Haliotis

Haliotis, common name abalone (US), paua (NZ), or ormer (UK), is the only genus in the family Haliotidae.[2]

| Haliotis | |

|---|---|

| Living abalone in tank showing epipodium and tentacles, anterior end to the right. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Gastropoda |

| Clade: | Vetigastropoda |

| Clade: | Lepetellida |

| Superfamily: | Haliotoidea |

| Family: | Haliotidae |

| Genus: | Haliotis Linnaeus, 1758 |

| Type species | |

| Haliotis asinina | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

This genus once contained six subgenera. These subgenera have become alternate representations of Haliotis.[2] The genus consists of small to very large, edible, herbivorous sea snails, marine gastropod molluscs. The number of species recognized worldwide ranges between 30[3] and 130,[4] with over 230 species-level taxa described. The most comprehensive treatment of the family considers 56 species valid, with 18 additional subspecies.[5]

Description

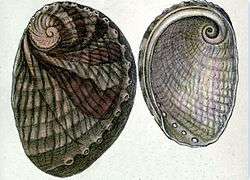

The shells of abalones have a low, open, spiral structure, and are characterized by having several open respiratory pores in a row near the shell's outer edge. The thick inner layer of the shell is composed of nacre, which in many species of abalone is highly iridescent, giving rise to a range of strong, changeable colors, which make the shells attractive to humans as decorative objects, in jewelry, and as a source of colorful mother-of-pearl.

The shell of abalones is convex, rounded to oval shape, and may be highly arched or very flattened. The shell of the majority of species is ear-shaped, presenting a small, flat spire and two to three whorls. The last whorl, known as the body whorl, is auriform, meaning that the shell resembles an ear, giving rise to the common name "ear shell". Haliotis asinina has a somewhat different shape, as it is more elongated and distended. The shell of Haliotis cracherodii cracherodii is also unusual as it has an ovate form, is imperforate, shows an exserted spire, and has prickly ribs.

A mantle cleft in the shell impresses a groove in the shell, in which are the row of holes (known as tremata), characteristic of the genus. These holes are respiratory apertures for venting water from the gills and for releasing sperm and eggs into the water column. They make up what is known as the selenizone which forms as the shell grows. This series of eight to 38 holes is near the anterior margin. Only a small number are generally open. The older holes are gradually sealed up as the shell grows and new holes form. Therefore, the number of tremata is not characteristic for the species. Each species has a number of open holes, between four and 10, in the selenizone. This number is not fixed and can vary within a species and between populations. Abalones have no operculum. The aperture of the shell is very wide and nacreous.

The exterior of the shell is striated and dull. The color of the shell is very variable from species to species, which may reflect the animal's diet.[6] The iridescent nacre that lines the inside of the shell varies in color from silvery white, to pink, red and green-red, to deep blue, green to purple.

The animal shows fimbriated head-lobes. The side-lobes are also fimbriated and cirrated. The rounded foot is very large. The radula has small median teeth, and the lateral teeth are single and beam-like. About 70 uncini are present, with denticulated hooks, the first four very large. The soft body is coiled around the columellar muscle, and its insertion, instead of being on the columella, is on the middle of the inner wall of the shell. The gills are symmetrical and both well developed.[7]

These snails cling solidly with their broad muscular foot to rocky surfaces at sublittoral depths, although some species such as Haliotis cracherodii used to be common in the intertidal zone. Abalones reach maturity at a relatively small size. Their fecundity is high and increases with their size (from 10,000 to 11 million eggs at a time). The spermatozoa are filiform and pointed at one end, and the anterior end is a rounded head.[8]

The larvae are lecithotrophic. The adults are herbivorous and feed with their rhipidoglossan radula on macroalgae, preferring red or brown algae. Sizes vary from 20 mm (0.79 in) (Haliotis pulcherrima) to 200 mm (7.9 in), while Haliotis rufescens is the largest of the genus at 12 in (30 cm).[9]

By weight, about one-third of the animal is edible meat, one-third is offal, and one-third is shell.

Structure and properties of the shell

The shell of the abalone is exceptionally strong and is made of microscopic calcium carbonate tiles stacked like bricks. Between the layers of tiles is a clingy protein substance. When the abalone shell is struck, the tiles slide instead of shattering and the protein stretches to absorb the energy of the blow. Material scientists around the world are studying this tiled structure for insight into stronger ceramic products such as body armor.[10] The dust created by grinding and cutting abalone shell is dangerous; appropriate safeguards must be taken to protect people from inhaling these particles.

