Jish

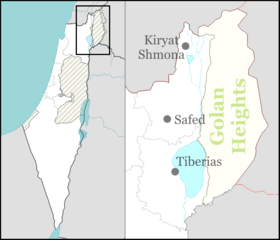

Jish (Arabic: الجش; Hebrew: גִ'שׁ, גּוּשׁ חָלָב,[2][3] Gush Halav) is a local council in Upper Galilee, located on the northeastern slopes of Mount Meron, 13 kilometres (8.1 mi) north of Safed, in Israel's Northern District.[4] In 2019 it had a population of 3,105,[1] which is predominantly Maronite Catholic and Melkite Greek Catholic Christians (63%), with a Sunni Muslim Arab minority (about 35.7%).[5][6]

Jish

| |

|---|---|

| Hebrew transcription(s) | |

| • ISO 259 | Ǧiš, Guš Ḥalab |

Jish  Jish | |

| Coordinates: 33°1′34″N 35°26′43″E | |

| Grid position | 191/270 PAL |

| Country | |

| District | Northern |

| Founded | 2000 BC (Earliest settlement) 1300 BC (Gush Halav) |

| Government | |

| • Type | Local council |

| • Head of Municipality | Elias Elias |

| Area | |

| • Total | 6,916 dunams (6.916 km2 or 2.670 sq mi) |

| Population (2019)[1] | |

| • Total | 3,105 |

| • Density | 450/km2 (1,200/sq mi) |

| Website | www |

Archaeological finds in Jish include two historical synagogues, a unique mausoleum and burial caves from classic era.[7] According to Roman historian Josephus (War 4:93), Gischala was the last city in the Galilee to fall to the Romans during the First Jewish–Roman War.[8] Historical sources dating from the 10th-15th centuries describe Jish (Gush Halav) as a village with a strong Jewish presence.[7] In the early Ottoman era Jish was wholly Muslim.[9] In the 17th century, the village was inhabited by Druze.[7] In 1945, under the British rule, Jish had a population of 1,090 with an area of 12,602 dunams. It was largely depopulated during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, but was resettled not only by the original inhabitants who were at large Maronite Christians, but also by some Maronite Christians who were expelled from the razed villages Kafr Bir'im and some Muslims who were expelled from Dallata.[10][11]

In 2010, the population of Jish was 3,000.[11]

Etymology

Jish is the ancient Giscala [12]. The Arabic name el-Jish is a variation of the site's ancient name Gush Halav in Hebrew,[13] literally "abundance of milk", which may be a reference to the production of milk and cheese (for which the village has been famous since at least the early Middle Ages[8]) or to the fertile surroundings.[14] Other scholars believe the name Gush Halav refers to the light color of the local limestone, which contrasted with the dark reddish rock of the neighboring village, Ras al-Ahmar.[8]

History

Bronze and Iron Age

Settlement in Jish dates back 3,000 years. The village is mentioned in the Mishnah as Gush Halav, a city "surrounded by walls since the time of Joshua Ben Nun" (m. Arakhin 9:6).[15] Canaanite and Israelite remains from the Early Bronze and Iron Ages have been found there.[8]

Classical antiquity

During the Classical era the town was known as Gischala, a Greek transcription of the Hebrew name Gush Halav. Both Josephus and later Jewish sources from the Roman-Byzantine period mention the fine olive oil for which the village was known.[14] According to the Talmud, the inhabitants also engaged in the production of silk.[8] Eleazar b. Simeon, described in the Talmud as a very large man with tremendous physical strength, was a resident of the town. He was initially buried in Gush Halav but later reinterred in Meron, next to his father, Shimon bar Yochai.[16] Jerome recorded that Paul the Apostle lived with his parents in "Giscalis in Judea", which is understood to be Gischala.[17][18][19]

After the fall of Gamla, Gush Halav was the last Jewish stronghold in the Galilee and Golan region during the First Jewish Revolt against Rome (66-73 CE). Gischala was the home of Yohanan mi-Gush Halav, known in English as John of Gischala, a wealthy olive oil merchant who became the chief commander in the Jewish revolt in the Galilee and later Jerusalem.[20] Initially known as a moderate, John changed his stance when Titus arrived at the gates of Gischala accompanied by 1,000 horsemen and demanded the town's surrender.[21]

