HMS Pandora (1779)

HMS Pandora was a 24-gun Porcupine-class sixth-rate post ship of the Royal Navy launched in May 1779.[1] She is best known as the ship sent in 1790 to search for the Bounty mutineers. The Pandora was partially successful by capturing 14 of the mutineers, but was wrecked on the Great Barrier Reef on the return voyage in 1791.[2] The Pandora is considered to be one of the most significant shipwrecks in the Southern Hemisphere.[3]

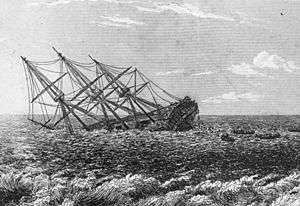

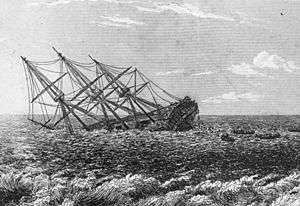

HMS Pandora in the act of foundering 29 August 1791 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | HMS Pandora |

| Ordered: | 11 February 1778 |

| Builder: | Adams & Barnard, Grove Street shipyard, Deptford |

| Laid down: | 2 March 1778 |

| Launched: | 17 May 1779 |

| Completed: | 3 July 1779 at Deptford Dockyard |

| Commissioned: | May 1779 |

| Fate: | Wrecked on 28 August 1791 in the Torres Strait. |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | 24-gun Porcupine-class sixth-rate post ship |

| Tons burthen: | 524 (bm) |

| Length: |

|

| Beam: | 32 ft 3 in (9.83 m) |

| Draught: |

|

| Depth of hold: | 10 ft 3 in (3.12 m) |

| Sail plan: | Full-rigged ship |

| Complement: | 160 (140 by 1815) |

| Armament: |

|

Early service

Her first service was in the Channel during the 1779 threatened invasion by the combined fleets of France and Spain. She was deployed in North American waters during the American War Of Independence and saw service as a convoy escort between England and Quebec. On 18 July 1780, while under the command of Captain Anthony Parry, she and Danae captured the American privateer Jack.[4] Then on 2 September, the two British vessels captured the American privateer Terrible.[5] On 14 January Pandora captured the brig Janie. Then on 11 March she captured the ship Mercury.[6] Two days later Pandora and HMS Belisarius were off the Capes of Virginia when they captured the sloop Louis, which had been sailing to Virginia with a cargo of cider and onions.[7] Under Captain John Inglis Pandora captured more merchant vessels. The first was the brig Lively on 24 May 1782.[8] More followed: the ship Mercury and the sloops Port Royal and Superb (22 November 1782), the brig Nestor (3 February 1783), and the ship Financier (29 March).[9] At the end of the American war the Admiralty placed Pandora in ordinary (mothballed) in 1783 at Chatham for seven years.

Voyage in search of the Bounty

Pandora was ordered to be brought back into service on 30 June 1790 when war between England and Spain seemed likely due to the Nootka Crisis. However, in early August 1790, 5 months after learning of the mutiny on HMS Bounty, the First Lord of the Admiralty, John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham, decided to despatch her to recover the Bounty, capture the mutineers, and return them to England for trial.[10] She was refitted, and her 9-pounder guns were reduced to 20 in number, though she gained four 18-pounder carronades.

Pandora sailed from The Solent on 7 November 1790, commanded by Captain Edward Edwards and manned by a crew of 134 men. With his crew was Thomas Hayward, who had been on the Bounty at the time of the mutiny, and left with Bligh in the open boat. At Tahiti they were also assisted by John Brown, who had been left on the island by an English merchant ship, The Mercury.[11]

Unknown to Edwards, twelve of the mutineers, together with four crew who had stayed loyal to Bligh, had by then already elected to return to Tahiti, after a failed attempt to establish a colony (Fort St George) under Fletcher Christian's leadership on Tubuai, one of the Austral Islands. The disaffected men were living in Tahiti as 'beachcombers', many of them having fathered children with local women. Fletcher Christian's group of mutineers and their Polynesian followers had sailed off and eventually established their settlement on the then uncharted Pitcairn Island. By the time of Pandora's arrival, fourteen of the former Bounty men remained on Tahiti, Charles Churchill having been murdered in a quarrel with Matthew Thompson, who was in turn killed by Polynesians, who considered Churchill their king.[12]

