Geoid

The geoid (/ˈdʒiːɔɪd/) is the shape that the ocean surface would take under the influence of the gravity and rotation of Earth alone, if other influences such as winds and tides were absent. This surface is extended through the continents (such as with very narrow hypothetical canals). According to Gauss, who first described it, it is the "mathematical figure of the Earth", a smooth but irregular surface whose shape results from the uneven distribution of mass within and on the surface of Earth. It can be known only through extensive gravitational measurements and calculations. Despite being an important concept for almost 200 years in the history of geodesy and geophysics, it has been defined to high precision only since advances in satellite geodesy in the late 20th century.

| Geodesy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Fundamentals |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Concepts |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Technologies

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Standards (history)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

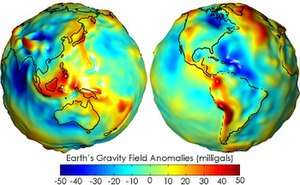

All points on a geoid surface have the same effective potential (the sum of gravitational potential energy and centrifugal potential energy). The force of gravity acts everywhere perpendicular to the geoid, meaning that plumb lines point perpendicular and water levels parallel to the geoid if only gravity and rotational acceleration were at work. The surface of the geoid is higher than the reference ellipsoid wherever there is a positive gravity anomaly (mass excess) and lower than the reference ellipsoid wherever there is a negative gravity anomaly (mass deficit).[1]

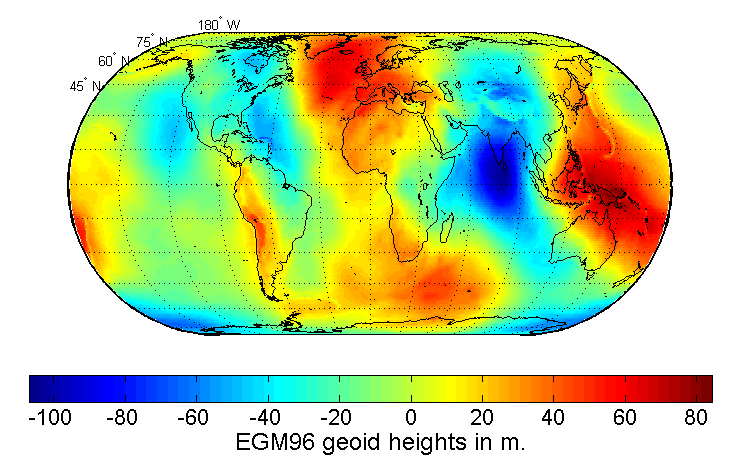

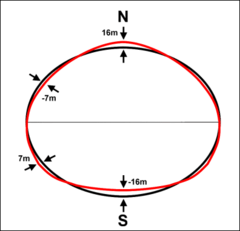

Description

The geoid surface is irregular, unlike the reference ellipsoid (which is a mathematical idealized representation of the physical Earth), but is considerably smoother than Earth's physical surface. Although the physical Earth has excursions of +8,848 m (Mount Everest) and −11,034 m (Marianas Trench), the geoid's deviation from an ellipsoid ranges from +85 m (Iceland) to −106 m (southern India), less than 200 m total.[2]

If the ocean were isopycnic (of constant density) and undisturbed by tides, currents or weather, its surface would resemble the geoid. The permanent deviation between the geoid and mean sea level is called ocean surface topography. If the continental land masses were crisscrossed by a series of tunnels or canals, the sea level in those canals would also very nearly coincide with the geoid. In reality, the geoid does not have a physical meaning under the continents, but geodesists are able to derive the heights of continental points above this imaginary, yet physically defined, surface by spirit leveling.

Being an equipotential surface, the geoid is, by definition, a surface to which the force of gravity is everywhere perpendicular. That means that when traveling by ship, one does not notice the undulations of the geoid; the local vertical (plumb line) is always perpendicular to the geoid and the local horizon tangential to it. Likewise, spirit levels will always be parallel to the geoid.