In addition to Jewish burial sites and structures dated to 3rd - 6th centuries,[7] Jewish-Christian amulets were discovered nearby.[22] Christian artifacts from the Byzantine period have been found at the site.[23] The synagogue of Gush Halav went through several phases of construction and reconstruction, one destruction being dated by excavator Eric M. Meyers to the earthquake of 551.[24]

Early Muslim, Crusader, and Mamluk periods

Jish acquired its modern name in the Middle Ages.[7] Historical sources from the 10th-15th centuries describe it as a large Jewish village[7] and it is mentioned in the 10th century by Arab geographer Al-Muqaddasi.[25] Jewish life in the 10th and 11th centuries is attested to by documents in the Cairo Geniza. In 1172, the Jewish traveler Benjamin of Tudela found about 20 Jews living there.[26] Ishtori Haparchi also attended a megilla reading when he visited in 1322.[16]

Ottoman period

In 1596, Jish appeared in Ottoman tax registers as being in the Nahiya of Jira, of the Liwa Safad. It had a population of 71 households and 20 bachelors; all Muslim. The villagers paid taxes on goats and beehives, but most of its taxes were in the form of a fixed sum, total taxes were 30,750 akçe.[9][27]

In the 17th century, the village was inhabited by Druze.[7] The Turkish traveler Evliya Çelebi, who passed by the village in 1648, wrote

Then comes the village of Jish, with one hundred houses of accursed believers in the transmigration of souls (tenāsukhi mezhebindén). Yet what beautiful boys and girls they have! And what a climate! Every one of these girls has queenly, gazelle-like, bewitching eyes, which captivate the beholder—an unusual sight.[28]

The Galilee earthquake of 1837 caused widespread damage and over 200 deaths.[7] Three weeks afterward, contemporaries reported "a large rent in the ground...about a foot wide and fifty feet long." All the Galilee villages that were badly damaged at the time, including Jish, were situated on the slopes of steep hills. The presence of old landslides has been observed on aerial photographs. The fact that the village was built on dip slopes consisting of soft bedrock and soil has made it more vulnerable to landslides.[29] According to Andrew Thomson, no houses in Jish were left standing. The church fell, killing 130 people and the old town walls collapsed. A total of 235 people died and the ground was left fissured.[30][29] At the time, the village was noted as a mixed Muslim and Maronite village in the Safad district.[31]

At the end of the 19th century, Jish was described as a "well-built village of good masonry" with about 600 Christian and 200 Muslim inhabitants.[32]

A population list from about 1887 showed El Jish to have about 1,935 inhabitants; 975 Christians and 960 Muslims.[33]

British Mandate

At the time of the 1922 census of Palestine, Jish had a population of 721; 380 Christians and 341 Muslims.[34] The Christians were classified as 71% Maronite and 29% Greek Catholic (Melchite).[35] By the 1931 census, Jish had 182 inhabited houses and a population of 358 Christians and 397 Muslims.[36]

In the 1945 statistics, Jish had a population of 1,090; 350 Christians and 740 Muslims,[37] and the village spanned 12,602 dunams, mostly Arab-owned.[38] Of this, 1,506 dunums were plantations and irrigable land, 6,656 used for cereals,[39] while 72 dunams were built-up (urban) land.[40]

State of Israel

Israeli forces captured Jish on 29 October 1948, in Operation Hiram,[41] after "a hard-fought battle."[42] Benny Morris reports allegations that ten prisoners of war, identified as Moroccans fighting with the Syrian Army, and a number of villagers, including a woman and her baby, were murdered.[43] The Israeli prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, ordered an investigation of the deaths[44] but no IDF soldiers were brought to trial.[45]

Elias Chacour, now Archbishop of the Melkite Greek Catholic Church, whose family resettled in Jish, wrote that when he was eight years old he discovered a mass grave containing two dozen bodies.[46]

Many of the residents of Jish forced to leave the village in 1948 fled to Lebanon and became Palestinian refugees. Christians from the nearby town of Kafr Bir'im resettled in Lebanon and Jish,[10][11] where today they are citizens of Israel, but continue to press for their right of return to their former villages.[10] In October 1950, Israeli forces raided Jish and detained seven suspected smugglers who were stripped, bound and beaten. They were released without charge.[47]

