Giant musk turtle

The giant musk turtle (Staurotypus salvinii) , also known commonly as the Chiapas giant musk turtle or the Mexican giant musk turtle , is a species of turtle in the family Kinosternidae. The species is endemic to Central America.

| Giant musk turtle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Staurotypus salvinii in an aquarium | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Family: | Kinosternidae |

| Genus: | Staurotypus |

| Species: | S. salvinii |

| Binomial name | |

| Staurotypus salvinii Gray, 1864 | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Geographic range

S. salvinii is found in Belize, El Salvador, Guatemala, western Honduras, and Mexico (Chiapas and Oaxaca).[2]

Habitat

The giant musk turtle prefers to inhabit slow-moving bodies of freshwater such as reservoirs, and rivers with soft bottoms and ample vegetation.[3]

Etymology

The specific name, salvinii, is in honor of English naturalist and herpetologist Osbert Salvin.[4]

Description

S. salvinii is typically much larger than other species of Kinosternidae, attaining a straight carapace length of up to 38 cm (15 inches), with males being significantly smaller than females. It is typically brown, black, or green in color, with a yellow underside. The carapace is distinguished by three distinct ridges, or keels which run its length. The giant musk turtle tends to be quite aggressive, agile and energetic.[2]

Diet

Like other musk turtle species, S. salvinii is carnivorous, eating various species of fishes, crustaceans, smaller turtles, insects, mollusks, and carrion. The giant musk turtle's feeding technique is to open its mouth rapidly leading to a powerful inrush of water which sucks the prey into its mouth.[2]

Reproduction

References

- Fritz, Uwe; Havaš, Peter (2007). "Checklist of Chelonians of the World" (PDF). Vertebrate Zoology. 57 (2): 260–261. ISSN 1864-5755. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-12-17. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- Bonin, Franck; Devaux, Bernard; Dupré, Alain (2006). Turtles of the World. (Translated by Peter C. H. Pritchard). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. 416 pp. ISBN 978-0801884962.

- Ernst, Carl H.; Barbour, Roger W. (1989). Turtles of the World. Washington, District of Columbia: Smithsonian Institution Press. 313 pp. ISBN 978-1560982128.

- Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. (Staurotypus salvinii, p. 232.)

- Species Staurotypus salvinii at The Reptile Database www.reptile-database.org.

External links

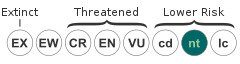

- Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group (1996). Staurotypus salvinii . 2006 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on 29 July 2007.

Further reading

- Gray JE (1864). "Description of a New Species of Staurotypus (S. salvinii ) from Guatemala". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 1864: 127–128.