Francization

Francization (in American English and Canadian English) or Francisation (in British English), Frenchification, or Gallicization designates the expansion of French language use through adoption by more and more social groups who had not before—whether as a first language or not, and whether the adoption was forced upon or sought out by the concerned population.[1][2][3][4] According to the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie (OIF), the figure of 220 million Francophones is sous-évalué (under-evaluated)[5] because it only counts people that can write, understand and speak French fluently, thus excluding a large part of the African French-speaking population that does not know how to write.[6] The French Conseil économique, social et environnemental estimate that, if the population that does not know how to write were included as francophones, the total number of French speakers passed 500 million in the year 2000.[7] French has the world's fastest-growing relative share of speakers.

In 2014, a study from the French Bank, Natixis Bank, claims French will become the world's most-spoken language by 2050.[8][9][10] However, critics of the study state that French coexists with other languages in many countries and the study’s estimations are prone to great overstatement.

The number of Francophones or French-language speakers in the world has been rising substantially since the 1980s. In 1985, there were 106 million Francophones around the world. That number quickly rose to 173.2 million in 1997, 200 million in 2005, 220 million in 2010 (+10 % from 2007)[11] and reached 274 million in 2014.[12] Forecasts expect that the number of French speakers in Africa alone will reach 400 million in 2025, 715 million (readjusted in 2010)[13] by 2050 and reach 1 billion and 222 million in 2060 (readjusted in 2013).[14] The worldwide French-speaking population is expected to multiply by a factor of 4, whereas the world population is predicted to multiply by a factor of only 1.5.[15]

Africa

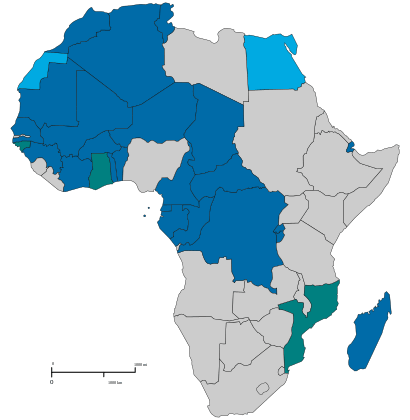

Africa has 32 French-speaking countries, more than half its total (53);[16] French was also the most widely spoken language in Africa in 2015.[17]

However, Nigeria, the most populous country on the continent, predominantly speaks English.[18]

The Francophone zone of Africa is two times the size of the United States of America (including Alaska).[19]

French was introduced in Africa by France and Belgium during the colonial period. The process of francization continued after the colonial period, so that English-speaking countries like Ghana or Nigeria feel strong French influences from their French-speaking neighbours.

French became the most spoken language in Africa after Arabic and Swahili in 2010.[20] The number of speakers changed very rapidly between 1992 and 2002, with the number of French learners in sub-Saharan Africa increasing by 60.37 %, from 22,33 million to 34,56 million people.[21] A similar trend in the Maghreb region is occurring. However, as figures provided by the OIF for the Maghreb region were combined with those of the Middle East, the exact count for the Maghreb countries alone is not possible. In this larger region (Maghreb and Middle East), an increase from 10.47 million to 18 million people learning French was observed between 1992 and 2002.

Consideration should be given to the number of French speakers in each country to get an idea of the importance the French language holds in Africa.

Many African countries without French as an official language have recently joined the OIF in view of francizing their countries:

- Cape Verde (official language: Portuguese)

- Egypt (official language: Arabic)

- Ghana (official language: English)

- Guinea Bissau (official language: Portuguese)

- Mozambique (official language: Portuguese)

- São Tomé and Príncipe (official language: Portuguese)

The French language currently plays an important role in Africa, serving more and more as a common language or mother tongue (in Gabon, Ivory Coast, Congo, Cameroon and Benin in particular). The African Academy of Languages was established in 2001 to manage the linguistic heritage.[22]

Francophone African countries counted 370 million inhabitants in 2014. This number is expected to reach between 700 and 750 million by 2050.[23] There are already more francophones in Africa than in Europe.[24]

Asia

Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos were once part of French Indochina, part of the French Empire. French culture, in aspects of architecture, culinary and linguistics, have been integrated into the local ones, although the latter remained highly distinct. French language used to be the official language and was considerably popular and influential in these colonies, but after they were decolonised and gained independence, the new governments generally removed its influence, by implementing the native language as the only official language in the newly independent states. Currently, the presence of French language in these countries are negligibly minor.

