Cockfight

A cockfight is a blood sport between two cocks, or gamecocks, held in a ring called a cockpit. The history of raising fowl for fighting goes back 6,000 years. The first documented use of the word gamecock, denoting use of the cock as to a "game", a sport, pastime or entertainment, was recorded in 1634,[1] after the term "cock of the game" used by George Wilson, in the earliest known book on the sport of cockfighting in The Commendation of Cocks and Cock Fighting in 1607. But it was during Magellan's voyage of discovery of the Philippines in 1521 when modern cockfighting was first witnessed and documented by Antonio Pigafetta, Magellan's chronicler, in the kingdom of Taytay.

.jpg)

The combatants, referred to as gamecocks (not to be confused with game birds), are specially bred and conditioned for increased stamina and strength. Male and female chickens of such a breed are referred to as game fowl. Cocks possess congenital aggression toward all males of the same species. Wagers are often made on the outcome of the match.

Cockfighting is a blood sport due in some part to the physical trauma the cocks inflict on each other, which is sometimes increased by attaching metal spurs to the cocks' natural spurs. While not all fights are to the death, the cocks may endure significant physical trauma. In some areas around the world, cockfighting is still practiced as a mainstream event; in some countries it is regulated by law, or forbidden outright. Advocates of the "age old sport"[2][3] often list cultural and religious relevance as reasons for perpetuation of cockfighting as a sport.[4]

Process

Two owners place their gamecock in the cockpit. The cocks fight until ultimately one of them dies or is critically injured. Historically, this was in a cockpit, a term which was also used in the 16th century to mean a place of entertainment or frenzied activity. William Shakespeare used the term in Henry V to specifically mean the area around the stage of a theatre. In Tudor times, the Palace of Westminster had a permanent cockpit, called the Cockpit-in-Court.

History

Cockfighting is an ancient spectator sport. There is evidence that cockfighting was a pastime in the Indus Valley Civilization.[5] The Encyclopædia Britannica (2008) holds:[6]

The sport was popular in ancient times in India, China, Persia, and other Eastern countries and was introduced into Ancient Greece in the time of Themistocles (c. 524–460 BC). For a long time the Romans affected to despise this "Greek diversion", but they ended up adopting it so enthusiastically that the agricultural writer Columella (1st century AD) complained that its devotees often spent their whole patrimony in betting at the side of the pit.

Based on his analysis of a Mohenjo-daro seal, Iravatham Mahadevan speculates that the city's ancient name could have been Kukkutarma ("the city [-rma] of the cockerel [kukkuta]").[7][8] However, according to a recent study,[9] "it is not known whether these birds made much contribution to the modern domestic fowl. Chickens from the Harappan culture of the Indus Valley (2500–2100 BC) may have been the main source of diffusion throughout the world." "Within the Indus Valley, indications are that chickens were used for sport and not for food" (Zeuner 1963)[10] and that by 1000 BC they had assumed "religious significance".[10]

Some additional insight into the pre-history of European and American secular cockfighting may be taken from The London Encyclopaedia:

At first cockfighting was partly a religious and partly a political institution at Athens; and was continued for improving the seeds of valor in the minds of their youth, but was afterwards perverted both there and in the other parts of Greece to a common pastime, without any political or religious intention.[11]

An early image of a fighting rooster has been found on a 6th-century BC seal of Jaazaniah from the biblical city of Mizpah in Benjamin, near Jerusalem.[12][13] Remains of these birds have been found at other Israelite Iron Age sites, when the rooster was used as a fighting bird; they are also pictured on other seals from the period as a symbol of ferocity, such as the late-7th-century BC red jasper seal inscribed "Jehoahaz, son of the king",[14][15] which likely belonged to Jehoahaz of Judah "while he was still a prince during his father's life".[16]

The anthropologist Clifford Geertz wrote the influential essay Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight, on the meaning of the cockfight in Balinese culture.

.jpg)

Regional variations

In some regional variations, the birds are equipped with either metal spurs (called gaffs) or knives, tied to the leg in the area where the bird's natural spur has been partially removed. A cockspur is a bracelet (often made of leather) with a curved, sharp spike which is attached to the leg of the bird. The spikes typically range in length from "short spurs" of just over an inch to "long spurs" almost two and a half inches long. In the highest levels of 17th century English cockfighting, the spikes were made of silver. The sharp spurs have been known to injure or even kill the bird handlers.[18] In the naked heel variation, the bird's natural spurs are left intact and sharpened: fighting is done without gaffs or taping, particularly in India (especially in Tamil Nadu). There it is mostly fought naked heel and either three rounds of twenty minutes with a gap of again twenty minutes or four rounds of fifteen minutes each and a gap of fifteen minutes between them.[19]

Cockfighting is common throughout Southeast Asia, where it is implicated in spreading bird flu.[20][21] Cockfighting is a popular form of fertility worship in Southeast Asia.[22]

India

Cockfighting (Kodi Pandem in Telugu) (Kori katta in Tulu) (Vetrukkaal seval porr in Tamil which means "naked heel cockfight") is a favourite sport of people living in the coastal region of Andhra Pradesh, Dakshina Kannada and Udupi districts of Tulu Nadu region of Karnataka, and the state of Tamil Nadu, India. Three- or four-inch blades (Bal in Tulu) are attached to the cocks' legs. Knockout fights to the death are widely practised in Andhra Pradesh. In Tamil Nadu, the winner is decided after three or four rounds. People watch with intense interest surrounding the cocks. The sport has gradually become a gambling sport.

In Jharkhand the cockfighting game is known as "pada", the spurs are called "kant", the cockpit is called "chhad", and the person in the cockpit or who ties the spurs is called "kantkar".

