Guantanamo Bay Naval Base

Guantanamo Bay Naval Base (Spanish: Base Naval de la Bahía de Guantánamo), officially known as Naval Station Guantanamo Bay or NSGB, (also called GTMO or Gitmo because of the common pronunciation of this word by the U.S. military[1]) is a United States military base on the shore of Guantánamo Bay and is also the oldest overseas U.S. Naval Base.[2] The base is located on 45 square miles (116 km2) of land and water at Guantánamo Bay, at the southeastern end of Cuba, which the U.S. leased for use as a coaling station and naval base in 1903. The lease was $2,000 in gold per year until 1934, when the payment was set to match the value in gold in dollars;[3] in 1974, the yearly lease was set to $4,085.[4]

| United States Naval Station Guantanamo Bay | |

|---|---|

| Guantánamo Bay, Cuba | |

Aerial view of McCalla Field, Guantanamo Bay (looking north-east) | |

| |

| Coordinates | 19°55′03″N 75°09′36″W |

| Type | Military base |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1898 |

| In use | 1898–present |

| Battles/wars | Battle of Guantánamo Bay |

| Garrison information | |

| Current commander | Captain John A. Fischer, USN |

Since the Cuban Revolution of 1959, the Cuban communist government has consistently protested against the U.S. presence on Cuban soil and called it "illegal" under international law, alleging that the base "was imposed on Cuba by force." Since 2002, the naval base has contained a military prison, for alleged unlawful combatants captured in Afghanistan, Iraq, and other places during the War on Terror.[5] Cases of torture of prisoners[6] by the U.S. military, and their denial of protection under the Geneva Conventions, have been criticized.[7][8]

Units and commands

Resident units

- Headquarters, Naval Station Guantanamo Bay

- Customer Service Desk (CSD)[9]

- Joint Task Force Guantanamo[9][10][11]

- Headquarters, JTF Guantanamo

- Joint Detention Group

- Joint Intelligence Group

- Joint Medical Group

- U.S. Coast Guard Maritime Security Detachment Guantanamo Bay

- Marine Corps Security Force Company[9]

- Naval Computer and Telecommunications Area Master Station Atlantic Detachment Guantanamo Bay[9]

- Naval Hospital Guantanamo Bay[10]

- Navy Supply[9]

- Navy Security Forces

- SEABEE Detachment

- U.S. Coast Guard Aviation Detachment Guantanamo Bay

Assigned units

Homeported watercraft

- YC 1639 (open lighter)[15][16][17]

- Leeward (YFB-92) (ferry boat)[15][18]

- Windward (YFB-93) (ferry boat)[15][19]

- YON 258 (non-self propelled fuel oil barge)[15][20]

- USS Wanamassa (YTB-820) (large Harbor Tug)[15][21]

- LCU 1671 and MK-8: landing craft used as an alternate ferry for transportation to areas inaccessible by the primary ferry and for moving hazardous cargo.[22]

- GTMO-5, GTMO-6 and GTMO-7 (50-ft. utility boats): used for personnel transportation during off-ferry hours.[22]

Civilian contractors

Besides servicemembers, the base houses a large number of civilian contractors working for the military. Many of these contractors are migrant workers from Jamaica and the Philippines, and are thought to constitute up to 40% of the base's population.[23]

Major contractors working at NSGB have included the following:

- KBR

- Schuyler Line Navigation Company (SYLF)

- Satellite Communication Systems Incorporated

- Centerra

- EMCOR

- Islands Mechanical Contractor

- Munilla Construction Management

- RQ Construction

- MCM Construction

- J&J Worldwide Services

Cargo shipping

Ocean transportation is provided by Schuyler Line Navigation Company, a U.S. Flag Ocean Carrier. Schuyler Line operates under government contract to supply sustainment and building supplies to the base.[24]

History

Spanish colonial era

The area surrounding Guantanamo bay was originally inhabited by the Taíno people.[25] On 30 April 1494, Christopher Columbus, on his second voyage, arrived and spent the night. The place where Columbus landed is now known as Fisherman's Point. Columbus declared the bay Puerto Grande.[26] The bay and surrounding areas came under British control during the War of Jenkins' Ear. Prior to British occupation, the bay was referred to as Walthenham Harbor. The British renamed the bay Cumberland Bay. The British retreated from the area after a failed attempt to march to Santiago de Cuba.[26]