In December 2010, a hiking and bicycle path known as the Coexistence Trail was inaugurated, linking Jish with Dalton, a neighboring Jewish village. The 2,500 meter-long trail, accessible to people with disabilities, sits 850 meters above sea level and has several lookout points, including a view of Dalton Lake, where rainwater is collected and stored for agricultural use.[48]

Today Jish is known for its efforts to revive Aramaic as a living language. In 2011, the Israeli Ministry of Education approved a program to teach the language in Jish elementary schools. Maronites in Jish say that Aramaic is essential to their existence as a people, in the same way that Hebrew and Arabic are for Jews and Arabs.[11]

Demographics

Today, 55% of the inhabitants of Jish are Maronite Christians, 10% percent are Melkites and 35% percent are Muslims.[5][6] The population of the village was 3,105.

Geography

Jish is located in Upper Galilee, in the Northern district of Israel. The town is close to Mount Meron, the tallest standing mountain of Galilee. Recently, a new road has connected Jish with the nearby Jewish village of Dalton.

Religious sites and shrines

According to Christian tradition, the parents of Saint Paul were from Jish.[49] John of Giscala, the son of Levi, was born in Jish. Other churches in Jish are a small Maronite Church that was rebuilt after the 1837 earthquake and the Elias Church, the largest in the village, which operates a convent.[50]

The tombs of Shmaya and Abtalion, Jewish sages who taught in Jerusalem in the early 1st century, are located in Jish.[14] According to tradition, the prophet Joel was also buried there.[50]

Archaeology

Eighteen archaeological sites have been excavated to date in Jish and vicinity. Archaeologists have excavated a synagogue in use from the 3rd to 6th centuries CE.[7] Jewish-Christian amulets were discovered nearby.[22]

Coins indicate that Jish had strong commercial ties with the nearby city of Tyre. On Jish's western slope, a mausoleum was excavated, with stone sarcophagi similar to those seen at the large Jewish catacomb at Beit She'arim. The inner part of the mausoleum contained ten hewn loculi, burial niches known in Hebrew as kokhim. In the mausoleum, archaeologists found several skeletons, oil lamps and a glass bottle dating to the fourth century CE.

A network of secret caves and passageways in Jish, some of them located under private homes, is strikingly similar to hideaways in the Judean lowlands used during the Bar Kokhba revolt.[51]

See also

References

- "Population in the Localities 2019" (XLS). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- Palmer, 1881, p. 76

- Conder and Kitchener, 1881, SWP I, p. 225

- Yoav Stern (30 July 2007). "Galilee villages launch campaign to attract Christian pilgrims". Haaretz. Retrieved 2007-12-19.

- YNET On the slopes of a hill, at an elevation of 860 meters surrounded by cherry orchards, pears and apples, built houses, especially church building looks from afar. Number of inhabitants 3,000 divided by 55% Maronite Christian, 30% Greek Catholics and the rest are Muslims.

- "Population" (in Hebrew). Jish local council. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- Projects - Preservation

- Encyclopedia Judaica, Jerusalem, 1978, "Giscala," vol. 7, 590

- Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 176

- Morris, 2004, p. 508

- "The Aramaic language is being resurrected in Israel". Vatican Insider - La Stampa. 24 September 2011. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- Hulot & Rabot, "Actes de la societé géographie," Seance du 6 décembre 1907, La Géographie, Volume 17, Paris, 1908, page 78

- Elizabeth A. Livingstone (1989). Papers Presented to the Tenth International Conference on Patristic Studies Held in Oxford, 1987: Historica, theologica, gnostica, Biblica et Apocrypha. Peeters Publishers. p. 63. ISBN 978-90-6831231-7. ISBN 90-6831-231-6.

- The Guide to Israel, Zev Vilnay, Jerusalem, 1972, p. 539.

- The Mishnah, (ed.) Herbert Danby, Arakhin 9:6 (p. 553 - note 9)

- el-Jish/Gush Halav

- Machen, John Gresham (1921). The Origin of Paul's Religion. New York: The MacMillan Company. p. 44. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- Jerome. "5. Paul". De Viris Illustribus [On Illustrious Men]. Translated by Richardson, Ernest Cushing. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

Paul...was of the tribe of Benjamin and the town of Giscalis in Judea. When this was taken by the Romans he removed with his parents to Tarsus in Cilicia.

