Gunnhild, Mother of Kings

Gunnhildr konungamóðir (mother of kings) or Gunnhildr Gormsdóttir,[1] whose name is often Anglicised as Gunnhild (c. 910 – c. 980) is a quasi-historical figure who appears in the Icelandic Sagas, according to which she was the wife of Eric Bloodaxe (king of Norway 930–34, 'King' of Orkney c. 937–54, and king of Jórvík 948–49 and 952–54). She appears prominently in sagas such as Fagrskinna, Egils saga, Njáls saga, and Heimskringla.

| Gunnhildr Gormsdóttir | |

|---|---|

| Queen-consort of Norway | |

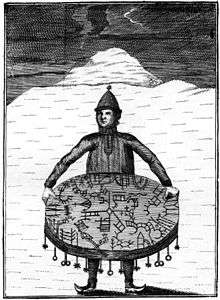

Gunnhild as an old woman. Illustration by Krohg. | |

| Consort | 931–934 (Norway) |

| Born | c. 910 Jutland, Denmark |

| Died | c. 980 (Aged ~70) Orkney, Scotland |

| Spouse | Eric Bloodaxe |

| Issue | Gamle Eirikssen Guttorm Eirikssen Harald II Ragnfrød Eirikssen Ragnhild Eriksdotter Erling Eirikssen Gudrød Eiriksson Sigurd Sleva Rögnvald Eriksson (?) |

| Dynasty | Fairhair (by marriage) Knýtlinga (by birth) |

| Father | Gorm the Old or Ozur Toti |

| Mother | unknown, possibly Thyra |

The sagas relate that Gunnhild lived during a time of great change and upheaval in Norway. Her father-in-law Harald Fairhair had recently united much of Norway under his rule. Shortly after his death, Gunnhild and her husband were overthrown and exiled. She spent much of the rest of her life in exile in Orkney, Jorvik and Denmark. A number of her many children with Erik became co-rulers of Norway in the late tenth century.

Historicity

Many of the details of her life are disputed, including her parentage. Although she is treated in the sagas as a historical person, even her historicity is a matter of some debate.[2] What details of her life are known come largely from Icelandic sources, which generally asserted that the Icelandic settlers had fled from Harald's tyranny. While the historicity of sources as the Landnámabók is disputed, the perception that Harald had exiled or driven out many of their ancestors led to an attitude among Icelanders generally hostile to Erik and Gunnhild. Scholars such as Gwyn Jones therefore regard some of the episodes reported in them as suspect.[3]

In the sagas, Gunnhild is most often depicted in a negative light, and depicted as a figure known for her "power and cruelty, admired for her beauty and generosity, and feared for her magic, cunning, sexual insatiability, and her goading", according to Jenny Jochens.[4]

Her parentage was altered from Danish royalty to a farmer in Hålogaland in northern Norway, this made her native to a land neighboring Finnmark, and her tutelage in the magic arts by Finnish wizards became more plausible. This contrivance, Jones has argued, was the Icelandic saga-maker's attempt to mitigate the "defeats and expulsions of his own heroic ancestors" by ascribing magical abilities to the queen.[lower-alpha 1][5]

Origins

According to the 12th century Historia Norwegiæ, Gunnhild was the daughter of Gorm the Old, king of Denmark, and Erik and Gunnhild met at a feast given by Gorm. Modern scholars have largely accepted this version as accurate.[5][6] In their view, her marriage with Erik was a dynastic union between two houses, that of the Norwegian Ynglings and that of the early Danish monarchy, in the process of unifying and consolidating their respective countries. Erik himself was the product of such a union between Harald and Ragnhild, a Danish princess from Jutland.[7] Gunnhild being the daughter of Gorm the old would explain why she would seek shelter in Denmark after the death of her husband.

