French cruiser Jurien de la Gravière

Jurien de la Gravière was a protected cruiser built for the French Navy in the late 1890s and early 1900s, the last vessel of that type built in France. Intended to serve overseas in the French colonial empire, the ship was ordered during a period of internal conflict between proponents of different types of cruisers. She was given a high top speed to enable her to operate as a commerce raider, but the required hull shape made her maneuver poorly. The ship also suffered from problems with her propulsion machinery that kept her from reaching her intended top speed. She carried a main battery of eight 164 mm (6.5 in) guns and was protected by a curved armor deck that was 35–65 mm (1.4–2.6 in) thick.

Jurien de la Gravière underway early in her career | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Operators: |

|

| Preceded by: | D'Estrées class |

| Succeeded by: | None |

| History | |

| Name: | Jurien de la Gravière |

| Builder: | Lorient |

| Laid down: | November 1897 |

| Launched: | 26 June 1899 |

| Completed: | 1903 |

| Stricken: | 1922 |

| Fate: | Broken up |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Protected cruiser |

| Displacement: | 5,595 long tons (5,685 t) |

| Length: | 137 m (449 ft 6 in) loa |

| Beam: | 15 m (49 ft 3 in) |

| Draft: | 6.3 m (20 ft 8 in) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 22.9 knots (42.4 km/h; 26.4 mph) |

| Range: | 9,300 nmi (17,200 km; 10,700 mi) at 10 kn (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: | 463 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

Completed in 1903, Jurien de la Gravière initially served in the Atlantic Naval Division. Over the following several years, she made a number of visits to the United States, including to commemorate the centennial of the Louisiana Purchase in 1903. During another visit in 1906, she collided with and sank a schooner. Jurien de la Gravière had been transferred to the Reserve Division of the Mediterranean Squadron by 1911, though she was reactivated in 1913 to serve with the main French fleet. She remained on active service into the start of World War I in August 1914, and after ensuring the safe passage of French Army units, the fleet entered the Adriatic Sea to engage the Austro-Hungarian Navy. This resulted in the Battle of Antivari, where Jurien de la Gravière was detached to pursue the fleeing torpedo boat SMS Ulan, though she failed to catch her.

Jurien de la Gravière saw no further action during the conflict. The French fleet withdrew to blockade the southern end of the Adriatic and the Austro-Hungarians refused to send their fleet to engage them. After Italy's entry into the war in 1915, the French turned over control of the blockade and withdrew the bulk of the fleet. In October 1916, Jurien de la Gravière was detached to bombard the southern Anatolian coast of the Ottoman Empire. Later that year the fleet was moved to Greek waters to try to coerce the neutral Greek government to join the Allies, which they eventually did. Coal shortages kept the French from conducting any significant operations in 1918. After the war, Jurien de la Gravière served with the Syrian Division until early 1920, when she was recalled to France. She was subsequently sold to ship breakers.

Design

In the mid-1880s, elements in the French naval command argued over future warship construction; the Jeune École advocated building long-range and fast protected cruisers for use as commerce raiders on foreign stations while a traditionalist faction preferred larger armored cruisers and small fleet scouts, both of which were to operate as part of the main fleet in home waters. By the end of the decade and into the early 1890s, the traditionalists were ascendant, leading to the construction of several armored cruisers of the Amiral Charner class, though the supporters of the Jeune École secured approval for one large cruiser built according to their ideas, which became D'Entrecasteaux. Two more large protected cruisers, Châteaurenault and Guichen, were authorized in 1894.[1]

Political conflicts over cruiser construction continued over the next three years, and the French Chamber of Deputies rejected a request to build a sister ship to D'Entrecasteaux in 1896. By that time, Admiral Armand Besnard had become the Naval Minister. He was a proponent of the concept of dedicated colonial cruisers, and he sought to include such a vessel in the 1897 budget. The Chamber of Deputies agreed with the proposal for a 5,700-long-ton (5,800 t) protected cruiser. But the Conseil des Travaux (Council of Works), which had become dominated by those who favored a cruiser fleet composed of armored cruisers, rejected Besnard's proposed cruiser. Besnard nevertheless ordered the cruiser, which became Jurien de la Gravière, over their objections in late 1896. The design for the ship was prepared by Louis-Émile Bertin.[2] She proved to be the last protected cruiser to be built for the French Navy, as the naval command decided to build larger armored cruisers for all cruiser tasks, including colonial patrol duties.[3][4]