- Jerome. Commentaria in Epistolam ad Philemonem [Commentary on the Epistle to Philemon] (in Latin). Retrieved 1 May 2019.

Aiunt parentes apostoli Pauli de Gyscalis regione fuisse Iudaeae

- Redefining ancient borders: The Jewish scribal framework of Matthew's Gospel, Aaron M. Gale

- Excavations at the ancient synagogue of Gush Ḥalav, Eric M. Meyers, Carol L. Meyers, James F. Strange

- The missing century: Palestine in the fifth century: growth and decline, Zeev Safrai

- Eliya Ribak (2007). Religious Communities in Byzantine Palestina. BAR International Series 1646. Oxford: Archaeopress. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-4073-0080-1.

- Hachlili, Rachel (2013). "Dating of the Upper Galilee Synagogues". Ancient Synagogues - Archaeology and Art: New Discoveries and Current Research. Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 1, Ancient Near East; vol. 105 = Handbuch der Orientalistik. BRILL. pp. 586, 588. ISBN 978-90-04-25772-6. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- Al-Muqaddasi. Description of Syria. Translated by Le Strange, Guy. p. 32.

- A. Asher (c. 1840). The Itinerary of Rabbi Benjamin of Tudela. 1. NY: Hakesheth. p. 82. This passage is not present in the edition of M. N. Adler (1907). The Itinerary of Benjamin of Tudela. London: Oxford University Press. p. 29.

- Note that Rhode, 1979, p. 6 writes that the register that Hütteroth and Abdulfattah studied was not from 1595/6, but from 1548/9

- Stephan H. Stephan (1935). "Evliya Tshelebi's Travels in Palestine, II". The Quarterly of the Department of Antiquities in Palestine. 4: 154–164.

- Damage Caused By Landslides During the Earthquakes of 1837 and 1927 in the Galilee Region

- Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol. 3. pp. 368-369

- Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, 2nd appendix, p. 134

- Conder and Kitchener, 1881, SWP I, p. 198

- Schumacher, 1888, p. 189

- Barron, 1923, Table XI, Sub-district of Safad, p. 41

- Barron, 1923, Table XVI, p. 51

- Mills, 1932, p. 107

- Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 09

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 70

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 119

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 169

- Morris, 2004, p. 473

- Morris, 2004, pp. 500–501

- Morris, 2004, p. 481, citing Israeli sources but noting their lack of clarity

- Gelber, 2001, p.226

- Morris, 2008, p. 345

- Elias Chacour; David Hazard (2003). Blood Brothers. Chosen Books. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-8007-9321-0. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- Morris, 1993, p. 167

- Galilee Coexistence Trail Inaugurated, Jerusalem Post

- Galilee villages launch campaign to attract Christian pilgrims

- Gush Halav

- ERETZ Magazine

Bibliography

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 1. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Gelber, Y. (2001), Palestine 1948, Sussex Academic Press

- Getzov, Nimrod (2010-12-23). "Gush Halav Final Report" (122). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Guérin, V. (1880). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). 3: Galilee, pt. 2. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale. (p. 94 ff)

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Hartal, Moshe (2006-09-06). "Gush Halav (A) Final Report" (118). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Hartal, Moshe (2006-11-09). "Gush Halav (B) Final Report" (118). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Hartal, Moshe (2006-11-19). "Gush Halav (C) Final Report" (118). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (1993). Israel's Border Wars, 1949 - 1956. Arab Infiltration, Israeli Retaliation, and the Countdown to the Suez War. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-827850-0.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Mukaddasi (1886). Description of Syria, including Palestine. London: Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Rhode, H. (1979). Administration and Population of the Sancak of Safed in the Sixteenth Century (PhD). Columbia University.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Schumacher, G. (1888). "Population list of the Liwa of Akka". Quarterly statement - Palestine Exploration Fund. 20: 169–191.

- Stephan, Stephan H. (1937). "Evliya Tshelebi's Travels in Palestine, IV". The Quarterly of the Department of Antiquities in Palestine. 6: 84–97.

External links

- Official website

- Gush HaLav at the Jewish Virtual Library

- Welcome To Jish (Gush Halav)

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 4: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Gush Halav Synagogue