Guðrøðr Rǫgnvaldsson

Guðrøðr Rǫgnvaldsson (died 1231), also known as Guðrøðr Dond, was a thirteenth-century ruler of the Kingdom of the Isles.[note 1] He was a member of the Crovan dynasty, and a son of Rǫgnvaldr Guðrøðarson, King of the Isles, the eldest son of Guðrøðr Óláfsson, King of Dublin and the Isles. Although the latter may have intended for his younger son, Óláfr, to succeed to the kingship, the Islesmen instead settled upon Rǫgnvaldr, who went on to rule the Kingdom of the Isles for almost forty years. The bitterly disputed royal succession divided the Crovan dynasty for three generations, and played a central role in Guðrøðr's recorded life.

| Guðrøðr Rǫgnvaldsson | |

|---|---|

| King of the Isles | |

.jpg) Guðrøðr's name as it appears on folio 42v of British Library Cotton Julius A VII (the Chronicle of Mann): "Godredus".[1] | |

| Died | 1231 Lewis and Harris |

| Issue | Haraldr Guðrøðarson |

| House | Crovan dynasty |

| Father | Rǫgnvaldr Guðrøðarson |

Guðrøðr's mother was Rǫgnvaldr's wife. Whilst the name of this woman is unknown, she appears to have been a member of the Clann Somhairle kindred. Although Rǫgnvaldr was able to orchestrate a marriage between Óláfr and her sister, Óláfr was able to oversee the nullification this alliance and proceeded to marry the daughter of a leading Scottish magnate. In consequence, Guðrøðr's mother ordered her son to attack Óláfr. Although Guðrøðr is recorded to have ravaged Óláfr's lands on Lewis and Harris, the latter was able to escape to the protection of his father-in-law on the Scottish mainland. In about 1223, Óláfr, and his adherent Páll Bálkason, invaded Skye, defeated Guðrøðr, and blinded and castrated him.

Guðrøðr's maiming marks a turning point in the feud between Rǫgnvaldr and Óláfr. With the escalation of hostilities, Rǫgnvaldr bound himself to Alan fitz Roland, Lord of Galloway. Although Rǫgnvaldr was greatly aided by Alan's military might, Óláfr eventually gained the upper-hand, and Rǫgnvaldr was slain in 1229. Afterwards, Alan and his Clann Somhairle allies continued to pressure Óláfr, forcing him from the Isles to Norway where news of the continual warfare had already reached Hákon Hákonarson, King of Norway. As a result, Hákon elevated an apparent Clann Somhairle dynast, a certain Óspakr, as King of the Isles, and outfitted him with a fleet to secure control of the Isles.

Guðrøðr seems to have been one of Óspakr's principal supporters, and accompanied him in the ensuing campaign that reached the Isles in 1230. Óspakr seems to succumbed to injuries suffered in the midst of the operation after which command fell to Óláfr. Although the latter proceeded to divert the fleet to Mann where he was reinstalled as king, Guðrøðr was recognised as king of the Hebridean portion of the realm. The following year, after the Norwegians vacated the Isles, both Guðrøðr and Páll are reported to have been killed. Although Óláfr consolidated control of the entirety of the Crovan dynasty's realm, ruling it for the rest of his life, Guðrøðr's son, Haraldr, continued the dynastic feud with Óláfr's successors, and temporarily held the kingship at the midpoint of the century.

Antecessors

.png)

Guðrøðr was a son of Rǫgnvaldr Guðrøðarson, King of the Isles,[23] and a member of the Crovan dynasty.[24] Guðrøðr's mother was Rǫgnvaldr's wife,[25] a woman who is styled Queen of the Isles by the thirteenth- to fourteenth-century Chronicle of Mann.[26] Although her parentage is uncertain,[27] the chronicle describes her father as a nobleman from Kintyre,[28] which suggests that he was a member of Clann Somhairle.[29] Rǫgnvaldr was a son of Guðrøðr Óláfsson, King of Dublin and the Isles.[30] Other children of this ruler include Affrica,[31] Ívarr,[32] Óláfr,[33] a daughter whose name is unknown,[34] and possibly a son named Ruaidhrí.[24]

Whilst Óláfr's mother was Fionnghuala Nic Lochlainn,[36] an Irishwoman whose marriage to Guðrøðr Óláfsson was formalised (at about the time of Óláfr's birth) in 1176/1177,[37] Rǫgnvaldr's mother appears to have been another Irishwoman named Sadbh.[38] When Guðrøðr Óláfsson died in 1187, the chronicle reports that he left instructions for Óláfr to succeed to the kingship since the latter had been born "in lawful wedlock".[39] Whether this is an accurate record of events is uncertain,[40] as the Islesmen are stated to have chosen Rǫgnvaldr to rule instead, because unlike Óláfr, who was only a child at the time, Rǫgnvaldr was a hardy young man fully capable to reign as king.[41] The fact that Rǫgnvaldr and Óláfr had different mothers may well explain the intense conflict between the two men in the years that followed.[42] This continuing kin-strife is one of the main themes of Rǫgnvaldr's long reign.[43]

_(14496303221).jpg)

At some point after assuming control of the kingdom, the chronicle reports that Rǫgnvaldr gave Óláfr possession of a certain island called "Lodhus".[48] Whilst the name of this island appears to refer to Lewis—the northerly half of the Outer Hebridean island of Lewis and Harris—the chronicle's text seems to instead refer to Harris—the southerly half.[49] In any case, the chronicle further relates that Óláfr later confronted Rǫgnvaldr for a larger share of the realm, after which Rǫgnvaldr had him seized and sent to William I, King of Scotland, who kept him imprisoned for almost seven years until about the time of the latter's death in 1214.[50] Since William died in December 1214, Óláfr's incarceration appears to have spanned between about 1207/1208 and 1214/1215.[51] Upon Óláfr's release, the chronicle reveals that the half-brothers met on Mann, after which Óláfr set off on a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela.[52]

Scandinavian sojourn

.jpg)

In 1210, Rǫgnvaldr appears to have found himself the target of renewed Norwegian hegemony in the Isles.[55] Specifically, the Icelandic annals reveal that a military expedition from Norway to the Isles was in preparation in 1209. The following year, the same source makes note of "warfare" in the Isles, and specifies that the holy island of Iona was pillaged.[56] These reports are corroborated by Bǫglunga sǫgur, a thirteenth-century saga-collection that survives in two versions. Both versions reveal that a fleet of Norwegians plundered in the Isles, and the shorter version notes how men of the Birkibeinar and the Baglar—two competing sides of the Norwegian civil war—decided to recoup their financial losses with a twelve-ship raiding expedition into the Isles.[57] The longer version states that "Ragnwald" (styled "Konge aff Möen i Syderö") and "Gudroder" (styled "Konge paa Manö") had not paid their taxes due to the Norwegian kings. In consequence, the source records that the Isles were ravaged until the two travelled to Norway and reconciled themselves with Ingi Bárðarson, King of Norway, whereupon the two took their lands from Ingi as a lén (fief).[58]

.jpg)

The two submitting monarchs of the saga most likely represent Rǫgnvaldr and Guðrøðr.[60][note 4] Their submission appears to have been undertaken in the context facing the strengthening position of the Norwegian Crown following the settlement between the Birkibeinar and Baglar,[64] and the simultaneous weakening of the Crovan dynasty due to internal infighting.[65] The destructive Norwegian activity in the Isles may have been some sort of officially sanctioned punishment from Norway due to Rǫgnvaldr's recalcitrance in terms of, not only his Norwegian obligations, but his recent reorientation towards the English Crown.[66] The fact that Ingi turned his attention to the Isles so soon after peace was brokered in Norway may well indicate the importance that he placed on his relations with Rǫgnvaldr and his contemporaries in the Isles.[67][note 5] There is reason to suspect that Óláfr had earlier approached Ingi in an attempt to garner support in gaining his perceived birthright before Rǫgnvaldr was able to have Óláfr imprisoned by the Scots.[69] With Óláfr thus neutralised, Rǫgnvaldr could well have submitted to the Norwegian Crown in the context of further securing his hold of the kingship.[70] In any event, the albeit confused titles accorded to Rǫgnvaldr and Guðrøðr by the saga seem to reveal that Guðrøðr possessed some degree of power in the Isles by the early thirteenth century.[71]

Kin-strife

Upon Óláfr's return from his pilgrimage, the chronicle records that Rǫgnvaldr had Óláfr marry "Lauon", the sister of his own wife. Rǫgnvaldr then granted Lodhus back to Óláfr, where the newly-weds proceeded to live until the arrival of Reginald, Bishop of the Isles. The chronicle claims that the bishop disapproved of the marriage on the grounds that Óláfr had formerly had a concubine who was a cousin of Lauon. A synod was then assembled, after which the marriage is stated to have been nullified.[73] Although the chronicle alleges that Óláfr's marriage was doomed for being within a prohibited degree of kinship, there is reason to suspect that the real reason for its demise was the animosity between the half-brothers.[74] Once freed from his arranged marriage, Óláfr proceeded to marry Cairistíona, daughter of Fearchar mac an tSagairt,[75] a man closely aligned with Alexander II, King of Scotland.[76][note 6]

If the chronicle is to be believed, Óláfr's separation from Lauon enraged her sister—the wife of Rǫgnvaldr and mother of Guðrøðr—who surreptitiously tricked Guðrøðr into attacking Óláfr in 1223. Following what he thought were his father's orders, Guðrøðr gathered a force on Skye[88]—where he was evidently based[89][note 7]—and proceeded to Lodhus, where he is reported to have laid waste to most of the island. Óláfr is said to have only narrowly escaped with a few men, and to have fled to the protection of his father-in-law on the mainland in Ross. Óláfr is stated to have been followed into exile by Páll Bálkason, a vicecomes on Skye who refused to take up arms against him.[88] At a later date, Óláfr and Páll are reported to have returned to Skye and defeated Guðrøðr in battle.[91][note 8]

.jpeg)

The chronicle specifies that Guðrøðr was overcome on "a certain island called the isle of St Columba".[96] This location may be identical to Skeabost Island in the mouth of the river Snizort (NG41824850).[97] Another possibility is that the isle in question is the now-landlocked island of Eilean Chaluim Chille in the Kilmuir district (NG37706879).[98] This island once sat in Loch Chaluim Chille before the loch was drained of water and turned into a meadow.[99] There is archaeological evidence to suggest that a fortified site sat on another island in the loch, and that this islet was connected to the monastic island by a causeway. If correct, the fortification could account for Guðrøðr's presence near an ecclesiastical site.[100] According to the chronicle, Óláfr's forces consisted of five boats, and encircled the island after having launched from the opposite shore two stadia from it. This distance, about 2 furlongs (400 metres), suggests that the island is more likely Eilean Chaluim Chille than Skeabost Island, as the former appears to have sat between 285 metres (935 feet) and 450 metres (1,480 feet) from the surrounding shores of Loch Chaluim Chille.[101][note 9] In any case, in consequence of the defeat, Guðrøðr's captured followers were put to death, whilst Guðrøðr himself was blinded and castrated.[91] It is possible that Óláfr was aided by Fearchar in the strike against Guðrøðr.[107] Certainly, the chronicle's account seems to suggest that Óláfr accumulated his forces whilst sheltering in Ross.[108] Although the chronicle maintains that Óláfr was unable to prevent this torture, and specifically identifies Páll as the instigator of the act,[109] the Icelandic annals record that Óláfr was indeed responsible for his nephew's plight, and make no mention of Páll.[110][note 10]

