French battleship Charles Martel

Charles Martel was a pre-dreadnought battleship of the French Navy built in the 1890s. She was laid down in August 1891, launched in August 1893, and commissioned into the fleet in June 1897. She was a member of a group of five broadly similar battleships ordered as part of the French response to a major British naval construction program. The five ships were built to the same basic design parameters, though the individual architects were allowed to deviate from each other in other details. Like her half-sisters—Carnot, Jauréguiberry, Bouvet, and Masséna—she was armed with a main battery of two 305 mm (12.0 in) guns and two 274 mm (10.8 in) guns. She had a top speed of 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph).

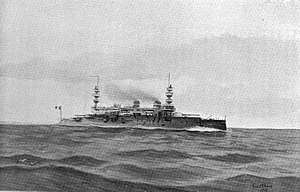

Illustration of Charles Martel underway | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Charles Martel |

| Namesake: | Charles Martel |

| Ordered: | 10 September 1890 |

| Builder: | Brest |

| Laid down: | 1 August 1891 |

| Launched: | 29 August 1893 |

| Commissioned: | June 1897 |

| Stricken: | 1922 |

| Fate: | Broken up in 1922 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Pre-dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement: | 11,880 t (11,690 long tons; 13,100 short tons) |

| Length: | 115.49 m (378.9 ft) |

| Beam: | 21.64 m (71.0 ft) |

| Draft: | 8.38 m (27.5 ft) |

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph) |

| Complement: | 644 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

Charles Martel spent her active career in the Mediterranean Squadron of the French fleet, first in the active squadron, and later in the Reserve Squadron. She regularly participated in fleet maneuvers, and in the 1901 exercises, the submarine Gustave Zédé hit her with a dummy torpedo, which caused a significant controversy in the French press. The ship was involved in an international squadron that intervened in the Cretan Revolt in 1897. Charles Martel spent just five years in the active squadron, having been surpassed by more modern battleships during a period of rapid developments in naval technology. She spent the years 1902–1914 in reserve, and in early 1914 the French Navy decided to discard the vessel. After the outbreak of World War I, however, the navy kept the ship in its inventory, though Charles Martel was not reactivated for service during the conflict. The ship was ultimately broken up in 1922.

Design

In 1889, the British Royal Navy passed the Naval Defence Act that resulted in the construction of the eight Royal Sovereign-class battleships; this major expansion of naval power led the French government to pass its reply, the Statut Naval (Naval Law) of 1890. The law called for a total of twenty-four "cuirasses d'escadre" (squadron battleships) and a host of other vessels, including coastal defense battleships, cruisers, and torpedo boats. The first stage of the program was to be a group of four squadron battleships that were built to different designs but met the same basic characteristics, including armor, armament, and displacement. The naval high command issued the basic requirements on 24 December 1889; displacement would not exceed 14,000 metric tons (14,000 long tons; 15,000 short tons), the primary armament was to consist of 34-centimeter (13 in) and 27 cm (11 in) guns, the belt armor should be 45 cm (18 in), and the ships should maintain a top speed of 17 knots (31 km/h; 20 mph). The secondary battery was to be either 14 cm (5.5 in) or 16 cm (6.3 in) caliber, with as many guns fitted as space would allow.[1]

The basic design for the ships was based on the previous battleship Brennus, but instead of mounting the main battery all on the centerline, the ships used the lozenge arrangement of the earlier vessel Magenta, which moved two of the main battery guns to single turrets on the wings.[2] Five naval architects submitted designs to the competition; the design that became Charles Martel was prepared by Charles Ernest Huin, who had also designed the ironclad battleship Hoche. Political considerations, namely parliamentary objections to increases in naval expenditures, led the designers to limit displacement to around 12,000 metric tons (12,000 long tons; 13,000 short tons). Huin submitted his finalized proposal in line with these considerations on 12 August 1890, and it was accepted and ordered on 10 September. Though the program called for four ships to be built in the first year, five were ultimately ordered: Charles Martel, Carnot, Jauréguiberry, Bouvet, and Masséna.[1]

