Fort Vancouver National Historic Site

Fort Vancouver National Historic Site is a United States National Historic Site located in the states of Washington and Oregon. The National Historic Site consists of two units, one located on the site of Fort Vancouver in modern-day Vancouver, Washington; the other being the former residence of John McLoughlin in Oregon City, Oregon. The two sites were separately given national historic designation in the 1940s.[4] The Fort Vancouver unit was designated a National Historic Site in 1961, and was combined with the McLoughlin House into a unit in 2003.

| Fort Vancouver National Historic Site | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Illustration of Fort Vancouver and its environs in 1855 | |

| Location | Vancouver, Washington and Oregon City, Oregon, USA |

| Nearest city | Vancouver, Washington, and Oregon City, Oregon |

| Coordinates | 45°37′31″N 122°39′29″W[1] |

| Area | 207 acres (84 ha)[2] |

| Established | June 19, 1948 (national monument) June 30, 1961 (national historic site) |

| Visitors | 710,439 (in 2011)[3] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Fort Vancouver National Historic Site |

Visitor Center

The visitor center at Fort Vancouver National Historic Site was originally built in 1966 as a part of the National Park Service's Mission 66 Program. Today, the visitor center is co-operated by the both the National Park Service and the United States Forest Service. Recent renovations to the visitor center (2015) transformed the historic building as an information center for both Fort Vancouver National Historic Site and the Gifford Pinchot National Forest.[5] The visitor center features rotating archaeological exhibits from the national historic site and art exhibits from local native artists.[6] The building also has a theater that shows 2 films from the National Park Service and the United States Forest Service: Oregon Experience: Fort Vancouver (25mins), and Mount St. Helens - Eruption of Life (17mins).

HBC Fort Vancouver site

The main unit of the site, containing Fort Vancouver, is located in Vancouver, Washington, just north of Portland, Oregon. Fort Vancouver was an important Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) fur trading post that was established in 1824. Operations until 1845 were overseen by Chief Factor John McLoughlin. It was the headquarters of the Hudson's Bay Company's fur trade activity on the Pacific coast and its influence stretched from the Rocky mountains in the east, to Alaska in the north, Alta California in the south, and to the Kingdom of Hawaii in the Pacific. Ratified in 1846, the Treaty of Oregon was signed by the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the United States, thereby ending the decades long Oregon boundary dispute. The treaty permitted the Hudson's Bay Company to continue to operate at Fort Vancouver, which was now within the Oregon Territory. On June 14, 1860, Fort Vancouver was abandoned by the Hudson's Bay Company in favor of their stations in British Columbia, such as Fort Victoria.

In 1849, the United States Army constructed the Vancouver Barracks adjacent to the British trading post; and took over the facility when it was abandoned. A fire destroyed the Hudson's Bay Company fort in 1866, but the Army facility continued in operation in various forms until the present. Fort Vancouver was separated from the Army's barracks and became a national monument in 1948. Congress expanded the protected area in 1966 and re-designated the site as a National Historic Site. For some years after its addition to the National Park System, the National Park Service was reluctant to begin reconstruction of the fort walls or buildings, preferring to manage it as an archaeological site as provided by its standing policies. However, in 1965, with the urging of the local community, Congress directed reconstruction to begin. All fort structures seen today are modern replicas, albeit carefully placed on the original locations.[7] In response to concerns about the designation of reconstructed structures, the Park Service designated the Vancouver National Historic Reserve Historic District to encompass reconstructed buildings as well as historic Army and Mission 66 era Park Service structures.[8]

The National Park Service also operates the Pearson Air Museum on the fort grounds. An earth-covered pedestrian land bridge was built over the Lewis and Clark Highway, as part of the Confluence Project, in 2007. It connects the site with the Columbia River.[9]

McLoughlin House site

McLoughlin House National Historic Site | |

U.S. National Historic Site | |

| |

| |

| Location | McLoughlin Park, between 7th and 8th Sts., Oregon City, Oregon |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 45°21′26″N 122°36′21″W |

| Area | 0.6 acres (0.24 ha) |

| Built | 1845 |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000637[10] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

| Designated NHS | 1941 |

The McLoughlin House unit consists of the homes of McLoughlin, and of Dr. Forbes Barclay, an explorer and associate of McLoughlin's; the two homes are known respectively as the McLoughlin House and the Barclay House. They are located adjacent to each other on a bluff overlooking the Willamette River in Oregon City, Oregon, on a plot of land set aside for public use by McLoughlin in the 1840s.[11]

In 1846, McLoughlin left the employ of Hudson's Bay Company, and purchased from the company a land claim located on the Willamette River in Oregon City. McLoughlin constructed the house there, and lived there until his death in 1857.[12] The house, a two-style colonial mansion, is typical of East Coast residences from the time.[13]

After McLoughlin's death in 1857, his widow lived there until she died three years later; their heirs sold the house in 1867. The home soon became a bordello known as the Phoenix Hotel. In 1908, the paper mill that owned the property wished to expand and the house was threatened with demolition, but preservationists saved it the next year, raising over $1,000 and overcoming a referendum.[14] In 1910 the house was moved from the riverfront to its current location on a bluff overlooking downtown Oregon City. It sat there for twenty-five years, until being restored in 1935-1936 under the auspices of the Civil Works Administration, and opened as a museum.[13]