.jpg)

The mutilation and killing of high status kinsmen during power-struggles was not an unknown phenomenon in the peripheral-regions of the British Isles during the High Middle Ages.[112][note 11] For instance, in only the century-and-a-half of its existence, at least nine members of the Crovan dynasty perished from mutilation or assassination.[114] For instance, in only the century-and-a-half of its existence, at least nine members of the Crovan dynasty perished from mutilation or assassination.[115] As such, there is reason to regard this vicious internecine violence as the Crovan dynasty's greatest weakness.[116] To contemporaries, the tortures of blinding and emasculation were a means of depriving power from a political opponent. Not only would the punishment deny a man the ability to sire descendants, it would divest him of personal power, limiting his ability to attract supporters, and further offset the threat of future vengeance.[117] The maiming inflicted upon Guðrøðr seems to exemplify Óláfr's intent to wrest his perceived birthright from Rǫgnvaldr's bloodline. It is unknown why Rǫgnvaldr did not similarly neutralise Óláfr when he had the chance years before, although it may have had something to do with the preservation of international relations. For example, it is possible that his act of showing leniency to Óláfr had garnered Scottish support against the threat of Norwegian overlordship.[118] In any case, the neutralisation of Guðrøðr appears to mark a turning point in the struggle between the Óláfr and Rǫgnvaldr.[119]

Escalation of warfare

In 1224, the year following Guðrøðr's defeat, the chronicle reveals that Óláfr took hostages from the leading men of the Hebridean portion of the realm, and confronted Rǫgnvaldr on Mann directly. It was then agreed that the kingdom would be split between the two: with Rǫgnvaldr keeping Mann itself along with the title of king, and Óláfr retaining the a share in the Hebrides.[121][note 12] With Óláfr's rise at Rǫgnvaldr expense, the latter turned to Alan fitz Roland, Lord of Galloway,[125] one of Scotland's most powerful magnates.[126] Whilst the pair are elsewhere stated to have campaigned in the Hebrides,[127] the chronicle recounts that their operations came to nought because the Manx were unwilling to battle against Óláfr and the Hebrideans.[128]

A short time later, perhaps in about 1225 or 1226, the chronicle reveals that Rǫgnvaldr oversaw the marriage of a daughter of his to Alan's young illegitimate son, Thomas. Unfortunately for Rǫgnvaldr, this marital alliance appears to have cost him the kingship, since the Manxmen are further reported to have had him removed from power and replaced with Óláfr.[132] The recorded resentment of the union could indicate that Alan's son was intended to eventually succeed Rǫgnvaldr,[133] who had reigned for almost forty years and was perhaps about sixty years-old at the time,[134] and whose grandchildren were presumably still very young.[118] In fact, it is possible that, in light of Rǫgnvaldr's advanced age and Guðrøðr's maiming, a significant number of the Islesmen regarded Óláfr as the rightful heir. Such a view could well account for the lack of enthusiasm that the Manxmen had for Alan and Rǫgnvaldr's campaign in the Hebrides.[135] Since Thomas was likely little more than a teenager at the time, it may well have been obvious to contemporary observers that Alan was the one who would hold the real power in the kingdom.[136]

At this low point of his career, the deposed Rǫgnvaldr appears to have gone into exile at Alan's court in Galloway.[142] In 1228, whilst Óláfr and his chieftains were absent in Hebrides, Rǫgnvaldr, Alan, and (Alan's brother) Thomas fitz Roland seized control of Mann.[143] Suffering serious setbacks at the hands of his opponents, Óláfr reached out for English assistance against his half-brother,[144] and eventually regained possession of the island.[145] In what was likely early January 1229, Rǫgnvaldr successfully invaded Mann.[146] According to the chronicle, Rǫgnvaldr and Óláfr led their armies to Tynwald, where Rǫgnvaldr's forces were routed with Rǫgnvaldr amongst the slain.[147] Although the latter's fall is laconically corroborated by the Icelandic annals,[148] other sources appear to suggest that his death was due to treachery. The fourteenth-century Chronicle of Lanercost, for example, states that Rǫgnvaldr "fell a victim to the arms of the wicked";[149] whilst the Chronicle of Mann notes that, although Óláfr grieved at his half-brother's death, he never exacted vengeance upon his killers.[147] Although the chronicle's accounts of Guðrøðr's maiming and Rǫgnvaldr's death could be evidence that Óláfr was unable to control his supporters during these historical episodes, it is also possible that the compilers of this source sought to disassociate Óláfr from these acts of violence against his kin.[150]

Invasion of the Isles

The death of Alan's ally did not deter Gallovidian interests in the Isles. In fact, it is apparent that Alan and members of the Clann Dubhghaill branch of Clann Somhairle upheld pressure upon Óláfr.[153] Reports of open warfare in the Isles reached the royal court of Hákon Hákonarson, King of Norway in the summer of 1229.[154] The thirteenth-century Hákonar saga Hákonarsonar specifically singles out Alan as one of the principal perpetrators of unrest in the Isles,[155] along with several members of Clann Somhairle: Dubhghall mac Dubhghaill, Donnchadh mac Dubhghaill, and a certain Somhairle.[156] Although Óláfr arrived at the Norwegian court early in 1230, having been forced from the Isles by Alan and his allies, it is evident that Hákon had already decided upon a course of action.[157]

.jpg)

The Icelandic annals, the Chronicle of Mann, the saga, and the Chronicle of Lanercost all reveal that Hákon handed over the kingship of the Isles to Óspakr,[159] an apparent member of Clann Dubhghaill who had long served outwith the Isles in Norway.[160] Other Islesmen in Norway before Óláfr's arrival were Páll and Guðrøðr,[118] the latter who seems to have been one of Óspakr's principal supporters.[161][note 14] According to saga, Hákon not only granted Óspakr the kingship, but also gave him command of the Norwegian fleet tasked with restoring peace in the Isles.[170] Within days of Óláfr's arrival in Norway, the saga reveals that Óspakr's fleet set sail for the Isles, and swelled in number after reaching Orkney.[171] Whilst the Eirspennill version of the saga numbers the fleet in Norway at twelve ships, the Flateyjarbók, Frísbók, and Skálholtsbók versions give the number eleven;[172] and whilst the former version relates that the fleet gained twenty ships from Orkney, the latter three versions state that the fleet numbered twenty when it left Orkney.[173][note 15] Once in the Isles, the fleet linked up with three leading members of Clann Somhairle on Islay.[177]

News of the gathering Norwegian fleet soon reached Alexander II, who appears to have made straight for the western coast, diverting his attention to the now rapidly developing crisis. On 28 May, Alan is recorded in Alexander II's presence at Ayr, where the Scottish royal forces appear to have assembled.[180] It was probably May or June when Óspakr's fleet rounded the Mull of Kintyre, entered the Firth of Clyde, and made landfall on Bute, where his forces successfully stormed and captured a fortress that is almost certainly identical to Rothesay Castle.[181] The Flateyjarbók, Frísbók, and Skálholtsbók versions of the saga specify that the castle fell after three days of battle,[182] and that three hundred Norwegians and Islesmen fell in the assault.[183] By this stage in the campaign, the fleet is stated to have reached a size of eighty ships,[184] a tally which may indicate that Óspakr's fighting-force numbered over three thousand men.[185] Reports that Alan was in the vicinity, at the command of a massive fleet, are stated to have forced the Norwegians to withdraw to Kintyre.[186] Whilst the Eirspennill version of the saga numbers Alan's fleet at almost two hundred ships, the Flateyjarbók, Frísbók, and Skálholtsbók versions give a tally of one hundred and fifty.[187] These totals suggest that Alan commanded a force of two thousand[188] or three thousand men.[189]

Having withdrawn his fleet to Kintyre, Óspakr took ill and died,[193] presumably succumbing to injuries sustained from the assault on Bute.[194] According to the saga, the king's death was bitterly lamented amongst his followers.[195] In consequence of Óspakr's fall, the Chronicle of Lanercost, the Chronicle of Mann, and the saga reveal that command of the fleet was assumed by Óláfr, who successfully eluded Alan's forces, and capitalised upon the situation by diverting the armada to Mann. Although Óláfr succeeded in being reinstated as king after overwhelming some initial opposition, he was nevertheless forced to partition the realm with Guðrøðr, who took up kingship in the Hebrides.[196]

Despite Óspakr's elevation as king, it is uncertain how Hákon envisioned the governance of the Kingdom of the Isles. On one hand, it is possible that Hákon intended for Óspakr and Guðrøðr to divide the kingdom at Óláfr's expense.[197] On the other hand, the fact that Óláfr's struggle against Alan and Clann Somhairle is acclaimed by the saga could be evidence that Hákon did not intend to replace Óláfr with Óspakr. Instead, Hákon may have planned for Óspakr to reign over the sprawling domain of Clann Somhairle as a way to ensure the kindred's obedience. Óspakr's prospective realm, therefore, seems to have comprised Argyll, Kintyre, and the Inner Hebrides.[198] If correct, the fleet's primary design would appear to have been the procurement of Óspakr's domain, whilst a secondary objective—adopted very late in the campaign—seems to have been the restoration of Óláfr on Mann.[199]

.jpg)

It is also possible that Hákon originally ordered a division of power between Óláfr and Guðrøðr,[200] and that Hákon originally promised to lend support to Óláfr's cause on the condition of a concession of authority to Guðrøðr,[201] who—like Óspakr—could have been recognised as king by the Norwegian Crown.[202] An accommodation between Óláfr and Guðrøðr could well have benefited both men, as it would have safeguarded their kindred against the dynastic ambitions of Alan, offsetting the royal marriage between this man's son and Guðrøðr's sister.[203] In any case, the Chronicle of Mann and the saga reveal that the Norwegian forces left Mann for home in the following spring, and established Guðrøðr in the Hebrides. Before the end of 1231, both Páll and Guðrøðr are reported to have been killed. Whilst the saga merely locates Guðrøðr's death to the Suðreyjar[204]—an Old Norse term roughly equating to the Hebrides and Mann[205]—the chronicle specifically locates the incident on Lodhus.[204]

Upon the homeward return of the Norwegians, the saga declares that Hákon's "honours had been won" as a result of the expedition, and that he himself heartily thanked the men for their service.[206] The operation itself seems to mark a turning point in the history of the Kingdom of the Isles. Although the kings that ruled the realm before Rǫgnvaldr could afford to ignore Norwegian royal authority, it is apparent that those who ruled after him required a closer relationship with the Norwegian Crown.[207] Óláfr went on to rule the realm until his death in 1237.[208] Although Scottish sources fail to note the Norwegian campaign, its magnitude is revealed by English sources such as the Chronicle of Lanercost,[209] and the thirteenth-century Annales de Dunstaplia, with the latter reporting that the campaigning Norwegians and Islesmen were only overcome with much labour after they had invaded Scotland and Mann and inflicted considerable casualties.[210]

_2.jpg)