Guantanamo Bay during the Spanish–American War

During the Spanish–American War, the U.S. fleet attacking Santiago[27] secured Guantánamo's harbor for protection during the hurricane season of 1898. The Marines landed at Guantanamo Bay with naval support, and American and Cuban forces routed the defending Spanish troops. The war ended with the Treaty of Paris of 1898, in which Spain formally relinquished control of Cuba. Although the war was over, the United States maintained a strong military presence on the island. In 1901 the United States government passed the Platt Amendment as part of an Army Appropriations Bill.[28] Section VII of this amendment read

That to enable the United States to maintain the independence of Cuba, and to protect the people thereof, as well as for its own defense, the government of Cuba will sell or lease to the United States lands necessary for coaling or naval stations at certain specified points to be agreed upon with the President of the United States

After initial resistance by the Cuban Constitutional Convention, the Platt Amendment was incorporated into the Constitution of the Republic of Cuba in 1901.[29] The Constitution took effect in 1902, and land for a naval base at Guantanamo Bay was granted to the United States the following year.[30]

USS Monongahela (1862), an old warship which served as a storeship at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba was totally destroyed by fire on 17 March 1908. A 4-inch gun was salvaged from her wreck and put on display at the Naval Station. Since the gun was deformed by the heat from the fire, it was nicknamed "Old Droopy". The gun was on display on Deer Point until the command disposed of it, judging its appearance less than exemplary of naval gunnery.

Lease

Long name:

| |

|---|---|

| Signed | 16 February 1903; 23 February 1903 |

| Location | Havana; Washington |

| Effective | 23 February 1903 |

| Signatories | |

| Citations | TS 418; 6 Bevans 1113 |

Long name:

| |

|---|---|

| Signed | 2 July 1903 |

| Location | Havana |

| Effective | 6 October 1903 |

| Signatories | |

| Citations | TS 426; 6 Bevans 1120 |

The 1903 lease agreement was executed in two parts. The first, signed in February, consisted of the following provisions:[30]

- Agreement – This is a lease between the U.S. and Cuba for properties for naval stations, in accord with Article VII of the Platt Amendment.

- Article 1 – Describes the boundaries of the areas being leased, Guantanamo Bay and Bahia Honda.

- Article 2 – The U.S. may occupy, use, and modify the properties to fit the needs of a coaling and naval station, only. Vessels in the Cuban trade shall have free passage.

- Article 3 – Cuba retains ultimate sovereignty, but during the occupation, the U.S. exercises sole jurisdiction over the areas described in Article 1. Under conditions to be agreed on, the U.S. has the right to acquire, by purchase or eminent domain, any land included therein.

The second part, signed five months later in July 1903, consisted of the following provisions:[31]

- Article 1 – Payment is $2000 gold coin, annually. All private lands within the boundaries shall be acquired by Cuba. The U.S. will advance rental payments to Cuba to facilitate those purchases.

- Article 2 – The U.S. shall pay for a survey of the sites and mark the boundaries with fences.

- Article 3 – There will be no commercial or other enterprise within the leased areas.

- Article 4 – Mutual extradition

- Article 5 – Not ports of entry.

- Article 6 – Ships shall be subject to Cuban port police. The U.S. will not obstruct entry or departure into the bay.

- Article 7 – This proposal is open for seven months.

SIGNED Theodore Roosevelt and Jose M Garcia Montes.