Heimskringla and Egil's Saga, on the other hand, assert that Gunnhild was the daughter of Ozur Toti, a hersir from Halogaland.[8] Accounts of her early life vary between sources. Egil's Saga relates that "Eirik fought a great battle on the Northern Dvina in Bjarmaland, and was victorious as the poems about him record. On the same expedition he obtained Gunnhild, the daughter of Ozur Toti, and brought her home with him."[9]

Gwyn Jones regarded many of the traditions that grew up around Gunnhild in the Icelandic sources as fictional.[5] However, both Theodoricus monachus and the Ágrip af Nóregskonungasögum report that when Gunnhild was at the court of Harald Bluetooth after Erik's death, the Danish king offered marriage to her; if valid, these accounts call into question the identification of Gunnhild as Harald's sister, but their most recent editors follow Jones in viewing their accounts of Gunnhild's origins as unreliable.[10]

Heimskringla relates that Gunnhild lived for a time in a hut with two Finnish wizards and learned magic from them. The two wizards demanded sexual favors from her, so she induced Erik, who was returning from an expedition to Bjarmaland, to kill them. Erik then took her to her father's house and announced his intent to marry Gunnhild.[11] The older Fagrskinna, however, says simply that Erik met Gunnhild during an expedition to the Finnish north, where she was being "fostered and educated ... with Mǫttull, king of the Finns".[12] Gunnhild's Finnish sojourn is described by historian Marlene Ciklamini as a "fable" designed to set the stage for placing the blame for Erik's future misrule on his wife.[13]

Marriage with Erik

Erik's kinslaying and exile

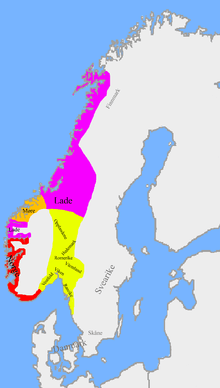

Red - the domain of the High King of Norway.

Yellow areas are petty kingdoms assigned to Harald's kinsmen.

Purple - the domain of the jarls of Hlaðir.

Orange - the domain of the jarls of Møre.

Gunnhild and Erik are said to have had the following children: Gamle, the oldest; then Guthorm, Harald, Ragnfrod, Ragnhild, Erling, Gudrod, and Sigurd Sleva.[14] Egil's Saga mentions a son named Rögnvald, but it is not known whether he can be identified with one of those mentioned in Heimskringla, or even whether he was Gunnhild's son or Erik's by another woman.

Gunnhild was widely reputed to have or otherwise employ magical powers.[15] Prior to the death of Harald Fairhair, Erik's popular half-brother Halfdan Haraldsson the Black died mysteriously, and Gunnhild was suspected of having "bribed a witch to give him a death-drink."[16] Shortly thereafter, Harald died and Erik consolidated his power over the whole country. He began to quarrel with his other brothers, egged on by Gunnhild, and had four of them killed, beginning with Bjørn Farmann and later Olaf and Sigrød in battle at Tønsberg.[17] As a result of Erik's tyrannical rule (which was likely greatly exaggerated in the sagas) he was expelled from Norway when the nobles of the country declared for his half-brother, Haakon the Good.[7]

Orkney and Jorvik

According to the Icelandic sagas, Erik set sail with his family and his retainers to Orkney, where they settled for a number of years. During that time Erik was acknowledged as "King of Orkney" by its de facto rulers, the jarls Arnkel and Erlend Turf-Einarsson.[18] Gunnhild went with Erik to Jorvik when, at the invitation of Bishop Wulfstan, the erstwhile Norwegian king settled as client king over northern England.[19] At Jorvik, both Erik and Gunnhild may have been baptized.[20]

Following Erik's loss of Jorvik and subsequent death at the Battle of Stainmore (954), the survivors of the battle brought word of the defeat to Gunnhild and her sons in Northumberland.[21] Taking with them all that they could, they set sail for Orkney, where they exacted tribute from the new jarl, Thorfinn Skullsplitter.[22]

Ultimately, however, Gunnhild decided to move on; marrying her daughter Ragnhild to Jarl Thorfinn's son Arnfinn, she took her other children and set sail for Denmark.[23]

It is worth noting that some modern historians call into question the identification of the Erik who ruled over Jorvik with Erik Bloodaxe. None of the English sources for Erik's reign in Northumbria identify him as Norwegian or as the son of Harald Fairhair. A thirteenth-century letter from Edward I to Pope Boniface VIII identifies Erik as Scottish in origin.[24] Lappenberg, Plummer and Todd, writing in the late nineteenth century, identified Erik as a son of Harald Bluetooth, a claim Downham discounts as untenable.[24] Downham, however, regards Erik the king of Jorvik as a distinct individual from Erik Bloodaxe, and thus views Gunnhild's sojourn in Orkney and Jorvik as the construct of later saga-writers who conflated different characters between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries.[25]