In the Tamil Nadu districts of Chennai, Tanjore, Trichy and Salem, only the 'naked heel' variation is permitted. In Erode, Thiruppur, Karur and Coimbatore districts, only bloody blade fights are conducted. During festival seasons, this is the major game for men. Women normally don't participate. Only the Pure breeds are chosen to the fight. Naked heel cocks Fight for long duration compared with Blade fight cocks.[23]

The cockfight, or more accurately expressed the secular cockfight, is an intense sport, recreation, or pastime to some, while to others, the cockfight remains an ancient religious ritual, a sacred ceremony (i.e. a religious and spiritual cockfight) associated with the ‘daivasthanams’ (temples) and held at the temples precincts.[24] In January 2012 at India's 'Sun God' Festival the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) district committee, demanded that police not interfere in the cockfighting known as ‘kozhi kettu’ as it is a part of the temple rituals.[25]

Indonesia

Cockfighting is a very old tradition in Balinese Hinduism, the Batur Bang Inscriptions I (from the year 933) and the Batuan Inscription (dated 944 on the Balinese Caka calendar) disclose that the tabuh rah ritual has existed for centuries.[26]

In Bali, cockfights, known as tajen, are practiced in an ancient religious purification ritual to expel evil spirits.[27] This ritual, a form of animal sacrifice, is called tabuh rah ("pouring blood").[28] The purpose of tabuh rah is to provide an offering (the blood of the losing chicken) to the evil spirits. Cockfighting is a religious obligation at every Balinese temple festival or religious ceremony.[29] Cockfights without a religious purpose are considered gambling in Indonesia, although it is still largely practiced in many parts of Indonesia. Women are generally not involved in the tabuh rah process. The tabuh rah process is held on the largest pavilion in a Balinese temple complex, the wantilan.

The American anthropologist Clifford Geertz published his most famous work, Notes on the Balinese Cockfight, on the practice of cockfights in Bali. In it, he argued that the cockfight served as a pastiche or model of wider Balinese society from which judgments about other aspects of the culture could be drawn.

Philippines

Cockfighting, locally termed sabong, is a popular pastime in the Philippines, where both illegal and legal cockfights occur. Legal cockfights are held in cockpits every week, whilst illegal ones, called tupada or tigbakay, are held in secluded cockpits where authorities cannot raid them. In both types, knives or gaffs are used. There are two kinds of knives used in Philippine cockfighting: single-edged blades (used in derbies) and double-edged blades; lengths of knives also vary. All knives are attached on the left leg of the bird, but depending on agreement between owners, blades can be attached on the right or even on both legs. Sabong and illegal tupada, are judged by a referee called sentensyador or koyme, whose verdict is final and not subject to any appeal.[30] Bets are usually taken by the kristo, so named because of his outstretched hands when calling out wagers from the audience and skillfully doing so purely from memory.

The country has hosted several World Slasher Cup derbies, held biannually at the Smart Araneta Coliseum, Quezon City, where the world's leading game fowl breeders gather. World Slasher Cup is also known as the "Olympics of Cockfighting". The World Gamefowl Expo 2014 was held in the World Trade Center Metro Manila.

Cockfighting was already flourishing in pre-colonial Philippines, as recorded by Antonio Pigafetta, the Italian diarist aboard Ferdinand Magellan’s 1521 expedition.[31] Cockfighting in the Philippines is derived from the fact that it shares elements of Indian and other Southeast Asian cultures, where the jungle fowl (bankivoid) and Oriental type of chicken are endemic.

Other bird species

Male saffron finches[32] and canaries have been used in fights on occasion.[33]

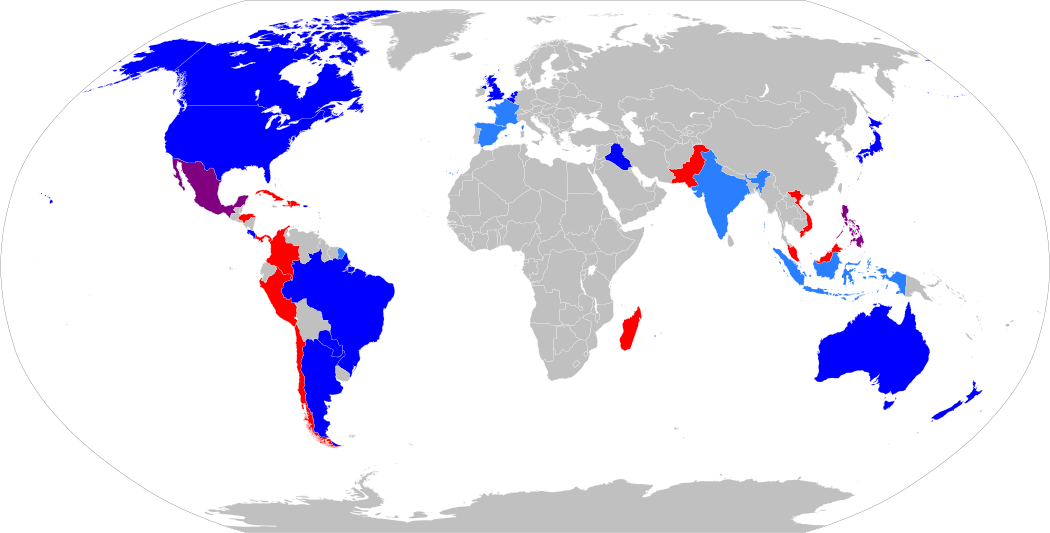

Legal status

Argentina

Article 3.8 of Law 14.346 on the Ill-Treatment and Acts of Cruelty to Animals of 1954 explicitly prohibits 'carrying out public or private acts of animal fights, fights of bulls and heifers, or parodies [thereof], in which animals are killed, wounded or harassed.'[34]

Australia

Cockfighting, and the possession of cockfighting equipment, is illegal in Australia.[35][36]