Europe

Great Britain

Great Britain, and therefore the English language, was deeply francized during the Middle Ages. This was a result of the conquest of England by William the Conqueror from Normandy in 1066, a king who spoke exclusively French and imposed the French language in England. Old English became the language of the poor population and French the language of the court and wealthy population. It is said that during this period, people in England spoke more French than those in France.[25] Today, it is estimated that 50 % to 60 % of the English language comes from French or Latin.[26]

It is easy to observe this tendency in the cooking world. The names of living farm animals have Anglo-Saxon roots. However, the names of cooked animals, once served to the wealthier, have Old French origins:[27]

- Pig (Anglo-Saxon) – Pork from the Old French porc

- Cow (Anglo-Saxon cou) – Beef from the Old French bœuf

- Chicken (Anglo-Saxon) – Poultry from the Old French pouletrie or poule

There is an incomplete list of French expressions used in English, containing however only pure French expressions (not evolved/modified words with French roots): List of French expressions in English.

France

Within France

Francization is also a designation applied to a number of ethnic assimilation policies implemented by French authorities from the French Revolution to present. These policies aimed to impose or to maintain the dominance of French language (which at this time was still a minority language in the numerical sense, despite being the prestige language of France and an increasingly important vernacular for writing, with the decline of Latin) and culture by encouraging or compelling people of other ethnic groups to adopt French, thereby developing a French identity at the expense of their existing one. Coupled with this policy was the deliberate suppression of minority languages. Quickly after the end of the Ancien Régime, the new revolutionary government adopted a policy of promotion of French as a unifying and modernizing language, simultaneously denigrating the status of minority languages as bulwarks of feudalism, Church control of the state, and backwardness in general. In less than a year after coming to power (1792), the Committee for Public Instruction mandated that the newly expanded public education would be buttressed by the sending of French-speaking teachers to areas that spoke other languages.[28] The 19th century saw this programme achieve many of its intended aims: the French language became much more expansive among the population and, by the 1860s, nearly 80 % of the national population were able to speak French.[29]

Only at the turn of the twentieth century did French become the mother language of the adult population's majority in the French Third Republic, thanks to Jules Ferry's free, compulsory education, which pursued more or less explicitly the strengthening of the central state by means of instilling a French national identity in the population.[30] French was presented as the language of modernity, as opposed to regional languages such as Breton or Basque, labelled as barbaric or tribal, the use of which was punished at school by having pupils caught speaking them display tokens of shame.[31] In Occitan-speaking areas that school policy was called the vergonha.

Up to 1992, no official language was recognized in the French constitution. That year, the hegemony of French was further reinforced by declaring it constitutionally the language of the French republic. In 1998, France became a signatory of the European Charter on Minority Languages; however, it has yet to ratify it, with general agreement among the political class that supportive measures are neither popular enough to attract great support nor banal enough to avert controversy, with concerns specifically about courts forcing the state to act if the rights enshrined in the charter are recognised.

National minorities

The term can be applied to the francization of the Alemannic-speaking inhabitants of Alsace and the Lorraine Franconian-speaking inhabitants of Lorraine after these regions were conquered by Louis XIV during the seventeenth century, to the Flemings in French Flanders, to the Occitans in Occitania, as well as to Basques, Bretons, Catalans, Corsicans and Niçards.

It began with the ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts under King Francis I of France, that prescribed the official use of the French language, the langue d'oïl dialect spoken at the time in the Île-de-France, in all documents. Other tongues, such as Occitan, began to disappear as written languages.