The context of Guðrøðr's final fall suggests that, despite his injuries and impairment, he was able to swiftly assert his authority and eliminate Páll.[211] Although the Norwegians' presence may have temporarily constrained the implacable animosities of the Islesmen, the fleet's departure appears to have been the catalyst of renewed conflict.[118] Evidently still an adherent of Óláfr—certainly, the two are reported to have sailed on the same ship on the outset of Óspakr's campaign[212]—Páll's annihilation suggests that Guðrøðr avenged his father's destruction and his own mutilation.[213] The fact that Óláfr was able to regain and retain control of the realm after Guðrøðr's demise suggests that Óláfr may have moved against him once the Norwegians left the region.[118]

Óláfr was succeeded by his son, Haraldr,[214] who was in turn succeeded by another son, Rǫgnvaldr.[215] This monarch was slain in 1249, seemingly by an associate of Guðrøðr's son, Haraldr, whereupon the latter assumed the kingship.[216] This abrupt seizure of royal power by Guðrøðr's son—almost twenty years after Guðrøðr's death—exposes the fact that the inter-dynastic strife between lines of (Guðrøðr's father) Rǫgnvaldr and Óláfr carried on for yet another generation.[217] The infighting only came to an end in the reign of the dynasty's final monarch, Óláfr's son, Magnús.[218]

Notes

- Since the 1980s, academics have accorded Guðrøðr various personal names in English secondary sources: Godfred,[2] Godfrey,[3] Godred,[4] Gofraid,[5] Guðrøð,[6] Guðrǫðr,[7] and Guðrøðr.[8] During the same period, Guðrøðr has been accorded various epithets in English secondary sources: Godfrey Donn,[9] Godfrey the Black,[10] Godred Don,[11] Godred don,[12] Godred Dond,[13] Godred the Brown-haired,[14] Gofraid Donn,[5] Guðrøð the Black,[6] Guðrøðr Don,[15] Guðrøðr 'Don',[16] and Guðrøðr Dond.[17] Since the 1990s, academics have accorded Guðrøðr various patronyms in English secondary sources: Godred Ranaldson,[18] Godred Rognvaldsson,[19] Guðrøð Rǫgnvaldsson,[6] Guðrøðr Rögnvaldarson,[20] Guðrøðr Rǫgnvaldsson,[21] and Guðrǫðr Rǫgnvaldsson.[22]

- Comprising some four sets,[45] the pieces are thought to have been crafted in Norway in the twelfth- and thirteenth centuries.[46] They were uncovered in Lewis in the early nineteenth century.[47]

- The Scandinavian connections of leading members of the Isles may have been reflected in their military armament, and could have resembled that depicted upon such gaming pieces.[54]

- Another possibility is that the two named kings instead refer to Rǫgnvaldr's like-named first cousin, Raghnall mac Somhairle, and Rǫgnvaldr himself.[61] This identification rests on that fact that Raghnall and Rǫgnvaldr bore the same personal names[62]—the Gaelic Raghnall is an equivalent of the Old Norse Rǫgnvaldr[63]—coupled with the possibility that the source's "Gudroder" is the result of confusion regarding Rǫgnvaldr's patronym.[62]

- The longer version of the saga also relates that a fleet of Norwegians made landfall in Shetland and Orkney, whereupon Bjarni Kolbeinsson, Bishop of Orkney, and the two co-earls of Orkney—Jón Haraldsson and Davið Haraldsson—were compelled to journey to Norway and submit to Ingi rendering him hostages and a large fine.[68]

- The father of Rǫgnvaldr's wife and Lauon may well have been either Raghnall,[77] or Raghnall's son, Ruaidhrí[78]—both of whom appear to have been styled "Lord of Kintyre" in contemporary sources[79]—or possibly even Raghnall's younger son, Domhnall.[80] In 1221/1222, Alexander II seems to have overseen a series of invasions into Argyll,[81] The king's campaign appears to have resulted in a local regime change, with Ruaidhrí being replaced by Domhnall in Kintyre.[82] Óláfr's concurrent matrimonial realignment with Fearchar could well have been influenced by Scots' royal campaign against Ruaidhrí.[83] One reason why the chronicle fails to name the father-in-law of Rǫgnvaldr and Óláfr could be that the chronicle is biased against him. Another possibility is that the chronicler may have simply not known his name.[84] Likewise, the fact that the chronicle fails to name Lauon's sister—a woman alleged to have played a significant role in the kin-strife between Rǫgnvaldr and Óláfr—could be evidence of a specific bias against her.[85]

- There is reason to suspect that the record of Guðrøðr on Skye indicates that he possessed the island in the context of acting as Rǫgnvaldr's heir-apparent. If correct, Rǫgnvaldr's earlier grant of Lodhus to Óláfr could indicate that Óláfr had previously been recognised as Rǫgnvaldr's heir. On the other hand, this grant may have merely been given in the context of appeasing a disgruntled dynast passed over for the kingship.[90]

- The chronicle describes Páll as a vicecomes. This Latin term has been translated into English as "sheriff",[92] but may represent a Scandinavian title.[93] It is possible that the term vicecomes is utilised as a result of English and Scottish influences in the Isles.[94] In any case, the chronicle's account of Páll reveals that he was an important figure in the Isles—describing him as a "vigorous and powerful man throughout the kingdom"[95]—and appears to indicate that he acted as a royal representative on Skye.[93]

- The fact that, according to local tradition in Kilmuir, Páll or his father appears to be traditionally associated with the district[102]—and called in Gaelic Fear Caisteal Eilein Chaluim Chille ("the man of the castle of Eilean Chaluim Chille")[103]—may confirm that Loch Chaluim Chille was indeed the site of Guðrøðr's stand against Óláfr and Páll.[2] Kilmuir is also the site of Blar a' Bhuailte ("the field of the stricken"), where Vikings are traditionally said to have made a last stand in battle on Skye.[104] Whilst the name of the island could suggest that the chronicle refers to Iona,[105] the most famous island associated with St Columba, the context of passage reveals that the events took place on Skye.[106]

- Guðrøðr's defeat to Óláfr and Páll is also noted—albeit in an extremely garbled form—by the seventeenth-century Sleat History.[111]

- According to the twelfth-century Descriptio Kambriæ, in an English account of succession dispute disputes among the Welsh, "the most frightful disturbances occur in their territories as a result, people being murdered, brothers killing each other and even putting each other's eyes out, for as everyone knows from experience it is very difficult to settle disputes of this sort".[113]

- Also that year, the thirteenth-century Hákonar saga Hákonarsonar reports that a certain Gillikristr, Óttar Snækollsson, and many Islesmen, travelled to Norway and presented Hákon Hákonarson, King of Norway with letters pertaining to the needs of their lands.[122] One possibility is that these so-called needs refer to the violent kin-strife and recent treaty between the half-brothers.[123] The saga may therefore reveal that the Norwegian Crown was approached by either representatives of both sides of the inter-dynastic conflict, or perhaps by neutral chieftains caught in the middle.[124]

- Much of the visible site dates only to the eighteenth-, nineteenth-, and twentieth century.[137] The first specific record of Tynwald as an assembly site dates to 1237.[141]

- Whilst this man is probably identical to Guðrøðr, there is reason to suspect that he could have been an otherwise unrecorded like-named brother.[162] For example, it is only at about this point that the Chronicle of Mann accords Guðrøðr an epithet.[163] Guðrøðr is accorded several epithets by numerous sources. For instance, the chronicle gives Don, an epithet derived from the Gaelic donn ("brown"),[164] and means "brown" or "brown-haired".[152] Guðrøðr's like-named great-great grandfather, Guðrøðr Crovan, King of Dublin and the Isles, is also accorded several Gaelic epithets.[165] Such names partly evidence the significant Gaelic influence upon the Scandinavian aristocracy of the Isles.[166] Hákonar saga Hákonarsonar accords Guðrøðr an epithet meaning "black".[167] Whether this source has confused the Gaelic donn for dubh ("black"),[168] or confused Guðrøðr with another man, is unknown.[169] Much like the saga, the Sleat History identifies Guðrøðr as "the black".[111]

- Hákonar saga Hákonarsonar exists in several mediaevel redactions.[174] The most authoritative of these is the Eirspennill version.[175] Whilst the fleet was Orkney, the saga reports that a detachment of ships, led by Páll's son, Bálki, and a certain Óttarr Snækollr, journeyed to Skye where they fought and killed Þórkell Þórmóðarson, in what may have been the culmination of a family feud.[176] If word of Óspakr's royal fleet had not reached Alan and the Scots at the time of its arrival at Orkney, news of it could well have been passed on from Fearchar when the Islesmen clashed at Skye.[118]

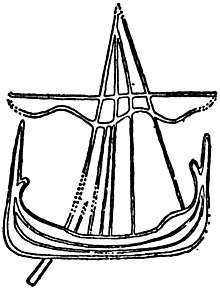

- This coat of arms is blazoned: gules, three galleys with dragon heads at each end or, one above the other.[191] The coat of arms concerns Hákon's coronation, and its associated caption reads in Latin: "Scutum regis Norwagiae nuper coronati, qui dicitur rex Insularum".[190] The coat of arms was illustrated by Matthew Paris, a man who met Hákon in 1248/1249, the year after the king's coronation. The emphasise that Matthew placed upon the Norwegian realm's sea power appears to be underscored in the heraldry he attributed to Hákon.[192]

Citations

- Munch; Goss (1874) p. 86; Cotton MS Julius A VII (n.d.).

- Sellar (1997–1998).

- McDonald (2008); Barrow (2006); MacLeod (2002); Sellar (2000); Sellar; Maclean (1999); Sellar (1997–1998); McDonald (1997).

- McDonald (2019); Ó Cróinín (2017); Cochran-Yu (2015); Crawford (2014); Thomas (2014); Crawford (2013); Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005); McNamee (2005); Power (2005); Duffy (2004); Broderick (2003); Oram (2000); Fellows-Jensen (1998); Oram (1988); Sawyer (1982); Matheson (1978–1980).

- Veach (2014).

- Williams (1997).

- Beuermann (2011); Steinsland; Sigurðsson; Rekdal et al. (2011).

- McDonald (2016); Oram (2013); McDonald (2012); Oram (2011); Beuermann (2010); Downham (2008); McDonald (2007b); Woolf (2007); Gade (1994).

- Barrow (2006); MacLeod (2002); Sellar (2000); Sellar; Maclean (1999); Sellar (1997–1998).

- Barrow (2006).

- McDonald (2019); Ó Cróinín (2017); McNamee (2005); Broderick (2003); Fellows-Jensen (1998); Oram (1988); Matheson (1978–1980).

- Power (2005).

- Cochran-Yu (2015); Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005); Duffy (2004); Oram (2000).

- Duffy (2004).

- McDonald (2012); McDonald (2007b).

- McDonald (2016).

- Oram (2011).

- Cochran-Yu (2015).

- McDonald (2019); Oram (2000).

- Oram (2013).

- Beuermann (2010); Gade (1994).

- Veach (2014); Steinsland; Sigurðsson; Rekdal et al. (2011).

- McDonald (2019) p. ix tab. 1; McDonald (2007b) p. 27 tab. 1; Power (2005) p. 34 tab.; MacLeod (2002) p. 275 tab.; Sellar (2000) p. 192 tab. i; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 200 tab. ii; Anderson (1922) p. 467 n. 2. tab.