Belgium

In Belgium, cockfights have been prohibited in 1867. In 1929 all organised fights between animals were banned. In 1986 and 1991, the animal welfare act was amended by also criminalising attendance of cockfights. Offenders risk six months imprisonment and a fine of 2,000 euros. Since the 1990s, several people have been prosecuted for cockfighting.[37]

Brazil

Cockfighting (rinha de galos) was banned in 1934 with the help of President Getúlio Vargas through Brazil's 1934 constitution, passed on 16 July. Based on the recognition of animals in the Constitution, a Brazilian Supreme Court ruling resulted in the ban of animal related activities that involve claimed "animal suffering such as cockfighting, and a tradition practiced in southern Brazil, known as 'Farra do Boi' (the Oxen Festival)",[38] stating that "animals also have the right to legal protection against mistreatment and suffering".[39]

Chile

Chilean Law no. 20.380 on Animal Protection of 25 August 2009 explicitly exempts various forms of 'animal sports' in Article 16: 'The norms of this law will not apply to sports in which animals participate, such as rodeo, cowfights, movement to the rein and equestrian sports, which will be governed by their respective regulations.'[40]

Colombia

In Colombia, cockfighting is a tradition, especially in the Caribbean region and in some areas of the Andean interior. Cockfights are held during the Festival de la Leyenda Vallenata in Valledupar. In August 2010, the Constitutional Court of Colombia rejected a lawsuit that sought to prohibit bullfighting, corralejas and cockfighting with the argument that they constitute animal abuse. In March 2019, the same court confirmed such rule, under the argument that cockfighing and bullfighting are traditions with cultural roots in some municipalities of the country.[41] The Asociación Nacional de Criadores de Gallos de Pelea organizes an international cockfighting championship.[42]

Cockfighting was immortalized in the novel One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez, in episodes such as the events that led to the death of Prudencio Aguilar, or the fondness for it by José Arcadio Segundo. Cockfighting was one of the main subjects of La Caponera, a TV adaptation of Juan Rulfo's novel, El gallo de oro, aired in Colombia and other countries in the region during the late 90s.

Costa Rica

Cockfights have been illegal in Costa Rica since 1922.[43] The government deems the activity as animal cruelty, public disorder and a risk for public health and is routinely repressed by the State's National Secretary for Animal Welfare.[44] The activity is also rejected by most of the population, as 88% of Costa Ricans dislike cockfights according to recent polls of the National University.[45] Since 2017, the activity is punishable with up to two years of prison.[46]

Cuba

In Cuba, cockfighting is legal and popular, although gambling on matches has been banned since the 1959 Revolution.[47][48] The state has opened official arenas, including a 1,000-seat venue in Ciego de Ávila, but there are also banned underground cockfighting pits.[48]

Cockfighting was so common during the Cuban colonization by Spain that there were arenas in every urban and rural town. The first official known document about cockfighting in Cuba dates from 1737. It is a royal decree asking, to the governor of the island, a report about the inconveniences that might cause cockfights "with the people from land and sea" and asking for information about rentals of the games. The Spaniard Miguel Tacón, Lieutenant General and governor of the colony, banned cockfighting by a decree dated on October 20, 1835, limiting these spectacles only to holidays.

In 1844, a decree dictated by the Captain General of the island, Leopoldo O'Donnell, forbade to non-white people the attendance to these shows. During the second half of the 19th century, many authorizations were conceded for building arenas, until General Juan Rius Rivera, then civilian governor in Havana, prohibited cockfighting by a decree of October 31, 1899, and later the Cuban governor, General Leonard Wood, dictated the military order no. 165 prohibiting cockfights in the whole country since June 1, 1900.[49]

In the first half of the 20th century, legality of cockfights suffered several ups and downs.[50]

In 1909, the then-Cuban president José Miguel Gómez, with the intention to gain followers, allowed cockfights once again, and then regulations were agreed for the fights.[51]

Up to the beginning of 1968, cockfights used to be held everywhere in the country, but with the purpose of stopping the bets, the arenas were closed and the fights forbidden by the authorities. In 1980, authorities legalized cockfights again and a state business organization was created with the participation of the private breeders, grouped in territories. Every year the state organization announces several national tournaments from January to April, makes trade shows and sells fighting cocks to clients from other Caribbean countries.[49]

Dominican Republic

In the Dominican Republic, cockfighting is legal, but according to Dominican Today 'increasingly rejected by society' as of December 2018.[52] There is at least one arena (gallera) in every town, whereas in bigger cities larger coliseos can be found. Important fights are broadcast on television and newspapers have dedicated pages to cockfights and the different trabas, the local name for gamefowl breeding grounds. Those dedicated to the breeding and training of fighting cocks are called galleros or traberos. The cocks are often outfitted with special spurs made from various materials (ranging from plastic to metal or even carey shell) and fights are typically to the death. Public perception of the sport is as normal as that of baseball or any other major sport.

France

Holding cockfights is a crime in France, but there is an exemption under subparagraph 3 of article 521–1 of the French penal code for cockfights and bullfights in locales where an uninterrupted tradition exists for them. Thus, cockfighting is allowed in the Nord-Pas de Calais region, where it takes place in a small number of towns including Raimbeaucourt, La Bistade[53] and other villages around Lille.[54] However, the construction of new cockfighting areas is prohibited, a law upheld by the Constitutional Council of France in 2015.[55]

Cockfighting is also legal in some French Overseas Territories.[55]

Haiti

Cockfighting is legal in Haiti. Nevins (2015) described it as 'the closest thing to a national sport in Haiti', being organised every Sunday morning in places across the country. Sharp spurs are attached to the roosters' feet to make them extra lethal, and the fight usually ends with the death of one of the animals.[56]

Honduras

In Honduras, under Article 11 of 'Decree no. 115-2015 ─ Animal Protection and Welfare Act' that went into effect in 2016, dog and cat fights and duck races are prohibited, while 'bullfighting shows and cockfights are part of the National Folklore and as such allowed'.[57]

India

The Supreme Court of India has banned cockfighting as a violation of the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, but it remains popular, especially in the rural coast of Andhra Pradesh, with large amount of betting involved, especially around the festival of Sankranti.[58][59][60] It is also popular in parts of Tamil Nadu.