The Pandora reached Tahiti on 23 March 1791 via Cape Horn. Three men came out and surrendered to Edwards shortly after Pandora's arrival. These were Joseph Coleman, the Bounty's armourer, and Peter Heywood and George Stewart, midshipmen.[11] Edwards then dispatched search parties to round up the remainder. Able Seaman Richard Skinner was apprehended the day after Pandora's arrival. By now alerted to Edwards' presence, the other Bounty men fled to the mountains while James Morrison, Charles Norman and Thomas Ellison, tried to reach the Pandora to surrender in the escape boat they had built. All were eventually captured, and brought back to Pandora on 29 March.[13] An eighth man, the half blind Michael Byrne, who had been fiddler aboard Bounty, had also come aboard by this time. It was not recorded whether he had been captured or had handed himself in.[13] Edwards conducted further searches over the next week and a half, and on Saturday two more men were brought aboard Pandora, Henry Hilbrant and Thomas McIntosh. The remaining four men, Thomas Burkett, John Millward, John Sumner and William Muspratt, were brought in the following day.[14] These fourteen men were locked up in a makeshift prison cell, measuring eleven-by-eighteen feet, on the Pandora's quarter-deck, which they called "Pandora's Box".[15]

On 8 May 1791 the Pandora left Tahiti and subsequently spent three months visiting islands in the South-West Pacific in search of the Bounty and the remaining mutineers, without finding any traces of the pirated vessel. During this part of the voyage fourteen crew went missing in two of the ship's boats. Nine of them were on the Matavy, a schooner built by Bounty crew members and called by them Resolution. It had been commandeered to serve as a ship's tender but lost sight of Pandora near Tutuila at night. By chance, during their voyage to Batavia these nine became the first Europeans to make contact with the people of Fiji.[16] [17]

In the meantime the Pandora visited Tokelau, Samoa, Tonga and Rotuma. They also passed Vanikoro Island, which Edwards named Pitt's Island; but they did not stop to explore the island and investigate obvious signs of habitation. If they had done so, they would very probably have discovered early evidence of the fate of the French Pacific explorer La Perouse's expedition which had disappeared in 1788. From later accounts about their fate it is evident that a substantial number of crew survived the cyclone that wrecked their ships Astrolabe and Boussole on Vanikoro's fringing reef.

Wrecked

by Robert Batty

Heading west, making for the Torres Strait, the ship ran aground on 29 August 1791 on the outer Great Barrier Reef. She sank the next morning, claiming the lives of 35 men - 31 crew and 4 of the mutineers.[18] The four prisoners lost were George Stewart; John Sumner; Richard Skinner; and Henry Hillbrandt (according to one history they drowned because their hands were still manacled; James Morrison's hands were also manacled but he survived.)[19][20]; The remainder of the ship's company (89 crew and 10 prisoners, 7 of whom were released from their cell as the ship sank) assembled on a small treeless sand cay. After two nights on the island they sailed for Timor in four open boats, making a stop on Muralag (Prince of Wales Island) in the Torres Strait seeking fresh water.[21] They arrived in Kupang on 16 September 1791 after an arduous voyage across the Arafura Sea. Sixteen more died after surviving the wreck, many having fallen ill during their sojourn in Batavia (Jakarta). Eventually only 78 of the 134 men who had been on board upon departure returned home.

Captain Edwards and his officers were exonerated for the loss of the Pandora after a court martial. No attempt was made by the colonial authorities in New South Wales to salvage material from the wreck. The ten surviving prisoners were also tried; the various courts martial held acquitted four of those of mutiny and, although the other six were convicted, three were executed - Millward, Burkitt and Ellison who were executed on 29 October 1792 on board the man-of-war Brunswick at Portsmouth.[22] Peter Heywood and James Morrison received a Royal pardon, while William Muspratt was acquitted on a legal technicality.

Descendants of the nine mutineers not discovered by Pandora still live on Pitcairn Island, the refuge Fletcher Christian founded in January 1790 and where they burnt and scuttled the Bounty a few weeks after arrival. Their hiding place was not discovered until 1808 when the New England sealer Topaz (Captain Mayhew Folger) happened on the tiny uncharted island. By then, all of the mutineers – except John Adams (aka Alexander Smith) – were dead, most having died under violent circumstances.