Conflict with Egill Skallagrímsson

Gunnhild was the nemesis of Egill Skallagrímsson, and his saga and poetry present her in a particularly negative light. Egil was introduced to Erik by his older brother Thorolf, who was a friend of the prince, and the brothers were originally on good terms with Erik and Gunnhild.[26] However, during a sojourn in Norway around 930, Egil got into an inheritance dispute with certain members of Erik's court, during which he killed Bárðr of Atley, one of the king's retainers.[27]

Gunnhild ordered her two brothers to kill Egil and Thorolf. Egil killed the pair when they confronted him, greatly increasing the Queen's thirst for revenge.[28]

Erik then declared Egil an outlaw in Norway. Berg-Önundr gathered a company of men to capture Egil, but was killed in his attempt to do so.[28] During his escape from Norway, Egil killed Rögnvald Eriksson, Erik's son.[29] He then cursed Erik and Gunnhild by setting a horse's head on a pole in a shamanic ritual (the pillar was a níðstöng or "níð-pole"; níð translates, roughly, to 'scorn' or 'curse'.) and saying:

"Here I set up a níð-pole, and declare this níð against King Erik and Queen Gunnhildr", — he turned the horse-head to face the mainland — "I declare this níð at the land-spirits there, and the land itself, so that all will fare astray, not to hold nor find their places, not until they wreak King Erik and Gunnhild from the land." He set up the pole of níð in the cliff-face and left it standing; he faced the horse's eyes on the land, and he rist runes upon the pole, and said all the formal words of the curse.[30]

The last encounter between Egil and Gunnhild occurred around 948 in Jorvik. Egil was shipwrecked on a nearby shore and came before Erik, who sentenced him to death. But Egil composed a drápa called "Höfuðlausn" in Erik's praise over a single night.[31] When he recited it in the morning, Erik gave him his freedom and forgave the killing of Rögnvald, against Gunnhild's wishes.[32]

Life after Erik

In Denmark

After the death of her husband, Gunnhild took refuge with her sons at the court of Harald Bluetooth at Roskilde.[33] Tradition ascribes to Gunnhild the commissioning of the skaldic poem Eiríksmál in honor of her fallen husband.[34]

In Denmark, Gunnhild's son Harald was fostered by the king himself, and her other sons were given properties and titles.[35] As King Harald was involved in a war against Haakon's Norway, he may have sought to use Gunnhild's sons as his proxies against the Norwegian king.[36] One of her sons, Gamle, died fighting King Haakon around 960.[37]

Return to Norway

Gunnhild returned to Norway in triumph when her remaining sons killed King Haakon at the Battle of Fitjar in 961. Ironically, the battle was a victory for Haakon's forces but his death left a power vacuum which Gunnhild's son Harald, with Danish aid, was able to exploit.[38] With her sons now ensconced as the lords of Norway, Gunnhild was from this time known as konungamóðir, or "Mother of Kings."[39]

During the reign of Harald Greyhide, Gunnhild dominated the court; according to Heimskringla she "mixed herself much in the affairs of the country."[40] Gunnhild's sons killed or deposed many of the jarls and petty kings that had hitherto ruled the Norwegian provinces, seizing their lands. Famine, possibly caused or exacerbated by these campaigns, plagued the reign of Harald.[41]

Among the kings slain (around 963) was Tryggve Olafsson whose widow Astrid Eriksdotter fled with her son Olaf Tryggvason to Sweden and then set out for the eastern Baltic.[42] According to Heimskringla Astrid's flight and its disastrous consequences were in response to Gunnhild having sent soldiers to kidnap or kill her infant son.[43]

Gunnhild was the patron and lover of Hrut Herjolfsson (or Hrútur Herjólfsson), an Icelandic chieftain who visited Norway during the reign of Gunnhild's son Harald.[44] This dalliance was all the more scandalous given the difference in their ages; the fact that Gunnhild was a generation older than Hrut was considered noteworthy.[45] Gunnhild engaged in public displays of affection with Hrut that were normally reserved for married couples, such as putting her arms around his neck in an embrace.[46] Moreover, Gunnhild had Hrut sleep with her alone in "the upper chamber."[47] Laxdaela Saga in particular describes the extent to which she became enamored of Hrut:

