Guards Rifles Battalion

The Guards Rifles Battalion (German: Garde-Schützen-Bataillon; French: Bataillon des Tirailleurs de la Garde; nicknamed: Neuchâteller in High German; Neffschandeller in Berlin German dialect) was an infantry unit of the Prussian Army. Together with the Guards Ranger Battalion (German: Garde-Jäger-Bataillon) it formed the light infantry within the 3rd Guards Infantry Brigade in the 2nd Guards Division of the Guards Corps. The battalion consisted of four companies.

History

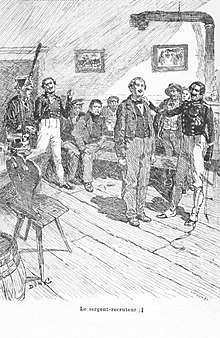

Since 1709 the Berlin-based Hohenzollern ruled the Principality of Neuchâtel in personal union with the Kingdom of Prussia.[1] They were deposed by Napoléon Bonaparte, and in 1806 he made the French Marshall Louis-Alexandre Berthier prince of Neuchâtel.[1] In the course of the Napoleonic Wars the principality provided for a rangers battalion as part of the Swiss Guards within Napoléon's Grande Armée since 1807. The rangers were nicknamed Canaris (i.e. canaries) because of their yellow uniforms. After in 1814 Neuchâtel was restituted to the Hohenzollern, Frederick William III of Prussia reassumed office as prince of Neuchâtel.[1] After the Liberation Wars the Conseil d’Etat (state council, i.e. government of Neuchâtel) addressed him in May 1814 requesting the permission to establish a special battalion, a Bataillon de Chasseurs, for the service of his majesty.[1]

Frederick William III then established by his most-supreme cabinet order (allerhöchste Cabinets-Ordre), issued in Paris on 19 May 1814, the Bataillon des Tirailleurs de la Garde following the same principals as with the Neuchâtel battalion within the Grande Armée.[1] To this end 400 men of 1.68 metres (5.5 ft) minimum height were to be recruited.[1] A number of demobilised Canaries and newly enlisted men were thus recruited.[1] Major Baron Charles-Gustave de Meuron (1779–1830)[2] became their first commander.[3]

On 5 January 1815 the battalion arrived in Berlin, having marched the way from Paris.[1] The guards rifles battalion was different from all other units serving the monarch since none of its soldiers were conscripts, but all volunteer Neuchâtelois, other Swiss, and Prussians.[4] The guards rifles, rather lacking men, were one of the units accepting one-year volunteers (Einjährig-Freiwillige).[5]

The battalion was to consist by two thirds of native Neuchâtelois and by one third of nationals of other Swiss cantons. However, this composition was indeed never realised. The required volunteer Neuchâtelois were usually hard to win so that many men of doubtful reputation and adventurers enlisted too.[4] So French, originally the vernacular and the command language, was soon replaced. Since 1816 all oral and written orders had to be in German only.[4] However, unlike other Prussian military units the guards rifles did not address their commander by his eventual military rank, but as "Herr Kommandant" (M. le commandant), which in the French Army is the rank equivalent to a Major, by this time the usual rank of a battalion commander.

The composition of the battalion and the behaviour of many a rifleman earned it an ambiguous reputation.[4] While women of Berlin considered the French-speaking riflemen as charming celibates and good dancers with an attracting Franco-German jargon, their less reputated comrades were also suspected of theft and worse crimes.[4] So the saying goes, that once at the royal table a guest reported that a corpse, dressed with nothing but a shirt, had been discovered in the Schlesischer Busch, a bush south of Köpenicker Straße in Berlin. The king then carefully asked the also present commander of the guards rifles: "It was not one of your men, commander, was it?" And the commander, possibly Major von Tilly, replied that this was not likely, since a guards rifleman would have taken the shirt too.[3][6]

When in 1848 Neuchâtel proclaimed to be a republic, thus abolishing monarchy, the recruitment in Switzerland ended.[3] After the Neuchâtel Crisis the Hohenzollern accepted their dethronement there in 1857 and left it up to the Swiss riflemen to quit the service.[3] However, many stayed, and one of the last Swiss serving was Captain Bernard de Gélieu (Neuchâtel, *28 September 1828 – 20 April 1907, Potsdam, as General of the Infantry).[7] He was a royalist Neuchâtelois, later distinguishing himself in the Neuchâtel Crisis,[8] but earlier proposed by the Conseil d'Etat of Neuchâtel in 1847, which had the right of nomination for the battalion's officers, only the commander to be chosen by the monarch.