An earlier vessel, also named Charles Martel, was laid down in 1884 and cancelled under the tenure of Admiral Théophile Aube. The vessel, along with a sister ship named Brennus, was a modified version of the Marceau-class ironclad battleships. After Aube's retirement, the plans for the ships were entirely redesigned, though the later pair of ships are sometimes conflated with the earlier, cancelled designs.[3] This may be due to the fact that both of the ships named Brennus were built in the same shipyard, and material assembled for the first vessel was used in the construction of the second.[4] The two pairs of ships were, nevertheless, distinct vessels.[5]

She and her half-sisters were disappointments in service; they generally suffered from stability problems, and Louis-Émile Bertin, the Director of Naval Construction in the late 1890s, referred to the ships as "chavirables" (prone to capsizing). All five of the vessels compared poorly to their British counterparts, particularly their contemporaries of the Majestic class. The ships suffered from a lack of uniformity of equipment, which made them hard to maintain in service, and their mixed gun batteries comprising several calibers made gunnery in combat conditions difficult, since shell splashes were hard to differentiate. Many of the problems that plagued the ships in service were a result of the limitation on their displacement, particularly their stability and seakeeping.[6]

General characteristics and machinery

Charles Martel was 115.49 meters (378 ft 11 in) long between perpendiculars, and had a beam of 21.64 m (71 ft 0 in) and a draft of 8.38 m (27 ft 6 in). She had a displacement of 11,880 tonnes (11,692 long tons). Her forecastle gave her a high freeboard forward, but her quarterdeck was cut down to the main deck level aft. Her hull was given a marked tumblehome to give the 27 cm guns wide fields of fire. Like earlier Huin designs, Charles Martel had a very tall superstructure; she was equipped with two heavy military masts, with a tall flying deck between them. In service, the tall superstructure made her top-heavy, though her high freeboard made her very seaworthy. She had a crew of 644 officers and enlisted men.[7][8]

Charles Martel had two vertical, three-cylinder triple expansion engines manufactured by Schneider-Creusot; each engine drove a single screw, with steam supplied by twenty-four Lagrafel d'Allest water-tube boilers. The boilers were divided into four boiler rooms and were ducted into two funnels. Her propulsion system was rated at 13,500 indicated horsepower (10,100 kW), which allowed the ship to steam at a speed of 17 knots (31 km/h; 20 mph) normally and up to 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph) with forced draft. On a four-hour speed test on her sea trials, Charles Martel reached 14,931 ihp (11,134 kW). As built, she could carry 650 t (640 long tons; 720 short tons) of coal, though additional space allowed for up to 980 t (960 long tons; 1,080 short tons) in total.[7][9][10]

Armament and armor

Charles Martel's main armament consisted of two Canon de 305 mm Modèle 1887 guns in two single-gun turrets, one each fore and aft. She also mounted two Canon de 274 mm Modèle 1887 guns in two single-gun turrets, one amidships on each side, sponsoned out over the tumblehome of the ship's sides. Her secondary armament consisted of eight Canon de 138.6 mm Modèle 1888 guns, which were mounted in single turrets at the corners of the superstructure.[7][11]

Light armament for defense against torpedo boats consisted of eight Canon de 65 mm Modèle 1891 quick-firing guns on the shelter deck amidships and forward and aft of the superstructure, twelve 47 mm Modèle 1885 quick-firing guns, and eight 37 mm revolving cannon. Her armament suite was rounded out by four 450 mm (18 in) torpedo tubes, two of which were submerged in the ship's hull, with the other two in trainable deck mounts.[7][11]

The ship's armor was constructed with nickel steel that was manufactured by Schneider-Creusot. The main belt was 46 cm (18 in) thick amidships where it protected the ammunition magazines and propulsion machinery spaces, and tapered down to 25 cm (9.8 in) at the lower edge. On either end of the central citadel, the belt was reduced to 30.5 cm (12.0 in) at the waterline and 25 cm on the lower edge; the belt extended for the entire length of the hull. Above the belt was a 10 cm (3.9 in) thick strake side armor that created a highly-subdivided cofferdam to reduce the risk of flooding from battle damage. Coal storage bunkers were placed behind the upper side armor to increase its strength[7][12]

