Forbin-class cruiser

The Forbin class was a group of three protected cruisers built for the French Navy in the late 1880s and early 1890s. The class comprised Forbin, Coëtlogon, and Surcouf. They were ordered as part of a fleet program that, in accordance with the theories of the Jeune École, proposed a fleet based on cruisers and torpedo boats to defend France. The Forbin-class cruisers were intended to serve as flotilla leaders for the torpedo boats, and they were armed with a main battery of four 138 mm (5.4 in) guns.

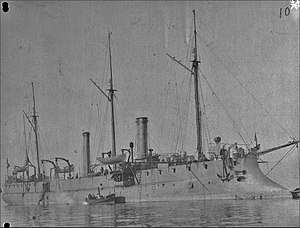

Coëtlogon underway | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Forbin class |

| Operators: |

|

| Preceded by: | Suchet |

| Succeeded by: | Troude class |

| Built: | 1886–1894 |

| In service: | 1889–1921 |

| Completed: | 3 |

| Retired: | 3 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Protected cruiser |

| Displacement: | 1,901–2,012 long tons (1,932–2,044 t) |

| Length: | 95 m (311 ft 8 in) lwl |

| Beam: | 9 m (29 ft 6 in) |

| Draft: | 5.23 m (17 ft 2 in) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 20 to 20.5 knots (37.0 to 38.0 km/h; 23.0 to 23.6 mph) |

| Complement: | 199 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: | Deck: 41 mm (1.6 in) |

Forbin spent most of her career in the Mediterranean in the Reserve Squadron, while Surcouf served in the Northern Squadron in the English Channel. Coëtlogon suffered from machinery problems that significantly delayed her completion, and after finally entering service in 1894, joined Surcouf in the Northern Squadron. All three ships were in reserve by 1901. Coëtlogon was discarded in 1906, while Forbin was converted into a collier in 1913. Surcouf was the only member of the class still in active service during World War I, and she was deployed later in the conflict to the Gulf of Guinea. Forbin was scrapped in 1919 and Surcouf was sold to ship breakers two years later.

Design

By the late 1870s, the unprotected cruisers and avisos the French Navy had built as fleet scouts were becoming obsolescent, particularly as a result of their low speed of 12 to 14 knots (22 to 26 km/h; 14 to 16 mph), which rendered them too slow to be effective scouts. Beginning in 1879, the Conseil des Travaux (Council of Works) had requested designs for small but fast cruisers of about 2,000 long tons (2,032 t) displacement that could be used as scouts for the main battle fleet or to lead squadrons of torpedo boats. The naval engineer Louis-Émile Bertin had advocated for just such a vessel since 1875, and his design became the cruiser Milan. Bertin's design was developed into what would become the Forbin-type of protected cruisers after the Conseil requested light armor protection for the ships.[1][2]

In the meantime, by 1886, Admiral Théophile Aube had become the French Minister of Marine. Aube was an ardent supporter of the Jeune École doctrine, which envisioned using a combination of cruisers and torpedo boats to defend France and attack enemy merchant shipping. By the time Aube had come to office, the French Navy had laid down three large protected cruisers that were intended to serve as commerce raiders: Sfax, Tage, and Amiral Cécille. His proposed budget called for another six large cruisers and ten smaller vessels, but by the time it was approved later in 1886, it had been modified to three large cruisers of the Alger class, along with the two medium cruisers Davout and Suchet, and six small cruisers, which became the Forbin and Troude classes, each with three members.[3][4]

Characteristics

The ships of the Forbin class were 95 m (311 ft 8 in) long at the waterline, with a beam of 9 m (29 ft 6 in) and a draft of 5.23 m (17 ft 2 in). They displaced 1,901 to 2,012 long tons (1,932 to 2,044 t). Their hulls featured pronounced ram bows and had a tumblehome shape. The ships were originally rigged with three light masts, though all but Surcouf had their mainmast removed later in their careers. The ships' superstructure was minimal, consisting primarily of a small bridge structure. In 1893, Surcouf received a small conning tower. Their crew amounted to 199 officers and enlisted men.[5]

The ship's propulsion system consisted of a pair of horizontal compound steam engines driving two screw propellers. Steam was provided by six coal-burning fire-tube boilers that were ducted into two funnels. Their machinery was rated to produce 5,800 indicated horsepower (4,300 kW) for a top speed of 20 to 20.5 knots (37.0 to 38.0 km/h; 23.0 to 23.6 mph). Coal storage amounted to 300 long tons (300 t). Later in their careers, Forbin and Surcouf had their boilers modified to accept mixed coal and oil fuel.[5]

The ships were armed with a main battery of four 138 mm (5.4 in) 30-caliber guns in individual pivot mounts, all in sponsons in the upper deck, with two guns per broadside. Forbin was originally completed with just two of the guns, but had the remaining pair installed later.[5] According to Norman Friedman, the guns were likely the Modèle 1884 version of the gun, though he notes that a 30-caliber Modèle 1893 variant also existed, and may have replaced the 1884 gun during the ships' careers. They were supplied with a variety of shells, including solid cast iron projectiles and explosive armor-piercing shells, both of which weighed 30 kg (66 lb). The guns fired with a muzzle velocity of 590 m/s (1,900 ft/s).[6]