Species

The number of species that are recognized within the genus Haliotis has fluctuated over time, and depends on the source that is consulted. The number of recognized species ranges from 30[3] to 130.[4] This list finds a compromise using the "WoRMS" database, plus some species that have been added, for a total of 57.[2][11] The majority of abalone have not been evaluated for conservation status. Those that have been reviewed tend to show that the abalone in general is declining in numbers, and will need protection throughout the globe.

| Species | Range | Conservation status |

|---|---|---|

| Haliotis alfredensis Bartsch, 1915[nb 1] | South Africa | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis arabiensis Owen, Regter & Van Laethem, 2016 | Off Yemen and Oman | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis asinina Linnaeus, 1758 | Philippines; Indonesia; Australia; Japan; Thailand; Vietnam | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis australis Gmelin, 1791 | New Zealand | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis brazieri Angas, 1869 | Eastern Australia | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis clathrata Reeve, 1846 | Seychelles; Comores; Madagascar; Mauritius; Kenya | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis coccoradiata Reeve, 1846 | Eastern Australia | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis corrugata Wood, 1828 | California, USA; Baja California, Mexico | Species of Concern National Marine Fisheries Service;[14] Vulnerable (global) and imperiled (California) California Department of Fish and Wildlife[15] |

| Haliotis cracherodii Leach, 1814 | California, USA; Baja California, Mexico | CR IUCN;[16] Vulnerable(Global, Nation: US, State: California) California Department of Fish and Wildlife;[15][17] Listed endangered National Marine Fisheries Service[18] |

| Haliotis cyclobates Péron & Lesueur, 1816 | Southern Australia | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis dalli Henderson, 1915 | Galapagos Islands | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis discus Reeve, 1846 | Japan; South Korea | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis dissona (Iredale, 1929) | Australia; New Caledonia | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis diversicolor Reeve, 1846 | Japan; Australia; Southeast Asia | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis drogini Owen & Reitz, 2012 | Not evaluated | |

| Haliotis elegans Koch & Philippi, 1844 | Western Australia | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis exigua Dunker, R.W., 1877 | Japan | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis fatui Geiger, 1999 | Tonga Mariana Islands | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis fulgens Philippi, 1845 | California, USA; Baja California, Mexico | Vulnerable (Global, State: California California Department of Fish and Wildlife);[15] Species of Concern NMFS[19] |

| Haliotis geigeri Owen, 2014 | Not evaluated | |

| Haliotis gigantea Gmelin, 1791 | Japan | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis glabra Gmelin, 1791 | Philippines; Vietnam | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis iris Gmelin, 1791 | New Zealand; Vanuatu | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis jacnensis Reeve, 1846 | Japan; Nicobar Islands; Ryukyu Islands; Pacific Islands; | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis kamtschatkana Jonas, 1845 | Western North America | Endangered IUCN;[20] Imperiled (Alaska, British Columbia), Vulnerable (global, US), critically imperiled (California);[15][21] Species of Concern NMFS[22] |

| Haliotis laevigata Donovan, 1808 | South Australia; Tasmania | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis madaka (Habe, 1977) | Japan; South Korea | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis mariae Wood, 1828 | Oman; Yemen | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis marmorata Linnaeus, 1758 | Liberia; Ivory Coast; Ghana | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis (Marinauris) matihetihensis (Eagle, 1999) | † | |

| Haliotis melculus (Iredale, 1927) | Australia (New South Wales, Queensland) | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis midae Linnaeus, 1758 | South Africa | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis mykonosensis Owen, Hanavan & Hall, 2001 | Greece; Turkey; Tunisia | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis ovina Gmelin, 1791 | Thailand; Vietnam; southern part of the Pacific Ocean; Andaman Islands; Maldives; Ryukyu Islands | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis parva Linnaeus, 1758 | South Africa; Angola | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis planata G. B. Sowerby II, 1882 | Ryukyu Islands; Sri Lanka; Indonesia; Fiji; Andaman Sea | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis pourtalesii Dall, 1881 | Gulf of Mexico; Eastern South America; northern Colombia | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis pulcherrima Gmelin, 1791 | Polynesia | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis queketti E.A. Smith, 1910 | South Africa; Mozambique; Kenya | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis roei Gray, 1826 | Australia | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis rubiginosa Reeve, 1846 | Lord Howe Island; Malakula Island | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis rubra Leach, 1814 | Southern and Eastern Australia | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis rufescens Swainson, 1822 | Western North America | Apparently secure (global, US); critically imperiled (Canada)[23] |

| Haliotis rugosa Lamarck, 1822 | South Africa; Madagascar; Mauritius; Red Sea | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis scalaris (Leach, 1814) | Southern and Western Australia | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis semiplicata Menke, 1843 | Western Australia | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis sorenseni Bartsch, 1940 | California, USA; Baja California, Mexico | Critically imperiled (global, US, California);[15][24] Endangered NMFS[25] |

