HMS Duke of York (17)

HMS Duke of York was a King George V-class battleship of the Royal Navy. Laid down in May 1937, the ship was constructed by John Brown and Company at Clydebank, Scotland, and commissioned into the Royal Navy on 4 November 1941, subsequently seeing combat service during the Second World War.

HMS Duke of York in March 1942, while escorting Convoy PQ 12 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | HMS Duke of York |

| Namesake: | George VI (previously the Duke of York)[1] |

| Ordered: | 16 November 1936 |

| Builder: | John Brown and Company, Clydebank, Scotland |

| Yard number: | 554[2] |

| Laid down: | 5 May 1937 |

| Launched: | 28 February 1940 |

| Commissioned: | 4 November 1941 |

| Decommissioned: | November 1951 |

| Stricken: | 18 May 1957 |

| Identification: | Pennant number: 17 |

| Fate: | Scrapped in 1957 at Shipbreaking Industries, Ltd., Faslane, Scotland |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | King George V-class battleship |

| Displacement: | 42,076 long tons (42,751 t) deep load |

| Length: |

|

| Beam: | 103 ft 2 in (31.4 m) |

| Draught: | 34 ft 4 in (10.5 m) |

| Installed power: | 110,000 shp (82,000 kW) |

| Propulsion: | |

| Speed: | 28.3 knots (52.4 km/h; 32.6 mph) |

| Range: | 15,600 nmi (28,900 km; 18,000 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: | 1,556 (1945) |

| Sensors and processing systems: | |

| Armament: |

|

| Armour: | |

| Aircraft carried: | 4 × Supermarine Walrus seaplanes |

| Aviation facilities: | 1 × double-ended catapult (removed early 1944) |

In mid-December 1941, Duke of York transported Prime Minister Winston Churchill to the United States to meet President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Of the journey through seas rough even for the North Atlantic, Churchill wrote to his wife “Being in a ship in such weather as this is like being in a prison, with the extra chance of being drowned.” Between March and September 1942 Duke of York was involved with convoy escort duties, including as flagship of the Heavy Covering Force of Convoy PQ-17, but in October she was dispatched to Gibraltar where she became the flagship of Force H.

In October 1942, Duke of York was involved in the Allied invasion of North Africa, but saw little action as her role only required her to protect the accompanying aircraft carriers. Duke of York stopped the Portuguese vessel Gil Eannes on 1 November 1942 and a commando arrested Gastão de Freitas Ferraz. The British had picked up radio traffic indicating naval espionage, possibly compromising the secrecy of the upcoming Operation Torch.

After Operation Torch, Duke of York was involved in Operations Camera and Governor, which were diversionary operations designed to draw the Germans' attention away from Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily. On 4 October, Duke of York operated with her sister ship Anson in covering a force of Allied cruisers and destroyers and the American carrier Ranger, during Operation Leader, which raided German shipping off Norway. The attack sank four merchant ships and badly damaged a further seven.

On 26 December 1943 Duke of York was part of a task force which encountered the German battleship Scharnhorst off the North Cape of Norway. During the engagement that followed, Scharnhorst hit Duke of York twice with little effect, but was herself hit by several of Duke of York's 14-inch shells, silencing one of her turrets and hitting a boiler room. After temporarily escaping from Duke of York's heavy fire, Scharnhorst was struck several times by torpedoes, allowing Duke of York to again open fire, contributing to the eventual sinking of Scharnhorst after a running action lasting ten-and-a-half hours.

In 1945, Duke of York was assigned to the British Pacific Fleet as its flagship, but suffered mechanical problems in Malta which prevented her arriving in time to see any action before Japan surrendered.

After the war, Duke of York remained active until she was laid up in November 1951. She was eventually scrapped in 1957.

