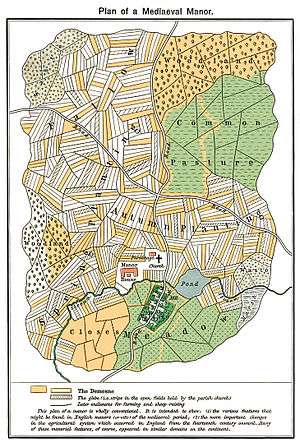

Constituent physical elements

- Demesne divided into:

- deer park, where the high and rare honour of a royal licence to empark had been obtained, usually restricted to great nobles or to the king's favoured courtiers, which enabled the lord to de-bar entry into the emparked area to other hunters, including to the king himself, who was accustomed to hunt several dozen square miles at a time with hundreds of hunt followers when on royal progresses around his kingdom. Horsemen would surround such large area in a funnel shape and all deer enclosed within would be systematically driven into large nets at the mouth of the funnel, to be slaughtered and later cooked and eaten by the king's huge retinue. Thus the lord of the manor would be able to enclose the licensed area by casting up an earthbank and hedge or a stone wall, both to preserve his own deer captive within, safe from predation and to prevent entry by others. Such arrangements frequently caused disputes amongst neighbouring lords and the annals record many instances of deliberate break-ins and breaking down of hedges for the purpose of exercising purported hunting-rights.

- pleasure garden, a later development.

- manor farm, home farm or barton, land retained "in-hand" by the lord of the manor, without sub-tenant and exploited for his own direct benefit by his own paid servants or manorial workforce, being chiefly, until later centuries, tenants-at-will (those with no tenancy rights) or those whose copyhold tenancies stipulated so many days per month or year to be worked on the demesne.

- Village, a settlement where most of the tenants lived, originally the villeins, tenants of the lord. The villa was the centre of the manor in Roman Britain.

- Cotts (or cottages) scattered individual small farmsteads occupied by the cottars, a superior class of tenants.

- Courthouse, in which manorial courts were held where a non-resident lord had no manor house and thus no great hall in which such business could be transacted by his steward. This was a common arrangement as many absentee lords held multiple manors and resided on only one permanently, or commuted between only two or three.

- Church land, the land on which was built the parish church. Originally part of the demesne land. Many surviving early mediaeval deeds record donations of land by lords to a local priory, perhaps one founded by their ancestors, for the purpose of establishing a parish church on. Sometimes an existing church was given by the lord to some favoured priory.[3] Parish churches were built and established by the original lords of each manor, in consultation with the bishop, out of self-interest, next to their manor houses, as being close to an institution which was believed to have direct access to an all-powerful god was clearly advantageous, perhaps even deemed essential for prosperity. Naves were added to the original buildings (which then became chancels) as parishioners began to require access also, usually built and maintained at the expense of the parishioners. Many such churches were built in time immemorial or pre-historic Celtic or later Anglo-Saxon times, thus the process of their establishment is not recorded. The Norman Conquest of 1066 obtained for King William ready-made and fully staffed "going concern" manors, income-producing businesses, and parish churches which had been established for centuries.

- Manorial chapels (or "manorial aisles") were built onto the sides of chancels of parish churches as the lord's household expanded, for the seating of the lord and his household at mass. He was thus seated in a private area out of direct view of his tenants occupying the nave, with its own private external entrance, and was near the high altar, the holiest place in the church, and was able to view the priest elevating the host, the holiest part of the mass, through a squint let into the intervening wall, if any. He and his family were buried under the floor of the manorial chapel, in dedicated vaults or under individual ledger stones, or in the chancel nearer the high altar itself, the position of greatest honour being to the immediate north of the high altar, a position frequently occupied by founder's tombs and their effigies or monuments. From the 17th century, the lord's family erected their mural monuments on the walls of the manorial chapel. The lords were responsible for the building costs and for financing the maintenance of the fabric of the manorial chapel, and this onerous clause is frequently found in their deeds by modern purchasers of manor houses. Today many such unaware purchasers are sued in law by the Church of England, owners today of the freeholds of most parish churches, for refusal to pay large repair bills for roofs of former manorial chapels.