In 1934, the United States unilaterally changed the payment from gold coin to U.S. dollars per the Gold Reserve Act. The lease amount was set at US$3,386.25, based on the price of gold at the time.[32] In 1973, the U.S. adjusted the lease amount to $3,676.50, and in 1974 to $4,085, based on further increases to the price of gold in USD.[33] Payments have been sent annually, but only one lease payment has been accepted since the Cuban Revolution and Fidel Castro claimed that this check was deposited due to confusion in 1959. The Cuban government has not deposited any other lease checks since that time.[34]

The 1903 Lease for Guantanamo has no fixed expiration date.[35]

World War II

During World War II, the base was set up to use a nondescript number for postal operations. The base used the Fleet Post Office, Atlantic, in New York City, with the address: 115 FPO NY.[36] The base was also an important intermediate distribution point for merchant shipping convoys from New York City and Key West, Florida, to the Panama Canal and the islands of Puerto Rico, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago.[37]

1958–99

Until the 1953–59 revolution, thousands of Cubans commuted daily from outside the base to jobs within it. In mid-1958, vehicular traffic was stopped; workers were required to walk through the base's several gates. Public Works Center buses were pressed into service almost overnight to carry the tides of workers to and from the gate.[38]

During the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, the families of military personnel were evacuated from the base. Notified of the evacuation on 22 October, evacuees were told to pack one suitcase per family member, to bring evacuation and immunization cards, to tie pets in the yard, to leave the keys to the house on the dining table, and to wait in front of the house for buses.[39] Dependents travelled to the airfield for flights to the United States, or to ports for passage aboard evacuation ships. After the crisis was resolved, family members were allowed to return to the base in December 1962.[40]

From 1939, the base's water was supplied by pipelines that drew water from the Yateras River about 4.5 miles (7 km) northeast of the base. The U.S. government paid a fee for this; in 1964, it was about $14,000 a month for about 2,500,000 U.S. gallons (9,000 m3) per day. In 1964, the Cuban government stopped the flow. The base had about 14,000,000 U.S. gallons (50,000 m3) of water in storage, and strict water conservation was put into effect immediately. The U.S. first imported water from Jamaica by barge, then relocated a desalination plant from San Diego (Point Loma).[41] When the Cuban government accused the United States of stealing water, base commander John D. Bulkeley ordered that the pipelines be cut and a section removed. A 38 in (970 mm) length of the 14 in (360 mm) diameter pipe and a 20 in (510 mm) length of the 10 in (250 mm) diameter pipe were lifted from the ground and the openings sealed.

21st century

The military facilities at Guantanamo Bay have over 8,500 U.S. sailors and Marines stationed there.[42][43] It is the only military base the U.S. maintains in a communist country.

In 2005, the U.S. Navy completed a $12 million wind-power project at the base, erecting four 950-kilowatt, 275-foot-tall wind turbines, reducing the need for diesel fuel to power the existing diesel generators (the base's primary electricity generation).[44][45] In 2006, the wind turbines reduced diesel fuel consumption by 650,000 gallons annually.[46]

By 2006, only two elderly Cubans, Luis Delarosa and Harry Henry, still crossed the base's North East Gate daily to work on the base, because the Cuban government prohibited new recruitment since its revolution. They both retired at the end of 2012.[47]

In January 2009, President Obama signed executive orders directing the CIA to shut what remains of its network of "secret" prisons and ordering the closing of the Guantánamo detention camp within a year.[48] However, he postponed difficult decisions on the details for at least six months.[49] On 7 March 2011, President Obama issued an executive order that permits ongoing indefinite detention of Guantánamo detainees.[50] The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012 authorized indefinite detention of suspected terrorists,[51] but enforcement of the relevant section was temporarily blocked by a federal court ruling in the case of Hedges v. Obama on 16 May 2012,[52] a suit brought by a number of private citizens, including Chris Hedges, Daniel Ellsberg, Noam Chomsky, and Birgitta Jónsdóttir.[53] After a series of decisions and appeals, the lawsuit was vacated because the plaintiffs lacked standing to file the suit.[54] As of April 2018, the detention center was in operation.

