Hakka hill song

Hakka hill songs (Chinese: 客家山歌; pinyin: Kèjiā shāngē; Hakka: [hak˥ka˦ san˦ kɔ˦]) are rural songs sung in the Hakka language by the Hakka people. They are probably one of the better known elements that reflect Hakka culture, regarded by many as the 'pearl of Hakka Literature'.[1]

| Music of China | |

|---|---|

| |

| General topics | |

| |

| Genres | |

| Specific forms | |

| Media and performance | |

| Music festivals | Midi Modern Music Festival |

| Music media |

|

| Nationalistic and patriotic songs | |

| National anthem | |

| Regional music | |

Hakka hill songs vary in theme from love to personal conduct. In the past, they are said to have been used as a method of courting between young men and women. The songs are also used as a form of communication at a distance. Since Hakka people mostly live in hilly areas, song is used as a better means of communication than spoken words. The melody of Hakka hill songs tend to have higher pitch so the sound can travel farther.

They can be made up impromptu as a means to communicate with others or to express oneself. The lyrics can also be made to contain riddles, as a game or a more competitive nature. The challenger will answer the riddle in the form of song of similar melody.

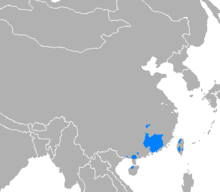

They are popular in Meizhou Prefecture in the northeastern part of Guangdong Province, the western part of Fujian Province, the southern part of Jiangxin Province and the northern part of Taiwan, places where the Hakka live. The Moiyen (Meixian) county, home to many Hakkas in Guangdong, hold Hakka hill songs competitions inviting Hakka competitors from all over China to participate.

History

The original composers of Hakka hill songs can be difficult to find out as the songs, being a kind of oral literature, have been widespread and orally passed from generation to generation. The tradition, however, most likely originated from Classic of Poetry (The Book of Songs), which influenced Chinese literature for thousands of years.[2] Other than its original influence, Hakka hill songs had continually developed during the migration of the Hakka. Many different cultures during their migration have influenced these songs, such as the cultures of Wu State and Chu State, as well as the culture of the She peoples and the Yao peoples.[2]

The long Hakka migration finally ended during the Ming and Qing dynasties, and the Hakka settled in the mountainous area of South Central China between Jiangxi, Guangdong and Fujian provinces. It was further influenced by the daily work of the Hakka on the mountainside: mountain singing was a way to socialise with one another and to alleviate the pain of hard work. The singing was at one point suppressed by an official ban from the government of the Qing Dynasty. However, despite the ban, mountain songs were often sung in secret, carrying a rebellious spirit between the lines, even though outwardly most of the songs were seemingly only about everyday topics such as love and labouring in the fields.[3]

Types and characteristics

The melody of Hakka hill songs vary from area to area since the Hakka are widely spread in different regions of China and their dialect they speak differs in many respects. For example, the Mei County, a well-known Hakka area in Guangdong Province once had several unique tunes in this region, never to mention about the different tunes in other areas of Guangdong such as Xingning, Wuhua, Dabu, Fengshun, Jieyang, Zijin, Heyuan, Huiyang and others in the north and west of Guangdong. Due to this phenomenon, this type of singing can also be referred as the Jiu Qiang Shi Ba Diao (Chinese: 九腔十八調; pinyin: Jiǔ qiāng shíbā diào; lit.: 'nine airs eighteen tunes').

The so-called nine airs are the Hailu, Sixian, Raoping, Fenglu, Meixian, Songkou, Guangdong, Guangnan and Guangxi air. Likewise, the eighteen tunes are the Pingban, Shangezi, Laoshange (also the South Wind tune), Siniange, Bingzige, Shibamo, Jianjianhua (also the Ancients in December tune), Chuyizhao, Taohuakai, Shangshancaica, Guanziren, Naowujin, Songjinchai, Dahaitang, Kuliniang, Xishoujin, Tiaomaijiu, Taohuaguodu (also the Chengchuange tune) and Xiuxiangbao tune. However, there are actually more tunes than aforementioned, but the others are not recorded and so remain unknown.

Despite all of the differences between their tunes, Hakka hill songs share a common feature which is that one Hakka hill song can be sung by any Hakka from other regions. There is no rigid rule of singing skills and the length of the tune depends on the singer's own arrangement.[4] Hakka hill songs incorporate seventeen types of Hakka flat intonation and seven more types of oblique intonation. Each stanza consists of four lines, each with seven syllables and each line except the third often include flat intonation.[5]

Example

This poem, titled A Girl with Her Three-Year-Old Husband, tells a story about a girl who was born on the outskirts of Meizhou town, suffering due to an arranged marriage. She was sold to a family at a very young age and had to marry her then-future mother-in-law's son she gave birth to when the girl was sixteen years old. The son was three years old by the time the girl turned eighteen years of age, and at that time it agonised her having to sleep with her future husband. The first stanza quotes to what she sang on one night about that resentment.

The second stanza is the reply from one of her neighbours, an old lady who heard what the girl had sung that night. The final stanza is the immediate response from the girl who then became even more begrudged after hearing the lady's words, which then deeply moved the old lady as she herself felt very sorry for the girl's suffering:[6]

三歲老公鬼釘筋,

睡目唔知哪頭眠,

夜夜愛涯兜屎尿,

硬想害我一生人。

隔壁侄嫂你愛賢,

帶大丈夫十把年,

初三初四娥眉月,

十五十六月團圓。

隔壁叔婆你愛知,

等郎長大我老哩,

等到花開花又謝,

等到滿月日落西。

- Translation

Little three-year-old husband,

sleeping carelessly on the bed,

every night I have to serve him,

and he is ruining my whole life.

You shall become wise, my dear girl,

you husband shall by ten years grow,

and the waning moon on the early part of each month,

will be a full moon by the fifteenth and sixteenth days.

You know, my dear aunt,

when that boy grows up, I too shall grow old,

the flower is blooming and the other has withered away,

the full moon has risen and the sun has fallen.

References

- Zhang, Kuaicai; Huang, Dongyang (August 2012). "The Study of the Birth of Hakka Hill Songs". Beijing Music Magazine Editing Department (in Chinese). Beijing (8).

- Zhong, Junkun (2009). The Cultural Study of Hakka Hill Songs (in Chinese). Harbin: Heilongjiang People's Publishing House. pp. 10–11.

- Tse-Hslung, Lin (2011). "Mountain Songs, Hakka Songs, Protest Songs: A Case Study of Two Hakka Singers from Taiwan". Asian Music. 42 (1): 94–95. ProQuest 847645029.

- Niu Lang (1957). "Love Songs of the Hakka in Kwangtung". Folklore and Folk Literature Series of National Peking University and Chinese Association of Folklore. The Orient Cultural Service: 1–2.

- Chen, Jufang (September 2008). Natural Music, Guangdong Hakka Hill Songs (in Chinese). Guangzhou: Flower City Publishing House. p. 88.

- Luo, Yingxiang (October 1994). "Overseas Hakkas" (in Chinese). Kaifeng: Henan University Press: 285. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)