The main battery guns were protected with 38 cm (15 in) of armor, and the secondary turrets had 10 cm thick sides. The main armored deck was 7 cm (2.8 in) thick, below which were two layers of 1 cm (0.39 in) plating. Above the machinery spaces, a splinter deck that was 2.5 cm (0.98 in) thick was added. The conning tower had 23 cm (9.1 in) thick sides.[7][13]

Service history

Active career

Charles Martel was laid down on 1 August 1891 and launched on 29 August 1893. After completing fitting-out work, she began sea trials in 1896. She was commissioned into the French Navy in June 1897.[12] She was delayed in completing her sea trials, as her boiler tubes had to be replaced with a safer, weld-less design, following an accident aboard Jauréguiberry with her welded tubes. Following her commissioning for service, she was assigned to the Mediterranean Squadron.[14] Immediately on entering service, she and her half-sisters Carnot and Jauréguiberry were sent to join the International Squadron that had been assembled beginning in February. The multinational force also included ships of the Austro-Hungarian Navy, the Imperial German Navy, the Italian Regia Marina, the Imperial Russian Navy, and the British Royal Navy, and it was sent to intervene in the 1897–1898 Greek uprising on Crete against rule by the Ottoman Empire.[15]

In 1900, she became the flagship of Contre-amiral (Rear Admiral) Roustan, the commander of the Second Division of the Mediterranean Squadron. On 6 March, Charles Martel joined the battleships Brennus, Gaulois, Charlemagne, Bouvet, and Jauréguiberry and four protected cruisers for maneuvers off Golfe-Juan, including night firing training. Over the course of April, the ships visited numerous French ports along the Mediterranean coast, and on 31 May the fleet steamed to Corsica for a visit that lasted until 8 June. During the fleet maneuvers held that June, Charles Martel led Group II, which included four cruisers and a pair of destroyers, again under Roustan's command. The exercises included a blockade of Group III's battleships by Group II. The Mediterranean Fleet then assembled with the Northern Squadron off the coast of Portugal before proceeding to Quiberon Bay for joint maneuvers in July. The maneuvers concluded with a naval review in Cherbourg on 19 July for President Émile Loubet. On 1 August, the Mediterranean Fleet departed for Toulon, arriving on 14 August. The year 1901 passed uneventfully for Charles Martel, except for the fleet maneuvers conducted that year.[16] During the exercises, Charles Martel was hit by a training torpedo fired by the submarine Gustave Zédé, which created an uproar in the press.[17]

Reserve fleet

During mid-1902, Charles Martel was transferred to the Division de réserve (Reserve Division) of the Mediterranean Fleet, along with the battleships Brennus, Carnot, and Hoche and the three armored cruisers Pothuau, Amiral Charner, and Bruix.[18][19] She initially served as the flagship of Contre-amiral Besson, though by July 1903 her place as flagship had been taken by the battleship Saint Louis. During this period in reserve, ships were frequently reactivated for short periods as active vessels had to be taken into dock for maintenance.[20] She remained in the Reserve Squadron, which was renamed the Second Squadron in 1906; by that time, she was in the Second Division of the Squadron, under the command of Contre-amiral Germinet.[21] On 16 September, she was present for a major fleet review in Marseilles that saw visits from British, Spanish, and Italian squadrons.[22] The ship was maintained in a state of en disponibilité armée, a state of reduced readiness with a minimal crew.[23] Charles Martel was in full commission for three months of the year, and in reserve with a reduced crew for the remainder.[24] She remained in this status for the duration of 1907.[25]