For close-range defense against torpedo boats, they carried three 47 mm (1.9 in) 3-pounder Hotchkiss guns and four 37 mm (1.5 in) 1-pounder Hotchkiss revolver cannon. They were also armed with four 350 mm (14 in) torpedo tubes in her hull below the waterline, though Forbin and Surcouf later had their tubes removed. They had provisions to carry up to 150 naval mines.[5]

Armor protection consisted of a curved armor deck that was 41 mm (1.6 in) thick. Above the deck was a small a cofferdam to contain flooding. Below the deck and above the engine and boiler rooms was a thin anti-splinter deck to protect the machinery from shell fragments.[5]

Construction

Coëtlogon had serious problems with her propulsion system, which significantly delayed her completion. She began sea trials in 1891 that revealed the defects and led to a complete replacement of the engines. The new engines also had problems, including severe vibration,[5][7][8] and Coëtlogon was finally able to complete her trials and enter fleet service in 1895.[9]

| Name | Shipyard[5] | Laid down[5] | Launched[7] | Completed[5] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forbin | Arsenal de Rochefort, Rochefort | May 1886 | 14 January 1888 | February 1889 |

| Surcouf | Arsenal de Cherbourg, Cherbourg | May 1886 | October 1888 | 1890 |

| Coëtlogon | Ateliers et Chantiers de Saint-Nazaire Penhoët, Saint-Nazaire | 1887 | 3 December 1888 | August 1894 |

Service history

Forbin was initially placed in the Reserve Squadron, where she was activated periodically to participate in training exercises with the ships of the Mediterranean Squadron. Surcouf was assigned to the Northern Squadron in the English Channel; Coëtlogon joined her there after finally entering service in 1895. During this period, the ships were primarily occupied with training exercises; during one set of maneuvers in 1894, Forbin had to tow a torpedo boat back to port after it was damaged in a collision with another vessel.[10][11][12] Surcouf was placed in the 2nd category of reserve in 1896,[13] but she was reactivated the following year for exercises with the Northern Squadron.[14]

Surcouf remained in service with the Northern Squadron through 1899.[15] All three ships were reduced to reserve by 1901.[16] That year, Forbin suffered an ammunition fire that resulted from unstable Poudre B charges.[17] In 1902, Surcouf was deployed to East Asia,[18] and she returned to France by 1904 for another stint with the Northern Squadron.[19] She remained there through 1908.[20]

Forbin was reactivated in 1906 for service in the Northern Squadron,[21] while Coëtlogon, which was not a successful vessel, was struck from the naval register and broken up.[7] Forbin had been moved to the Moroccan Naval Division in 1911 and was converted into a collier two years later.[7] At some point during World War I, Surcouf was sent to the Gulf of Guinea to patrol for German vessels, remaining there until the end of the war.[22] Forbin was stuck in 1919 and scrapped, and Surcouf followed her to the breakers' yard two years later.[5][7]

Notes

- Ropp, pp. 129–130.

- Gardiner, p. 320.

- Gardiner, pp. 308–310.

- Ropp, pp. 158–159, 172.

- Gardiner, p. 309.

- Friedman, p. 221.

- Gardiner & Gray, p. 193.

- Dorn & Drake, p. 50.

- Brassey 1895a, p. 24.

- Brassey 1893, p. 70.

- Barry, pp. 208–212.

- Brassey 1895b, p. 50.

- Weyl, p. 96.

- Thursfield, pp. 140–143.

- Brassey 1899, p. 71.

- Jordan & Caresse 2017, p. 219.

- Jordan & Caresse 2017, p. 234.

- Brassey 1902, p. 51.

- Garbett, p. 709.

- Brassey 1908, p. 49.

- Brassey 1906, p. 39.

- Jordan & Caresse 2019, p. 227.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Forbin class cruisers. |

- Barry, E. B. (1895). "The Naval Manoeuvres of 1894". The United Service: A Monthly Review of Military and Naval Affairs. Philadelphia: L. R. Hamersly & Co. XII: 177–213. OCLC 228667393.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1893). "Chapter IV: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 66–73. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1895a). "Ships Building In France". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 19–28. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1895b). "Chapter III: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 49–59. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1899). "Chapter III: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 70–80. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1902). "Chapter III: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 47–55. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1906). "Chapter III: Comparative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 38–52. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1908). "Chapter III: Comparative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 48–57. OCLC 496786828.

- Dorn, E. J. & Drake, J. C. (July 1894). "Notes on Ships and Torpedo Boats". Notes on the Year's Naval Progress. Washington, D.C.: United States Office of Naval Intelligence. XIII: 3–78. OCLC 727366607.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One: Guns, Torpedoes, Mines and ASW Weapons of All Nations; An Illustrated Directory. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Garbett, H., ed. (June 1904). "Naval Notes: France". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. London: J. J. Keliher & Co. XLVIII (316): 707–711. OCLC 1077860366.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

- Jordan, John & Caresse, Philippe (2017). French Battleships of World War One. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-639-1.

- Jordan, John & Caresse, Philippe (2019). French Armoured Cruisers 1887–1932. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5267-4118-9.

- Ropp, Theodore (1987). Roberts, Stephen S. (ed.). The Development of a Modern Navy: French Naval Policy, 1871–1904. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-141-6.

- Thursfield, J. R. (1898). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). "II: French Naval Manoeuvres". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 138–143. OCLC 496786828.

- Weyl, E. (1896). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). "Chapter IV: The French Navy". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 61–72. OCLC 496786828.