- Glebe, land donated in fee at some time by a previous lord of the manor to the rectory for support of the rector (parson or parish priest). Each succeeding rector thus became effectively the life tenant. In addition to the produce from the glebe, the rector was entitled to tithes from the manor as a whole, in general one-tenth of all agricultural produce, due annually from all tenants of the manor, frequently delivered before the specified due date into the tithe barn, a large structure within the manor.

- Common land, by convention open land, over which the lord, certain manorial tenants, and other parishioners held shared rights. For example, grazing rights or a right of estovers (taking wood).

- Woodland, in which tenants might have the right to pannage (feeding swine on acorns).

- Corn-mill, usually situated by a stream and driven by water power, at which tenants were obliged to grind their corn into flour, thus providing a further revenue stream for the lord, who had a captive customer base. They were thus forbidden from grinding at the mill within any other manor.

- Freehold. Such "free-tenants" or "free men" had a duty to attend and sit as jury on the lord's manorial court, presided over by himself, or if an absentee lord, by his steward. Apparently not subject to the jurisdiction of the manorial court. Disputes between a lord and his freeholders were held in the county court, presided over by the Sheriff of the county.

- Copyhold, the text of which tenancy agreement was recorded only in the manorial roll, which therefore had to be consulted in case of dispute. Subject to the jurisdiction of the manorial court.

- Customary Freehold (between the two)

- Leasehold (granted for a term, usually one of years or a number of lives not exceeding three, or the longer of either period); the Reversion (also known as Reversionary Freehold Interest or Freehold Reversion), at the end of the term or in case of escheat or forfeiture, is the prospective property of the lord of the manor.

Differentiated by physical character

- Arable, ploughed land used to grow crops.

- Waste, economically unproductive land.

- Pasture, grassland used for grazing livestock in the summer.

- Meadow, grassland set aside for making hay for winter fodder.

- Closes, small enclosed fields closed-off by the erection of earth-banks, hedges or stone wall boundaries, used for example to house ewes with their lambs requiring close observation, and for rotational pasture management, reducing parasite infestation and keeping grass fresh.

- Marsh, a possible source of reed for thatching of roofs.

- Woodland, an essential fuel and building resource. Also used for pannage.

- Furze, a highly flammable fuel resource used by the lower tenants.

- Fallow, land resting within the cycle of crop rotation agriculture.

- Fishpond, for inland manors, used to breed and store fish such as carp for eating on Fridays when the eating of meat was prohibited by religious custom.

- Quarry, a source of building stone and of lime for burning to create mortar and fertiliser.

Officers

A manor was akin to the modern firm or business or other going concern. It was a productive unit, which required physical capital, in the form of land, buildings, equipment and draught animals such as ploughing oxen and labour in the form of direction, day-to-day management and a workforce. It was further similar in that its ownership could be transferred, with the necessary "licence to alienate" having been obtained from the overlord, as can the ownership of a modern company. The administration was self-contained and the new lord needed only to collect its net revenues to form his return on investment. The direction was ultimately provided by the manorial court, presided over by the lord's personal steward, whose members included the freehold tenants of the manor. The court itself appointed most of the lower manorial officers, which included the following:

- Bailiff, in charge of supervising the cultivation of the manor.

- Reeve, an overseer.

- Ditch Reeve, responsible for maintaining drainage ditches.

The efficiency, productivity and thus profitability of a manor, therefore, depended on a mixture of qualities and interaction of location, micro-climate, natural resources, soil type, direction and labour. It was in the interest of all dwellers within the manor, to a greater or lesser degree, that it should be successful.

Jurisdiction

The manorial court had wide legal jurisdiction over the inhabitants of the manor, sometimes with the right to administer capital punishment, if the lord had obtained from the king the right of holding a court leet. Much of the law was specific to a particular manor, as developed by "custom of the manor" and as interpreted by the manorial court. Rights of appeal existed to the hundred court and the county court beyond that over which presided the county's sheriff.