Gunnhild, the Queen, loved him so much that she held there was not his equal within the guard, either in talking or in anything else. Even when men were compared, and noblemen therein were pointed to, all men easily saw that Gunnhild thought that at the bottom there must be sheer thoughtlessness, or else envy, if any man was said to be Hrut's equal.[48]

She helped Hrut take possession of an inheritance by arranging the death of a man named Soti at the hands of her servant, Augmund and her son Gudrod.[49] When Hrut returned home, Gunnhild gave him many presents, but she cursed Hrut with priapism to ruin his marriage to Unn, daughter of Mord Fiddle; the two ultimately divorced.[50]

Gunnhild also showed great favor to Olaf the Peacock, Hrut's nephew, who visited the Norwegian court after Hrut's return to Norway. She advised him on the best places and items to trade and even sponsored his trade expeditions.[51]

Exile and death

Haakon Sigurdsson, jarl of Hlaðir, arranged the death of Harald Greyhide around 971 with the connivance of Harald Bluetooth, who had invited his foster-son to Denmark to be invested with new Danish fiefs. Civil war broke out between Jarl Haakon and the surviving sons of Erik and Gunnhild, but Haakon proved victorious and Gunnhild had to flee Norway once again, with her remaining sons Gudrod and Ragnfred.[52] They went to Orkney, again imposing themselves as overlords over Jarl Thorfinn.[53] However, it appears that Gunnhild was less interested in ruling the country than in having a place to live quietly, and her sons used the islands as a base for abortive raids on Haakon's interests; the government of Orkney was therefore firmly in the hands of Thorfinn.[54]

According to the Jómsvíkinga saga, Gunnhild returned to Denmark around 977 but was killed at the orders of King Harald by being drowned in a bog. The Ágrip and Theodoricus Monachus's Historia de Antiquitate Regum Norwagiensium contain versions of this account.[55]

In 1835, the body of a murdered or ritually sacrificed woman, the so-called Haraldskær Woman, was unearthed in a bog in Jutland. Because of the account of Gunnhild's murder contained in the Jomsviking Saga and other sources, the body was mistakenly identified as that of Gunnhild. Based upon the belief of her royal personage, King Frederick VI commanded an elaborate sarcophagus be carved to hold her body. This royal treatment of Haraldskær Woman’s remains explains the excellent state of conservation of the corpse; conversely, Tollund Man, a later discovery, was not properly conserved and most of the body has been lost, leaving only the head as original material in his display. Later radiocarbon dating demonstrated that the Haraldskær Woman was not Gunnhild, but rather a woman who lived in the 6th century BCE.[56]

Reputation for Sorcery in the Sagas

Gunnhild is often connected with sorcery, as seen throughout the Icelandic sagas. This magical ability may be recognized in part due to Gunnhild's affiliation with the Finns, having supposedly lived in a hut with two Finnish wizards in Finnmark and learned magic from them, according to Snorri in Heimskringla. Also as seen in Heimskringla, Eirík first made the acquaintance of Gunnhild when he was younger and off on a raid in northern Norway. His men had stumbled upon the Finns' hut where she was staying, and described her as "a woman so beautiful that they had never seen the like of her." [57] As stated in Heimskringla, Gunnhild convinced them to hide in the Finns' hut, and then spread the contents of a linen sack both inside and outside of the hut. It is thought that this action was an indication of magic, which upon the Finns' return, caused them to fall asleep without being easily awoken. Gunnhild completed her magic by covering their heads with seal skins, and then directing Eirík's men to kill them, after which they returned to Eirík. Gunnhild's Finnish sojourn is described by historian Marlene Ciklamini as a "fable" designed to set the stage for placing the blame for Eirik's misrule on his wife.[58]