Everything was francized step by step, starting with surnames and place names. Presently, it still continues, but some change their names to rebretonize (replacement of 'Le' by 'Ar' for instance Le Bras becomes Ar Braz 'the tall') or reoccitanize them. City signs for example, might be spelled in French, but the local authorities are now allowed to add the historic version. However, the process is limited by the refusal of the French Government to recognize minority languages in France, on the basis of the French Constitution, which states that "The language of the Republic of France is French."

French Colonial Empire

Belgium

Brussels and the Flemish periphery

In the last two centuries, Brussels transformed from an exclusively Dutch-speaking city to a bilingual city with French as the majority language and lingua franca. The language shift began in the eighteenth century and accelerated as Belgium became independent and Brussels expanded beyond its original city boundaries.[32][33] From 1880 onwards, more and more Dutch-speaking people became bilingual, resulting in a rise of monolingual French speakers after 1910. Halfway through the twentieth century, the number of monolingual French-speakers carried the day over the (mostly) bilingual Flemish inhabitants.[34] Only since the 1960s, after the fixation of the Belgian language border and the socio-economic development of Flanders was in full effect, could Dutch stem the tide of increasing French use.[35] The francization of the Flemish periphery around Brussels still continues because of the continued immigration of French speakers coming from Wallonia and Brussels.

North America

Canada

Quebec

The Government of Quebec has francization policies intended to establish French as the primary language of business and commerce. All businesses are required to provide written communications and schedules in French, and may not make knowledge of a language other than French a condition of hiring unless this is justified by the nature of the duties. Businesses with more than fifty employees are required to register with the Quebec Office of the French language in order to become eligible for a francization certificate, which is granted if the linguistic requirements are met. If not, employers are required to adopt a francization programme, which includes having employees, especially ones in managerial positions, who do not speak French or whose grasp of French is weak attend French-language training.[36]

As part of the francization programme, the Quebec government provides free language courses for recent immigrants (from other countries or other provinces) who do not speak French or whose command of French is weak. The government also provides financial assistance for those who are unable to find employment because they are unable to speak French.[37]

Another aspect of francization in Quebec regards the quality of the French used in Quebec. The Quebec Office of the French language has, since its formation, undertaken to discourage anglicisms and to promote high standards of French-language education in schools.[38]

The francization programmes have been considered a great success. Since 1977 (the year the Charter of the French Language became law), the number of English speakers has decreased from 14 % in 1970 to less than 6.7 % in 2006. In the 1970s the French language was generally understood only by native French speakers, who were 80 % of the population of Quebec. In 2001, French was understood by more than 94 % of the population.[39] Moreover, the number of immigrants sending their children to English schools fell from 80 % in 1970 to less than 4 % in 2006.

French is also becoming increasingly attractive to foreign speakers, suggesting that the francization programmes have been successful.

Montreal is a particular interesting case because, unlike the rest of Quebec, the French-speaking proportion of the population diminished. However, this does not mean that the francization programmes failed, as the share of English speakers diminished as well; it seems more likely that the decrease was caused by the fact that 93 % of new immigrants to Quebec choose to settle in Montreal,[40] with a corresponding rise in languages other than English and French. The government of Quebec estimates that, over the next 20 years, the Francophone proportion of Montreal will go back up.[41]

But those estimations seem to underestimate the francization of Montreal for some experts, because statistics show that the proportion has already risen from 55.6 % (1996) to 56.4 % (2001).[42]

The success of francization of Quebec can also be seen over the borders of its territory: in Ontario, the proportion of English speakers dropped from 70.5 % in 2001 to 68 % in 2006,[43][44] while the proportion of French speakers went up from 4.06 % (488 815) in 2006 to 4.80 % (580 000) in 2009. However, this statistic must be examined in conjunction with the effects of Quebec francophone out-migration. Interprovincial migration, especially to Ontario, results in a net loss of population in Quebec. The number of French-speaking Quebecers leaving the province tends to be similar to the number entering, while immigrants to Quebec tend to leave.[45]