At the United Nations Human Rights Council in 2013, Cuba's Foreign Minister demanded the U.S. return the base and the "usurped territory" which the Cuban government considers to be occupied since the U.S. invasion of Cuba during the Spanish–American War in 1898.[55][56][57][58][59]

Geography

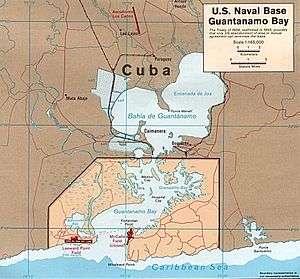

The Naval Base is divided into three main geographical sections: Leeward Point, Windward Point, and Guantánamo Bay. Guantánamo Bay physically divides the Naval Station into sections. The bay extends past the boundaries of the base into Cuba, where the bay is then referred to as Bahía de Guantánamo. Guantánamo Bay contains several cays, which are identified as Hospital Cay, Medico Cay, North Toro Cay, and South Toro Cay.

Leeward Point of the Naval Station is the site of the active airfield. Major geographical features on Leeward Point include Mohomilla Bay and the Guantánamo River. Three beaches exist on the Leeward side. Two are available for use by base residents, while the third, Hicacal Beach, is closed.

Windward Point contains most of the activities at the Naval Station. There are nine beaches available to base personnel. The highest point on the base is John Paul Jones hill at a total of 495 feet (151 m).[11] The geography of Windward Point is such that there are many coves and peninsulas along the bay shoreline providing ideal areas for mooring ships.

Cactus Curtain

Cactus Curtain is a term describing the line separating the naval base from Cuban-controlled territory. After the Cuban Revolution, some Cubans sought refuge on the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base. In late 1961, Cuban troops planted an 8-mile (13 km) barrier of Opuntia cactus along the northeastern section of the 17-mile (27 km) fence surrounding the base to stop Cubans from escaping Cuba to take refuge in the United States.[60] This was dubbed the Cactus Curtain, an allusion to Europe's Iron Curtain,[61] the Bamboo Curtain in East Asia or the similar Ice Curtain in the Bering Strait.

U.S. and Cuban troops placed some 55,000 land mines across the "no man's land" around the perimeter of the naval base creating the second-largest minefield in the world, and the largest in the Western Hemisphere. On 16 May 1996, U.S. President Bill Clinton ordered the demining of the American field. They have since been replaced with motion and sound sensors to detect intruders on the base. The Cuban government has not removed its corresponding minefield outside the perimeter.[62][63]

Detention camp

In the last quarter of the 20th century, the base was used to house Cuban and Haitian refugees intercepted on the high seas. In the early 1990s, it held refugees who fled Haiti after military forces overthrew president Jean-Bertrand Aristide. These refugees were held in a detainment area called Camp Bulkeley until United States district court Judge Sterling Johnson, Jr. declared the camp unconstitutional on 8 June 1993. This decision was later vacated. The last Haitian migrants departed Guantanamo on 1 November 1995.

Beginning in 2002, some months after the War on Terror started in response to the September 11 attacks, a small portion of the base was used to detain several hundred enemy combatants at Camp Delta, Camp Echo, Camp Iguana, and the now-closed Camp X-Ray. The U.S. military has alleged without formal charge that some of these detainees are linked to al-Qaeda or the Taliban. In litigation regarding the availability of fundamental rights to those imprisoned at the base, the U.S. Supreme Court has recognized that the detainees "have been imprisoned in territory over which the United States exercises exclusive jurisdiction and control."[64] Therefore, the detainees have the fundamental right to due process of law under the Fifth Amendment. A district court has since held that the "Geneva Conventions applied to the Taliban detainees, but not to members of Al-Qaeda terrorist organization."[65]

On 10 June 2006, the Department of Defense reported that three Guantanamo Bay detainees committed suicide. The military reported the men hanged themselves with nooses made of sheets and clothes.[66] A study published by Seton Hall Law's Center for Policy and Research, while making no conclusions regarding what actually transpired, asserts that the military investigation failed to address significant issues detailed in that report.[67]

On 6 September 2006, President George W. Bush announced that alleged or non-alleged combatants held by the CIA would be transferred to the custody of Department of Defense, and held at Guantanamo Prison. Of approximately 500 prisoners in Guantanamo Bay, only 10 have been tried by the Guantanamo military commission, but all cases have been stayed pending the adjustments being made to comply with the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Hamdi v. Rumsfeld.