Wreck site: discovery and archaeology

The wreck of the Pandora is located approximately 5 km north-west of Moulter Cay 11°23′S 143°59′E on the outer Great Barrier Reef, on the edge of the Coral Sea. It is one of the best preserved shipwrecks in Australian waters.[23] Its discovery was made on 15 November 1977 by independent explorers Ben Cropp, Steve Domm and John Heyer.[23][24]

John Heyer, an Australian documentary film maker, had predicted the position of the wreck based on his research in the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich. His discovery expedition was launched with the help of Steve Domm, a boat owner and naturalist, and the Royal Australian Air Force. Using the built-in sensors of the RAAF P-2V Neptune, the magnetic anomaly caused by the wreck was detected and flares were laid down near the coordinates predicted by John Heyer.

Ben Cropp, an Australian television film maker, gained knowledge of Heyer's expedition and decided to launch his own search with the intention of following Heyer by boat; In this way Ben Cropp found the Pandora wreck just before John Heyer's boat did. The wreck was actually sighted by a diver called Ron Bell on Ben Cropp's boat. After the wreck site was located it was immediately declared a protected site under the Australian Historic Shipwrecks Act 1976, and in 1978 Ben Cropp and Steve Domm shared the $10,000. reward for finding the wreck.

The Queensland Museum excavated the wreck on nine occasions between 1983 and 1999, according to a research design devised by marine archaeologists at the West Australian and Queensland museums (Gesner, 2016:16). Archaeologists, historians and scholars at the Museum of Tropical Queensland, Townsville, continue to piece together the Pandora story, using archaeological and extant historical evidence. A large collection of artefacts is on display at the museum.

In the course of the nine seasons of excavation during the 1980s and 1990s, the museum's marine archaeological teams established that approximately 30% of the hull is still intact (Gesner, 2000:39ff). The vessel came to rest at a depth of between 30 and 33 m on a gently sloping sandy bottom, slightly inclined to starboard; consequently more of the starboard side has been preserved than the port side of the hull. Approximately one third of the seabed in which the wreck is buried has been excavated by the Queensland Museum, leaving approximately 350 m³ for any future excavations.

Legacy

A pub in Restronguet Creek, Mylor Bridge, Cornwall, that dates to the 13th century was re-named "The Pandora Inn" in honour of HMS Pandora.[25]

Citations

- McKay, John; Coleman, Ron (1992). The 24-gun frigate 'Pandora' 1779. London: Conway Maritime Press.

- Gesner, Peter (1997). "HMS Pandora". In Delgado, James P. (ed.). Encyclopaedia of Underwater and Maritime Archaeology. London: British Museum Press. p. 305. ISBN 0714121290.

- "Queensland Museum HMS Pandora". Archived from the original on 24 October 2017. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- "No. 12156". The London Gazette. 23 January 1781. p. 2.

- "No. 12229". The London Gazette. 29 September 1781. p. 2.

- "No. 12290". The London Gazette. 23 April 1782. pp. 2–3.

- "No. 12306". The London Gazette. 18 June 1782. p. 5.

- "No. 12618". The London Gazette. 1 February 1785. p. 66.

- "No. 12476". The London Gazette. 16 September 1783. p. 3.

- HMS Pandora's Logbook (Adm. MS 180) entry for Wednesday 11 August 1790 in: Gesner, 2016:80

- Alexander, p. 9.

- Alexander, p. 8.

- Alexander, p. 10.

- Alexander, p. 11.

- Alexander, p. 12.

- Maxton, p. 3.

- See the journal of Renouard, Midshipman David Thomas: Voyage of the Pandora's tender (1791) reprinted in: Maxton, 2020:143-156

- Gesner, Peter (June 2016). "'For condign punishment': a punitive voyage of the south pacific in the eighteenth century (ch. 2 Pandora Project Stage 2: four more seasons of excavation at the Pandora historic shipwreck)". Memoirs of the Queensland Museum – Culture. 9: 39. Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- The eventual History of the Mutiny on HMS Bounty [1831

- The True story of the Mutiny on the Bounty by Rutter Owen reports that Hillbrandt was lost when he couldn't get out of the "Pandora's Box"; Stewart and Summer were killed by a falling gangway; Skinner still manacled drowned

- Sharp, Nonie (1992). Footprints Along the Cape York Sandbeaches. Aboriginal Studies Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-855-75230-9.