None of the Quebec statistics are adjusted to compensate for the percentage—approximately 20 %—of Anglophones who departed the province by the mid-1980s as a consequence of linguistic nationalism.[46] By 2001, over 60 % of the 1971 population of Quebec Anglophones had left the province.[47]

The Charter of the French Language has been a complete success, according to Hervé Lavenir de Buffon (general secretary of the « Comité international pour le français, langue européenne »), who said in 2006: "Before Bill 101, Montreal looked like an American city. Now Montreal looks like a French-speaking city; that proves how well Bill 101 has worked!"[48]

New Brunswick

The policy has been even more successful in New Brunswick, for example: the city of Edmundston went from 89 % French-speaking in 1996 to 93.4 % in 2006, the city of Moncton from 30.4 % in 1996 to 33 % in 2006, Dalhousie (from 42.5 % to 49.5 %) and Dieppe (from 71.1 % in 1996 to 74.2 % in 2006). Some cities even passed 50% of French speakers between 1991 and 2006 like Bathurst, which passed from 44.6 % of French speakers in 1996 to 50.5 % in 2006, or Campbellton, from 47 % in 1996 to 55 % in 2006.[49][50][51]

Rates of francization may be established for any group by comparing the number of people who usually speak French to the total number of people in the minority language group. See Calvin Veltman's Language Shift in the United States (1983) for a discussion.

Of the language

There are many examples of francization in history and popular culture:

- Crème anglaise replacing the word "custard" on restaurant menus.

- Anne Boleyn choosing the French spelling Boleyn over the traditional English Bolin or Bullen.

- Mary, Queen of Scots, choosing the spelling Stuart over Stewart for the name of her dynasty. (The Scots had dual nationality and Mary, Queen of Scots was brought up in France.)

- The common "-escu" final particle in Romanian being traditionally changed to "-esco" in French spellings and being occasionally adopted by the persons themselves as a French equivalent of their names (see Eugène Ionesco, Irina Ionesco, Marthe Bibesco).

- Courriel, short for courrier électronique, replacing e-mail (originally from Quebec).

The same exists for other languages, for example, English, in which case objects or persons can be anglicized.

See also

| Look up francisation in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Afrancesado, Spanish followers of French culture and politics in the 18th and 19th centuries

- Anglicism

- French colonial empires

- Gallicism

References

- "FRANCISÉ : Définition de FRANCISÉ". Ortolang (in French). Centre National de Ressources Textuelles et Lexicales. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- Dictionnaire Général Et Grammatical, Des Dictionnaires Français, Tome 2°, 1851.

- Nouveau Vocabulaire Français, Où L'on A Suivi L'orthographe Adoptée.

- Le Québécois - Dictionnaires et Langues.

- "TV5MONDE : TV internationale francophone : Info, Jeux, Programmes TV, Météo, Dictionnaire". Tv5.org. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- "L'Afrique, un continent refuge pour la francophonie". Afrique Avenir. 15 October 2010. Archived from the original on 9 April 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- "Discours". La voix de la diversité. Organisation internationale de la Francophonie. Archived from the original on 16 May 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- "FRANCE - Le français, langue la plus parlée en 2050 ?". France24.com. 26 March 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- Pierre Haski (25 March 2014). "Le français sera la langue la plus parlée dans le monde en 2050 - Rue89 - L'Obs" (in French). Rue89.nouvelobs.com. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- "Le français sera-t-il la langue la plus parlée en 2050 ?". Lesinrocks.com. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- "La Francophonie ne progresse pas qu'en Afrique - Général - RFI". Rfi.fr. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- "274 millions de francophones dans le monde - Organisation internationale de la Francophonie". www.francophonie.org. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- (in French) Cahiers québécois de démographie, vol. 31, n° 2, 2003, p. 273-294.