President Barack Obama said he intended to close the detention camp, and planned to bring detainees to the United States to stand trial by the end of his first term in office. On 22 January 2009, he issued three executive orders. Only one of these explicitly dealt with policy at the Guantanamo Bay detention camp, and directed the camp's closure within one year. All three could have possibly impacted the detention center, as well as how the United States holds detainees.

While mandating closure of the detention camp, the naval base as a whole is not subject to the order and will remain operational indefinitely. This plan was thwarted for the time being on 20 May 2009, when the United States Senate voted to keep the prison at Guantanamo Bay open for the foreseeable future and forbid the transfer of any detainees to facilities in the United States. Senator Daniel Inouye, a Democrat from Hawaii and chairman of the appropriations committee, said he initially favored keeping Guantanamo open until Obama produced a "coherent plan for closing the prison."[68] As of January 2017, 45 detainees remain at Guantanamo.[69]

Represented businesses

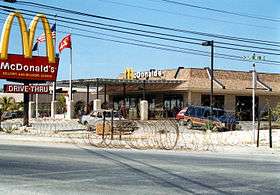

Despite the prohibition on the establishment of "commercial or other enterprises" as stated in Article 3 of the second part of the lease, several businesses have been opened in the military base. A Baskin-Robbins ice cream stand, which opened in the 1980s, was one of the first business franchises allowed on the base.[70] In early 1986, the base added the first and only McDonald's restaurant within Cuba.[71][72] A Subway restaurant was opened in 2002.[73] In 2004, a combined KFC & A&W restaurant was opened at the bowling alley and a Pizza Hut Express was added to the Windjammer Restaurant.[74] There is also a cafe that sells Starbucks coffee, and there is a combined KFC & Taco Bell restaurant.[75]

All the restaurants on the installation are franchises owned and operated by the Department of the Navy.[76] All proceeds from these restaurants are used to support morale, welfare, and recreation (MWR) activities for service personnel and their families.[77] These restaurants are located inside the base; as such, they are not accessible to Cubans.

Airfields

There are two airfields within the base, Leeward Point Field and McCalla Field. Leeward Point Field is the active military airfield, with the ICAO code MUGM and IATA code NBW.[78] McCalla Field was designated as the auxiliary landing field in 1970.[10]

Leeward Point Field was constructed in 1953 as part of Naval Air Station (NAS) Guantanamo Bay.[79] Leeward Point Field has a single active runway, 10/28, measuring 8,000 ft (2,400 m).[78] The former runway, 9/27 was 8,500 ft (2,600 m). Currently, Leeward Point Field operates several aircraft and helicopters supporting base operations. Leeward Point Field was home to Fleet Composite Squadron 10 (VC-10) until the unit was phased out in 1993. VC-10 was one of the last active-duty squadrons flying the Douglas A-4 Skyhawk.

McCalla Field was established in 1931[79] and remained operational until 1970. Naval Air Station Guantanamo Bay was officially established 1 February 1941. Aircraft routinely operating out of McCalla included JRF-5, N3N, J2F, C-1 Trader,[80] and dirigibles. McCalla Field is now listed as a closed airfield. The area consists of 3 runways: 1/19 at 4,500 ft (1,400 m), 14/32 at 2,210 ft (670 m), and 10/28 at 1,850 ft (560 m). Camp Justice is now located on the grounds of the former airfield.

Access to the Naval Station is very limited and must be preapproved through the appropriate local chain of command with the Commander of the station as the final approval. Since berthing facilities are limited, visitors must be sponsored indicating that they have an approved residence for the duration of the visit.[81]

Education

Department of Defense Education Activity (DoDEA) provides for the education of dependent personnel with two schools. Both schools are named for Rear Admiral William Thomas Sampson. W.T. Sampson Elementary School serves grades K–5 and W. T. Sampson High School serves grades 6–12. The Villamar Child Development Center provides child care for dependents from six weeks to five years old. MWR operates a Youth Center that provides activities for dependents.[82]

Some former students of Guantánamo have shared stories of their experiences with the Guantánamo Public Memory Project.[83] The 2013 documentary Guantanamo Circus directed by Christina Linhardt and Michael Rose reveals a glimpse of day-to-day life on GTMO as seen through the eyes of circus performers that visit the base.[84] It is used as a reference by the Guantánamo Public Memory Project.