Indonesia

All forms of gambling, including the gambling within secular cockfighting, were made illegal in 1981 by the Indonesian government, while the religious aspects of cockfighting within Balinese Hinduism remain protected. However, secular cockfighting remains widely popular in Bali, despite its illegal status.[61]

Iraq

Cockfighting is illegal but widespread in Iraq. The attendees come to gamble or just for the entertainment. A rooster can cost up to $8,000. The most-prized birds are called Harati, which means that they are of Turkish or Indian origin, and have muscular legs and necks.[62]

Japan

Cockfighting was introduced to Japan from China in the early 8th century and rose to popularity in the Kamakura period and the Edo period.[63] Cockfighting endured in some Japanese regions even after being banned in 1873,[63] during the Meiji period.[64]

Mexico

.jpg)

Cockfighting is not banned in Mexico, and practiced in the Mexican states of Michoacán, Aguascalientes, Jalisco, Sinaloa, and Veracruz, mostly during regional fairs and other celebrations. Cockfights are performed in palenques (pits).[65] Cockfighting remains legal in the municipality of Ixmiquilpan and throughout Mexico.[66]

In Mexico, cockfighting is part of the culture and traditions of most states, the two parties to the bird fights are distinguished through the colors red and green, so it is common to see a scarf or allusive badge hanging on the belt to these colors, in addition to being a business activity where the rooster show and musical shows are both combined. Almost all of the fairs and regional festivals of the country's municipalities are held in venues called "palenques" of roosters. These consist of a ring made of wood whose center is full of compacted earth for the best performance of the roosters. In the center, a box 4 meters per side and lines that cross from center to center each side are marked with lime. Finally, the last square, measuring 40 cm on each side, is marked in the center of the arena, where the roosters are taken the third time they are released. The Mexican states where cockfighting is most common are Michoacán, Aguascalientes, Jalisco, Sinaloa and Veracruz. There are only cockfight bans in the country's capital, Mexico City,[67] and in the states of Sonora and Coahuila since September 11, 2012, and in Veracruz since November 6, 2018 [68]

Netherlands

In the Netherlands, organising or attending cockfights is illegal and punishable by up to three years imprisonment, or a fine of up to 20,500 euros.[69]

New Zealand

The act of cockfighting is illegal under the Animal Welfare Act 1999, as is the possession, training and breeding of cocks for fighting.[70]

Pakistan

Cockfighting is a popular sport in rural Pakistan; however, "betting is illegal under the Prevention of Gambling Act 1977".[71] Betting is illegal, but police often turn a blind eye towards it. In Sindh (one of 4 major provinces of Pakistan), people are fond of keeping fighting cock breed, known as Sindhi aseel in Pakistan. These cocks are noted being tall, heavy and good at fighting. Another popular breed is called Mianwali Aseel. In Sindh Gamblor or Khafti uses Almond and other power enhancing medicines to feed the fighter cocks.

Panama

Law 308 on the Protection of Animals was approved by the National Assembly of Panama on 15 March 2012. Article 7 of the law states: 'Dog fights, animal races, bullfights – whether of the Spanish or Portuguese style – the breeding, entry, permanence and operation in the national territory of all kinds of circus or circus show that uses trained animals of any species, are prohibited.' However, horse racing and cockfighting were exempt from the ban.[72]

Paraguay

Organising fights between all animals, both in public and private, is prohibited in Paraguay under Law No. 4840 on Animal Protection and Welfare, promulgated on 28 January 2013. Specifically:

- 'The use of animals in shows, fights, popular festivals and other activities that imply cruelty or mistreatment, that can cause death, suffering or make them the object of unnatural and unworthy treatments' is prohibited (Article 30).

- 'Training domestic animals to carry out provoked fights, with the goal of holding a public or private show' is considered an 'act of mistreatment'. (Article 31)

- 'The use of animals in shows, fights, popular festivals, and other activities that imply cruelty or mistreatment, which may cause death, suffering or make them subject to unnatural or humiliating treatment' is considered a 'very serious infraction' (Article 32), which are punishable by between 501 and 1500 minimum daily wages (jornales mínimos, Article 39), and the perpetrator may be barred from 'acquiring or possessing other animals for a period that may be up to 10 years' (Article 38).[73]

Peru

According to the Encyclopedia of Latino Culture, Peru "has probably the longest historical tradition" with cockfighting, with the practice possibly dating back to the 16th century.[65] Cockfighting is legal and regulated by the government in Peru. Most pits (coliseos) in the country are located in Lima.[65] Cockfighting and bullfighting are exempt from Peru's animal protection laws.[74]

In October 2018, over 5,000 Peruvians signed a petition that called for a constitutional ban on "all cruel shows using animals" including cockfighting and bullfighting, which was accepted and taken into consideration by the Supreme Court of Peru. However, with only three of the five required judges agreeing with the petition, on 25 February 2020 the Court ruled that it could not declare the animal fighting practices unconstitutional, leaving the applicants with no further option of appeal. A week before the verdict, thousands of other people had marched through the streets of Lima in support of the animal fighting practices.[74]

Philippines

There is no nationwide ban of cockfighting in the Philippines but since 1948, cockfighting is prohibited every Rizal Day on December 30 where violators can be fined or imprisoned due to the Republic Act No. 229.[75]