- "Historical Chronicle". Universal Magazine of Knowledge and Pleasure. 91: 395. July 1792. Archived from the original on 11 November 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017 – via Google Books.

- Stone, Peter (2006). Encyclopedia of Australian Shipwrecks And Other maritime Incidents. Yarram, Vic.: Oceans Enterprises. p. 701. ISBN 0958665753.

- Cropp, Ben (1980). "We discover H.M.S. Pandora". This rugged coast. Adelaide : Rigby. pp. 74–88.

- "History of Pandora Inn". Retrieved 30 June 2020.

References

Alexander, Caroline (2003) 'Wreck of the Pandora' New Yorker 4 August Vol.79(21), p.44

Alexander, Caroline (2004). The Bounty: The True Story of the Mutiny on the Bounty. London: Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-00-653246-0.

Campbell, Janet; Gesner, Peter (2000). "Illustrated catalogue of artefacts from the HMS 'Pandora' wrecksite excavations 1977-1995". Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, Culture Volume 2 part 1: 53–159. ISSN 1440-4788

Conway, Christiane (2005). Letters from the Isle of Man — The Bounty-Correspondence of Nessy and Peter Heywood. Onchan, Isle of Man: The Manx Experience . ISBN 978-1-873120-77-4.

Hamilton, George (1793). A Voyage Round the World in His Majesty's Frigate Pandora. London: Berwick. p. 164.

Gesner, Peter (2000). HMS Pandora, an archaeological perspective (2nd revised ed.). Brisbane: Queensland Museum. ISBN 978-0-7242-4482-9.

Gesner, Peter (2016). "Pandora Project Stage 2: 4 more seasons of excavation at the Pandora historic shipwreck". Memoirs of the Queensland Museum – Culture. 9.

Henderson, Graeme (2016) 'The loss of HMS Pandora in 1791' (Chapter 5) pp 67–80 in: Swallowed by the Sea: the story of Australia's shipwrecks Canberra: National Library of Australia, 2016. ISBN 9780642278944

Marden, Luis (October 1985). "Wreck of H.M.S. [Pandora]: Tragic Sequel to [Bounty]". National Geographic. Vol. 168 no. 4. pp. 423–451. ISSN 0027-9358. OCLC 643483454.

Maxton, Donald A. (Ed.) (2020) Chasing the Bounty — The Voyages of the Pandora and Matavy. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc . ISBN 978-1-4766-7938-9.

Rawson, Geoffrey (1963) Pandora's last voyage. London: Longmans, c1963

Steptoe, Dayman (1998)The human skeletal material from HMS Pandora. Thesis, University of Queensland, 1998.

External links

- 'Pandora's Bounty' Wreck Detectives, BBC

- In Pursuit of the Bounty [videorecording]. [United States] : New Dominion Pictures in association with the Archaeological Institute of America, c1995.

- Maritime Archaeology - HMS Pandora

- Find Out about .. HMS Pandora. Queensland Museum.

- 'Dead Man Secrets'[blog re genealogical research to find DNA matches to identify human skeletal remains found in the wreck]

- Audio recording of ship surgeon George Hamilton's eyewitness account Voyage Round the World in His Majesty's Frigate Pandora at librivox

- Queensland Museum. Expedition leader's Chronicle [daily journal entries by expedition leader and team members during field work 1997, 1998 and 1999, archived at the National Library of Australia's web archive, PANDORA]

- Museum of Tropical Queensland. HMS Pandora

- Maritime archaeologist Peter Gesner leads Pandora warship research [conversation with Richard Fidler, ABC Radio National, 20 November 2013]

- DNA recovered from shipwrecked bones ABC News 27 November 1998

- Pandora's Secrets [Season 1 Episode 3, Journeys to the Bottom of the Sea Series BBC, 2000]

- Who was Harry? Q150 Digital Story [re one of the skeletons found on the wreck of HMS Pandora] State Library of Queensland

- HMS Pandora : in the wake of the Bounty [documentary film] Balgowlah, N.S.W. : David Flatman Productions, 1993.

- Marden, Luis. "Wreck of H. M. S [Pandora]: Tragic Sequel to [Bounty] Mutiny." National Geographic Magazine, Oct. 1985, p. 423+.