General characteristics and machinery

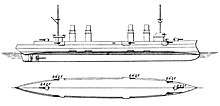

Jurien de la Gravière was 137 m (449 ft 6 in) long overall, with a beam of 15 m (49 ft 3 in) and a draft of 6.3 m (20 ft 8 in). She displaced 5,595 long tons (5,685 t). Steering was controlled by a single rudder. She handled poorly and her turning radius was 2,000 m (2,200 yd); this was a result of the ship's large length to beam ratio. Her length allowed the designers to incorporate very fine lines for greater hydrodynamic efficiency, but rendered her significantly less maneuverable compared to foreign contemporaries like the British cruiser HMS Hyacinth. Her crew numbered 463 officers and enlisted men.[3][5]

Her hull had a long forecastle deck that extended almost her entire length, stepping down to a quarterdeck toward her stern. The hull was sheathed in wood and a layer of copper plating to protect it from biofouling on lengthy cruises overseas, where shipyard facilities would be limited. The ship was fitted with a pair of light pole masts for observation and signalling purposes. Her superstructure was fairly minimal, consisting of a conning tower and bridge structure forward and a smaller, secondary conning position aft.[3]

The ship's propulsion system consisted of three vertical triple-expansion steam engines driving three screw propellers. Each engine was placed in an individual engine room. Steam was provided by twenty-four coal-burning, Guyot-du Temple-type water-tube boilers. These were ducted into four funnels that were placed in widely spaced pairs, one set directly aft of the fore mast and the other pair further aft. Her machinery was rated to produce 17,400 indicated horsepower (13,000 kW) for a top speed of 22.9 knots (42.4 km/h; 26.4 mph). Her propulsion system suffered from several problems, including cramped engine rooms and excessive vibration at high speed. Coal storage amounted to 886 long tons (900 t).[3] Her cruising range was 9,300 nautical miles (17,200 km; 10,700 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[6]

Armament and armor

.jpg)

Jurien de la Gravière was armed with a main battery of eight 164 mm (6.5 in) M1893 45-caliber (cal.) quick-firing (QF) gun in single pivot mounts. Two of the guns were in shielded pivot mounts on the upper deck, both on the centerline, one forward and one aft. The other six were in sponsons in the upper deck, three guns per broadside. The guns fired a variety of shells, including solid cast iron projectiles, and explosive armor-piercing and semi-armor-piercing shells. The muzzle velocity ranged from 770 to 880 m/s (2,500 to 2,900 ft/s).[3][7]

For defense against torpedo boats, she carried a secondary battery of ten 47 mm (1.9 in) 3-pounder Hotchkiss guns and six 37 mm (1.5 in) 1-pounder guns. All of these guns were carried in individual pivot mounts in various positions along the ship's upper deck and superstructure. She carried a pair of 450 mm (17.7 in) torpedo tubes; according to Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, these were submerged in the hull.[3] But the contemporary Journal of the American Society of Naval Engineers states that the tubes were mounted in the hull above the waterline.[5] The torpedoes were the M1892 variant, which carried a 75 kg (165 lb) warhead and had a range of 800 m (2,600 ft) at a speed of 27.5 knots (50.9 km/h; 31.6 mph).[8]

The ship had a curved armor deck that was 55 mm (2.2 in) thick on the flat portion, directly above the ship's propulsion machinery spaces and ammunition magazines. Toward the sides of the hull, it sloped downward to provide a measure of vertical protection, terminating at the side of the hull. The sloped portion increased slightly in thickness to 65 mm (2.6 in), though toward the bow and stern, it was reduced to 35 to 55 mm (1.4 to 2.2 in). Above the armor deck was a cofferdam that was 380 mm (15 in) wide and was composed of numerous watertight compartments. An anti-splinter deck that was 25 mm (0.98 in) thick formed the roof of the cofferdam, and the entire structure was intended to contain flooding in the event of damage. The forward conning tower was protected by 100 mm (3.9 in) on the sides. The ship's main guns were each fitted with gun shields that were 70 mm (2.8 in) thick, and their ammunition hoists were protected by armored tubes of 25 mm thick steel.[9]