Since 1841 the guards rifles were allowed to also recruit three-year volunteers (Dreijährig-Freiwillige), ordinary conscripts who did a volunteer third year of service after two years of regular duty, allowing them to choose the military units they want to join. After in 1845 all other rifles battalions had been renamed ranger battalions the guards rifles battalion was the only using this expression in the Prussian army. After 1848 all new recruits were Prussians, after 1871 also Alsace-Lorrainians were accepted.

Since the mid-19th century the battalion mostly recruited commoners and employees of forestry and proven hunters. After twelve years of service as ordinary soldier, or nine years as a noncommissioned officer, the respective rifleman received a guarantee writ (Forstversorgungsschein) to be afterwards employed in the Prussian state forestry. The higher officers were mostly of noble descent.

On 1 October 1902 the newly created guards machine gun detachment No. 2 (Garde-Maschinengewehr-Abteilung Nr. 2) was assigned to the guards rifles, but redeployed to the 4th Queen Augusta Guards Grenadiers in 1913, when a bicycle company and a new machine gun company became part of the battalion. Its reserve force were the guards reserve rifles battalion (Garde-Reserve-Schützen-Bataillon) and the 16th guards reserve ranger battalion (Reserve-Jäger-Bataillon Nr. 16).

In 1912, on the occasion of his state visit to Switzerland, German Emperor William II wore his uniform as the Prussian Royal Colonel of the guards rifles, which was received with lack of understanding by many Swiss. After the First World War the guards rifles battalion was disbanded.

After the November Revolution some demobilised riflemen joined the guards cavalry rifles division (Garde-Kavallerie-Schützen-Division), among them Robert Kempner.[9] In January 1919 the Freikorps Garde-Schützen was founded, which existed until early 1920 and operated in the Baltic states as well as in West Prussia.

Military operations

Operations until 1871

At the beginning of the Revolutions of 1848 in the German states the battalion, among other units, fought the riots in Berlin on 18 March 1848. While Karl August Varnhagen von Ense reported about fraternisations between riflemen and revolutionaries in his Journal der Märzrevolution, there is no other evidence for this. After that day the battalion was withdrawn from the city.

During the First Schleswig War 1848–1849 the battalion fought for the German Confederation near Schleswig (23 April), during the bombardment of Fredericia (8 May) and near Vester Sottrup/Horsens (5 June). In the course of the reactionary suppression of the revolution the battalion supported the gendarmerie arresting revolutionaries hiding in the Spreewald. Between 1856 and 1858 always one of the battalion's four companies was stationed on Hohenzollern Castle. Some of its officers, among them de Gélieu, were involved in the Neuchâtel Crisis in 1856.

In 1866 the battalion fought for Prussia during the Austro-Prussian War in the Battle of Königgrätz.[3] The 4th Company of the Guards Rifles, under Captain de Gélieu, conquered Austrian batteries near Lipa between Sadová and Königgrätz, as displayed by Christian Sell in a battle painting. During the Franco-Prussian War from 1870 to 1871 the battalion distinguished themselves in the Battles of Gravelotte,[3] Sedan, Le Bourget and during the Siege of Paris.

First World War

In the First World War the battalion was one of the first units advancing the western front. The battalion participated in the attack on Belgium and northern France. After fighting near the Aire on 13 September 1914 only 213 men, out of an original 1,250, remained fit for action, the others wounded or dead. The battalion was then replenished with reservists and volunteers. After operating in Champagne the battalion was fighting at the Hartmannswillerkopf in Alsace between April 1915 and November 1915. Then it was redeployed to the Serbian front in Macedonia, where it stayed until end of February 1918. In March 1918 the battalion returned to Alsace, not participating any more in major fights until the ceasefire.

The guards rifles were one of the ten front units marching through the Brandenburg Gate in December 1918, as stipulated between Friedrich Ebert, the head of the provisional German government, and the Oberste Heeresleitung, welcomed also by the government.

Guards reserve rifles battalion

The Guards reserve rifles battalion was first operating near Namur, but soon redeployed to East Prussia after the Russian invasion there (Battle of Tannenberg) and subsequently stationed in Upper Silesia. Between the end of May 1915 and early 1917 the reserve rifles were redeployed to the Russian Baltic governorates. As of July 1917 the reserve rifles operated in Galicia, only to advance the Italian front near Udine in October of that year. In April 1918 redeployed to the western front, the reserve rifles were employed at the Hermann Line and the Siegfried Line.

16th reserve ranger battalion

On 11 October 1914 the reserve rangers advanced the western front in Flanders. Many volunteers had joined this unit and little trained as they were the unit had lost already 145 casualties by the end 1914.