- McDonald (2007b) p. 27 tab. 1.

- Oram (2013) ch. 4; Sellar (1997–1998).

- McDonald (2007b) pp. 79, 163; Anderson (1922) p. 458; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 86–87.

- McDonald (2019) pp. 60–61; Oram (2013) ch. 4; McDonald (2007b) pp. 116–117.

- McDonald (2019) pp. 60, 66; Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 36; Oram (2013) ch. 4; McDonald (2007a) p. 73 n. 35; McDonald (2007b) pp. 78, 116; Woolf (2007) p. 81; Pollock (2005) p. 27 n. 138; Duffy (2004); Woolf (2003) p. 178; McDonald (1997) p. 85; Anderson (1922) p. 457; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 84–85.

- McDonald (2019) pp. 60–61; McDonald (2007a) p. 73 n. 35; Woolf (2007) p. 81.

- McDonald (2019) p. ix tab. 1; McDonald (2007b) p. 27 tab. 1; McNamee (2005); Duffy (2004); Sellar (2000) p. 192 tab. i.

- McDonald (2019) p. ix tab. 1; McDonald (2007b) p. 27 tab. 1; Power (2005) p. 34 tab.; Sellar (2000) p. 192 tab. i; Anderson (1922) p. 467 n. 2. tab.

- McDonald (2007b) p. 27 tab. 1; Anderson (1922) p. 467 n. 2. tab.

- McDonald (2019) p. ix tab. 1; Oram (2011) p. xvi tab. 5; McDonald (2007b) p. 27 tab. 1; Power (2005) p. 34 tab.; Brown, M (2004) p. 77 tab. 4.1; MacLeod (2002) p. 275 tab.; Sellar (2000) p. 192 tab. i; McDonald (1997) p. 259 tab.; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 200 tab. ii; Anderson (1922) p. 467 n. 2. tab.

- Power (2005) p. 34 tab.; Anderson (1922) p. 467 n. 2 tab.

- Munch; Goss (1874) p. 78; Cotton MS Julius A VII (n.d.).

- McDonald (2019) p. ix tab. 1; Flanagan (2010) p. 195 n. 123; McDonald (2007b) pp. 27 tab. 1, 71–72; McNamee (2005).

- McDonald (2007b) pp. 71–72.

- McDonald (2019) p. ix tab. 1; McDonald (2007b) pp. 27 tab. 1.

- McDonald (2019) pp. 24, 66, 77; Beuermann (2014) p. 87; Oram (2011) pp. 156, 169; Flanagan (2010) p. 195 n. 123; McDonald (2007b) pp. 70–71, 94, 170; Duffy (2004); Broderick (2003); Oram (2000) p. 105; Anderson (1922) pp. 313–314; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 78–79.

- Oram (2013) ch. 4; Oram (2011) p. 156; McDonald (2007b) p. 94.

- McDonald (2019) pp. 24, 46, 48, 66, 77; Oram (2011) pp. 156, 169; Flanagan (2010) p. 195 n. 123; McDonald (2007b) pp. 70–71; Duffy (2004); Oram (2000) pp. 105, 124; McDonald (1997) p. 85; Williams (1997) p. 260; Anderson (1922) pp. 313–314; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 78–79.

- McDonald (2007b) p. 73.

- McDonald (2012) p. 167.

- Caldwell; Hall; Wilkinson (2009) p. 156 fig. 1g.

- Caldwell; Hall; Wilkinson (2009) pp. 197–198.

- Caldwell; Hall; Wilkinson (2009) pp. 165, 197–198.

- Caldwell; Hall; Wilkinson (2009) pp. 155, 168–173.

- McDonald (2012) pp. 154, 167; McDonald (2007b) pp. 44, 77; Barrow (2006) p. 145; Oram (2000) p. 125; McDonald (1997) pp. 85, 151; Anderson (1922) p. 456; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 82–83.

- McDonald (2007b) p. 44 n. 8; McDonald (1997) p. 151 n. 86.

- McDonald (2019) p. 66; Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 36; Oram (2013) ch. 4; McDonald (2012) pp. 154–155, 167; Oram (2011) p. 169; McDonald (2008) p. 145, 145 n. 74; McDonald (2007b) pp. 78, 152; Woolf (2007) pp. 80–81; Barrow (2006) p. 145; Pollock (2005) p. 18 n. 76; Oram (2000) p. 125; McDonald (1997) p. 85; Duffy (1993) p. 64; Anderson (1922) p. 457; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 82–85.

- McDonald (2019) p. 66; McDonald (2012) p. 176 n. 73; McDonald (2008) p. 145, 145 n. 74; McDonald (2007b) pp. 78, 152; Woolf (2007) p. 80; Oram (2000) p. 125; Stringer, KJ (1998) p. 95.

- McDonald (2007b) pp. 78, 152; Woolf (2007) pp. 80–81; Oram (2000) p. 125; McDonald (1997) p. 85; Anderson (1922) p. 457; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 84–85.

- Caldwell; Hall; Wilkinson (2009) pp. 161 fig. 6g, 185 fig. 12.

- Strickland (2012) p. 113.

- Beuermann (2011) p. 125; McDonald (2008) pp. 142–144; McDonald (2007b) pp. 133–137; Johnsen (1969) p. 33.

- McDonald (2012) p. 163; McDonald (2007b) p. 133; Power (2005) p. 38; Oram (2000) p. 115; Argyll: An Inventory of the Monuments (1982) p. 143 § 4; Storm (1977) p. 123 § iv; Anderson (1922) pp. 378, 381–382; Vigfusson (1878) pp. 366–367; Flateyjarbok (1868) p. 523.

- Michaelsson (2015) p. 30 ch. 17; Oram (2013) ch. 4; Beuermann (2012) p. 1; McDonald (2012) p. 163; McDonald (2008) pp. 142–143; McDonald (2007b) p. 133; Oram (2005) p. 8; Power (2005) p. 38; Beuermann (2002) p. 420 n. 6; Oram (2000) p. 115; Argyll: An Inventory of the Monuments (1982) p. 143 § 4; Anderson (1922) pp. 378–381, 379 n. 2; Jónsson (1916) p. 468 ch. 18; Fornmanna Sögur (1835) pp. 192–195.

- Crawford (2014) pp. 72–73; McDonald (2012) p. 163; Oram (2011) p. 169; Beuermann (2011) p. 125; Beuermann (2010) pp. 106–107, 106 n. 19; McDonald (2008) pp. 142–143; McDonald (2007b) p. 134; Brown, M (2004) p. 74; Beuermann (2002) p. 420 n. 6; Oram (2000) p. 115; Williams (1997) pp. 114–115; Johnsen (1969) p. 23, 23 n. 3; Anderson (1922) p. 381, 381 nn. 1–2; Fornmanna Sögur (1835) pp. 194–195.

- Jónsson (1916) p. 472 ch. 2; AM 47 Fol (n.d.).

- Crawford (2014) pp. 72–73; Crawford (2013) § 6.6.1; McDonald (2012) p. 163; Beuermann (2011) p. 125; Beuermann (2010) pp. 106–107, 106 n. 20; McDonald (2008) p. 143; McDonald (2007b) p. 134; Brown, M (2004) p. 74; Duffy (2004); Oram (2000) p. 115; Johnsen (1969) p. 23.

- McDonald (2012) p. 180 n. 140; McDonald (2008) p. 143 n. 63; McDonald (2007b) p. 134 n. 61; Power (2005) p. 39.

- Power (2005) p. 39.

- Valante (2010); McDonald (2007b) p. 13.

- Beuermann (2011) p. 125; Beuermann (2010) p. 106; McDonald (2008) pp. 142–144; McDonald (2007b) pp. 133–137.

- Beuermann (2010) p. 106.

- McDonald (2007b) p. 135.

- Beuermann (2011) p. 125.

- Crawford (2014) pp. 72–73; Beuermann (2012) p. 8; Beuermann (2011) p. 125; McDonald (2008) pp. 142–143; McDonald (2007b) pp. 133–134; Oram (2005) p. 8; Williams (1997) pp. 114–115; Anderson (1922) pp. 380–381; Fornmanna Sögur (1835) pp. 192–195.

- Oram (2013) ch. 4; Oram (2011) p. 169.

- Williams (1997) p. 115.

- McDonald (2012) p. 163; McDonald (2008) p. 143; McDonald (2007b) p. 134.

- Caldwell; Hall; Wilkinson (2009) p. 157 fig. 2a, 163 fig. 8d, 187 fig. 14.

- McDonald (2019) pp. 61, 63, 66; McDonald (2016) pp. 339, 342; Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 36; Oram (2013) ch. 4; McDonald (2007b) pp. 78–79, 116, 152, 190; Woolf (2007) p. 81; Murray (2005) p. 290 n. 23; Pollock (2005) p. 27, 27 n. 138; Brown, M (2004) pp. 76–78; Duffy (2004); Woolf (2003) p. 178; Oram (2000) p. 125; Sellar (1997–1998); McDonald (1997) p. 85; Anderson (1922) pp. 457–458; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 84–87.

- Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 36; McDonald (2007b) p. 152.

- McDonald (2019) pp. 61, 66; McDonald (2016) p. 339; Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 36; Oram (2013) ch. 4; McDonald (2007b) pp. 79, 152–153, 190; Woolf (2007) p. 81; Barrow (2006) p. 145; Murray (2005) p. 290 n. 23; Brown, M (2004) p. 78; Woolf (2003) p. 178; Grant (2000) p. 123; Stringer, KJ (2000) p. 162 n. 142; Oram (2000) p. 125; Sellar (1997–1998); McDonald (1997) p. 85; Anderson (1922) p. 458; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 86–87.

- McDonald (2019) p. 66.

- Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 36; Oram (2013) ch. 4; McDonald (2007b) pp. 117, 152; Woolf (2007) p. 81.

- McDonald (2019) pp. 60–61; Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 36; Oram (2013) ch. 4; Oram (2011) p. 189; McDonald (2007b) pp. 117 n. 68, 152; Woolf (2007) p. 81; Pollock (2005) pp. 4, 27, 27 n. 138; Raven (2005) p. 57; Woolf (2004) p. 107; Woolf (2003) p. 178; Oram (2000) p. 125.

- McDonald (2007b) p. 117; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 219 § 3; MacDonald; MacDonald (1896) pp. 565–565; Paul (1882) pp. 670 § 3136, 678 § 3170; Document 3/30/1 (n.d.); Document 3/32/1 (n.d.); Document 3/32/2 (n.d.).

- Woolf (2007) p. 82.

- MacInnes (2019) pp. 134–135; Neville (2016) pp. 10, 19; Oram (2013) ch. 4; Strickland (2012) p. 107; Oram (2011) pp. 185–186; Ross, A (2007) p. 40; Murray (2005) pp. 290–292; Oram (2005) p. 36; Brown, M (2004) p. 75; Stringer, K (2004); Ross, AD (2003) p. 203; Oram (2000) pp. 122, 125, 130; Sellar (2000) p. 201; Stringer, KJ (1998) p. 95; McDonald (1997) pp. 83–84; Duncan (1996) p. 528; Cowan (1990) p. 114; Dunbar; Duncan (1971) p. 2; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 199.