On March 14, 2020, the Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG) announced that cockfighting is temporarily banned in the Philippines due to the prohibition of mass gatherings amid the coronavirus pandemic and community quarantines across the Philippines.[76][77]

Davao City Mayor Sara Duterte banned cockfighting in Davao City since April 16, 2020, also due to the coronavirus pandemic.[78]

Spain

Cockfighting is banned in Spain except in two Spanish regions: the Canary Islands and Andalusia. In Andalusia, however, the activity has virtually disappeared, surviving only within a program to maintain the fighting breed "combatiente español" coordinated by the University of Córdoba.[79] Spain's Animal Protection Law of 1991 recognizes an exception for these regions based on cultural heritage and a history of cockfighting in the region.[80][65] Animal rights organizations have sought to ban the bloodsport nationwide, but have not been successful in advancing legislation through the Spanish Parliament.[80]

United Kingdom

Cockfighting was banned outright in England and Wales and in the British Overseas Territories with the Cruelty to Animals Act 1835. Sixty years later, in 1895, cockfighting was also banned in Scotland, where it had been relatively common in the 18th century.[81] A reconstructed cockpit from Denbigh in North Wales may be found at St Fagans National History Museum in Cardiff[82] and a reference exists in 1774 to a cockpit at Stanecastle in Scotland.[83]

According to a 2007 report by the RSPCA, cockfighting in England and Wales was still taking place, but had declined in recent years.[84]

United States

Cockfighting is illegal in all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia. The last state to implement a state law banning cockfighting was Louisiana; the Louisiana State Legislature voted to approve a ban in June 2007,[85] which went into effect in August 2008.[86]

As of 2013:

- Cockfighting is a felony in 40 states and the District of Columbia.[87]

- The possession of birds for fighting is prohibited in 39 states and the District of Columbia.[87]

- Being a spectator at a cockfight is prohibited in 43 states and the District of Columbia.[87]

- The possession of cockfighting implements is prohibited in 15 states.[87]

Additionally, the 2014 farm bill, signed into law by President Obama, contained a provision making it a federal crime to attend an animal fighting event or bring a child under the age of 16 to an animal fighting event.[88]

The cockfighting ban was further extended by federal law to include U.S. territories—American Samoa, the Northern Mariana Islands, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands—effective at the end of 2019, as signed into law in the 2018 farm bill by President Trump.[89] In Puerto Rico, cockfighting is popular and has been considered a "national sport" since at least the 1950s.[90] According to a National Park Service report, it generates about $100 million annually. There are some 200,000 fighting birds annually on the island. Puerto Rico's Cockfighting Commission regulates 87 clubs, but many non-government sanctioned "underground" cockfighting operations exist.[91] On December 18, 2019, estimating that cockfighting employs 27,000 people and has a value to the economy of about $18 million, Puerto Rico passed a law attempting to keep the practice legal despite the imminent federal ban.[92]

The Animal Fighting Prohibition Enforcement Act, a federal law that made it a federal crime to transfer cockfighting implements across state or national borders and increasing the penalty for violations of federal animal fighting laws to three years in prison, became law in 2007. It passed the House of Representatives 368–39 and the Senate by unanimous consent and was signed into law by President George W. Bush.[93]

The Animal Welfare Act was amended again in 2008 when provisions were included in the 2008 Farm Bill (P.L. 110-246). These provisions tightened prohibitions on dog and other animal fighting activities, and increased penalties for violations of the act.[94]

Major law enforcement raids against cockfighting occurred in February 2014 in New York State (when 3,000 birds were seized and nine men were charged with felony animal-fighting in "Operation Angry Birds", the state's largest-ever cockfighting bust)[95][96][97] and in May 2017 in California (when the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department seized 7,000 cockfighting birds at a ranch in Val Verde, California, one of the largest cockfighting busts in U.S. history).[98][99] In 2014, Princess Irina of Romania pleaded guilty in federal court to operating a cockfighting ring in Oregon.[100][101]

In music

Cockfighting has also been mentioned in songs such as Kings of Leon's "Four Kicks" and Bob Dylan's song "Cry a While" from the album Love and Theft. The story song "El Gallo del Cielo" by Tom Russell is entirely about cockfighting, and the lyrics utilize detailed imagery of fighting pits, gamecocks, and gambling on the outcome of the fights. Cockfighting has also been in Korean boy band Exo's music video for "Lotto".

In visual arts

The painting The Cock Fight (1846) an academic exercise of the French painter Jean-Léon Gérôme, Vainqueur au combat de coqs (1864) bronze statue from the French sculptor Alexandre Falguière and the painting Cockfight (1882) from the Flemish painter Emile Claus are samples of the presence of cockfighting in visual arts.

The Expressionist painter Sir Robin Philipson, of Edinburgh, was well known for his series of works that included depictions of cockfighting.

The 1930 cartoon Mexico shows Oswald the Lucky Rabbit challenging a bear in a cockfight. The 1938 cartoon Honduras Hurricane features the pirate John Silver forcing Captain Katzenjammer into a rigged cockfight. Other cartoon depictions portray humanized roosters treating cockfights like boxing matches; these cartoons include Disney's Cock o' the Walk (1936), MGM's Little Bantamweight (1938), and Walter Lantz's The Bongo Punch (1958).

Live-action films that include scenes of the sport include the 1964 Mexican film El Gallo De Oro, the 1965 film The Cincinnati Kid, and the 1974 film Cockfighter, directed by Monte Hellman (based on the 1962 novel of the same name by Charles Willeford).

The 1990 film No Fear, No Die centers around two men who are part of an illegal cockfighting ring.

Cockfighting is depicted twice in the 2011 film The Rum Diary.