On a long voyage, spirit leveling indicates height variations even though the ship is always at sea level (neglecting the effects of tides). That is because GPS satellites, orbiting about the center of gravity of the Earth, can measure heights only relative to a geocentric reference ellipsoid. To obtain one's geoidal height, a raw GPS reading must be corrected. Conversely, height determined by spirit leveling from a tidal measurement station, as in traditional land surveying, is always geoidal height. Modern GPS receivers have a grid implemented in the source of the geoid (e.g. EGM-96) height over the World Geodetic System (WGS) ellipsoid from the current position. Then, they are able to correct the height above WGS ellipsoid to the height above EGM96 geoid. When height is not zero on a ship, the discrepancy is caused by other factors such as ocean tides, atmospheric pressure (meteorological effects) and local sea surface topography.

Simplified example

The gravitational field of the earth is not uniform. An oblate spheroid is typically used as the idealized earth, but even if the earth were perfectly spherical, the strength of gravity would not be the same everywhere, because density (and therefore mass) varies throughout the planet. This is due to magma distributions, mountain ranges, deep sea trenches, and so on.

If that perfect sphere were then covered in water, the water would not be the same height everywhere. Instead, the water level would be higher or lower depending on the particular strength of gravity in that location.

Undulation

Undulation of the geoid is the height of the geoid relative to a given ellipsoid of reference. The undulation is not standardized, as different countries use different mean sea levels as reference, but most commonly refers to the EGM96 geoid.

Relationship to GPS/GNSS

In maps and common use the height over the mean sea level (such as orthometric height) is used to indicate the height of elevations while the ellipsoidal height results from the GPS system and similar GNSS.

The deviation between the ellipsoidal height and the orthometric height can be calculated by

Likewise, the deviation between the ellipsoidal height and the normal height can be calculated by

Spherical harmonics representation

Spherical harmonics are often used to approximate the shape of the geoid. The current best such set of spherical harmonic coefficients is EGM96 (Earth Gravity Model 1996),[4] determined in an international collaborative project led by the National Imagery and Mapping Agency (now the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, or NGA). The mathematical description of the non-rotating part of the potential function in this model is:[5]

where and are geocentric (spherical) latitude and longitude respectively, are the fully normalized associated Legendre polynomials of degree and order , and and are the numerical coefficients of the model based on measured data. Note that the above equation describes the Earth's gravitational potential , not the geoid itself, at location the co-ordinate being the geocentric radius, i.e., distance from the Earth's centre. The geoid is a particular equipotential surface,[5] and is somewhat involved to compute. The gradient of this potential also provides a model of the gravitational acceleration. EGM96 contains a full set of coefficients to degree and order 360 (i.e. ), describing details in the global geoid as small as 55 km (or 110 km, depending on your definition of resolution). The number of coefficients, and , can be determined by first observing in the equation for V that for a specific value of n there are two coefficients for every value of m except for m = 0. There is only one coefficient when m=0 since . There are thus (2n+1) coefficients for every value of n. Using these facts and the formula, , it follows that the total number of coefficients is given by

- using the EGM96 value of .

For many applications the complete series is unnecessarily complex and is truncated after a few (perhaps several dozen) terms.

New even higher resolution models are currently under development. For example, many of the authors of EGM96 are working on an updated model that should incorporate much of the new satellite gravity data (e.g., the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment), and should support up to degree and order 2160 (1/6 of a degree, requiring over 4 million coefficients).[6]

The NGA has announced the availability of EGM2008, complete to spherical harmonic degree and order 2159, and contains additional coefficients extending to degree 2190 and order 2159.[7] Software and data is on the Earth Gravitational Model 2008 (EGM2008) - WGS 84 Version] page.[7]

Determination

Calculating the undulation is mathematically challenging.[8][9] This is why many handheld GPS receivers have built-in undulation lookup tables[10] to determine the height above sea level.