Service history

Work began on Jurien de la Gravière with her keel laying in November 1897 at the Arsenal de Lorient in Lorient.[3] She was launched on 26 July 1899,[10] and after completing fitting-out, began her sea trials before formal acceptance by the French Navy. The trials were interrupted in July 1902 by an accident with her propulsion system.[11] The ship was commissioned in March 1903 for service on the North Atlantic station, but she had to return to port due to problems with her engines. She departed Lorient on 23 July, initially bound for the West Indies, but after a day at sea, she was forced to return to port. Her boiler rooms had become dangerously hot, ranging in temperature from 100 to 150 °F (38 to 66 °C), her boiler tubes leaked continuously, and she was unable to keep to her intended speed. In that condition, her cruising radius was less than half of what had been intended, around 4,000 nautical miles (7,400 km; 4,600 mi).[6][12] Work on the ship was completed later that year.[3] At this time, the ship was painted the standard color scheme of the French fleet; green below the waterline, a black upper hull, and buff superstructure.[13]

Upon entering service in 1903, Jurien de la Gravière was assigned to the Atlantic Naval Division, along with the armored cruiser Dupleix. When she joined the unit, she replaced the protected cruiser D'Estrées. The ship departed Lorient on 24 July, bound for the West Indies, where she joined the rest of the unit.[14] In December, Jurien de la Gravière was sent to the United States to represent France during the centennial celebration of the Louisiana transfer from France to the United States. She was present for the three-day festivities that began on 18 December. The Spanish cruiser Rio de la Plata and the US cruiser USS Minneapolis, the training ship USS Yankee, and the gunboat USS Topeka joined her for the celebration.[15] She remained in the unit in 1904 with Dupleix, being joined that year by the protected cruisers Troude and Lavoisier.[16] She remained in the unit the following year.[17] While visiting the United States on 10 July 1906, Jurien de la Gravière collided with the American 130-gross register ton schooner Eaglet in the North River between New York City and New Jersey. Eaglet was lost, but all four people aboard her survived.[18]

In 1908, the French Navy adopted a new paint scheme that retained the green bottom hull, but replaced the above-water colors with a uniform blue-gray.[13] By 1911, Jurien de la Gravière had been assigned to the Reserve Division of the Mediterranean Fleet, based in Toulon. The unit initially also included the armored cruisers Victor Hugo and Jules Michelet and the protected cruiser Châteaurenault, and later that year, it was strengthened with the addition of the armored cruiser Jules Ferry.[19] She remained in the unit the following year, and was activated to take part in the annual fleet maneuvers that began on 17 July 1912 and lasted for a week.[20]

In 1913, Jurien de la Gravière was mobilized to join the active component of the Mediterranean Fleet. She sailed on 20 October in company with the battleships of the 1st Squadron and six torpedo boats to make a show of force during a period of tension between Italy and the Ottoman Empire. The French ships visited Alexandria, Egypt, where they were visited by thousands of people. They then steamed north past Cyprus on 3 November, then back west to Messina, Italy, two days later. On the way there, they met the German battlecruiser SMS Goeben. The fleet then returned to the eastern Mediterranean, visiting a series of ports in Ottoman Syria. The ships then steamed to the Dardanelles straits, where the commander, Admiral Augustin Boué de Lapeyrère, transferred from his flagship, the pre-dreadnought Voltaire, to Jurien de la Gravière, to enter the straits and make an official visit to the Ottoman capital, Constantinople. The fleet then sailed to Salamis, Greece, to meet King Constantine I of Greece aboard his fleet's flagship, the armored cruiser Georgios Averof on 28 November. After a week visiting other Greek ports, the French vessels stopped in Porto-Vecchio in Corsica before rejoining the rest of the Mediterranean Fleet at Porquerolles. They arrived back in Toulon finally on 20 December.[21]

On 1 August 1914, Jurien de la Gravière departed from Toulon in company with the 2nd Submarine Flotilla, bound for Bizerte. By that time, Europe had already begun to spiral into World War I following the July Crisis that resulted in Austria-Hungary's declaration of war on Serbia over the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in late June. Boué de Lapeyrère ordered the fleet to mobilize the following day and steam to the North African coast to cover the transport of French units in French North Africa to mainland France. Boué de Lapeyrère received word of the start of hostilities with Germany in the early hours of 4 August.[22]