The commanders were changing quite often, indicating the lack of experienced men. All officers had been killed or wounded by the end of 1914 so that a Feldwebel (sergeant) was the remaining highest ranking man commanding. After redeployments to Galicia in 1915 and afterwards to the Serbian front, the reserve rangers returned to the western front fighting in the Battle of Verdun since May 1916. Between September 1916 and early 1917 the reserve rangers fought in Galicia, only to be redeployed again to Flanders, where they participated – among others – in the Battle of Passchendaele.

Until the ceasefire the reserve rangers remained in France. On 31 December 1918 they arrived in Lübben in order to be demobilised.

Garrisons

The battalion was originally stationed in infantry barracks (the Pfuel Barracks) on Köpenicker Straße 13–15 in the Luisenstadt quarter of Berlin.[1] The barracks building was destroyed in the bombing of Berlin in World War II. The real estate developer Johann Anton Wilhelm von Carstenn pushed the battalion's move to then Groß-Lichterfelde, a newly developed suburb of Berlin, also financing part of the necessary utilities.

Following a design of Construction Councillor Ferdinand Schönhals the government-employed architect Ernst August Roßteuscher laid out a comfortable new barracks compound in Lichterfelde West between 1881 and 1884.[10] On 27 September 1884 the battalion celebrated its farewell to the Pfuel Barracks in the Karlsgarten restaurant in the Hares' Heath.[11] Then the battalion moved into the new barracks on Gardeschützenweg.[11]

After the formation of the Reichswehr in 1919 the new 29th Reichswehr rifles battalion (Reichswehr-Schützen-Bataillon Nr. 29), part of the Infantry Regiment 9 Potsdam, moved into the barracks. After the Second World War the barracks happened to be in what had become the American sector of divided Berlin and thus the well preserved barracks, renamed Roosevelt Barracks, were taken over by the US Army in 1945. Between 1950 and 1958 the 6941st Guard Battalion was domiciled in the Roosevelt Barracks. After the redeployment of the US troops from Berlin in 1992 the Bundeswehr Berlin command (Standortkommando Berlin) intermittently used the barracks, now lodging departments of the Bundesnachrichtendienst.

Besides the Gardeschützenweg (literally guards riflemen way) in the area Fabeckstraße and Gélieustraße commemorate officers of the guards rifles, whereas Lipaer Straße and Neuchâteller Straße recall one of their battles and the original homeland of the riflemen.

Uniform

The first uniforms had been designed by a Parisian tailor[4] and consisted of a green coat and grey trousers, similar to that of the Silesian rifles, but distinguished from them by the black facing colour, red pipings at collar, cuffs and pane, and French-style cuffs.[12] The soldiers wore black felt shakos.

In 1843 the open coats were replaced by green closed ones. The shakos were replaced by Prussian Pickelhauben. On parades the riflemen wore white trousers. Since 1854 the guards rifles wore again shakos, but this time made from leather and showing the star of the Prussian royal guard and a cockade. Only slight variations appeared until 1918.

The trousers of the field uniform were first green.[13] During the First World War the battalion used field grey uniforms, the shakos were covered with grey textil coating.

The Prussian Schutzpolizei, newly formed after 1918, nicknamed the green police, received shakos like those of the guards rifles.[14] These kind of shakos remained in use by the police of the West German states until the 1960s. Also the green colour remained.

Maintenance of tradition

In the Reichswehr and the Wehrmacht the Infantry Regiment 9 carried on the tradition of the guards rifles. According to the tradition decree of the Bundeswehr first the 1st Panzergrenadier Battalion (reorganised as 521st ranger battalion as of 1980) in Northeim maintained the rifles' tradition. After the 521st ranger battalion (Jägerbataillon 521) had been disbanded the rifles' memorial collection moved from Northeim to the Julius Leber Barracks of the Berlin Command (Standortkommando Berlin). The battalion's flag is preserved in the Military History Museum in Rastatt.

Commanders

Guards rifles battalion

_Garde-Sch%C3%BCtzen_Bataillon.jpg)

- 1814–1817: Major Charles-Gustave de Meuron[15]

- 1816: Major von Witzleben

- 1818: Major von Tilly

- 1829: Lieutenant Colonel von Grabowski

- 1830: Lieutenant Colonel von Thadden

- 1840: Lieutenant Colonel von Brandenstein

- 1847: Major von Arnim

- 1848: Lieutenant Colonel Eduard Vogel von Falckenstein

- 1850: Major von Thiesenhausen

- 1851: Lieutenant Colonel von Eberstein

- 1854: Lieutenant Colonel von Kalckstein

- 1860: Major von Bülow

- 1861: Lieutenant Colonel Hugo Falkenstein von Fabeck

- 1863: Lieutenant Colonel Knappe von Knappsteadt

- 1866: Lieutenant Colonel von Besser

- 1870: Lieutenant Colonel Hugo Falkenstein von Fabeck

- 1870: Lieutenant Colonel von Boeltzig

- 1879: Lieutenant Colonel von Nickisch-Rosenegk

- 1884: Lieutenant Colonel von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg

- 1888: Lieutenant Colonel von Scholten

- 1894: Lieutenant Colonel von Pawlowski

- 1897: Major von Roeder von Diersburg

- 1902: Major Arnold von Winckler

- 1906: Major von Helldorff

- 1909: Major Graf Finck von Finckenstein

- 1913: Major Bernhard von Gélieu (1864–1926)

- 1915: Major von Hadeln

- July 1916 – August 1918: Major Graf von Stosch

- August 1918 – November 1918: Major von Schierstädt

- November 1918: Captain Weiß (appointed, but did not take the command)

- December 1918: Captain von Arnim

Guards reserve rifles battalion

- 1914: Major Bronsart von Schellendorf

- 1916: Major Freiherr von Rotberg

- 1918: Captain Freiherr Treusch von Buttlar-Brandenfels

16th reserve ranger battalion

- 1 September 1914 – 5 October 1914: Major Freiherr von Werthern

- 25 October 1914 – 6 November 1914: Lieutenant Colonel Freiherr von Berlepsch

- 6 November 1914 – 9 November 1914: Feldwebel Lieutenant Muhme

- 9 November 1914 – 10 November 1914: Feldwebel Lieutenant Nausester

- 10 November 1914 – 15 November 1914: Vice Feldwebel Sieke

- 15 November 1914 – 19 November 1914: Lieutenant d.Res.a.D. Fiegen

- 19 November 1914 – 14 December 1914: Captain of the Landwehr von Maltitz

- 14 December 1914 – 11 July 1916: Captain of the Landwehr von Arnim

- 10 July 1916 – 4 September 1916: Major von Schuckmann

- 4 September 1916 – 9 September 1916: Lieutenant Colonel in the reserves retired Fiegen

- 9 September 1916 – 18 September 1916: Lieutenant Colonel in the reserves Bäumler

- 18 September 1916 – 26 September 1916: Captain in the reserves Stegner

- 26 September 1916 – 19 June 1917: Captain retired Korn

- 19 June 1917 – 20 June 1917: Captain in the reserves retired Fiegen

- 20 June 1918 – 22 July 1918: Captain Loesch

- 23 July 1918 – 6 August 1918: Lieutenant Colonel in the reserves Moser

- 6 August 1918 – 18 October 1918: Captain in the reserves Reimnitz

- 18 October 1918 – 19 October 1918: Lieutenant of the Landwehr Schmücker

- 19 October 1918 – 9 November 1918: Captain Pennrich

- 9 November 1918 – 31 December 1918: Captain von Ruville

Known members

- Karl von Bodelschwingh-Velmede (1800–1873), Prussian finance minister

- Lutz Heck (1892–1983), zoologist and director of the Berlin Zoo

- Robert Kempner (1899–1993), jurist and publisher, assistant chief prosecutor of the US at the Nuremberg Trials

- Ferdinand von Lüninck (1893–1944), politician (DNVP), upper president of the Province of Westphalia, member of the German resistance

- Hermann von Lüninck (1888–1974), politician (DNVP), upper president of the Rhine Province

- Hermann Joachim Pagels (1876–1959), sculptor

- Joachim Tiburtius (1889–1967), politician (CDU), senator for education in Berlin (1951–1963)

- Kurt Gustav Wilckens (1886–1923), anarchist, participant in the Patagonia Uprising

References

- Hans Henning von Alten et al., Geschichte des Garde-Schützen-Bataillons 1914–1919, Berlin: Deutscher Jägerbund, 1928

- Auguste Bachelin, Jean-Louis, Neuchâtel: Attinger Frères, 1895

- Alfred von Besser, Geschichte des Garde-Schützen-Bataillons, Berlin: Mittler & Sohn, 1910

- Carl Bleibtreu, Schlacht von Königgrätz am 3. Juli 1866, Stuttgart: Carl Krabbe, 1903 (reprint: Bad Langensalza: Rockstuhl, 2006, ISBN 978-3-938997-65-9)

- Alain Bauer, Denis Borel, Derck Engelberts, Antoine Grandjean, François Jeanneret et al., Écrivains Militaires de Suisse Romande, Hauterive: Gilles Attinger, 1988, ISBN 2-88256029-X

