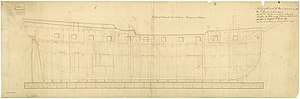

HMS Porcupine (1777)

HMS Porcupine was a 24-gun Porcupine-class sixth-rate post ship of the Royal Navy built in 1777 and broken up in 1805. During her career she saw service in the American War of Independence and the French Revolutionary Wars.

Porcupine | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | HMS Porcupine |

| Ordered: | 21 June 1776 |

| Awarded: | 25 June 1776 |

| Builder: | Edward Greaves, Limehouse |

| Laid down: | July 1776 |

| Launched: | 17 December 1777 |

| Completed: | 14 February 1778 |

| Commissioned: | December 1777 |

| Fate: | Broken up at Woolwich in April 1805 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | 24-gun Porcupine-class sixth-rate post ship |

| Tons burthen: | 519 59⁄94 (bm) |

| Length: |

|

| Beam: | 32 ft 2 1⁄2 in (9.817 m) |

| Draught: |

|

| Depth of hold: | 10 ft 3 in (3.12 m) |

| Sail plan: | Full-rigged ship |

| Complement: | 160 |

| Armament: |

|

Construction and commissioning

Porcupine cost £5,443.0.11d to build, plus £4,604.13.8d for fitting and coppering. She was commissioned under her first captain, William Finch, in December 1777.

Service

War with France

On 29 September 1778, Porcupine, Captain William Clement Finch, captured the French East Indiaman Modeste in the Bay of Biscay. Modeste, of 1000 tons, 26 guns and 95 men, was returning from China and richly laden. Her cargo was valued at £300,000, half of which was insured with English underwriters. Modeste became the East Indiaman Locko, which later made three voyages for the British East India Company.

On 15 March 1779, the British warships Apollo, Porcupine, and Milford captured the French privateer cutter Tapageur.[1] The Royal Navy took her into service under her existing name.

She came under the command of Captain Sir Charles Knowles around February 1780 and fought an action against two 36-gun xebecs off Valencia on 22 July 1781.[2] On 30 July 1780 she and the xebec HMS Minorca engaged the French frigate Montréal, the former British frigate HMS Montreal, off the Barbary coast. The two-hour engagement was indecisive and the British broke off the engagement.[2] [3]

Porcupine was stationed at Gibraltar during the Great Siege. In June 1782 the garrison there launched 12 gunboats. Each was armed with an 18-pounder gun and received a crew of 21 men drawn from Royal Navy vessels stationed at Gibraltar. Porcupine provided crews for five: Europa, Fury, Scourge, Terrible, and Terror.[4]

On 13 and 14 September and 11 October, the garrison destroyed a number of floating batteries. In December 1784 there was a distribution of £30,000 in bounty money for the batteries and the proceeds of the sale of ships stores, including those of San Miguel.[5] A second payment of £16,000 followed in November 1785.[6] A third payment, this of £8,000 pounds, followed in August 1786.[7] June 1788 saw the payment of a fourth tranche, this of £4,000.[8] Porcupine's officers and crew shared in all four.

Between the wars

Porcupine was paid off in 1783. Between August 1784 and June 1786 she underwent repairs and fitting. She was recommissioned for service off Scotland. She then underwent fitting for Channel service, but then was off Scotland again.[9]

In 1788, Porcupine took part in commemorations marking the hundredth anniversary of the siege of Derry.[10]

Porcupine was at Plymouth between November 1791 and January 1792. Captain Edward Buller recommissioned her in August. Captain Manley Dixon replaced Buller in 1793.[9]

French Revolutionary Wars

Porcupine was one of 46 ships at Plymouth that benefited from the seizure of several Dutch merchantmen and East Indiamenn on 30 January 1795.[11] The next day a squadron under Captain Sir John Borlase Warren detained the Dutch East India Ship Ostenhuyson, and Porcupine benefited from that too.[12]

In August Captain John Draper replaced Dixon.[9] On 26 September Porcupine and Minotaur recaptured the Walsingham Packet. The French corvette brig Insolent, of 18 guns and 90 men, had captured Walsingham Packet on 13 September as Walsingham Packet was sailing from Falmouth to Lisbon. Insolent narrowly escaped being herself captured at the recapture of Walsingham Packet, getting into Lorient as the British ships came into range.[13][Note 1]