World War I

1914–1915

Faced with the prospect that the German Mediterranean Division—centered on Goeben—might attack the troopships carrying the French Army in North Africa to metropolitan France, the French fleet was tasked with providing heavy escort to the convoys. But instead of attacking the convoys, Goeben bombarded Bône and Philippeville and then fled east to the Ottoman Empire. Jurien de la Gravière was sent with the armored cruisers Bruix, Latouche-Tréville, and Amiral Charner to patrol the Strait of Sicily on 7 August to free British forces to pursue Goeben and the light cruiser SMS Breslau as they sailed eastward. After completing this mission, the Mediterranean Fleet then turned to confront the fleet of Germany's ally, the Austro-Hungarians, in the Adriatic Sea after France and the United Kingdom declared war on that country on 12 August.[23][24]

The French fleet was therefore sent to the southern Adriatic Sea to contain the Austro-Hungarian Navy. At that time, Jurien de la Gravière was attached to the Dreadnought Division, which at that time only included the new dreadnought battleships Jean Bart and Courbet.[25] On 15 August, the French fleet arrived off the Strait of Otranto, where it met the patrolling British cruisers HMS Defence and HMS Weymouth north of Othonoi. Boué de Lapeyrère then took the fleet into the Adriatic in an attempt to force a battle with the Austro-Hungarian fleet; the following morning, the British and French cruisers spotted vessels in the distance that, on closing with them, turned out to be the protected cruiser SMS Zenta and the torpedo boat SMS Ulan, which were trying to blockade the coast of Montenegro. In the ensuing Battle of Antivari, Boué de Lapeyrère initially ordered his battleships to fire warning shots, but this caused confusion among the fleet's gunners that allowed Ulan to escape. Jurien de la Gravière and several torpedo boats were detached to pursue Ulan, but they were unable to catch her. The slower Zenta attempted to evade the French battleships, but she quickly received several hits that disabled her engines and set her on fire. She sank shortly thereafter and the Anglo-French fleet withdrew.[26]

Jurien de la Gravière continued to operate with the main fleet after it enacted a blockade of the southern end of the Adriatic. On 18–19 September, the fleet made another incursion into the Adriatic, steaming as far north as the island of Lissa. The fleet continued these operations in October and November, including a sweep off the coast of Montenegro to cover a group of merchant vessels replenishing their coal there. Throughout this period, the battleships rotated through Malta or Toulon for periodic maintenance; Corfu became the primary naval base in the area.[27][28]

The patrols continued through late December, when an Austro-Hungarian U-boat torpedoed Jean Bart, leading to the decision by the French naval command to withdraw the main battle fleet from direct operations in the Adriatic. For the rest of the month, the fleet remained at Navarino Bay. The battle fleet thereafter occupied itself with patrols between Kythira and Crete; these sweeps continued until 7 May. Following the Italian entry into the war on the side of France, the French fleet handed control of the Adriatic operations to the Italian Regia Marina (Royal Navy) and withdrew its fleet to Malta and Bizerte, the latter becoming the main fleet base.[29][30]

1916–1918

In October 1916, Jurien de la Gravière served as Boué de Lapeyrère's flagship during a bombardment operation on the southern Anatolian coast of the Ottoman Empire.[27] The Greek government had remained neutral thus far in the conflict, since Constantine I's wife Sophie was the sister of the German Kaiser Wilhelm II. The French and British were growing increasingly frustrated by Constantine's refusal to enter the war, and sent the significant elements of the Mediterranean Fleet to try to influence events in the country. In August, a pro-Allied group launched a coup against the monarchy in the Noemvriana, which the Allies sought to support. Several French ships sent men ashore in Athens on 1 December to support the coup, but they were quickly defeated by the royalist Greek Army. In response, the British and French fleet imposed a blockade of the royalist-controlled parts of the country. Jurien de la Gravière was among the vessels sent to enforce the blockade. By June 1917, Constantine had been forced to abdicate.[27][31]

The French fleet, which had by then been relocated to a large anchorage at Corfu, remained largely immobilized due to shortages of coal, preventing training until late September 1918. During this period, the fleet's large ships had members of their crews transferred to destroyers and other anti-submarine patrol vessels. Coupled with the inaction of the fleet, these reductions seriously damaged the morale of those men who remained aboard the fleet's battleships and cruisers. In late October, members of the Central Powers began signing armistices with the British and French, signaling the end of the war.[32][33]

Postwar

After the war, Jurien de la Gravière served in the Syrian Division, along with two smaller vessels through early 1920. At that time, she served as the flagship of Rear Admiral Charles Mornet. After returning to France, she was struck from the naval register in 1922 and was thereafter sold to ship breakers.[34][35]

Footnotes

- Ropp, p. 284.