Construction

In the aftermath of the First World War, the Washington Naval Treaty was drawn up in 1922 in an effort to stop an arms race developing between Britain, Japan, France, Italy and the United States. This treaty limited the number of ships each nation was allowed to build and capped the displacement of capital ships at 35,000 long tons (36,000 t).[5] These restrictions were extended in 1930 through the Treaty of London, but by the mid-1930s Japan and Italy had withdrawn from both of these treaties and the British became concerned about the lack of modern battleships in the Royal Navy. The Admiralty therefore ordered the construction of a new battleship class: the King George V class. Due to the provisions of both the Washington Naval Treaty and the Treaty of London, both of which were still in effect when the King George Vs were being designed, the main armament of the class was limited to the 14 in (356 mm) guns. They were the only battleships built at that time to adhere to the treaty and even though it soon became apparent to the British that the other signatories to the treaty were ignoring its requirements, it was too late to change the design of the class before they were laid down in 1937.[6]

Duke of York was the third ship in the King George V class, and was laid down at John Brown & Company's shipyard in Clydebank, Scotland, on 5 May 1937. The title of Duke of York was in abeyance at that time, having been that held by King George VI prior to his succession to the throne in December 1936. The battleship was launched on 28 February 1940 and completed on 4 November 1941, and joined the Home Fleet at Scapa Flow.[7]

Description

Duke of York displaced 36,727 long tons (37,300 t) as built and 42,076 long tons (42,800 t) fully loaded. The ship had an overall length of 700 feet (213.4 m), a beam of 103 feet (31.4 m) and a draught of 29 feet (8.8 m). Her designed metacentric height was 6 feet 1 inch (1.85 m) at normal load and 8 feet 1 inch (2.46 m) at deep load.[8][9][10]

She was powered by Parsons geared steam turbines, driving four propeller shafts. Steam was provided by eight Admiralty 3-drum water-tube boilers which normally delivered 100,000 shp (75,000 kW), but could deliver 110,000 shp (82,000 kW) at emergency overload.[N 1] This gave Duke of York a top speed of 28 knots (52 km/h; 32 mph).[6][13] The ship carried 3,700 long tons (3,800 t) of fuel oil, which was later increased to 4,030 long tons (4,100 t).[7] She also carried 183 long tons (200 t) of diesel oil, 256 long tons (300 t) of reserve feed water and 430 long tons (400 t) of freshwater.[14] At full speed Duke of York had a range of 3,100 nmi (5,700 km; 3,600 mi) at 27 knots (50 km/h; 31 mph).[15]

Armament

Duke of York mounted 10 BL 14 in (356 mm) Mk VII guns, which were mounted in one Mark II twin turret forward and two Mark III quadruple turrets, one forward and one aft. The guns could be elevated 40 degrees and depressed 3 degrees, while their training arcs varied. Turret "A" was able to traverse 286 degrees, while turrets "B" and "Y" could both move through 270 degrees. Hydraulic drives were used in the training and elevating process, achieving rates of two and eight degrees per second, respectively. A full gun broadside weighed 15,950 lb (7,230 kg), and a salvo could be fired every 40 seconds.[16] The secondary armament consisted of 16 QF 5.25 in (133 mm) Mk I dual purpose guns which were mounted in eight twin turrets.[17] The maximum range of the Mk I guns was 24,070 yd (22,009.6 m) at a 45-degree elevation, the anti-aircraft ceiling was 49,000 ft (14,935.2 m). The guns could be elevated to 70 degrees and depressed to 5 degrees.[18] The normal rate of fire was ten to twelve rounds per minute, but in practice the guns could only fire seven to eight rounds per minute.[17]

Along with her main and secondary batteries, Duke of York carried 48 QF 2 pdr (40 mm (1.6 in)) Mk.VIII "pom-pom" anti-aircraft guns in six octuple, power-driven, mountings. These were supplemented by six 20 mm (0.8 in) Oerlikon light AA guns in single, hand-worked, mounts.[19]

Operational history

Second World War

.jpg)

In mid-December 1941, Duke of York embarked Prime Minister Winston Churchill for a trip to the United States to confer with President Franklin D. Roosevelt. She arrived at Annapolis, Maryland, on 22 December 1941, made a shakedown cruise to Bermuda in January 1942, and departed for Scapa Flow on 17 January with Churchill returning home by air.[20][21]