- Bernard de Gélieu, Causeries Militaires, Neuchâtel: Librairie J. Sandoz, 1877

- Alfred Guye, Le Bataillon de Neuchâtel dit des Canaris au Service de Napoléon 1807–1814, Neuchâtel: Editions de la Baconnière, à Boudry, 1964

- Arnold Freiherr von der Horst, Das Garde-Schützen-Bataillon, ein kurzer Abriss seiner Geschichte von der Stiftung bis zur Jetztzeit, Berlin: Mittler & Sohn, 1882

- Robert Kempner, Ankläger einer Epoche: Lebenserinnerungen, in collaboration with Jörg Friedrich, Frankfurt upon Main and Darmstadt: Ullstein, 1986, ISBN 3-548-33076-2.

- Hermann Lüders, Ein Soldatenleben in Krieg und Frieden, Stuttgart and Leipzig: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1888

- N.N., Die Erinnerungsfeier des Garde-Schützen-Bataillons an den Krieg 1870–1871, Berlin: R. Eisenschmidt, 1895

- Ilse Nicolas, „Militaria: Die Neffschandeller am Schlesischen Busch“, in: Ilse Nicolas, Kreuzberger Impressionen (11969), Berlin: Haude & Spener, 21979, (=Berlinische Reminiszenzen; vol. 26), pp. 111–114. ISBN 3-7759-0205-8

- Wolfgang Paul, Das Potsdamer Infanterieregiment 9 1918–1945, Osnabrück: Biblio, 1983

- Cyrill Soschka, Wer dann die Sonne noch sieht, Munich: Karl Thiemig, 1974, ISBN 3-521-04055-0

- Wolfgang von Stephani, Festschrift zur Feier des hundertjährigen Bestehens des Garde-Schützen-Bataillons, Berlin: R. Eisenschmidt, 1914.

- Paul de Vallière, Honneur et Fidélité: Histoire des Suisses au service étranger, Neuchâtel: F. Zahn, 1913 (reprint: Lausanne: Editions d’art ancien suisse, 1940).

- Eugène Vodoz, Le Bataillon Neuchâtelois des Tirailleurs de la Garde de 1814 à 1848, Neuchâtel: Attinger Frères, 1902

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Garde-Schützen-Bataillon. |

- Weiterleitung Information on the Guards Rifles Battalion

Notes

- Nicolas, see references for details, p. 111.

- His uncle Charles-Daniel de Meuron had sponsored his studies at Frederick the Great's 1765-founded Académie des nobles (aka Académie militaire) in Berlin, precursor of the Prussian Military Academy, before he joined the Prussian army, quitting in 1804. Cf. Cyrille Gigandet: Meuron, Charles-Gustave de in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland., retrieved on 11 April 2017.

- Nicolas, see references for details, p. 113.

- Nicolas, see references for details, p. 112.

- Since 1813 commoners with a high school degree (such as mittlere Reife or Abitur) could apply for a one-year volunteer service allowing them an officer career in a military unit of their choice.

- Stephani, see references for details, p. 10.

- In Berlin a street was named after him. Cf. "Gélieustraße", on: Kauperts Straßenführer durch Berlin, retrieved on 5 July 2012

- Derck Engelberts: Gélieu, Bernard de in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland., retrieved on 11 April 2017.

- Kempner, see references for details, p. 22.

- Sibylle Badstübner-Gröger, Michael Bollé, Ralph Paschke et al., Handbuch der Deutschen Kunstdenkmäler / Georg Dehio: 22 vols., revis. and ext. new ed. by Dehio-Vereinigung, Berlin and Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 22000, vol. 8: Berlin, p. 404. ISBN 3-422-03071-9.

- Nicolas, see references for details, p. 114.

- Cf. the image of "Eigentumsstück Waffenrock Preußen Garde-Schützen-Batl.", on: Kaiser's Bunker, retrieved on 5 July 2012.

- Cf. the above-mentioned battle painting of the Battle of Königgrätz by Christian Sell.

- Hsi-Huey Liang, Die Berliner Polizei in der Weimarer Republik [The Berlin police force in the Weimar Republic, Berkeley, London, Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1970; German], Berlin and New York: de Gruyter, 1977, (=Veröffentlichungen der Historischen Kommission zu Berlin; vol. 47), p. 72. ISBN 3-11-006520-7.

- Later he served as Prussian minister to Switzerland (1820–1824), Bavaria and Denmark (1826–1830). Cf. Cyrille Gigandet: Meuron, Charles-Gustave de in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland., retrieved on 11 April 2017.