Other sources acting as examples of Gunnhild's sorcery include the story of King Hákon's death in Snorri's Heimskringla, as well as instances concerning Egil in Egil's Saga, and suspicion surrounding the death of Halfdan Haraldsson . Heimskringla describes Hákon's ascent to the Norwegian throne after hearing of the cruelties caused by Eirík's rule. Hákon found great support among the Norwegian people, and therefore forced Eirík and Gunnhild to flee to England. Naturally many battles for the throne ensued, which ultimately led to Gunnhild getting blamed for Hákon's death, when an arrow flew towards him in battle piercing into the muscle of his upper arm. According to Heimskringla, it is stated that "through the sorcery of Gunnhildr a kitchen boy wheeled round, crying: 'Make room for the king's slayer!' and let fly the arrow into the group coming toward him and wounding the king." [59] Marlene Ciklamini reasons that the unusualness of the mortal wound directs the origin to possible sorcery involved, presumably by Gunnhild.[58]

The character of Egil in Egil's Saga is also cursed by being on Gunnhild's bad side after his many transgressions towards the Norwegian court. First attracting her attention and dislike at a feast when he became overly drunk and foolishly killed one of her supporters and after which escaped, Gunnhild placed a curse on Egil, "from ever finding peace in Iceland until she had seen him." [60] This curse of Gunnhild's is presumably the cause for Egil's later desire to travel to England, which was where Gunnhild and Eirík were at the time after being exiled. Egil ended up requesting to receive forgiveness from Eirík and Gunnhild, and was allowed a single night to compose a tributary poem to Eirík, or else face death. Gunnhild's second moment of sorcery in the saga appears later that night, when Egil was apparently distracted from his writing by a bird twittering at the window. This bird is reputed to be Gunnhild, who had shape-shifted into that form, as seen by Egil's companion Arinbjorn, who had "sat down near the attic window where the bird had been sitting, and saw a shape-shifter in the form of a bird leaving the other side of the house." [61]

Legacy and reputation

Carolyne Larrington takes an interesting look into the comparative amount of power Gunnhild held, as well as her overall role as queen within the Norwegian court. Queenship as a concept emerged relatively late in Norway, and as Larrington points out, the most powerful women in Norwegian history were usually king's mothers rather than kings' wives. Gunnhild acts as one of the most important partial exceptions to this rule, as she was influential during both Eirík's and her sons' rules. Gunnhild became increasingly politically active in her own right after her husband, Eirík, died in battle, after which she later returned to Norway where she put her sons in power, and her son Harald on the throne. Gunnhild also arranged her daughter's marriage to the strategically important Earl of Orkney, displaying her awareness for political advantage. Gunnhild remained resilient to maintain power for the rest of her life, acting as Queen Regent to her son Harald, and continuing to be a major deciding factor and source for political advice.[62]

Appearances in Media

Literature

Gunnhild was a villain in Robert Leighton's 1934 novel Olaf the Glorious,[63] a fictionalized biography of Olaf Tryggvason. She is the central character of the novel Mother of Kings by Poul Anderson,[64] (which makes her a granddaughter of Rognvald Eysteinsson, accepts the version of her living with the Finnish warlocks and emphasizes her being a witch) and also appears in Cecelia Holland's The Soul Thief.[65] In The Demon of Scattery[66] by Poul Anderson and Mildred Downey Broxon, and illustrated by Michael Whelan and Alicia Austin, the main characters, the Viking Halldor and the Irish ex-nun Brigit, become Gunnhild's paternal grandparents. She is a central character in Robert Low's "Crowbone".

Television

She is played by Icelandic actress Ragnheiður Ragnarsdóttir in the television series Vikings.[67]

Explanatory notes

- Jones subscribes to the theory that Snorri Sturlusan was the author of Egils saga and Heimskringla.

References

- Citations

- Or, alternatively, Gunnhildr Özurardóttir.

- Downham 112-120; Jones & (1968) 121–24; Bradbury 38; Orfield 129; Ashley 444; Alen 88; Driscoll 88, note 15.

- Jones & (1968) 121–24.

- Jochens, Jenny. Old Norse Images of Women. p. 180.

- Jones & (1968) 121–22.

- Bradbury 38; Orfield 129; Ashley 444; Alen 88; Driscoll 88, note 15.

- Jones & (1968) 94–95.

- For example, Harald Fairhair's Saga § 34. The Ágrip af Nóregskonungasögum calls her father Ozurr lafskegg [dangling beard], thus also Fagrskinna; Driscoll § 5 & p. 88, note 15.