- Oram (2013)] ch. 4; Oram (2011) p. 186; Murray (2005) pp. 290–291; Brown, M (2004) p. 75; Woolf (2004) p. 107; Sellar (2000) p. 201; McDonald (1997) p. 84; Cowan (1990) p. 114; Dunbar; Duncan (1971) p. 2; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) pp. 199–200.

- Oram (2013) ch. 4; Oram (2011) p. 189; Oram (2000) p. 125.

- McDonald (2019) pp. 60–61.

- McDonald (2019) pp. 76–77, 93.

- McDonald (2007b) pp. 79, 163; Anderson (1922) p. 458; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 86–87; Cotton MS Julius A VII (n.d.).

- McDonald (2007b) p. 163.

- McDonald (2019) pp. viii, 14, 47, 61–62, 67, 76, 93; Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 36; Oram (2013) ch. 4; McDonald (2012) p. 155; McDonald (2007b) pp. 79–80, 93; Woolf (2007) p. 81; Barrow (2006) p. 145; Power (2005) p. 43; Oram (2000) p. 125; Sellar (1997–1998); McDonald (1997) p. 85; Williams (1997) p. 258; Matheson (1978–1980); Anderson (1922) p. 458; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 86–87.

- McDonald (2007b) pp. 93–94; Woolf (2007) p. 81; Oram (2000) p. 125.

- McDonald (2007b) p. 94.

- McDonald (2019) p. 67; Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 36; Thomas (2014) p. 259; Veach (2014) p. 200; Oram (2013) ch. 4; McDonald (2012) p. 155; McDonald (2007b) pp. 80, 93; Woolf (2007) p. 81; Barrow (2006) p. 145; Power (2005) p. 43; Broderick (2003); Grant (2000) p. 123; Oram (2000) p. 125; Sellar (1997–1998); McDonald (1997) p. 85; Williams (1997) p. 258, 258 n. 99; Gade (1994) pp. 199, 201, 203; Anderson (1922) pp. 458–459; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 86–89.

- McDonald (2019) p. 67; McDonald (2012) p. 155; McDonald (2007b) p. 93; Barrow (2006) p. 144; Broderick (2003); Sellar (1997–1998); Williams (1997) p. 261; Anderson (1922) pp. 458–459; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 86–89.

- Barrow (2006) p. 144; Sellar (1997–1998).

- Williams (1997) p. 261.

- McDonald (2019) pp. 47, 67; McDonald (2012) p. 155; McDonald (2007b) pp. 79, 93; Sellar (1997–1998); Anderson (1922) p. 458; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 86–87.

- McDonald (2019) p. 67; Thomas (2014) p. 259; McDonald (2012) p. 155; McDonald (2007b) p. 80; Barrow (2006) p. 145; Sellar (1997–1998); Anderson (1922) p. 459; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 88–89.

- McDonald (2019) p. 67; McDonald (2012) p. 155; McDonald (2007b) p. 80; Sellar (1997–1998).

- McDonald (2019) pp. 67, 82 n. 42; Thomas (2014) p. 259; Barrow (2006) p. 145, 145 n. 24; Sellar (1997–1998); MacLeod (2002) p. 13.

- McDonald (2019) p. 67; Barrow (2006) p. 145 n. 24; Donaldson (1923) p. 170; Forbes (1923) p. 244; Skye, Eilean Chaluim Chille (n.d.).

- Sellar (1997–1998); The Royal Commission on Ancient (1928) pp. 165–166 § 535.

- Thomas (2014) p. 259; Anderson (1922) p. 459; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 88–89.

- Sellar (1997–1998); Matheson (1978–1980); Sinclair (1795) p. 538.

- Sellar (1997–1998); Matheson (1978–1980).

- Donaldson (1923) pp. 171–172; Forbes (1923) p. 244.

- McDonald (2019) pp. 67, 82 n. 42; Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 36; McDonald (2007b) p. 80, 80 n. 55; Power (2005) pp. 32, 43; Sellar (1997–1998); Williams (1997) p. 258.

- McDonald (2019) pp. 67, 82 n. 42; McDonald (2007b) p. 80, 80 n. 55; Sellar (1997–1998).

- Cochran-Yu (2015) pp. 36–38; Munro; Munro (2008); Grant (2000) p. 123; McDonald (1997) p. 85.

- Cochran-Yu (2015) pp. 36–37.

- McDonald (2019) p. 67; Oram (2013) ch. 4; McDonald (2007b) p. 80; Power (2005) p. 43; Sellar (1997–1998); Williams (1997) p. 258, 258 n. 99; Gade (1994) p. 201; Anderson (1922) p. 459; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 88–89.

- McDonald (2019) p. 67; McDonald (2007b) p. 80; Sellar (1997–1998); Gade (1994) pp. 199, 201; Storm (1977) pp. 24 § i, 63 § iii, 126 § iv, 185 § v, 326 § viii, 479 § x; Anderson (1922) pp. 454–455; Vigfusson (1878) p. 369; Flateyjarbok (1868) p. 526.

- Sellar; Maclean (1999) p. 11; Sellar (1997–1998); Macphail (1914) pp. 7–8.

- McDonald (2019) p. 73; McDonald (2007b) pp. 96–98; Gillingham (2004).

- McDonald (2019) p. 73; Thorpe (1978) p. 261 bk. 2 ch. 4; The Itinerary Through Wales (1908) p. 193 bk. 2 ch. 4; Dimock (1868) pp. 211–212 bk. 2 ch. 3.

- McDonald (2007b) p. 96.

- McDonald (2007b) p. 96.

- McDonald (2019) pp. 72–73; McDonald (2007b) p. 91.

- Gade (1994) pp. 199–200.

- Oram (2013) ch. 4.

- McDonald (2019) p. 67; McDonald (2012) p. 155.

- Stevenson (1914) pp. 16–17 pl. 1 fig. 6, 17, 17 n. 7.

- McDonald (2019) pp. 47, 67; Veach (2014) p. 200; Oram (2013) ch. 4; Oram (2011) p. 189; McDonald (2007a) p. 63; McDonald (2007b) pp. 52–53, 80, 153, 212; Brown, M (2004) p. 78; Oram (2000) p. 126; Duffy (1993) p. 105; Anderson (1922) p. 459; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 88–89.

- Brown, D (2016) p. 148; Veach (2014) p. 201; Beuermann (2010) p. 111, 111 n. 39; Power (2005) p. 44; McDonald (2004) p. 195; McDonald (1997) pp. 88–89; Williams (1997) p. 117, 117 n. 142; Gade (1994) pp. 202–203; Cowan (1990) p. 114; Anderson (1922) p. 455; Jónsson (1916) p. 522 ch. 98; Kjær (1910) p. 390 ch. 106/101; Dasent (1894) pp. 89–90 ch. 101; Vigfusson (1887) p. 87 ch. 101; Unger (1871) p. 440 ch. 105; Flateyjarbok (1868) p. 61 ch. 84; Regesta Norvegica (n.d.) vol. 1 p. 168 § 501.

- McDonald (1997) p. 89; Williams (1997) p. 117; Gade (1994) p. 203; Regesta Norvegica (n.d.) vol. 1 p. 168 § 501 n. 1.

- Williams (1997) p. 117; Regesta Norvegica (n.d.) vol. 1 p. 168 § 501 n. 1.

- Oram (2011) pp. 189–190; McDonald (2007b) pp. 80–81, 153, 155–156; McNamee (2005); Brown, M (2004) p. 78; Oram (2000) p. 126.

- Stringer, KJ (1998) p. 83.

- Oram (2013) ch. 4; McNamee (2005); Oram (2000) pp. 125–126; Duffy (1993) p. 105; Oram (1988) pp. 136–137; Bain (1881) pp. 158–159 § 890; Sweetman (1875) pp. 185–186 § 1218.

- McDonald (2019) pp. 47–48; Oram (2013) ch. 4; Oram (2011) p. 189; McDonald (2007b) pp. 81, 155; Oram (2000) p. 126; McDonald (1997) p. 86; Duffy (1993) p. 105; Oram (1988) p. 137; Anderson (1922) p. 459; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 88–89.

- McDonald (2007a) p. 59; McDonald (2007b) pp. 128–129 pl. 1; Rixson (1982) pp. 114–115 pl. 1; Cubbon (1952) p. 70 fig. 24; Kermode (1915–1916) p. 57 fig. 9.

- McDonald (2012) p. 151; McDonald (2007a) pp. 58–59; McDonald (2007b) pp. 54–55, 128–129 pl. 1; Wilson (1973) p. 15.

- McDonald (2016) p. 337; McDonald (2012) p. 151; McDonald (2007b) pp. 120, 128–129 pl. 1.

- McDonald (2019) pp. 24–25, 46, 48, 62; Brown, D (2016) p. 192 n. 190; Oram (2013) ch. 4; Oram (2011) pp. 189–190; McDonald (2007a) pp. 64–65 n. 87; McDonald (2007b) pp. 81, 155; Brown, M (2004) p. 78; Oram (2000) p. 126; Duffy (1993) p. 105; Oram (1988) p. 137; Anderson (1922) pp. 459–460; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 88–91.

- Oram (2013) ch. 4; McDonald (2007b) p. 155; McNamee (2005); Brown, M (2004) p. 78; Oram (2000) p. 126; Stringer, KJ (1998) p. 96; McDonald (1997) p. 92.

- McDonald (2007b) p. 155.

- Oram (2000) p. 126.

- Oram (2000) pp. 126, 139 n. 107.

- Broderick (2003).

- Fee (2012) p. 129; McDonald (2007b) p. 82.

- Crawford (2014) pp. 74–75.

- Insley; Wilson (2006).

- Insley; Wilson (2006); O'Grady (2008) p. 58; Anderson (1922) p. 508; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 94–95.

- McDonald (2019) p. 67; McDonald (2007b) p. 81; Duffy (1993) p. 106.

- Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 38; Oram (2013) ch. 4; Oram (2011) p. 190; McDonald (2007b) pp. 81, 155–156; Brown, M (2004) p. 78; Duffy (2004); Oram (2004); Oram (2000) p. 127; Stringer, KJ (1998) p. 95; Duffy (1993) p. 106; Oram (1988) p. 137; Anderson (1922) p. 465; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 90–91.

- McDonald (2007b) p. 149; Oram (2000) p. 127; Stringer, KJ (1998) p. 95; Duffy (1993) p. 105; Oram (1988) p. 137; Simpson; Galbraith (n.d.) p. 136 § 9; Document 1/16/1 (n.d.).

- Oram (2013) ch. 4; McDonald (2007b) pp. 81, 156; Anderson (1922) pp. 465–466; Munch; Goss (1874a) pp. 90–91.

- McDonald (2019) pp. 67–68; Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 38; Oram (2013) ch. 4; Oram (2011) p. 190; McDonald (2007a) p. 63; McDonald (2007b) pp. 70, 81; Harrison (2002) p. 16; Oram (2000) pp. 127–128; Oram (1988) p. 137; Anderson (1922) p. 466; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 90–91.

- McDonald (2019) pp. 24, 68; Oram (2013) ch. 4; Oram (2011) p. 190; McDonald (2007b) p. 82; Brown, M (2004) p. 78; Oram (2000) pp. 127–128; Williams (1997) p. 258; Oram (1988) p. 137; Anderson (1922) p. 466; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 92–93.