Climate

U.S. Naval Station Guantanamo Bay has an annual rainfall of about 24 in (610 mm).[85] The amount of rainfall has resulted in the base being classified as a semi-arid desert environment.[85] The annual average high temperature on the base is 88.2 °F (31.2 °C), the annual average low is 72.5 °F (22.5 °C).

| Climate data for Guantanamo Bay | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F (°C) | 84 (29) |

84 (29) |

86 (30) |

88 (31) |

88 (31) |

90 (32) |

91 (33) |

91 (33) |

91 (33) |

90 (32) |

88 (31) |

86 (30) |

88.2 (31.2) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 68 (20) |

68 (20) |

70 (21) |

72 (22) |

73 (23) |

75 (24) |

75 (24) |

75 (24) |

75 (24) |

75 (24) |

73 (23) |

70 (21) |

72.5 (22.5) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.0 (25) |

0.9 (23) |

1.2 (30) |

1.3 (33) |

3.6 (91) |

2.1 (53) |

1.1 (28) |

1.9 (48) |

3.1 (80) |

5.1 (130) |

1.8 (46) |

1.1 (28) |

24.4 (620) |

| Source: Weatherbase[86] | |||||||||||||

Notable people

Notable people born at the naval base include actor Peter Bergman[87] and American guitarist Isaac Guillory.[88]

See also

- COVID-19 pandemic in the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base

- Cuba–United States relations

- Platt Amendment

- The Road to Guantanamo – A docudrama directed by Michael Winterbottom about the incarceration of three British detainees at Guantanamo Bay Naval Base.

- Panama Canal Zone

- Suez Canal Zone

- Irish treaty ports

- British Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia

- Soviet Naval Base at Hanko

- Soviet Naval Base at Porkkala

Notes

References

- "File:US Navy 040813-N-6939M-002 Commissions building courtroom at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.jpg".

- "Why the U.S. base at Cuba's Guantanamo Bay is probably doomed". Washington Post. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- Sweeney, Joseph C. (2006). "Guantanamo and U.S. Law". Fordham International Law Journal. 30 (3): 22.

- Elsea, Jennifer K.; Else, Daniel H. (17 November 2016). Naval Station Guantanamo Bay: History and Legal Issues Regarding Its Lease Agreements (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- "Guantanamo Bay – Camp Delta". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- "GTMO CTD Inspection Special Inquiry" (PDF). Federal Bureau of Investigation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- "Article 10: Right to fair public hearing by independent tribunal". BBC World Service. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- "Agenda Item 17 base naval". cubaminrex.cu. Archived from the original on 4 June 2004.

- "Tenant Commands". United States Navy. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- "The History of Guantanamo Bay, Vol. II 1964–1982". United States Navy. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- "Guantanamo Bay [GTMO] "GITMO"". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- "CNO: Shore and Fleet Organization Branch (SNDL) Collection COLL/94" (PDF). United States Navy. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- "US Naval Station Guantanamo Bay, Cuba". Net Resources International. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- "Fleet Training Group Moves to Mayport". All Hands (939): 2. July 1995.

- "Naval Station Guantanamo Bay, CU (NAVSTA) Custodian Assignments". Naval Vessel Register. Archived from the original on 3 September 2015. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- "No Name (YC 1639) Open Lighter (NSP)". Naval Vessel Register. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- "YC – Open Lighter". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- "Leeward (YFB) Ferryboat or Launch (S-P)". Naval Vessel Register. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- "Windward (YFB93)". Naval Vessel Register. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- "No Name (YON 258) Fuel Oil Barge (N-S-P)". Naval Vessel Register. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- "Wanamassa (YTB 820) Large Harbor Tug (S-P)". Naval Vessel Register. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- "Port Operations". United States Navy. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- Li, Darryl (2015), "Offshoring the Army: Migrant Workers and the U.S. Military", UCLA Law Review, 62: 124–174, SSRN 2459268