- "Un milliard de francophones en 2060". Lefigaro.fr. 20 March 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- (in French) Cahiers québécois de démographie, vol. 32, n° 2, 2003, p. 273-294

- Chigozie, Emeka (21 August 2015). "List of French Speaking African Countries". Answers Africa. Archived from the original on 26 September 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- "La résistance de la langue française face à l'hégémonie anglo-saxonne". Le Bréviaire des Patriotes (in French). 27 February 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- "Coming of age: English in Nigeria".

- List of countries and dependencies by area

- "Langues du monde". www.babla.fr. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- "Organisation internationale de la Francophonie". www.francophonie.org. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- "Background". African Academy of Languages. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- Gobry, Pascal-Emmanuel (21 March 2014). "Want To Know The Language Of The Future? The Data Suggests It Could Be...French". Forbes. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- Wood, Ed M. "How Many People Speak French, And Where Is It Spoken?". The Babbel Magazine. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- Jacques Leclerc. "Histoire du français: Ancien français". Axl.cefan.ulaval.ca. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- "Histoire du français". Axl.cefan.ulaval.ca. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- Jacques Leclerc (14 October 2014). "Histoire du français: le moyen français". Axl.cefan.ulaval.ca. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- "Histoire du français: La Révolution française et la langue nationale". www.axl.cefan.ulaval.ca. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- "Histoire du français: Le français contemporain". www.axl.cefan.ulaval.ca. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- Watson, Cameron (2003). Modern Basque History: Eighteenth Century to the Present. University of Nevada, Center for Basque Studies. p. 210. ISBN 1-877802-16-6.

- Watson (1990), p. 211.

- Archived 5 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "Université Laval: Accueil". Ulaval.ca. Archived from the original on 19 June 2009. Retrieved 2015-05-29.

- (in Dutch) "Thuis in gescheiden werelden" — De migratoire en sociale aspecten van verfransing te Brussel in het midden van de 19e eeuw" Archived 15 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine, BTNG-RBHC, XXI, 1990, 3-4, pp. 383-412, Machteld de Metsenaere, Eerst aanwezend assistent en docent Vrije Universiteit Brussel

- J. Fleerackers, Chief of staff of the Belgian Minister for Dutch culture and Flemish affairs (1973). "De historische kracht van de Vlaamse beweging in België: de doelstellingen van gister, de verwezenlijkingen vandaag en de culturele aspiraties voor morgen". Digitale bibliotheek voor Nederlandse Letteren (in Dutch).

- Archived 8 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Information from the Quebec government

- "English section- The Charter of the French language". Oqlf.gouv.qc.ca. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- Archived 6 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "Annexe | Le français langue commune :enjeu de la société québécoise :bilan de la situation de la langue française au Québec en 1995 :rapport | Conseil supérieur de la langue française". Cslf.gouv.qc.ca. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- "OQLF_FasLin-01-e.indd" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 December 2006. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- "OQLF_FasLin-01-d.indd" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 December 2006. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- "Profils des communautés de 2001" (in French). 2.statcan.gc.ca. 12 March 2002. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- "Profils des communautés de 2006 – Province/Territoire" (in French). 2.statcan.gc.ca. 5 February 2010. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- Statistics Canada. "Factors Affecting the Evolution of Language Groups". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 2006-10-27

- David Pettinicchio. "Migration and ethnic nationalism: Anglophone exit and the 'decolonisation' of Québec" (PDF). Jsis.washington.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2015. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- "Find more at North.ca | All Canadian : All The Time". Qln.ca. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- "L'avenir du français en Europe". Canalacademie.com. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- "Profils des communautés de 2006 - Région métropolitaine de recensement/Agglomération de recensement" (in French). 2.statcan.gc.ca. 5 February 2010. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- "Profils des communautés de 2001" (in French). 2.statcan.gc.ca. 12 March 2002. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- "Profils des communautés de 2006 - Subdivision de recensement" (in French). 2.statcan.gc.ca. 5 February 2010. Retrieved 10 September 2010.