- McDonald (2007b) p. 29; Storm (1977) pp. 128 § iv, 480 § x; Anderson (1922) p. 467; Vigfusson (1878) p. 371; Flateyjarbok (1868) p. 527.

- McDonald (2019) p. 68; McDonald (2007b) p. 82, 82 n. 72; McLeod (2002) p. 28 n. 12; Anderson (1922) p. 467; Stevenson (1839) p. 40.

- Williams (1997) p. 258.

- Munch; Goss (1874) p. 92; Cotton MS Julius A VII (n.d.).

- Ó Cróinín (2017) p. 258; McDonald (2016) p. 338; McDonald (2007b) p. 86; Power (2005) p. 47; Fellows-Jensen (1998) p. 30; Sellar (1997–1998); Sawyer (1982) p. 111; Megaw (1976) p. 16; Anderson (1922) p. 472 n. 5.

- Oram (2011) p. 192; McDonald (1997) p. 89; Oram (2000) p. 128; Cowan (1990) p. 114; Oram (1988) p. 138; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 201.

- McDonald (2019) p. 68; Oram (2013) ch. 4; Power (2005) p. 44; Stringer, KJ (1998) p. 97; McDonald (1997) p. 88; Oram (1988) p. 138; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 200; Anderson (1922) p. 464, 464 n. 4; Jónsson (1916) p. 555 ch. 164; Kjær (1910) p. 461 ch. 177/162; Dasent (1894) p. 150 ch. 162; Vigfusson (1887) p. 144 ch. 162; Unger (1871) p. 475 ch. 168; Flateyjarbok (1868) p. 100 ch. 135.

- Oram (2013) ch. 4; Strickland (2012) p. 104; Carpenter (2003) ch. 10 ¶ 63; Oram (2000) p. 128; Oram (1988) p. 138; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 201; Anderson (1922) p. 464, 464 n. 4; Jónsson (1916) p. 555 ch. 165; Kjær (1910) p. 462 ch. 178/163; Dasent (1894) p. 150 ch. 163; Vigfusson (1887) p. 144 ch. 163; Unger (1871) pp. 475–476 ch. 169; Flateyjarbok (1868) p. 100 ch. 136.

- Oram (2013) ch. 4; Power (2005) p. 44; Brown, M (2004) p. 78; McDonald (1997) p. 89; Cowan (1990) p. 114; Johnsen (1969) p. 26; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) pp. 200–202; Anderson (1922) pp. 464–465; Jónsson (1916) p. 555 ch. 165; Kjær (1910) p. 462 ch. 178/163; Dasent (1894) p. 150 ch. 163; Vigfusson (1887) p. 144 ch. 163; Unger (1871) p. 476 ch. 169; Flateyjarbok (1868) p. 100 ch. 136.

- Oram (2013) ch. 4; Oram (2011) p. 192; McNamee (2005); Power (2005) p. 44; Oram (2000) p. 128; McDonald (1997) p. 89; Oram (1988) p. 138.

- Jónsson (1916) p. 557 ch. 169; AM 47 Fol (n.d.).

- McDonald (2019) p. 68; McDonald (2007b) p. 86; McDonald (1997) pp. 89–90; Storm (1977) pp. 24 § i, 64 § iii, 128 § iv, 187 § v, 327 § viii; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 201; Anderson (1922) pp. 471–473; Jónsson (1916) p. 556 ch. 167; Kjær (1910) p. 463 ch. 180/165; Dasent (1894) p. 151 ch. 164; Vigfusson (1887) p. 145 ch. 165; Vigfusson (1878) p. 371; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 92–93; Unger (1871) p. 476 ch. 171; Flateyjarbok (1868) pp. 101 ch. 137, 527; Stevenson (1839) p. 41.

- Oram (2013) ch. 4; Beuermann (2010) p. 107 n. 25; Power (2005) p. 44.

- Oram (2013) ch. 4; McNamee (2005).

- Downham (2008); McDonald (2007b) pp. 86–87.

- McDonald (2007b) p. 86.

- McDonald (2019) p. 68; McDonald (2016) p. 338; McDonald (2007b) p. 86; Duffy (2002) p. 191 n. 18; Sellar (1997–1998); Megaw (1976) p. 16; Anderson (1922) p. 472, 472 n. 5; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 92–93.

- Ó Cróinín (2017) p. 258; McDonald (2016) p. 339; Fellows-Jensen (1998) p. 30; Sawyer (1982) p. 111; Megaw (1976) p. 16.

- McDonald (2016) p. 339; Duffy (2002) p. 191 n. 18; Fellows-Jensen (1998) p. 30; Sawyer (1982) p. 111.

- McDonald (2019) p. 82 n. 50; McDonald (2007b) p. 86 n. 93; Sellar (1997–1998); Megaw (1976) pp. 16–17; Anderson (1922) pp. 472 n. 5, 478; Dasent (1894) p. 154 ch. 167; Vigfusson (1887) p. 148 ch. 167.

- McDonald (2019) p. 82 n. 50; McDonald (2007b) p. 86 n. 93; Megaw (1976) pp. 16–17.

- Megaw (1976) pp. 16–17.

- Oram (2000) p. 128; McDonald (1997) pp. 89–90; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) pp. 200–201; Anderson (1922) pp. 473–474; Jónsson (1916) p. 556 ch. 167; Kjær (1910) p. 463 ch. 180/165; Dasent (1894) p. 151 ch. 164; Vigfusson (1887) p. 145 ch. 165; Unger (1871) p. 476 ch. 171; Flateyjarbok (1868) p. 101 ch. 137.

- Murray (2005) p. 293; Oram (2005) p. 40; Oram (2000) p. 128; Williams (1997) p. 117; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 201; Anderson (1922) p. 474, 474 n. 2, 474 n. 9; Jónsson (1916) p. 556 ch. 168; Kjær (1910) p. 464 ch. 181/166; Dasent (1894) p. 152 ch. 166; Vigfusson (1887) p. 146 ch. 166; Unger (1871) p. 477 ch. 172; Flateyjarbok (1868) p. 101 ch. 138.

- Anderson (1922) p. 474, 474 n. 2; Jónsson (1916) p. 556 ch. 168; Kjær (1910) p. 464 ch. 181/166; Dasent (1894) p. 152 ch. 166; Vigfusson (1887) p. 146 ch. 166; Unger (1871) p. 477 ch. 172; Flateyjarbok (1868) p. 101 ch. 138.

- Anderson (1922) p. 474, 474 n. 9; Jónsson (1916) p. 556 ch. 168; Kjær (1910) p. 464 ch. 181/166; Dasent (1894) p. 152 ch. 166; Vigfusson (1887) p. 146 ch. 166; Unger (1871) p. 477 ch. 172; Flateyjarbok (1868) p. 101 ch. 138.

- Schach (2016); Power (2005) p. 13 n. 9.

- Power (2005) p. 13 n. 9.

- Oram (2013) ch. 4; Anderson (1922) pp. 474–475, 475 n. 1, 475 n. 3; Jónsson (1916) pp. 556–557 ch. 168; Kjær (1910) p. 464 ch. 181/166; Dasent (1894) p. 152 ch. 166; Vigfusson (1887) p. 146 ch. 166; Unger (1871) p. 477 ch. 172; Flateyjarbok (1868) pp. 101–102 ch. 138.

- Murray (2005) p. 293; McDonald (1997) p. 90; Cowan (1990) pp. 114–115; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 201; Anderson (1922) p. 475; Jónsson (1916) p. 557 ch. 169; Kjær (1910) p. 465 ch. 182/167; Dasent (1894) pp. 152–153 ch. 167; Vigfusson (1887) pp. 146–147 ch. 167; Unger (1871) p. 477 ch. 173; Flateyjarbok (1868) p. 102 ch. 138.

- Stell (2000) p. 277; Pringle (1998) p. 152; Anderson (1922) p. 476, 476 n. 5; Jónsson (1916) p. 557 ch. 169; Kjær (1910) p. 465 ch. 182/167; Dasent (1894) p. 153 ch. 167; Vigfusson (1887) p. 147 ch. 167; Unger (1871) p. 477 ch. 173; Flateyjarbok (1868) p. 102 ch. 138.

- Stell (2000) p. 278; McGrail (1995) p. 41.

- Oram (2013) ch. 4; Oram (2011) p. 192; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 250; Brown, M (2004) p. 78; Oram (2000) p. 129; Stringer, KJ (1998) p. 97; Registrum Monasterii de Passelet (1832) pp. 47–48; Document 1/7/164 (1832).

- Oram (2013) ch. 4; Oram (2011) p. 192; Boardman (2007) p. 95; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) pp. 251–252; Tabraham (2005) p. 26; Brown, M (2004) p. 78; Oram (2000) p. 129; Pringle (1998) p. 152; McDonald (1997) pp. 90, 243; McGrail (1995) pp. 39–42; Cowan (1990) p. 115; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 201.

- Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 252 n. 34; Pringle (1998) p. 152; Anderson (1922) p. 476 n. 8; Kjær (1910) p. 466 ch. 182/167; Dasent (1894) p. 153 ch. 167; Vigfusson (1887) p. 147 ch. 167; Unger (1871) p. 477 ch. 173; Flateyjarbok (1868) p. 102 ch. 138.

- Stell (2000) p. 277; Anderson (1922) p. 476 n. 9; Kjær (1910) p. 466 ch. 182/167; Dasent (1894) p. 153 ch. 167; Vigfusson (1887) p. 147 ch. 167; Unger (1871) pp. 477–478 ch. 173; Flateyjarbok (1868) p. 102 ch. 138.

- McDonald (2007b) p. 158; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 251; Pringle (1998) p. 152; McGrail (1995) p. 39; Anderson (1922) p. 476; Jónsson (1916) p. 557 ch. 169; Kjær (1910) p. 465 ch. 182/167; Dasent (1894) p. 153 ch. 167; Vigfusson (1887) p. 147 ch. 167; Unger (1871) p. 477 ch. 173; Flateyjarbok (1868) p. 102 ch. 138.

- Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 251.

- Oram (2011) p. 192; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 252; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 201; Anderson (1922) p. 476, 476 n. 12; Jónsson (1916) p. 557 ch. 169; Kjær (1910) p. 466 ch. 182/167; Dasent (1894) p. 153 ch. 167; Vigfusson (1887) p. 147 ch. 167; Unger (1871) p. 478 ch. 173; Flateyjarbok (1868) p. 102 ch. 138.

- McDonald (2007a) pp. 71–72; McDonald (2007b) p. 156; Stringer, KJ (1998) p. 84; McDonald (1997) p. 92; Anderson (1922) p. 476, 476 n. 12; Jónsson (1916) p. 557 ch. 169; Kjær (1910) p. 466 ch. 182/167; Dasent (1894) p. 153 ch. 167; Vigfusson (1887) p. 147 ch. 167; Unger (1871) p. 478 ch. 173; Flateyjarbok (1868) p. 102 ch. 138.

- McDonald (2007a) pp. 71–72; McDonald (2007b) p. 156; Stringer, KJ (1998) p. 84; McDonald (1997) p. 92.