| Haliotis spadicea Donovan, 1808 | South Africa | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis speciosa Reeve]], 1846 | Eastern South Africa | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis squamosa Gray, 1826 | Madagascar; Eastern Australia; Okinawa | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis stomatiaeformis Reeve, 1846 | Malta; Pacific Islands | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis supertexta Lischke, 1870 | Japan; Sao Tome | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis thailandis Dekker & Patamakanthin, 2001 | Andaman Sea | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis tuberculata Linnaeus, 1758 | Ireland (introduced); Channel Islands; Azores; Canary Islands; Japan; Madeira ; Brittany; Great Britain | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis unilateralis Lamarck, 1822 | Gulf of Aqaba; East Africa; Seychelles; | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis varia Linnaeus, 1758 | Mascarene Basin; Red Sea; Sri Lanka; Western Pacific; | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis virginea Gmelin, 1791 | New Zealand; Chatham Islands; Auckland Islands; Campbell Island; Fiji | Not evaluated |

| Haliotis walallensis Stearns, 1899 | Western North America | Not evaluated |

_S01.jpg) A dorsal view of a live ass's ear abalone, Haliotis asinina

A dorsal view of a live ass's ear abalone, Haliotis asinina the pink abalone, Haliotis corrugata

the pink abalone, Haliotis corrugata- The black abalone, Haliotis cracherodii

Dorsal (left) and ventral (right) views of the blacklip abalone, Haliotis rubra

Dorsal (left) and ventral (right) views of the blacklip abalone, Haliotis rubra The white abalone, Haliotis sorenseni

The white abalone, Haliotis sorenseni A shell of Haliotis varia form dohrniana

A shell of Haliotis varia form dohrniana

- Haliotis discus discus

- Haliotis fulgens fulgens

- Haliotis gigantea f. sieboldii

- Haliotis kamtschatkana assimilis (South California).

- Haliotis laevigata (South Australia).

_(Quinn's_Rocks%2C_Western_Australia)_1_(23565526643).jpg)

_(South_Africa)_3_(24139744761).jpg)

- Haliotis tuberculata (Europe)

Synonyms

See also

References

- Geiger & Groves 1999, p. 872

- Gofas, Tran & Bouchet 2014

- Dauphin et al. 1989, p. 9

- Cox 1962, p. 8

- D.L., Geiger (1999). "Distribution and biogeography of the recent Haliotidae (Gastropoda: Vetigastropoda) world-wide". Bollettino Malacologico.

- Beesley, Ross & Wells 1998

- Tryon, Jr. 1880, p. 41

- Tryon, Jr. 1880, p. 46

- Hoiberg 1993, p. 7

- Lin & Meyers 2005, p. 27 & 38

- Abbott & Dance 2000

- Tran & Bouchet 2009

- EoL 2014

- Neuman 2007

- State of California 2011

- Smith, Stamm & Petrovic 2003

- Anon 2014f

- Anon 2009

- Neuman 2009

- McDougall, Ploss & Tuthill 2006

- Anon 2014c

- Gustafson & Rumsey 2007

- Anon 2014d

- Anon 2014e

- Anon 2001

- Linnaeus, C. 1758. Systema Naturae per Regna tria Naturae, secundem Classes, Ordines, Genera, Species, cum Characteribus, Differentis, Synonymis, Locis. Tom.1 Editio decima, reformata. Holmiae : Laurentii Salvii 824 pp.

- Iredale, T. 1927. Caloundra Shells. The Australian Zoologist 4: 331-336, pl. 46

- Iredale, T. 1929. Queensland molluscan notes, No. 1. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 9(3): 261-297, pls 30-31

- Cotton, B.C. & Godfrey, F.K. 1933. South Australian Shells. Part 9. South Australian Naturalist 15(1): 14-24

- Cotton, B.C. 1943. Australian Shells of the Family Haliotidae. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia 67(1): 175-180

- Moore, R.C. (ed.) 1960. Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. Part I. Mollusca 1. Boulder, Colorado & Lawrence, Kansas : Geological Society of America & University of Kansas Press xxiii + 351 pp.

- Wilson, B. 1993. Australian Marine Shells. Prosobranch Gastropods. Kallaroo, Western Australia : Odyssey Publishing Vol. 1 408 pp.

- Geiger, D.L. & Poppe, G.T. 2000. A Conchological Iconography. The family Haliotidae. Germany : ConchBooks 135 pp.

- Bouchet, P.; Gofas, S. (2014). Haliotis Linnaeus, 1758. Accessed through: World Register of Marine Species at http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=138050 on 2014-08-21f