In 1909, the Mediterranean Fleet was reorganized, since by then the six République and Liberté-class battleships had entered service. This allowed for the creation of a second battle squadron, and on 5 January 1910, Charles Martel was assigned to it. When the Danton-class battleships began entering service in 1911, the fleet was reorganized again, with Charles Martel and the other older ships being transferred to the new 3rd Battle Squadorn on 5 October, which was based in Brest. At this time, she served as the flagship of Contre-amiral Adam, the commander of the 2nd Division of the 3rd Squadron. The ship was present for another naval review off Toulon on 4 September 1911. On 1 March 1912, Charles Martel was reduced to reserve status.[26]

In early 1914, the French Naval Minister Ernest Monis decided to discard Charles Martel, owing to the cost of maintaining the obsolete battleship, which was by then nearly twenty years old.[27] By the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, Charles Martel had been laid up in the port of Brest, along with Carnot. Both ships were retained on the effective list, however, pending the completion of the new Normandie-class battleships.[28] Charles Martel was ultimately stricken from the naval register in 1922 and sold for scrapping that year.[7]

Footnotes

- Jordan & Caresse, pp. 22–23.

- Ropp, p. 223.

- Ropp, p. 222.

- Brassey 1889, p. 65.

- Gardiner, p. 283.

- Jordan & Caresse, pp. 32, 38–40.

- Gardiner, p. 293.

- Jordan & Caresse, pp. 25–26, 28.

- Cooper, pp. 802–803.

- Jordan & Caresse, pp. 27–28.

- Jordan & Caresse, p. 27.

- Jordan & Caresse, p. 26.

- Jordan & Caresse, pp. 26–27.

- Brassey 1898, p. 26.

- Robinson, pp. 186–187.

- Jordan & Caresse, pp. 217–219.

- Compton-Hall, p. 133.

- "Naval & Military intelligence". The Times (36764). London. 10 May 1902. p. 8.

- Brassey 1903, pp. 57, 59.

- Jordan & Caresse, p. 223.

- Journal of the Royal United Service Institution, p. 474.

- Jordan & Caresse, pp. 223–224.

- Journal of the Royal United Service Institution, p. 88.

- Journal of the Royal United Service Institution, p. 729.

- Palmer, p. 171.

- Jordan & Caresse, pp. 232, 239.

- Gill, p. 505.

- Preston, p. 29.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles Martel (ship, 1893). |

- Brassey, Thomas A., ed. (1889). The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A., ed. (1898). The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A., ed. (1903). The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co. OCLC 496786828.

- Caresse, Philippe (2020). "The Fleet Battleship Charles Martel". In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2020. Oxford: Osprey. pp. 135–151. ISBN 978-1-4728-4071-4.

- Compton-Hall, Richard (2004). First Submarines: The Beginnings of Underwater Warfare. Penzance: Periscope Publishing. ISBN 978-1904381198.

- Cooper, George F., ed. (1898). "French Battleship "Charles Martel"". Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute. XXIV (4): 802–803. ISSN 0041-798X.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One: Guns, Torpedoes, Mines and ASW Weapons of All Nations; An Illustrated Directory. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Jordan, John & Caresse, Philippe (2017). French Battleships of World War One. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-639-1.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. Greenwich: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-8317-0302-8.

- Gill, C. C. (1914). "Professional Notes". Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute. 40: 475–618. ISSN 0041-798X.

- Palmer, W., ed. (1908). "France". Hazell's Annual. London: Hazell, Watson & Viney, Ltd. OCLC 852774696.

- Preston, Antony (1972). Battleships of World War I: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Battleships of All Nations, 1914–1918. New York: Galahad Books. ISBN 0883653001.

- Robinson, Charles N., ed. (1897). "The Fleets of the Powers in the Mediterranean". The Navy and Army Illustrated. London: Hudson & Kearnes. III: 186–187. OCLC 7489254.

- Ropp, Theodore (1987). Roberts, Stephen S. (ed.). The Development of a Modern Navy: French Naval Policy, 1871–1904. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-141-6.

- "Naval Notes". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. London: J. J. Keliher & Co. Ltd. LI. 1907. OCLC 1077860366.