- McDonald (2007a) pp. 71–72; McDonald (2007b) p. 156; Smith (1998); Stringer, KJ (1998) p. 84; McDonald (1997) p. 92.

- Imsen (2010) p. 13 n. 2; Lewis (1987) p. 456; Tremlett; London; Wagner (1967) p. 72.

- Lewis (1987) p. 456; Tremlett; London; Wagner (1967) p. 72.

- Imsen (2010) pp. 13–14, 13 n. 2.

- Oram (2013) ch. 4; Oram (2011) p. 192; McDonald (2007b) p. 158; Power (2005) p. 45; Oram (2000) p. 129; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 201; Anderson (1922) pp. 476–477; Jónsson (1916) p. 557 ch. 169; Kjær (1910) p. 466 ch. 182/167; Dasent (1894) p. 153 ch. 167; Vigfusson (1887) p. 148 ch. 167; Unger (1871) p. 478 ch. 173; Flateyjarbok (1868) p. 102 ch. 138.

- Oram (2013) ch. 4; McDonald (2007b) p. 158; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 252; Oram (2000) p. 129; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 201.

- Oram (2013) ch. 4; McDonald (2007b) p. 158; Anderson (1922) p. 477; Jónsson (1916) p. 557 ch. 169; Kjær (1910) p. 466 ch. 182/167; Dasent (1894) p. 153 ch. 167; Vigfusson (1887) p. 148 ch. 167; Unger (1871) p. 478 ch. 173; Flateyjarbok (1868) p. 102 ch. 138.

- McDonald (2019) pp. 69, 75; Oram (2013) ch. 4; Oram (2011) p. 192; McDonald (2007b) pp. 87, 92, 158–159; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 252; Oram (2000) p. 129; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 201; Anderson (1922) pp. 471–472, 477; Jónsson (1916) pp. 557–558 ch. 169; Kjær (1910) p. 466 ch. 182/167; Dasent (1894) pp. 153–154 ch. 167; Vigfusson (1887) p. 148 ch. 167; Unger (1871) p. 478 ch. 173; Flateyjarbok (1868) pp. 102–103 ch. 138; Stevenson (1839) p. 41.

- Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 38.

- Murray (2005) p. 295, 295 n. 47; McDonald (1997) p. 91; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 201.

- Duncan (1996) p. 548; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 201.

- McDonald (2019) p. 69; McDonald (2007b) p. 87; Oram (2000) p. 128; Williams (1997) p. 151; Oram (1988) p. 139.

- Oram (2000) p. 128; Oram (1988) p. 139.

- Beuermann (2010) p. 107 n. 25.

- Oram (1988) p. 139.

- McDonald (2019) p. 69; Oram (2013) ch. 4; McDonald (2007b) pp. 87, 92; Power (2005) pp. 45–46; Sellar (1997–1998); Williams (1997) p. 117; Gade (1994) p. 201; Oram (1988) p. 140; Matheson (1978–1980); Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 202; Anderson (1922) pp. 472, 478; Jónsson (1916) p. 558 ch. 169; Kjær (1910) p. 467 ch. 182/167; Dasent (1894) p. 154 ch. 167; Vigfusson (1887) p. 148 ch. 167; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 92–95; Unger (1871) p. 478 ch. 173; Flateyjarbok (1868) p. 103 ch. 138.

- McDonald (2012) p. 152.

- McDonald (2007b) p. 158; Carpenter (2003) ch. 10 ¶ 64; McDonald (1997) p. 90; Anderson (1922) p. 478; Jónsson (1916) p. 558 ch. 169; Kjær (1910) p. 467 ch. 182/167; Dasent (1894) p. 154 ch. 167; Vigfusson (1887) p. 148 ch. 167; Unger (1871) p. 478 ch. 173; Flateyjarbok (1868) p. 103 ch. 138.

- McDonald (2007b) p. 159.

- McDonald (2019) p. 69; McDonald (2007b) pp. 87, 159; McNamee (2005); Williams (1997) pp. 117–118; Duffy (1993) p. 106.

- Oram (2013) ch. 4; Anderson (1922) pp. 471–472; Stevenson (1839) p. 41.

- Oram (2013) ch. 4; Oram (2000) p. 131; Anderson (1922) p. 478; Luard (1866) p. 126.

- Oram (2013) ch. 4; McDonald (2007b) p. 87.

- McDonald (2019) p. 69; McDonald (2007b) p. 87; Anderson (1922) p. 474, 474 n. 8; Jónsson (1916) p. 556 ch. 168; Kjær (1910) p. 464 ch. 181/166; Dasent (1894) p. 152 ch. 166; Vigfusson (1887) p. 146 ch. 166; Flateyjarbok (1868) p. 101 ch. 138.

- McDonald (2007b) p. 87; Barrow (2006) pp. 145–146.

- Beuermann (2010) p. 107; McDonald (2007b) p. 87; McNamee (2005); Williams (1997) p. 118; Johnsen (1969) p. 26.

- McDonald (2007b) p. 88; McNamee (2005).

- McDonald (2007b) p. 88.

- McDonald (2007b) pp. 88–89.

- McDonald (2007b) pp. 86, 89–90.

References

Primary sources

- "AM 47 Fol (E) – Eirspennill". Skaldic Project. n.d. Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- Anderson, AO, ed. (1922). Early Sources of Scottish History, A.D. 500 to 1286. 2. London: Oliver and Boyd.

- Bain, J, ed. (1881). Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland. 1. Edinburgh: H. M. General Register House. hdl:2027/mdp.39015014807203.

- "Cotton MS Julius A VII". British Library. n.d. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- Dasent, GW, ed. (1894). Icelandic Sagas and Other Historical Documents Relating to the Settlements and Descents of the Northmen on the British Isles. Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores. 4. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office.

- Dimock, JF, ed. (1868). Giraldi Cambrensis Opera. Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores. 6. London: Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer.

- "Document 1/16/1". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371. n.d. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- "Document 1/7/164". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371. n.d. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- "Document 3/30/1". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371. n.d. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- "Document 3/32/1". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371. n.d. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- "Document 3/32/2". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371. n.d. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- Flateyjarbok: En Samling af Norske Konge-Sagaer med Indskudte Mindre Fortællinger om Begivenheder i og Udenfor Norse Same Annaler. 3. Oslo: P.T. Mallings Forlagsboghandel. 1868. OL 23388689M.

- Fornmanna Sögur. 9. Copenhagen: S. L. Möllers. 1835.

- Jónsson, F, ed. (1916). Eirspennill: Am 47 Fol. Oslo: Julius Thømtes Boktrykkeri. OL 18620939M.

- Kjær, A, ed. (1910). Det Arnamagnæanske Hanndskrift 81a Fol. (Skálholtsbók Yngsta). Oslo: Mallingske Bogtrykkeri. OL 25104944M.

- Luard, HR, ed. (1866). Annales Monastici. Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores. 3. London: Longman's Green, Reader, and Dyer.

- MacDonald, A; MacDonald, A (1896). The Clan Donald. 1. Inverness: The Northern Counties Publishing Company.

- Macphail, JRN, ed. (1914). Highland Papers. Publications of the Scottish History Society. 1. Edinburgh: Scottish History Society. OL 23303390M.

- Michaelsson, E (2015). Böglunga Saga (Styttri Gerð) (MA thesis). Háskóli Íslands. hdl:1946/22667.

- Munch, PA; Goss, A, eds. (1874). Chronica Regvm Manniæ et Insvlarvm: The Chronicle of Man and the Sudreys. 1. Douglas, IM: Manx Society.

- Paul, JB, ed. (1882). Registrum Magni Sigilli Regum Scotorum: The Register of the Great Seal of Scotland, A.D. 1424–1513. Edinburgh: H.M. General Register House. OL 23329160M.

- "Regesta Norvegica". Dokumentasjonsprosjektet. n.d. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- Registrum Monasterii de Passelet, Cartas Privilegia Conventiones Aliaque Munimenta Complectens, A Domo Fundata A.D. MCLXIII Usque Ad A.D. MDXXIX. Edinburgh. 1832. OL 24829867M.

- Simpson, GG; Galbraith, JD, eds. (n.d.). Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland. 5. Scottish Record Office.

- Sinclair, J, ed. (1795). The Statistical Account of Scotland. 16. Edinburgh: William Creech.

- Stevenson, J, ed. (1839). Chronicon de Lanercost, M.CC.I.–M.CCC.XLVI. Edinburgh: The Bannatyne Club. OL 7196137M.

- Storm, G, ed. (1977) [1888]. Islandske Annaler Indtil 1578. Oslo: Norsk historisk kjeldeskrift-institutt. hdl:10802/5009. ISBN 82-7061-192-1.

- Sweetman, HS, ed. (1875). Calendar of Documents Relating to Ireland, Preserved in Her Majesty's Public Record Office, London, 1171–1251. London: Longman & Co.

- The Itinerary Through Wales and the Description of Wales. Everyman's Library. London: J. M. Dent & Sons. 1908. OL 24871133M.

- Thorpe, L, ed. (1978). The Journey Through Wales and the Description of Wales. Penguin Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. OL 22125679M.

- Unger, CR, ed. (1871). Codex Frisianus: En Samling Af Norske Konge-Sagaer. Oslo: P.T. Mallings Forlagsboghandel. hdl:2027/hvd.32044084740760. OL 23385970M.

- Vigfusson, G, ed. (1878). Sturlunga Saga Including the Islendinga Saga of Lawman Sturla Thordsson and Other Works. 2. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Vigfusson, G, ed. (1887). Icelandic Sagas and Other Historical Documents Relating to the Settlements and Descents of the Northmen on the British Isles. Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores. 2. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office.

Secondary sources

- Argyll: An Inventory of the Monuments. 4. The Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland. 1982. ISBN 0-11-491728-0.

- Barrow, GWS (2006). "Skye From Somerled to A.D. 1500" (PDF). In Kruse, A; Ross, A (eds.). Barra and Skye: Two Hebridean Perspectives. Edinburgh: The Scottish Society for Northern Studies. pp. 140–154. ISBN 0-9535226-3-6.

- Beuermann, I (2002). "Metropolitan Ambitions and Politics: Kells-Mellifont and Man & the Isles". Peritia. 16: 419–434. doi:10.1484/J.Peri.3.497. eISSN 2034-6506. ISSN 0332-1592.

- Beuermann, I (2012). The Norwegian Attack on Iona in 1209–10: The Last Viking Raid?. Iona Research Conference, April 10th to 12th 2012. pp. 1–10. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- Beuermann, I (2010). "'Norgesveldet?' South of Cape Wrath? Political Views Facts, and Questions". In Imsen, S (ed.). The Norwegian Domination and the Norse World c. 1100–c. 1400. Trondheim Studies in History. Trondheim: Tapir Academic Press. pp. 99–123. ISBN 978-82-519-2563-1.

- Beuermann, I (2011). "Jarla Sǫgur Orkneyja. Status and Power of the Earls of Orkney According to Their Sagas". In Steinsland, G; Sigurðsson, JV; Rekdal, JE; Beuermann, I (eds.). Ideology and Power in the Viking and Middle Ages: Scandinavia, Iceland, Ireland, Orkney and the Faeroes. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures. Leiden: Brill. pp. 109–161. ISBN 978-90-04-20506-2. ISSN 1569-1462.