- Ropp, pp. 286–287.

- Gardiner, p. 313.

- Fisher, pp. 238–239.

- Ships, p. 326.

- Brassey & Leyland 1904, p. 10.

- Friedman, p. 221.

- Friedman, p. 345.

- Gardiner, pp. 312–313.

- Gardiner & Gray, p. 193.

- Brassey & Leyland 1903, p. 26.

- Garbett 1908, p. 85.

- Jordan & Caresse, p. 248.

- Garbett 1903, pp. 944–945.

- Fortier & Augustin, p. 4.

- Garbett 1904, p. 309.

- Brassey 1905, p. 42.

- Annual List, p. 375.

- Brassey 1911, p. 56.

- Earle, pp. 1117–1118.

- Jordan & Caresse, p. 241.

- Jordan & Caresse, p. 252.

- Jordan & Caresse, pp. 252, 254–255.

- Corbett, p. 68.

- Corbett, p. 88.

- Jordan & Caresse, pp. 254–257.

- Gardiner & Gray, p. 194.

- Jordan & Caresse, p. 257.

- Jordan & Caresse, p. 257–260.

- Halpern, p. 16.

- Jordan & Caresse, p. 269.

- Jordan & Caresse, pp. 274–279.

- Hamilton & Herwig, p. 181.

- Jordan & Caresse, p. 289.

- Gardiner & Gray, pp. 193–194.

References

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1905). "Chapter III: Comparative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 40–57. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1911). "Chapter III: Comparative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 55–62. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. & Leyland, John (1903). "Chapter II: The Progress of Foreign Navies". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 21–56. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. & Leyland, John (1904). "Chapter I: Progress of Navies". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 1–25. OCLC 496786828.

- Corbett, Julian Stafford (1920). Naval Operations: To The Battle of the Falklands, December 1914. I. London: Longmans, Green & Co. OCLC 174823980.

- Earle, Ralph, ed. (September 1912). "Professional Notes". United States Naval Institute Proceedings. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. 38 (3). ISSN 0041-798X.

- Fisher, Edward C., ed. (1969). "157/67 French Protected Cruiser Isly". Warship International. Toledo: International Naval Research Organization. VI (3): 238. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Fortier, Alcée & Augustin, James M. (1904). Centennial Celebration of the Louisiana Transfer, December, 1903. III. New Orleans: Louisiana Historical Society. OCLC 1041786628.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One: Guns, Torpedoes, Mines and ASW Weapons of All Nations; An Illustrated Directory. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Garbett, H., ed. (August 1903). "Naval Notes: France". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. London: J. J. Keliher & Co. XLVII (306): 941–946. OCLC 1077860366.

- Garbett, H., ed. (June 1904). "Naval Notes: France". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. London: J. J. Keliher & Co. XLVIII (316): 707–711. OCLC 1077860366.

- Garbett, H., ed. (January 1908). "Naval Notes: France". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. London: J. J. Keliher & Co. XLVII (299): 84–89. OCLC 1077860366.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

- Halpern, Paul G. (2004). The Battle of the Otranto Straits. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34379-6.

- Hamilton, Robert & Herwig, Holger, eds. (2004). Decisions for War, 1914–1917. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83679-1.

- Jordan, John & Caresse, Philippe (2017). French Battleships of World War One. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-639-1.

- Ropp, Theodore (1987). Roberts, Stephen S. (ed.). The Development of a Modern Navy: French Naval Policy, 1871–1904. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-141-6.

- "Ships". Journal of the American Society of Naval Engineers. Washington D.C.: R. Beresford. XIV (1): 282–368. February 1902.

- Thirty-Ninth Annual List of Merchant Vessels of the United States for the Year Ending June 30, 1906. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1907.