On 1 March 1942, she provided close escort for Convoy PQ 12 in company with the battlecruiser Renown, the cruiser Kenya, and six destroyers. On 6 March, that force was reinforced with one of Duke of York's sister-ships, King George V, and the aircraft carrier Victorious, the heavy cruiser Berwick, and six destroyers as a result of Admiral John Tovey's concerns that the battleship German battleship Tirpitz might attempt to intercept the convoy. On 6 March, the German battleship put to sea and was sighted by a British submarine around 19:40; no contact was made, however, except for an unsuccessful aerial torpedo attack by aircraft from Victorious.[20]

Later that month, Convoy PQ 13 was constituted and Duke of York again formed part of the escort force.[22] In early April, Duke of York, King George V, and the carrier Victorious formed the core of a support force that patrolled between Iceland and Norway to cover several convoys to the Soviet Union.[23] In late April, when King George V accidentally rammed and sank the destroyer Punjabi in dense fog, sustaining significant bow damage, Duke of York was sent to relieve her.[24] She continued in these operations through May, when she was joined by the American battleship USS Washington.[25] In mid-September, Duke of York escorted Convoy QP 14.[26]

In October 1942, Duke of York was sent to Gibraltar as the new flagship of Force H, and supported the Allied landings in North Africa the following month.[27] During this time Duke of York came under air attack by Italian aircraft on several occasions, but the raids were relatively small scale and were swiftly dealt with by the "umbrella" provided by the aircraft from the accompanying carriers Victorious, Formidable and Furious. After this action, Duke of York returned to Britain for a refit.[28]

With her refit completed, Duke of York resumed her status as flagship from 14 May 1943 pending the departure of King George V and Howe for Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily. Operation Gearbox in June 1943 involved a sweep by Duke of York and Anson, in company with the US battleships USS Alabama and South Dakota, to provide distant cover for minor operations in Spitsbergen and the Kola Inlet, while the following month diversionary operations, code-named "Camera" and "Governor of Norway," were carried out in order to draw the Germans' attention away from Operation Husky.[28] On 4 October, Duke of York and Anson covered a force of Allied cruisers and destroyers and the American carrier USS Ranger under Operation Leader, which raided German shipping off Norway. The attack resulted in the sinking of four German merchant ships and damage to seven others, which forced many of them to be grounded.[29]

Action with Scharnhorst

In 1943, the German battleship Scharnhorst moved to Norway, a position whence she could threaten the Arctic convoys to Russia. With Tirpitz and two armoured ships also in Norwegian fjords, it was necessary for the Royal Navy to provide heavy escorts for convoys between Britain and Russia. One of these was sighted by the Germans in early December 1943, and Allied intelligence concluded that the following convoy, Convoy JW 55B, would be attacked by the German surface ships. Two surface forces (Forces 1 and 2) were assigned to provide distant cover to JW 55B, which had left Loch Ewe on 22 December. On 25 December 1943, Scharnhorst was reported at sea, escorted by five Narvik-class destroyers (Z-29, Z-30, Z-33, Z-34, and Z-38). Force 1, comprising the County-class heavy cruiser Norfolk, and the Town-class light cruisers Belfast and Sheffield, made contact shortly after 0900 on 26 December. A brief gunnery engagement followed, without damage to Force 1, but two hits from a cruiser's guns upon Scharnhorst resulted in the destruction of her radar controls. In worsening weather, unable to effectively control her fire, Scharnhorst was unable to convert a tactical advantage of greater range and weight of shot. Fearing she was in a gunnery duel with a battleship, Scharnhorst turned away, outdistancing her pursuers. She again outran Force 1 after a second brief skirmish around noon that did not further damage Scharnhorst, but did result in hits on Norfolk which disabled a main battery turret and her radar.[30] Kriegsmarine Konteradmiral (Rear Admiral) Erich Bey, aboard Scharnhorst, having already detached his destroyers to independently seek out Convoy JW 55B, ordered Scharnhorst to return to port at Altafjord, Norway.