Free manor

A free manor was an autonomous area, outside the jurisdiction, law and administrative control of the surrounding territory.[4]

Membership

Every person who lived in medieval England was regarded as a member of a manor and was under the jurisdiction of a manorial court, unless a citizen of a borough (in certain generally urban towns), or a cleric, or a lord of the manor himself, or (failing sons) an heiress lady of the manor herself, who were subject to the primary jurisdiction of the king's court, if a tenant-in-chief, or of the county court, if a mesne (intermediate) lord. It was not permissible for a man to migrate from the manor of his birth except by arrangement with its authorities. The manor was typically, via its vestry, also the source of a needy family's charitable relief, which was at the discretion of the manorial court, according to the custom of each manor. An alien within a manor would not, therefore, be automatically entitled to any relief or protection (such as parish constables) offered by the lord to prevent crime. Merchants and travellers were in general only safe in travelling with costly hired protection or with protection in place from a local sheriff, particularly in remote and sparsely populated areas. Even in 1822, the book Rural Rides refers to frequent instances of robbery in rural areas.[5]

Residents of a manor

- Lord of the manor (often absent), or an absentee (never resident)

- Serfs

- Villeins

- Cottars

- Bordars

- Freeholders

- Copyholders

Current legal status

Overlap with parish

Any parish which is among the bulk formed in the medieval period (whether town or village, but not in old cores of cities) tended to share its name with the manor (which may or may not exist today). Such non-borough parishes have clerical jurisdiction over the same geographic territory over which the Lord had jurisdiction through his manorial court.

The parish generally came into existence after the establishment of the manor, following the building of a church by the Lord of the Manor for the use of himself and his tenants, perhaps in consultation with the bishop within whose clerical jurisdiction the manor was situated.[6] He gave permanently the parish church some of his land, the revenues from which thus were to support the priest and the maintenance of the church building. The lord of the manor retained the advowson, that is the right to select and appoint the parish priest, yet the parish was governed by the diocese within which it was situated, which also granted it the tithes to which it was legally entitled, which was a tax of one tenth of the produce of the manor. Outlying parts of many manors over time were forcibly lost by judgment or attainder by the sovereign, exchanged between neighbouring lords or sold to pay debts, and thus would change owner, but would almost never change parish.

As, over time, a manor's lands could grow and shrink (they could extend over several different parishes), many manors became virtually worthless and lost any pretence of having a lord or became entirely subsumed by another. Others could arise by the principal lord's special grant, approved by the sovereign of subinfeudation.

See also

- Manorialism

- Walter of Henley, a 13th-century writer on agricultural management of a manor.

- Maenor, the (etymologically-unrelated) Welsh equivalent

- Fazenda, the Brazilian equivalent

- Hacienda or Señorío, the Spanish equivalent

Notes

- Scriven, John, (Serjeant at law), A treatise on copyhold, customary freehold, and ancient demesne tenure: with the jurisdiction of Courts baron and Courts leet; also an appendix, containing rules for holding Customary courts, Courts baron and Courts leet, forms of court rolls, deputations, and copyhold assurances, and extracts from the relative acts of Parliament, 2 vols., 2nd. ed., London, 1823, vol.1, chap. 1

- Williams, Real Property, chap. 4; See also Scriven, Copyholds, chap 1

- For example Molland Church in Devon was given by the lord of the manor in the 12th century to Hartland Abbey

- Across the open field: essays drawn from English landscapes, page 101 Laurie Olin, published 2000, ISBN 978-0-8122-3531-9, accessed 2011-10-17

- Rural Rides Volume i. THROUGH HAMPSHIRE, BERKSHIRE, SURREY, AND SUSSEX, BETWEEN 7TH OCTOBER AND 1ST DECEMBER, 1822 (ed. Everyman) William Cobbett, p 124

- Domesday Map listing all Domesday Book entries - Thorncroft Retrieved 2013-09-30

References

- Bennett, H.S., Life on the English Manor, Cambridge, 1937

- Encyclopædia Britannica, 9th Edition, Volume 15, pp. 496–497, "Manor". Some text from this source now in the public domain is contained in this article.

- Jerrold, D., Introduction to the History of England, 1949 (Source for Everyman's Encyclopaedia, 5th Edition, vol. 8, "Manor")

- Lewis, C. P., 'The Invention of the Manor in Norman England', in Bates, David, Anglo-Norman Studies 34: Proceedings of the Battle Conference 2011, Boydell & Bewer, 2012, pp. 123–150. ISBN 9781846159718

- Vinogradoff, Sir P., Growth of the Manor, 1951