- Guantanamo Bay, Cuba Liner Service Schuyler Line Navigation Company

- Robert M. Poole. "What Became of the Taino". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- M. E. Murphy. "The History of Guantanamo Bay 1494–1964". United States Navy. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- "The Santiago Campaign | Battlefields | Cuban Battlefields of the Spanish-Cuban-American War". cubanbattlefields.unl.edu. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- 1901 Platt Amendment commentary at the United States Archives online

- "The Platt Amendment is Accepted by Cuba" (PDF). New York Times. 13 June 1901. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- Agreement Between the United States and Cuba for the Lease of Lands for Coaling and Naval stations, 1903.

- Lease to the United States by the Government of Cuba of Certain Areas of Land and Water for Naval or Coaling Stations in Guantanamo and Bahia Honda U.S. Federal Government, 1903.

- Central Bank Gold Reserves

- Strauss, Michael (2009). The Leasing of Guantanamo Bay. Praeger Security International. p. 246 and viii. ISBN 978-0-313-37782-2.

- Boadle, Anthony (17 August 2007). "Castro: Cuba not cashing US Guantanamo rent checks". Reuters. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- Suellentrop, Chris (18 January 2002). "How Did the U.S. Get a Naval Base in Cuba?". The Slate. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- "World War II Navy Post Office Numbers".

- Hague, Arnold The Allied Convoy System 1939–1945 Naval Institute Press 2000 ISBN 1-55750-019-3 p.111

- M. E. Murphy; Rear Admiral; U.S. Navy. "The History of Guantanamo Bay 1494–1964: Chapter 18, "Introduction of Part II, 1953 – 1964"". Retrieved 15 March 2006.

- M. E. Murphy. "The History of Guantánamo Bay 1494–1964: Chapter 19, "Cuban Crisis, 1962"". Retrieved 15 March 2006.

- "History of the American Red Cross Station on NSGB". United States Navy.

- John Pomfret, Captain, U.S. Marine Corps. "The History of Guantanamo Bay". Ch. 1, After the Cuban Missile Crisis, 1968. Retrieved 31 March 2008.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "US Naval Station Guantanamo Bay". Naval Technology. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- Ralston, Jeannie (April 2005). "09360 No-Man's-Land". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 16 March 2006.

- Virginia Bueno (25 April 2011). "Navy's New Wind Turbines to Save Taxpayers $1.2 Million in Annual Energy Costs" (Press release). Naval Facilities Engineering Command.

- Annie Snider, Could Alternative Energy Be Gitmo's Next Legacy?, Greenwire (republished by the New York Times) (13 June 2011).

- Wind turbines at U.S. Naval Station Guantanamo Bay reduce fuel consumption by 650,000 gallons annually 30 July 2006

- Suzette Leboy; Ben Fox. "Era Ends: Base's last two Cuban commuters retire". Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- Shane, Scott (23 January 2009). "Obama Orders Secret Prisons and Detention Camps Closed". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 January 2009.

- Warren Richey (15 October 2009). "Obama's Guantánamo, Counterterror Policies Similar to Bush's?". Christian Science Monitor..

- "President Obama Issues Executive Order Institutionalizing Indefinite Detention" (Press release). American Civil Liberties Union. 7 March 2011.

- "Obama Makes It Official: Suspected Terrorists Can Be Indefinitely Detained Without a Trial". The Atlantic. 31 December 2011.

- "Judge Blocks Controversial NDAA". Courthousenews.com]. 16 May 2012. Archived from the original on 20 May 2012.