The precise geoid solution by Vaníček and co-workers improved on the Stokesian approach to geoid computation.[11] Their solution enables millimetre-to-centimetre accuracy in geoid computation, an order-of-magnitude improvement from previous classical solutions.[12][13][14][15]

Geoid undulations display uncertainties which can be estimated by using several methods, e.g. least-squares collocation (LSC), fuzzy logic, artificial neutral networks, radial basis functions (RBF), and geostatistical techniques. Geostatistical approach has been defined as the most improved technique in prediction of geoid undulation.[16]

Anomalies

Variations in the height of the geoidal surface are related to density anomalous distributions within the Earth. Geoid measures thus help understanding the internal structure of the planet. Synthetic calculations show that the geoidal signature of a thickened crust (for example, in orogenic belts produced by continental collision) is positive, opposite to what should be expected if the thickening affects the entire lithosphere. Mantle convection also changes the shape of the geoid over time.[17]

Time-variability

Recent satellite missions, such as the Gravity Field and Steady-State Ocean Circulation Explorer (GOCE) and GRACE, have enabled the study of time-variable geoid signals. The first products based on GOCE satellite data became available online in June 2010, through the European Space Agency (ESA)’s Earth observation user services tools.[18][19] ESA launched the satellite in March 2009 on a mission to map Earth's gravity with unprecedented accuracy and spatial resolution. On 31 March 2011, the new geoid model was unveiled at the Fourth International GOCE User Workshop hosted at the Technische Universität München in Munich, Germany.[20] Studies using the time-variable geoid computed from GRACE data have provided information on global hydrologic cycles,[21] mass balances of ice sheets,[22] and postglacial rebound.[23] From postglacial rebound measurements, time-variable GRACE data can be used to deduce the viscosity of Earth's mantle.[24]

Other celestial bodies

The concept of the geoid has been extended to other planets and also moons,[25] as well as asteroids.

The areoid (the geoid of Mars)[26] has been measured using flight paths of satellite missions such as Mariner 9 and Viking. The main departures from the ellipsoid expected of an ideal fluid are from the Tharsis volcanic plateau, a continent-size region of elevated terrain, and its antipodes.[27]

See also

- Geodetic datum

- Geopotential

- Physical geodesy

- International Terrestrial Reference Frame

References

- Fowler, C.M.R. (2005). The Solid Earth; An Introduction to Global Geophysics. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 214. ISBN 9780521584098.

- "Earth's Gravity Definition". GRACE - Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment. Center for Space Research (University of Texas at Austin) / Texas Space Grant Consortium. 11 February 2004. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- "WGS 84, N=M=180 Earth Gravitational Model". NGA: Office of Geomatics. National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- "DoD World Geodetic System 1984". NGA: Office of Geomatics. National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- Smith, Dru A. (1998). "There is no such thing as "The" EGM96 geoid: Subtle points on the use of a global geopotential model". IGeS Bulletin No. 8. Milan, Italy: International Geoid Service. pp. 17–28. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- Pavlis, N.K., S.A. Holmes. S. Kenyon, D. Schmit, R. Trimmer, "Gravitational potential expansion to degree 2160", IAG International Symposium, gravity, geoid and Space Mission GGSM2004, Porto, Portugal, 2004.

- "Earth Gravitational Model 2008 (EGM2008)". nga.mil.

- Sideris, Michael G. (2011). "Geoid Determination, Theory and Principles". Encyclopedia of Solid Earth Geophysics. Encyclopedia of Earth Sciences Series. pp. 356–362. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-8702-7_154. ISBN 978-90-481-8701-0.

- Sideris, Michael G. (2011). "Geoid, Computational Method". Encyclopedia of Solid Earth Geophysics. Encyclopedia of Earth Sciences Series. pp. 366–371. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-8702-7_225. ISBN 978-90-481-8701-0.

- Wormley, Sam. "GPS Orthometric Height". www.edu-observatory.org. Archived from the original on 20 June 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- "UNB Precise Geoid Determination Package". Retrieved 2 October 2007.

- Vaníček, P.; Kleusberg, A. (1987). "The Canadian geoid-Stokesian approach". Manuscripta Geodaetica. 12 (2): 86–98.

- Vaníček, P.; Martinec, Z. (1994). "Compilation of a precise regional geoid" (PDF). Manuscripta Geodaetica. 19: 119–128.