- Beuermann, I (2014). "No Soil for Saints: Why was There No Native Royal Martyr in Man and the Isles". In Sigurðsson, JV; Bolton, T (eds.). Celtic-Norse Relationships in the Irish Sea in the Middle Ages, 800–1200. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures. Leiden: Brill. pp. 81–95. ISBN 978-90-04-25512-8. ISSN 1569-1462.

- Boardman, S (2007). "The Gaelic World and the Early Stewart Court" (PDF). In Broun, D; MacGregor, M (eds.). Mìorun Mòr nan Gall, 'The Great Ill-Will of the Lowlander'? Lowland Perceptions of the Highlands, Medieval and Modern. Centre for Scottish and Celtic Studies, University of Glasgow. pp. 83–109. OCLC 540108870.

- Broderick, G (2003). "Tynwald: A Manx Cult-Site and Institution of Pre-Scandinavian Origin?". Studeyrys Manninagh. ISSN 1478-1409. Archived from the original on 7 February 2009.

- Brown, D (2016). Hugh de Lacy, First Earl of Ulster: Rising and Fall in Angevin Ireland. Irish Historical Monographs. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-78327-134-4. ISSN 1740-1097.

- Brown, M (2004). The Wars of Scotland, 1214–1371. The New Edinburgh History of Scotland. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-1238-6.

- Caldwell, DH; Hall, MA; Wilkinson, CM (2009). "The Lewis Hoard of Gaming Pieces: A Re-examination of Their Context, Meanings, Discovery and Manufacture". Medieval Archaeology. 53 (1): 155–203. doi:10.1179/007660909X12457506806243. eISSN 1745-817X. ISSN 0076-6097.

- Carpenter, D (2003). The Struggle For Mastery: Britain 1066–1284 (EPUB). The Penguin History of Britain. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-14-193514-0.

- Cochran-Yu, DK (2015). A Keystone of Contention: The Earldom of Ross, 1215–1517 (PhD thesis). University of Glasgow.

- Cowan, EJ (1990). "Norwegian Sunset – Scottish Dawn: Hakon IV and Alexander III". In Reid, NH (ed.). Scotland in the Reign of Alexander III, 1249–1286. Edinburgh: John Donald Publishers. pp. 103–131. ISBN 0-85976-218-1.

- Crawford, BE (2013). The Northern Earldoms: Orkney and Caithness From 870 to 1470. Edinburgh: Birlinn Limited. ISBN 978-0-85790-618-2.

- Crawford, BE (2014). "The Kingdom of Man and the Earldom of Orkney—Some Comparisons". In Sigurðsson, JV; Bolton, T (eds.). Celtic-Norse Relationships in the Irish Sea in the Middle Ages, 800–1200. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures. Leiden: Brill. pp. 65–80. ISBN 978-90-04-25512-8. ISSN 1569-1462.

- Cubbon, W (1952). Island Heritage: Dealing With Some Phases of Manx History. Manchester: George Falkner & Sons. OL 24831804M.

- Donaldson, MEM (1923). Wanderings in the Western Highland and Islands. Paisley: Alexander Gardner.

- Downham, C (2008). "Review of RA McDonald, Manx Kingship in its Irish Sea Setting 1187–1229: King Rognvaldr and the Crovan Dynasty". The Medieval Review. ISSN 1096-746X.

- Duffy, S (1993). Ireland and the Irish Sea Region, 1014–1318 (PhD thesis). Trinity College, Dublin. hdl:2262/77137.

- Duffy, S (2002). "The Bruce Brothers and the Irish Sea World, 1306–29". In Duffy, S (ed.). Robert the Bruce's Irish Wars: The Invasions of Ireland 1306–1329. Stroud: Tempus Publishing. pp. 45–70. ISBN 0-7524-1974-9.

- Duffy, S (2004). "Ragnvald (d. 1229)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/50617. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- Dunbar, JG; Duncan, AAM (1971). "Tarbert Castle: A Contribution to the History of Argyll". Scottish Historical Review. 50 (1): 1–17. eISSN 1750-0222. ISSN 0036-9241. JSTOR 25528888.

- Duncan, AAM (1996) [1975]. Scotland: The Making of the Kingdom. The Edinburgh History of Scotland. Edinburgh: Mercat Press. ISBN 0 901824 83 6.

- Duncan, AAM; Brown, AL (1956–1957). "Argyll and the Isles in the Earlier Middle Ages" (PDF). Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 90: 192–220. eISSN 2056-743X. ISSN 0081-1564.

- Fee, CR (2012). "Með Lögum Skal Land Vort Byggja (With Law Shall the Land be Built): Law as a Defining Characteristic of Norse Society in Saga Conflicts and Assembly Sites Throughout the Scandinavian North Atlantic". In Hudson, B (ed.). Studies in the Medieval Atlantic. The New Middle Ages. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 123–142. doi:10.1057/9781137062390_5. ISBN 978-1-137-06239-0.

- Fellows-Jensen, G (1998) [1998]. The Vikings and Their Victims: The Verdict of the Names (PDF). London: Viking Society for Northern Research. ISBN 978-0-903521-39-0.

- Flanagan, MT (2010). The Transformation of the Irish Church in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries. Studies in Celtic History. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-597-4. ISSN 0261-9865.

- Forbes, AR (1923). Place-Names of Skye and Adjacent Islands. Paisley: Alexander Gardner.

- Forte, A; Oram, RD; Pedersen, F (2005). Viking Empires. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82992-2.

- Gade, KE (1994). "1236: Órækja Meiddr ok Heill Gerr" (PDF). In Tómasson, S (ed.). Samtíðarsögur: The Contemporary Sagas. Forprent. Reykjavík: Stofnun Árna Magnússona. pp. 194–207.

- Gillingham, J (2004) [1999]. "Killing and Mutilating Political Enemies in the British Isles From the Late Twelfth to the Early Fourteenth Century: A Comparative Study". In Smith, B (ed.). Britain and Ireland 900–1300: Insular Responses to Medieval European Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 114–134. ISBN 0-511-03855-0.

- Grant, A (2000). "The Province of Ross and the Kingdom of Alba". In Cowan, EJ; McDonald, RA (eds.). Alba: Celtic Scotland in the Middle Ages. East Linton: Tuckwell Press. pp. 88–126. ISBN 1-86232-151-5.

- Harrison, A (2002). "Sources for the Documentary History of Peel Castle". In Freke, D (ed.). Excavations on St Patrick's Isle, Peel, Isle of Man 1982–88: Prehistoric, Viking, Medieval and Later. Centre for Manx Studies Monographs. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. pp. 15–23. ISBN 0-85323-336-5.

- Imsen, S (2010). "Introduction". In Imsen, S (ed.). The Norwegian Domination and the Norse World c. 1100–c. 1400. Trondheim Studies in History. Trondheim: Tapir Academic Press. pp. 13–33. ISBN 978-82-519-2563-1.

- Wilson, DM (1973). "Manx Memorial Stones of the Viking Period" (PDF). Saga-Book. 18: 1–18.

- Insley, J; Wilson, D (2006). "Tynwald". Germanische Altertumskunde Online. De Gruyter. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- Johnsen, AO (1969). "The Payments From the Hebrides and Isle of Man to the Crown of Norway, 1153–1263: Annual Ferme or Feudal Casualty?". Scottish Historical Review. 48 (1): 18–64. eISSN 1750-0222. ISSN 0036-9241. JSTOR 25528786.

- Kermode, PMC (1915–1916). "Further Discoveries of Cross-Slabs in the Isle of Man" (PDF). Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 50: 50–62. eISSN 2056-743X. ISSN 0081-1564.

- Lewis, S (1987), The Art of Matthew Paris in Chronica Majora, California Studies in the History of Art, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-04981-0, OL 3163004M

- MacInnes, IA (2019). "'A Somewhat too Cruel Vengeance was Taken for the Blood of the Slain': Royal Punishment of Rebels, Traitors, and Political Enemies in Medieval Scotland, c.1100–c.1250". In Tracy, L (ed.). Treason: Medieval and Early Modern Adultery, Betrayal, and Shame. Explorations in Medieval Culture. Leiden: Brill. pp. 119–146. ISBN 978-90-04-40069-6. ISSN 2352-0299. LCCN 2019017096.

- MacLeod, N (2002). Raasay: The Island and its People. Edinburgh: Birlinn Limited. ISBN 1 84158 235 2 – via Questia.

- Matheson, W (1978–1980). "The Ancestry of the MacLeods". Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness. 51: 68–80.

- McDonald, RA (1997). The Kingdom of the Isles: Scotland's Western Seaboard, c. 1100–c. 1336. Scottish Historical Monographs. East Linton: Tuckwell Press. ISBN 978-1-898410-85-0.

- McDonald, RA (2004). "Coming in From the Margins: The Descendants of Somerled and Cultural Accommodation in the Hebrides, 1164–1317". In Smith, B (ed.). Britain and Ireland, 900–1300: Insular Responses to Medieval European Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 179–198. ISBN 0-511-03855-0.

- McDonald, RA (2007a). "Dealing Death From Man: Manx Sea Power in and around the Irish Sea, 1079–1265". In Duffy, S (ed.). The World of the Galloglass: Kings, Warlords and Warriors in Ireland and Scotland, 1200–1600. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 45–76. ISBN 978-1-85182-946-0.

- McDonald, RA (2007b). Manx Kingship in its Irish Sea Setting, 1187–1229: King Rǫgnvaldr and the Crovan Dynasty. Dublin: Four Courts Press. ISBN 978-1-84682-047-2.

- McDonald, RA (2008). "Man, Ireland, and England: The English Conquest of Ireland and Dublin-Manx Relations". In Duffy, S (ed.). Medieval Dublin. 8. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 131–149. ISBN 978-1-84682-042-7.

- McDonald, RA (2012). "The Manx Sea Kings and the Western Oceans: The Late Norse Isle of Man in its North Atlantic Context, 1079–1265". In Hudson, B (ed.). Studies in the Medieval Atlantic. The New Middle Ages. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 143–184. doi:10.1057/9781137062390_6. ISBN 978-1-137-06239-0.

- McDonald, RA (2016). "Sea Kings, Maritime Kingdoms and the Tides of Change: Man and the Isles and Medieval European Change, AD c1100–1265". In Barrett, JH; Gibbon, SJ (eds.). Maritime Societies of the Viking and Medieval World. The Society for Medieval Archaeology Monograph. Milton Park, Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 333–349. doi:10.4324/9781315630755. ISBN 978-1-315-63075-5. ISSN 0583-9106.

- McDonald, RA (2019). Kings, Usurpers, and Concubines in the Chronicles of the Kings of Man and the Isles. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-22026-6. ISBN 978-3-030-22026-6.

- McGrail, MJ (1995). The Language of Authority: The Expression of Status in the Scottish Medieval Castle (MA thesis). McGill University.

- McLeod, W (2002). "Rí Innsi Gall, Rí Fionnghall, Ceannas nan Gàidheal: Sovereignty and Rhetoric in the Late Medieval Hebrides". Cambrian Medieval Celtic Studies. 43: 25–48. ISSN 1353-0089.

- McNamee, C (2005). "Olaf (1173/4–1237)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (May 2005 ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/20672. Retrieved 5 July 2011.