The Spike TV show 1000 Ways to Die features a death involving a cockfight, where a man who bets on a rooster attaches razors to its claws to ensure its winning, but is slashed to death himself.

In the Seinfeld episode "The Little Jerry", Kramer enters his rooster into a cockfight in order to get one of Jerry's bounced checks removed from a local bodega where the cockfights actually take place.

In the HBO series Eastbound & Down, Kenny Powers moves to Mexico and is in the cockfighting business until his cock "Big Red" dies.

The 2011 Tamil film Aadukalam revolves around the practice of cockfighting in Madurai, Tamil Nadu. In the FX Network's police drama, The Shield episode titled "Two Days of Blood" (season #1, episode #12), Detective Shane Vendrell and Detective Curt Lemansky go undercover in a cockfighting event to track down an illegal arms smuggler.

In literature

Abraham Valdelomar's 1918 tale El Caballero Carmelo depicts a cockfight between the protagonist, a cock named Carmelo, and his rival Ajiseco from a child's perspective, who considered this bird as an heroic member of his family. Nathanael West's 1939 novel The Day of the Locust includes a detailed and graphic cockfighting scene, as does the Alex Haley novel Roots: The Saga of an American Family and the miniseries based on it. In Gabriel Garcia Marquez's Nobel-Prize winning 1967 novel One Hundred Years Of Solitude, cockfighting is outlawed in the town of Macondo after the patriarch of the Buendia family murders his cockfighting rival and is haunted by the man's ghost. Cockfighting is central to García Marquez's 1965 novella No One Writes to the Colonel in which the unnamed protagonist sells all of his belongings to feed his murdered son's gamecock. Charles Willeford wrote a novel called Cockfighter in 1962, which gives a detailed account of the protagonist's life as a 'cocker'. A description of a border town cockfight fiesta can be found in On the Border: Portraits of America's Southwestern Frontier.[102]

In martial arts

The term "human cockfighting" was used by United States senator John McCain to describe mixed martial arts, which at the time he was campaigning to ban.[103]

In video games

The video game Law & Order: Legacies uses a cockfight as a plot point. A man died because a rooster with a spur slashed him, but with a twist that he would have survived if his wife had called the police.

Square Enix's video game Sleeping Dogs allows the player character to spectate and bet on various virtual cockfights based around the game's rendition of the city of Hong Kong.

The Pokémon Blazikien is based on a cockfighter chicken.

Gallery

Cockfight on the outskirts of Kabul, Afghanistan

Cockfight on the outskirts of Kabul, Afghanistan

Cockfight in Lima, Peru

Cockfight in Lima, Peru A Philippine gamecock

A Philippine gamecock- A Philippine "lasak", or off-color fighting cock in teepee, gamecocks cord

- Cockfight in Hilongos, Philippines

Painting of a traditional cockfighting village scene in southern Thailand

Painting of a traditional cockfighting village scene in southern Thailand Cockfight in Vietnam

Cockfight in Vietnam

See also

- Dog fighting

- Dubbing (poultry)

- Illegal sports

- Insect fighting

- Ram fighting

- Shamo (chicken)

References

- "gamecock". Merriam-Webster. 2012-08-31. Retrieved 2014-05-10.

First Known Use: 1634

- Raymond Hernandez (1995-04-11). "A Blood Sport Gets in the Blood; Fans of Cockfighting Don't Understand Its Outlaw Status". The New York Times. New York City Metropolitan Area. Retrieved 2014-05-10.

- Jim Bell (February 24, 2011). "East Texas Lawmaker Wants to Outlaw Cockfighting". KSFA 860 AM NewsTalk. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- Keys, Janette (2011). "Cock Fights / Peleas de Gallos". Guide to Colonial Zone Dominican Republic. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- Sherman, David M. (2002). Tending Animals in the Global Village. Blackwell Publishing. 46. ISBN 0-683-18051-7.

- Cockfighting. Encyclopædia Britannica 2008

- Iravatham Mahadevan. "'Address' Signs of the Indus Script" (PDF). Presented at the World Classical Tamil Conference 2010. 23–27 June 2010. The Hindu.

- Poultry Breeding and Genetics By R. D. Crawford – Elsevier Health Sciences, 1990, page 10

- Al-Nasser, A.; Al-Khalaifa, H.; Al-Saffar, A.; Khalil, F.; Albahouh, M.; Ragheb, G.; Al-Haddad, A.; Mashaly, M. (2007). "Overview of chicken taxonomy and domestication". World's Poultry Science Journal. 63 (2): 285. doi:10.1017/S004393390700147X.

- R. D. Crawford (1990). Poultry Breeding and Genetics. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 11. ISBN 9780444885579. Retrieved 2014-05-10.

- Curtis, Thomas (19 January 2018). "The London Encyclopaedia: Or, Universal Dictionary of Science, Art, Literature, and Practical Mechanics, Comprising a Popular View of the Present State of Knowledge. Illustrated by Numerous Engravings, a General Atlas, and Appropriate Diagrams". T. Tegg. Retrieved 19 January 2018 – via Google Books.

- "Tell en-Nasbeh: Biblical Mizpah of Benjamin". The College of Arts and Sciences, Cornell University.

- Miller, James M.; Hayes, John H. (1986). A History of Ancient Israel and Judah. Louisville, Kentucky: John Knox Press. p. 422. ISBN 978-0-664-21262-9.

- Taran, Mikhael (January 1975). "Early Records of the Domestic Fowl in Ancient Judea". Ibis. 117 (1): 109–110. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1975.tb04192.x.

- Borowski, Oded (2003). Daily Life in Biblical Times. Atlanta, Georgia: Society of Biblical Literature. pp. 69–70. ISBN 978-1-58983-042-4.

- "Ministry International Journal for Pastors – What is new in Biblical Archeology? by Siegfried H. Horn". Ministrymagazine.org. Retrieved 2014-05-10.