- Kuipers, Dean (18 April 2012). "Activists sue Obama, others over National Defense Authorization Act". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- Hurley, Lawrence (28 April 2014). "Supreme Court rejects hearing on military detention case". Reuters. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- Australian News, May 2013, Comments by Cuba to the UN Human Rights Council

- Granma, 26 January 2012 Archived 3 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine, comments on an article in the New York Times on the continued occupation of Cuba

- New York Times, 10 January 2012, Give Guantanamo Back to Cuba, Jonathan M. Hansen, cited in Granma

- Guantanamo, Yankee naval base of crimes and provocations, 1970, (Cuban) Ministry of Foreign Affairs, translated 1977 by U.S. Joint Publications Research Service (PDF)

- Alfred de Zayas, "The Status of Guantanamo Bay and the Status of the Detainees" in University of British Columbia Law Review, vol. 37, July 2004, pp. 277–342;, A de Zayas Guantanamo Naval Base in Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, Oxford University Press 2012

- "Guantanamo Bay Naval Base and Ecological Crises". Trade and Environment Database. American University. Archived from the original on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 19 April 2009.

- "Yankees Besieged". Time. 16 March 1962.

- Rosenberg, Carol (29 June 1999). "Guantanamo base free of land mines". Miami Herald. Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- "Destination Guantanamo Bay". BBC News. 28 December 2001. Retrieved 15 March 2006.

- Rasul v. Bush, 542 U.S. 466 (2004).

- In re Guantanamo detainee Cases, 355 F.Supp.2d 443 (D.D.C. 2005).

- DOD Identifies 3 Guantanamo Suicides, The Washington Post, 11 June 2006

- Death in Camp Delta, Seton Hall University School of Law. (18 MB)

- "Senate Nixes Obama's Guantanamo Plan". CBC News. 20 May 2009. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- Myre, Greg (16 January 2017). "10 Guantanamo Prisoners Freed In Oman; 45 Detainees Remain".

- "U.S.-CUBAN FACE-OFF JUST DAILY DRUDGERY". Chicago Tribune. 20 December 1985. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- Warner, Margaret (14 October 2003). "INSIDE GUANTANAMO". Online NewsHour. Retrieved 15 March 2006.

- Joseph A. Morris (15 November 2002). "Profession of the Week: McDonald's workers" (PDF). The Wire (JTF-GTMO). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2012. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- Frank N. Pellegrini (22 November 2002). "Monday Night Football at Subways: Open until it is over" (PDF). The Wire. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2012. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- "Dining". JTF Guantanamo. Archived from the original on 3 December 2008. Retrieved 22 January 2009.

- "The Military Spent $1.45 Million Opening a Starbucks and a KFC/Taco Bell in Guantanamo Bay". 9 June 2010. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- Andrew Selsky (27 November 2008). "Not just a prison, the Navy sees many uses for Guantanamo". Miami Herald. Archived from the original on 30 November 2008. Retrieved 28 November 2008.

- Morale, Welfare and Recreation. "Branded Food & Beverage Concepts". U.S. Navy. Archived from the original on 14 April 2009. Retrieved 22 January 2010.

- "Guantanamo Bay NS". WorldAeroData. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- "Guantanamo Bay" (PDF). Naval Aviation News. United States Navy. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- Gillcrest, Paul (2000). "35 McCalla Field". Sea Legs. iUniverse. ISBN 978-1-4697-9797-7.

- "Section 1: General Entry Requirements" (PDF). United States Navy. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- "Naval Station Guantanamo Bay, Cuba". Department of Defense. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- "Guantánamo Stories". Guantánamo Public Memory Project. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- Guantanamo Circus (2013) – IMDb IMDB

- Stephen A. Lisio (June 1994). "Guantanamo Bay Naval Base and Ecological Crises". American University. Archived from the original on 27 March 2009.

- "Weatherbase: Historical Weather for Guantanamo Bay, Cuba". Weatherbase. 2011. Retrieved on 24 November 2011.

- "Peter Bergman Biography". CBS.

- Flynn, Nicholas (11 January 2001). "Obituary of Isaac Guillory". The Independent (London).

Further reading

- Jonathan M. Hansen, Guantánamo: An American History. New York: Hill and Wang, 2011.

- Alfred de Zayas, "The Status of Guantanamo Bay and the Status of the Detainees" in University of British Columbia Law Review, vol. 37, July 2004, pp. 277–34;, A de Zayas Guantanamo Naval Base in Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, Oxford University Press 2012)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Naval Station Guantanamo Bay. |

| Wikinews has news related to: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Official U.S. Military website

- Maps and photos