- P., Vaníček; A., Kleusberg; Z., Martinec; W., Sun; P., Ong; M., Najafi; P., Vajda; L., Harrie; P., Tomasek; B., ter Horst. Compilation of a Precise Regional Geoid (PDF) (Report). Department of Geodesy and Geomatics Engineering, University of New Brunswick. 184. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- Kopeikin, Sergei; Efroimsky, Michael; Kaplan, George (2009). Relativistic celestial mechanics of the solar system. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. p. 704. ISBN 9783527408566.

- Chicaiza, E.G.; Leiva, C.A.; Arranz, J.J.; Buenańo, X.E. (14 June 2017). "Spatial uncertainty of a geoid undulation model in Guayaquil, Ecuador". Open Geosciences. 9 (1): 255–265. Bibcode:2017OGeo....9...21C. doi:10.1515/geo-2017-0021. ISSN 2391-5447.

- Richards, M. A., and B. H. Hager, 1984. Geoid anomalies in a dynamic mantle, J. Geophys. Res., 89, 5987–6002, doi:10.1029/JB089iB07p05987.

- "ESA makes first GOCE dataset available". GOCE. European Space Agency. 9 June 2010. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- "GOCE giving new insights into Earth's gravity". GOCE. European Space Agency. 29 June 2010. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- "Earth's gravity revealed in unprecedented detail". GOCE. European Space Agency. 31 March 2011. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- Schmidt, R; Schwintzer, P; Flechtner, F; Reigber, C; Guntner, A; Doll, P; Ramillien, G; Cazenave, A; et al. (2006). "GRACE observations of changes in continental water storage". Global and Planetary Change. 50 (1–2): 112–126. Bibcode:2006GPC....50..112S. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2004.11.018.

- Ramillien, G; Lombard, A; Cazenave, A; Ivins, E; Llubes, M; Remy, F; Biancale, R (2006). "Interannual variations of the mass balance of the Antarctica and Greenland ice sheets from GRACE". Global and Planetary Change. 53 (3): 198. Bibcode:2006GPC....53..198R. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2006.06.003.

- Vanderwal, W; Wu, P; Sideris, M; Shum, C (2008). "Use of GRACE determined secular gravity rates for glacial isostatic adjustment studies in North-America". Journal of Geodynamics. 46 (3–5): 144. Bibcode:2008JGeo...46..144V. doi:10.1016/j.jog.2008.03.007.

- Paulson, Archie; Zhong, Shijie; Wahr, John (2007). "Inference of mantle viscosity from GRACE and relative sea level data". Geophysical Journal International. 171 (2): 497. Bibcode:2007GeoJI.171..497P. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2007.03556.x.

- Wieczorek, M. A. (2007). "Gravity and Topography of the Terrestrial Planets". Treatise on Geophysics. pp. 165–206. doi:10.1016/B978-044452748-6.00156-5. ISBN 9780444527486.

- Ardalan, A. A.; Karimi, R.; Grafarend, E. W. (2009). "A New Reference Equipotential Surface, and Reference Ellipsoid for the Planet Mars". Earth, Moon, and Planets. 106 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1007/s11038-009-9342-7. ISSN 0167-9295.

- Cattermole, Peter (1992). Mars The story of the Red Planet. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. p. 185. ISBN 9789401123068.

Further reading

- H. Moritz (2011). "A contemporary perspective of geoid structure". Journal of Geodetic Science. Versita. 1 (March): 82–87. Bibcode:2011JGeoS...1...82M. doi:10.2478/v10156-010-0010-7.

- "CHAPTER V PHYSICAL GEODESY". www.ngs.noaa.gov. NOAA. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

External links

| Look up geoid in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Main NGA (was NIMA) page on Earth gravity models

- International Geoid Service (IGeS)

- EGM96 NASA GSFC Earth gravity model

- Earth Gravitational Model 2008 (EGM2008, Released in July 2008)

- NOAA Geoid webpage

- International Centre for Global Earth Models (ICGEM)

- Kiamehr's Geoid Home Page

- Geoid tutorial from Li and Gotze (964KB pdf file)

- Geoid tutorial at GRACE website

- Precise Geoid Determination Based on the Least-Squares Modification of Stokes’ Formula(PhD Thesis PDF)