Meanwhile, Force 2, comprising Duke of York, the Crown Colony-class light cruiser Jamaica, and four destroyers (the S-class Saumarez, Savage, and Scorpion, and the Norwegian destroyer Stord), was closing, and it was estimated that a night action with Scharnhorst would commence around 1715. But Scharnhorst altered course, and Belfast regained radar contact, passing it to Force 2. Duke of York made her initial radar contact at 1617, at a distance of 45,500 yd (41,600 m), and Force 2 began to manoeuvre for broadside fire and torpedo runs by the destroyers. Belfast fired star shells at 1648 to illuminate Scharnhorst, followed by another star shell from one of Duke of York's 5.25 in (133 mm) guns, taking Scharnhorst by surprise with her main battery trained fore and aft. By 1650, Duke of York had closed to less than 12,000 yd (11,000 m) and opened fire with a full 10-gun broadside, scoring one hit. Although under heavy fire, Scharnhorst's return fire straddled Duke of York a number of times and hit her twice. A 28.3 cm (11.1 in) shell passed through the mainmast and its port leg without detonating,[31] but fragments from the hit destroyed the cable for the main search radar. A 15-centimetre (5.9 in) shell also pierced the port strut of the foremast without exploding.[32] At 1655, a 14 in (356 mm) shell from Duke of York silenced Scharnhorst's forward main battery turrets Anton and Bruno, but she maintained speed so that by 1824 the range had opened to 21,400 yd (19,600 m), when Duke of York ceased fire after expending 52 broadsides.[33] However, one shell from the final salvoes pierced Scharnhorst's armour belt and destroyed her No. 1 boiler room, slowing the ship and allowing the pursuing British destroyers to overtake her.[34]

Force 2's destroyers attacked at 1850 with torpedoes, launching 28 and scoring hits with four. This further slowed Scharnhorst, and at 1901 Duke of York and Jamaica again opened fire, at a range of 10,400 yd (9,500 m). At 1915, Belfast also began shelling Scharnhorst, and both Belfast and Jamaica fired their remaining torpedoes. At least ten 14-inch shells had already hit the German battleship, causing fires and explosions, and silencing most of the secondary battery. By 1916, all three main 28.3-centimetre (11.1 in) turrets aboard Scharnhorst had ceased firing, and her speed had been cut to 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). Duke of York ceased fire at 1930 to allow her escorting cruisers and destroyers to close on Scharnhorst.[32] In the final stages of the battle, the destroyers Matchless, Musketeer, Opportune, and Virago fired a total of 19 torpedoes at Scharnhorst, causing her to list badly to port, and at 1945 Scharnhorst capsized and quickly sank after a running action lasting ten-and-a-half hours, taking with her 1,932 men (there were only 36 survivors).[35] Following her sinking, and the retreat of most of the remaining German heavy surface units from Norway, the need to maintain powerful surface forces in British home waters diminished.[20]

Subsequent operations

On 29 March 1944, Duke of York and the bulk of the Home Fleet left Scapa Flow to provide a support force for Convoy JW 58.[36] The ship operated in the Arctic and as cover for carriers conducting the Goodwood series of air strikes on Tirpitz in mid to late August.[37] In September, when she was overhauled and partially modernized at Liverpool, radar equipment and additional anti-aircraft guns were added. She was then ordered to join the British Pacific Fleet and sailed in company with her sister-ship Anson on 25 April 1945. A problem with the ship's electrical circuitry delayed her while she was at Malta and, as a result, she did not reach Sydney until 29 July, by which time it too late for her to take any meaningful part in hostilities against the Japanese.[7]

Nevertheless, in early August, Duke of York was assigned to Task Force 37, along with four aircraft carriers and her sister-ship King George V. From 9 August, TF 37 and three American carrier task forces conducted a series of air raids on Japan, which continued until 15 August when a surrender came into effect.[38] After the conclusion of hostilities, Duke of York, alongside her sister-ship, King George V, participated in the surrender ceremonies that took place in Tokyo Bay. The following month Duke of York sailed for Hong Kong, to join the fleet that assembled there to accept the surrender of the Japanese garrison.[7] She was the flagship of the British Pacific Fleet when the Japanese surrendered, and remained so until June 1946, when she returned to Plymouth for an overhaul.[39]

Post war

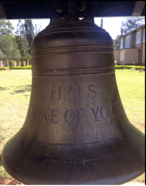

Duke of York was flagship of the Home Fleet following the end of the war and remained in active service until April 1949.[39] She was laid up in November 1951, and on 18 May 1957, she was ordered scrapped. She was broken up by Shipbreaking Industries, Ltd., in Faslane.[40] The ship's bell was salvaged and given to the Duke of York School (since renamed the Lenana School) in Nairobi, Kenya.