On 20 March 1796 Porcupine captured the French privateer Coureur. Porcupine was about three or four leagues SSW of The Lizard when the revenue cutter Fox informed Porcupine that a French privateer had just captured an English brig. Porcupine set out in chase and quickly recaptured Diamon, of Aberdeen, George Killer, master. Draper sent a prize crew aboard with orders to take Diamon into the nearest port, and then set out after the privateer. The privateer put on such a press of sail that she lost her maintopmast, which enabled Porcupine to come up. Coureur, of 144 tons (bm), was pierced for 14 guns but only carried eight. She and her crew of 80 men had left Saint-Malo the day before. In addition to the brig Coureur had captured, Coureur was in chase of another merchant ship as Porcupine came on the scene, and there were other merchant vessels in sight as well that the privateer might have taken.[15][Note 2]

Between November to December 1796 Porcupine captured the Spanish vessels La Merced, St Ignacio, Nostra Senora de la Rigla, Monserrat, Trinidad, and Santa Eulatia.[17]

In July 1797 Captain Charles Pater replaced Draper. Pater sailed her to Halifax, Nova Scotia, the next month.[9]

Captain Andrew Evans assumed command in October 1798.[9] Porcupine and St Albans shared in the capture on 8 November of the brig Molly.[18]

Porcupine returned from Halifax on 15 December 1800 having escorted the merchant ships America and Diamond. Porcupine was carrying Commissioner Duncan, whom she landed at Plymouth.[19]

On 6 April 1801 Porcupine left Portsmouth as one of the escorts for a convoy to the West Indies.[20] She returned on 22 September 1802; she was paid off on 13 October at Plymouth and laid up in ordinary.[21]

Fate

Porcupine was broken up at Woolwich in April 1805.[9]

External links

Notes, citations, and references

Notes

- Insolente may be a vessel of Bordeaux "often be described as a brig, but listed as a corvette". She had a crew of 120 men and was armed with fourteen to eighteen 6-pounder guns. The British captured her at Port-Navalo.[14]

- Coureur was 85-tonne privateer commissioned in Saint-Malo in 1795 under François Galais with 67 to 80 men and 10 guns.[16]

Citations

- "No. 12016". The London Gazette. 21 September 1779. p. 4.

- Winfield (2007), p. 190.

- Henry G. Bohn, "Battles of the British Navy", Joseph Allen, ESQ. R.N., Volume 1, 1853, pp.307

- Drinkwater (1905), p. 246.

- "No. 12596". The London Gazette. 16 November 1784. p. 3.

- "No. 12699". The London Gazette. 12 November 1785. p. 523.

- "No. 12774". The London Gazette. 1 August 1786. p. 347.

- "No. 12997". The London Gazette. 7 June 1788. p. 278.

- Winfield (2008), p. 228.

- Gebler (2005), p. 324.

- "No. 15407". The London Gazette. 15 September 1801. p. 1145.

- "No. 15248". The London Gazette. 15 April 1800. p. 367.

- "No. 13818". The London Gazette. 29 September 1795. p. 1022.

- Demerliac (2004), p. 81, n°468.

- "No. 13878". The London Gazette. 26 March 1796. p. 291.

- Demerliac (2004), p. 243, n°2055.

- "No. 14006". The London Gazette. 2 May 1797. p. 402.

- "No. 15523". The London Gazette. 12 October 1802. p. 1097.

- Naval Chronicle, Vol. 4, p.524.

- Naval Chronicle, Vol. 5, p.373.

- Naval Chronicle, Vol. 8, p.347.

References

- Demerliac, Alain (2004). La Marine de la Révolution: Nomenclature des Navires Français de 1792 A 1799 (in French). Éditions Ancre. ISBN 2-906381-24-1.

- Drinkwater, John (1905) A History of the Siege of Gibraltar, 1779-1783: With a Description and Account of that Garrison from the Earliest Times. (J. Murray).

- Gebler, Carlo (2005) The siege of Derry, a history Little, Brown ISBN 978-0-316-86128-1.

- Winfield, Rif (2007). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1714-1792: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84415-700-6.

- Winfield, Rif (2008). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1793–1817: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-246-1.