- Moseley, Henry Nottidge (1879). Notes by a Naturalist on the "Challenger". London: Macmillan and Co. p. 413.

- Staff (2011-02-06). "Cockfighting bird stabs, kills man". The New York Post. Nypost.com. Retrieved 2014-02-11.

- "Help expose illegal cockfighters". Irish Council Against Bloodsports. Retrieved February 22, 2008.

- "Death Match". The Scientist. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- "Animal Protection Group Calls on World Health Organization to Combat Cockfighting as Key Factor in Spread of Avian Flu". Humane Society of the United States. February 18, 2005. Archived from the original on February 19, 2008. Retrieved February 22, 2008.

- "Using Spirit Worship to Infuse Southeast Asia into the K-16 Classroom". Tun Institute of Learning. January 15, 2005. Archived from the original on December 3, 2012.

- "Seval Sandai in Tamil - Tamil Desiyam". Tamil Desiyam. 2018-08-14. Retrieved 2018-08-30.

- "Police move against cockfight faces opposition". The Hindu. Chennai, India. January 10, 2008. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- Justin, Denise A (January 9, 2012). "Cockfighting and Gambling Dominate India's 'Sun God' Festival". Opposing Views.

- "Bali-Cockfighting Tradition Lives". The Jakarta Post. Jakarta, Indonesia: Thejakartapost.com. 2002-01-24. Archived from the original on 2014-02-25. Retrieved 2014-02-11.

- Bali Today: Love and social life, By Jean Couteau, Jean Couteau et al., p128-129, Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia, 2005

- Bali, Sekala and Niskala: Essays on society, tradition, and craft, Fred B. Eiseman – page 240 – Periplus Editions, 1990

- Bali, Sekala and Niskala, Vol. 2: Essays on Society, Tradition, and Craft, Fred B. Eiseman Jr.

- "Emergency: 'Sentensyador'". Gmanews.tv. 2008-07-12. Archived from the original on 2010-04-03. Retrieved 2014-02-11.

- Dundes, Alan (1994). The Cockfight: A Casebook. Univ of Wisconsin Press. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-299-14054-0.

- Peters, Sharon (March 9, 2010). "Authorities crack down on finch-fighting rings". USA Today. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- "Police bust canary fighting operation". WTNH. July 27, 2009. Archived from the original on August 24, 2011. Retrieved November 25, 2011.

- "Ley 14346 - Malos Tratos y Actos de Crueldad a los Animales" (PDF) (in Spanish). National University of the Littoral. 27 November 1954. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- "Is cock fighting illegal in Australia?". RSPCA Australia knowledgebase. RSPCA Australia-Kb.rspca.org.au. 2009-03-17. Archived from the original on 2014-02-17. Retrieved 2014-02-11.

- "Dozens charged in major cockfight". 2012-09-09. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- Roel Damiaans (13 January 2020). "Hanengevechten zijn al 153 jaar verboden, maar vallen niet uit te roeien". Het Belang van Limburg (in Dutch). Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- "Overview of Brazil's Legal Structure for Animal Issues – Lane Azevedo Clayton – Animal Legal & Historical Center = Publish Date: 2011". Animallaw.info. Archived from the original on 2013-07-31. Retrieved 2014-05-10.

- "Brazilian animal law – Alex P". JoinUniverse. 2012-06-19. Archived from the original on 2013-03-13. Retrieved 2014-05-10.

- "Ley Núm. 20.380 Sobre Protección de Animales". LeyChile.cl (in Spanish). 3 October 2009. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- FM, La (2019-03-27). "Corte dice que corridas de toros y peleas de gallos son de arraigo cultural". www.lafm.com.co (in Spanish). Retrieved 2019-04-10.

- Semana. "Colombia acoge campeonato de peleas de gallos". Colombia acoge campeonato de peleas de gallos (in Spanish). Retrieved 2019-04-10.

- La Nacion Prohibición de galleras 2012. In Spanish

- Al Dia Archived 2011-08-12 at the Wayback Machine in Spanish

- Díaz-González, José Andrés; Bastos, Laura Solis. "Informe de Encuesta: Percepción sobre aspectos de la coyuntura y las culturas políticas en Costa Rica, 2016". Retrieved 19 January 2018. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Sequeira, Aarón (2017). "Maltratar a un animal será castigado hasta con 2 años de cárcel; multas serán hasta de ¢212.000". La Nación. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- Nick Kirkpatrick, Cockfighting has deep roots in Cuba, Washington Post (December 31, 2015).

- Sarah Marsh & Alexandre Meneghini, Cockfighting in Cuba: clandestine venues, state arenas, Reuters (April 20, 2017).

- Agustín Pupo Domenech, El Gallo Fino Cubano, 151 pp. Editorial SI-MAR, S.A., La Habana, Cuba 1995 (ISBN 9597054051).

- Revista Carteles, September 2, 1956.

- Reglamento para las lidias de gallos, Ayuntamiento de Holguín, Cuba 1909

- "Dominicans beware of US total ban on cockfights". Dominican Today. 14 December 2018. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- Foggo, D.; Campbell, M. (January 22, 2006). "British fans flock to French cockfights". The Times. London. Retrieved February 22, 2008.

- "Le Guide bu Nord de Pas de Calais" (in French). Region Nord Pas de calais. Archived from the original on February 5, 2008. Retrieved February 22, 2008.

- French court upholds ban on new cockfighting arenas, France24 (July 31, 2015).

- Nevins, Debbie (2015). Haiti: Third Edition. New York: Cavendish Square Publishing. p. 110. ISBN 9781502608031. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- "Decreto Nº 115-2015 ─ Ley de Protección y Bienestar Animal" (PDF) (in Spanish). Ecolex. 2016. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- "SC puts interim ban on 'cock-fights' sport in AP". Times of India. January 13, 2015.