Refits

During her career, Duke of York was refitted on several occasions to bring her equipment up-to-date. The following are the dates and details of the refits undertaken.[41]

| Dates | Location | Description of Work |

|---|---|---|

| April 1942 | Rosyth | 8 × single 20mm added.[42] |

| December 1942 – March 1943 | Rosyth | 14 × single 20mm added.[43] |

| Early 1944 | 2× single 20mm removed; 2 × twin 20mm added.[43] | |

| September 1944 – April 1945 | Liverpool | 2× 4-barrelled 40mm added, 2× 8-barrelled 2-pdr pom-pom added, 6× 4-barrelled 2-pdr pom-pom added, 14× twin 20mm added, 18× single 20mm removed, Aircraft facilities removed.[42] Type 273 radar removed, Type 281 radar replaced by Type 281B radar, Type 284 radar replaced by 2× Type 274 radar; 2× Types 277, 282 and 293 radars added.[43] |

| 1946 | 4× 4-barrelled 2-pdr pom-pom added, 25 × single 20mm removed.[43] |

References

- Notes

- The King George V-class battleships had their steam plant specifications revised during the building phase, and as built the ships actually produced 110,000 shp (82,000 kW) at 230 rpm, and were designed for an overload power of 125,000 shp (93,000 kW), which was exceeded in service.[11][12]

Citations

- Naval History – HMS Duke of York (Accessed 13 August 2014)

- "HMS Duke of York". Clydebuilt Ships Database. Archived from the original on 16 April 2005. Retrieved 15 February 2010.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- Chesneau, pp. 54–55

- Konstam, p. 22

- Raven and Roberts, p. 107

- Konstam, p. 20

- Chesneau (Conways), p. 15

- Chesneau (2004), p. 15

- Garzke, p. 249

- Raven and Roberts, p. 284

- Raven and Roberts, p.284 and 304

- Garzke, p. 191

- Garzke, p. 238

- Garzke, p. 253

- Chesneau, p. 6

- Garzke, p. 227

- Garzke, p. 229

- Garzke, p. 228

- Raven and Roberts, pp. 287, 290

- Garzke, p. 216

- Burt, p. 418

- Rohwer, p. 153

- Rohwer, p. 158

- Rohwer, p. 162

- Rohwer, p. 167

- Rohwer, p. 195

- Konstam, p. 43

- Chesneau, p.14

- Rohwer, p. 280

- Garzke, p. 218

- Raven and Roberts, p. 356

- Garzke, p.220

- Garzke, p.219

- Operation "Ostfront" - The Battle off the North Cape (25-26. December 1943).

- Chesneau, pp. 14–15

- Rohwer, p. 314

- Rohwer, p. 350

- Rohwer, p. 426

- Garzke, p. 221

- Garzke, p. 222

- Chesneau, p. 52

- Konstam, p. 37

- Chesneau, p. 55

Bibliography

- Breyer, Siegfried (1973). Battleships and Battlecruisers 1905–1970. Garden City, New York: Doubleday and Company. OCLC 702840.

- Burt, R. A. (1993). British Battleships, 1919–1939. London: Arms and Armour Press. ISBN 1-85409-068-2.

- Chesneau, Roger, ed. (1980). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1922–1946. Greenwich: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-146-7.

- Chesneau, Roger (2004). King George V Battleships. ShipCraft. 2. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-211-9.

- Garzke, William H., Jr.; Dulin, Robert O., Jr. (1980). British, Soviet, French, and Dutch Battleships of World War II. London: Jane's. ISBN 978-0-71060-078-3.

- Konstam, Angus (2009). British Battleships 1939–45 (2) Nelson and King George V classes. New Vanguard. 160. Oxford, England: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84603-389-6.

- Raven, Alan; Roberts, John (1976). British Battleships of World War Two: The Development and Technical History of the Royal Navy's Battleship and Battlecruisers from 1911 to 1946. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-817-4.

- Rohwer, Jürgen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea, 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two. Annapolis, Maryland: US Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-119-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to HMS Duke of York (17). |