- Egil's Saga § 37.

- Theodoricus, § 6 & p. 64, note 54; Driscoll, § 11 & p. 91, note 39.

- Harald Fairhair's Saga § 34.

- Fagrskinna § 8.

- Ciklamini 210-211.

- Harald Fairhair's Saga § 46.

- E.g., Harald Fairhair's Saga § 34; Njal's Saga §§ 5–8; Fox 289–310.

- "Harald Fairhair's Saga" § 44.

- Harald Fairhair's Saga §§ 45–46.

- E.g., Ashley 443–44.

- According to the "Saga of Haakon the Good", it was King Athelstan of England who appointed Erik as ruler of Jorvik, but this is chronologically problematic; Athelstan died in 939. Ashley, among others, proposes that Erik received his commission from Athelstan but did not take it up until later. Ashley 443–44.

- Saussaye 183.

- Haakon the Good's Saga §§ 4–5.

- Haakon the Good's Saga § 5.

- Ashley 443; see also Haakon the Good's Saga § 5; Fagrskinna §§ 8–9. Ragnhild would later, according to the Orkneyinga Saga, murder Arnfinn, marry his brother Havard, murder him in turn, and then marry their brother Ljot. Ashley 443–44.

- Downham 116.

- Downham 118.

- Egil's Saga § 36.

- Egil's Saga §§ 56–58.

- Egil's Saga §§ 59–60.

- Egil's Saga § 60.

- Egil's Saga § 60. the Icelandic source is, essentially, giving Egil credit for the ouster of Gunnhild and Erik from Norway.

- He did so despite being pestered by the noise of a bird, which he believed was Gunnhild disguised with magic. Egil's Saga § 62

- Egil's Saga § 64.

- Haakon the Good's Saga § 10. As noted above, Harald may have been Gunnhild's brother or half-brother.

- Jones & (1968) 123; Fagrskinna § 8; Haakon the Good's Saga § 10.

- Fagrskinna § 9; Haakon the Good's Saga § 10.

- Haakon the Good's Saga § 10.

- Haakon the Good's Saga § 26.

- Jones & (1968) 122. A story recorded in the Saga of Haakon the Good, regarded by Ciklamini as a fable, relates that Gunnhild brought about King Haakon's death through the use of a magic arrow shot by one of her servants. Ciklamini 211.

- Jones & (1968) 123–24.

- Jones & (1968) 123–25; Harald Grafeld's Saga § 1.

- Jones & (1968) 123–25; Harald Grafeld's Saga §§ 2–17.

- Jones & (1968) 124–25; Olaf Tryggvason's Saga §§ 2–3.

- Jones & (1968) 131–32; Olaf Tryggvason's Saga § 3.

- Ordower 41–61; Njal's Saga § 3.

- Jochens 204 at n. 56.

- Jochens 71.

- Jochens 73.

- Laxdaela Saga § 19.

- Njal's Saga § 5.

- Njal's Saga §§ 5–8; Fox 289–310. In describing the problem to her father, Unn says "when he comes to me his penis is so large that he can't have any satisfaction from me, and we've both tried every possible way to enjoy each other, but nothing works." Njal's Saga § 7. Earlier, more prudish translations such as Sir George W. DaSent's 1861 edition merely reported cryptically that Hrut and Unn "did not pull together well as man and wife" and that Hrut "was not master of himself."

- Laxdaela Saga § 21.

- Olaf Tryggvason's Saga §§ 16–18.

- Ashley 443; Olaf Tryggvason's Saga §§ 16–18.

- Ashley 443.

- See, generally, Ashley 443; Jomsvikinga Saga §§ 4–8.

- "Haraldskaer Woman: Bodies of the Bogs", Archaeology, Archaeological Institute of America, 10 December 1997. Radiochemical dating methods were not available until well into the twentieth century.

- Sturluson, Snorri. Heimskringla. p. 86.

- Ciklamini, Marlene. The Folktale in Heimskringla (Hálfdanar Saga Svarta. Hákonar Saga Góða).

- Sturluson, Snorri. Heimskringla. p. 123.

- Egil's Saga. p. 122.

- Egil's Saga. p. 126.