- "This Sankranti, Rs 1,000 cr riding on roosters". Times of India. January 11, 2015.

- Srinivasa Rao Apparasu (January 17, 2018). "Banned, but cockfighting spikes in coastal Andhra Pradesh during Sankranti". Hindustan Times.

- Cook, William (January 3, 2015). "The Spectator". magazine. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- "Cockfighting in Iraq: a different kind of battle". Yourmiddleeast.com. 2012-04-11. Retrieved 2014-02-11.

- Louis Frédéric, Japan Encyclopedia (trans. Käthe Roth: Harvard University Press, 2002), pp. 132-33.

- Frank Stewart & Katsunori Yamazato, Voices from Okinawa: Featuring Three Plays by Jon Shirota (University of Hawaii Press, 2009), p. 56.

- Aleksin H. Ortega, "Cockfighting" in Encyclopedia of Latino Culture: From Calaveras to Quinceaneras, Vol. 1 (ed. Charles M. Tatum: Greenwood, 2014), pp. 757-58.

- The Tradition of Cockfighting in Mexico, Digg.

- Prohiben las peleas de gallos y perros en el df pero no las corridas de toros

- Prohíbe Coahuila peleas de gallos y de otros animales (Coahuila prohibits fighting of roosters and other animals)

- "Hanengevechten in Nederland: 'Dit zijn barbaarse praktijken'". RTL Nieuws (in Dutch). 11 December 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- "Animal Welfare Act 1999". www.legislation.govt.nz. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- "Cockfight signifies cruel culture – Thursday, 26 July 2012". Pakistantoday.com.pk. 2012-01-09. Retrieved 2014-05-10.

- "Panamá prohíbe las corridas de toros" (in Spanish). Anima Naturalis. 15 March 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- "Ley Nº 4840 / de Proteccion y Bienestar Animal". Leyes Paraguayas (in Spanish). Biblioteca y Archivo del Congreso de la Nación. 30 January 2013. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- "Cock and bull fighting are legal, Peru's top court rules". Deutsche Welle. 26 February 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- "Banned on Rizal Day: cockfighting, horse-racing and jai-alai". Rappler. 28 December 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- Noreen Jazul (March 16, 2020). "DILG bans cockfighting until April 14". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- "DILG bans local officials traveling overseas amid COVID-19 crisis". ABS-CBN News. March 14, 2020. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- "Davao City bans cockfights, small-town lottery". Rappler. April 17, 2020. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- "Peleas de gallo, una actividad legal en Andalucía". canalsur.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 2019-03-18.

- Octavio Toledo, Cockfighting ban for Canary Islands fizzles out in Congress, El País (February 16, 2015).

- Collins, T. (2005). Encyclopedia of Traditional British Rural Sports. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35224-6. Retrieved December 5, 2007.

- "Cockpit". National Museum Wales. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- McClure, David (1994). Tolls and Tacksmen. Ayr Arch & Nat Hist Soc. Ayrshire Monograph No. 13. p. 53.

- Hilpern, Kate (October 20, 2007). "What lies behind the rise in animal fighting?". Independent. London. Retrieved March 14, 2008.

- "Louisiana State House passes Cockfighting ban". Wafb.com. 2014-02-04. Archived from the original on 2009-05-25. Retrieved 2014-02-11.

- Legisladores de Luisiana aprueban prohibición a pelea de gallos June 27, 2007 La Voz (in Spanish)

- Fact Sheet: Cockfighting: State Laws, Humane Society of the United States (updated April 2013).

- HSLF (February 4, 2014). "Farm Bill Strengthens Animal Fighting Law, Maintains State Farm Animal Protection Laws". Humane Society of the United States.

- Jon Perez, "Cockfighting Ban Now Law", Saipan Tribune, 24 December 2018.

- "Cock-fighting in Puerto Rico". Townsville Daily Bulletin (Qld. : 1907–1954). 4 May 1953. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- Meredith Hoffman, Cockfighting is Puerto Rico's Most Resilient Industry, Vice (February 16, 2016).

- Sanchez, Ray (December 19, 2019). "Puerto Rico defies US cockfighting ban; court ban likely". CNN. Retrieved December 19, 2019.

- "H.R. 137: Animal Fighting Prohibition Enforcement Act of 2007". GovTrack.us. Retrieved February 22, 2008.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-04-26. Retrieved 2012-10-04.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) The Animal Welfare Act: Background and Selected Legislation by Tadlock Cowan – Analyst in Natural Resources and Rural Development – September 9, 2010

- Antenucci, Antonio (10 February 2014). "70 arrested in NY's largest cockfighting bust". New York Post. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- Assefa, Haimy (10 February 2014). "New York cockfighting bust uncovers 3,000 birds and yields 9 arrests". CNN. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- "NY AG: 3,000 Birds Rescued in Cockfighting Bust". ABC News. 10 February 2014. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- Hamilton, Matt (May 16, 2017). "7,000 birds seized in largest cockfighting bust in U.S. history, L.A. County authorities say". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 17, 2017.

- "Cockfighting Bust in LA County Town Nets 7,000 Birds". NBC Los Angeles. May 16, 2017. Retrieved May 17, 2017.

- Moyer, Justin (17 July 2014). "A Romanian princess pleads guilty to cockfighting. Say what?". Washington Post. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- Carson, Teresa (16 July 2014). "Romanian princess admits running cockfighting ring in Oregon". Reuters. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- Miller, Tom. On the Border: Portraits of America's Southwestern Frontier, pp. 39–45.

- "John McCain talks UFC and MMA". Mmaroot.com. Archived from the original on 2011-07-14. Retrieved 2014-05-10.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cockfighting. |