- Larrington, Carolyne. "Queens and Bodies: The Norwegian Translated lais and Hakon IV's Kinswomen". The Journal of English and Germanic Philology.

- Macmillan, 1929.

- Tor Books, 2003

- Forge Books, 2002.

- Ace Books, 1979.

- "From the Olympics to "Vikings" with New York Film Academy Acting Alum Ragga Ragnars". New York Film Academy. January 5, 2018. Retrieved December 27, 2018.

- Bibliography

- Alen, Rupert; Dahlquist, Anna Marie (1997). Royal Families of Medieval Scandinavia, Flanders, and Kiev. Kingsburg: Kings River Publications. ISBN 0-9641261-2-5.

- Ashley, Michael (1998). The Mammoth Book of British Kings and Queens. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 0-7867-0692-9.

- Bradbury, Jim (2007). The Routledge Companion to Medieval Warfare. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-41395-4.

- Chantepie de la Saussaye, Pierre Daniël (1902). The Religion of the Teutons. Handbooks on the History of Religions. Translated by Bert John Vos. Boston and London: Ginn & Co. OCLC 895336.

- Ciklamini, Marlene (1979). "The Folktale in Heimskringla (Hálfdanar saga svarta – Hákonar saga góða". Folklore. 90 (2): 204–216.

- Driscoll, Matthew J. (1995). Ágrip af Nóregskonungasǫgum a Twelfth-Century Synoptic History of the Kings of Norway. London: Viking Society for Northern Research. ISBN 0-903521-27-X.

- Finlay, Alison (2003). Fargrskinna, a Catalogue of the Kings of Norway: a Translation with Introduction and Notes. Boston: Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-04-13172-8.

- Forte, Angelo; Oram, Richard; Pedersen, Frederik (2005). Viking Empires. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82992-2.

- Downham, Clare (2007). Viking Kings of Britain and Ireland. Dunedin.

- Fox, Denton (Autumn 1963). "Njals Saga and the Western Literary Tradition". Comparative Literature. 15 (4): 289–310.

- Jochens, Jenny (1995). Women in Old Norse Society. Cornell University Press.

- Jones, Gwyn (1984) [1968]. A History of the Vikings. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-285139-X.

- Magnusson, Magnus; Hermann Pálsson (1960). Njal's Saga. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-044103-4.

- Ordower, Henry. Exploring the Literary Function of Law and Litigation in 'Njal's Saga. Cardozo Studies in Law and Literature. 3. pp. 41–61.

- Orfield, Lester B. (2002). The Growth of Scandinavian Law. Union: Lawbook Exchange Ltd. ISBN 978-1-58477-180-7.

- Kellogg, Robert; Smiley, Jane (2001). "Laxdaela Saga". The Sagas of Icelanders. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-100003-1.

- Sturluson, Snorri (1964). Heimskringla: History of the Kings of Norway. Lee M. Hollander (trans.). Austin: Published for the American-Scandinavian Foundation by the University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-73061-6.

- Theodoricus monachus; Foote, Peter (1998). Historia De Antiquitate Regum Norwagiensuim. London: Viking Society for Northern Research, University College London. ISBN 0-903521-40-7.

- Thorsson, Örnólfur (2000). "Egil's Saga". The Sagas of Icelanders: a Selection. New York: Viking Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0-9654777-0-3.

- Tunstall, Peter, trans. (2004). "The Tale of Ragnar's Sons (Translation)". Northvegr. Archived from the original on July 5, 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

- Jochens, Jenny (1928). Old Norse Images of Women. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

- Larrington, Carolyne (2009). Queens and Bodies: The Norwegian Translated lais and Hákon IV's Kinswomen, The Journal of English and Germanic Philology, Vol. 108, No. 4, pp. 506-527. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

External links

- Bodies of the Bogs: Haraldskaer Woman, Archaeology, Archaeological Institute of America, 10 December 1997.

- Caveats on Gunnhild's parentage

- Egil's Saga online

- Genealogy of Gunnhild

- Heimskringla online

- Leighton's Olaf the Glorious on Project Gutenberg.

Gunnhild, Mother of Kings | ||

| Preceded by Gyda Eiriksdottir |

Queen Consort of Norway 931–934 |

Succeeded by Tyri of Denmark |