The Barclay House was built in 1849 by Portland carpenter and pioneer John L. Morrison, and occupied by Dr. Barclay and his family. Barclay died in 1874; the house remained in the family's possession until 1930 when it was moved from the waterfront to its present location, next to the McLoughlin House. Today, the Barclay House contains museum offices and a gift shop.[15]

The McLoughlin House became a National Historic Site in 1941, and both homes were added to the National Park System in 2003, becoming part of the Fort Vancouver National Historic Site.[12][16] The McLoughlin House unit lies on the Oregon National Historic Trail, a part of the National Trails System. The graves of McLoughlin and his wife are on the premises.[17] The house contains both original and period furnishings.

Pearson Air Museum

Opened in a historic hangar in 1996, the Pearson Air Museum and The Jack Murdock Aviation Center showcases aviation history in the Vancouver area, and specifically Pearson Airfield. Today, the Pearson Air museum displays a number of aircraft, including a De Havilland DH-4 Liberty[18] that has been restored to represent an aircraft from the US Army Air Corps 321st Observation Squadron that was stationed at Pearson Airfield in the 1930s. In June 2018, National Park Service Volunteers completed work on a replica of Silas Christofferson's Curtis Pusher from scratch. The original plane was flown from the roof of the Multnomah Hotel in Portland, OR to the location of the modern day Pearson airfield. The replica is currently being exhibited at the Pearson Air Museum. Exhibits at the museum also feature the US Army Spruce Production Division,[19] and the first transpolar flight which landed in 1937 on Pearson Field from Moscow, Russia. Models of the Russian Tupolev ANT-25 that made the first transpolar flight are on display at the museum.[20]

Vancouver Barracks

Parts of the Vancouver Barracks were transferred to the National Park Service in 2012 when the US Army Reserve officially closed the post after its continuous occupation since 1849.

From the National Park Service Website:

"While many of the buildings are closed to the public, wayside exhibits throughout the barracks share the history of this military post. "[21]

Since the Post to Park transfer to the National Park Service in 2012, the NPS has been restoring and renovating the barracks buildings to be used as mixed-use structures. Future tenants of these buildings are expected to be other governmental agencies, community groups, and private businesses. The area is expected to feature a community center, office buildings, restaurants, and retail in addition to a future museum space for the Vancouver Barracks operated by the National Park Service. In 2016, the Gifford Pinchot National Forest of the USDA National Forest Service moved its headquarters and administration operations to one of the renovated double infantry barracks buildings in the Vancouver Barracks.[22] The United States Forest Service co-operates the visitor center on Fort Vancouver National Historic Site along with the National Park Service.[5]

Recreation

A cross country running course is located at the site. The USA Cross Country Championships have been held at this site.[23]

Gallery

The master bedroom of the McLoughlin House

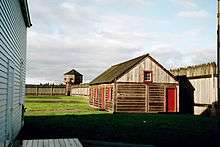

The master bedroom of the McLoughlin House Reconstructed buildings and palisade wall on the site of Fort Vancouver

Reconstructed buildings and palisade wall on the site of Fort Vancouver Children's beds in the Douglas apartment of the Chief Factor's House

Children's beds in the Douglas apartment of the Chief Factor's House

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fort Vancouver National Historic Site. |

- Officers Row, a district of historic U.S. Army structures adjacent to Fort Vancouver National Historic Site

- Pearson Field, adjacent to Fort Vancouver and a component of the National Historic Reserve

- Fort Langley National Historic Site, a preserved HBC fort in British Columbia

References

- "Fort Vancouver National Historical Site". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- "Listing of acreage as of December 31, 2011". Land Resource Division, National Park Service.

- "NPS Annual Recreation Visits Report". National Park Service.

- "Fort Vancouver: Cultural Landscape Report". National Park Service. Retrieved 2007-10-23.

- "Gifford Pinchot National Forest Headquarters and Visitor Services Moving to Fort Vancouver NHS in March - Fort Vancouver National Historic Site (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- "Fort Vancouver Visitor Center to Re-Open - Fort Vancouver National Historic Site (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- "Fort Vancouver National Historic Site: Draft General Management Plan". National Park Service. October 2002. Retrieved 2007-10-28..

- "HBCo. Blacksmith Shop". List of Classified Structures. National Park Service. 2008-11-18. Archived from the original on 2011-05-21. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- Raymond, Camela (November 2007). "The Shape of Memory". Portland Monthly.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- "McLoughlin House". End of the Oregon Trail.

- "The McLoughlin Memorial Association". Retrieved 2007-10-26.

- Engeman, Richard (2005). "Residence of Dr. John McLoughlin, Oregon City". Oregon History Project. Oregon Historical Society. Archived from the original on February 19, 2013.

- Holman, Frederick V. (1909). "Dedication of the McLoughlin Home". Oregon Historical Quarterly. 10.

- "Barclay House". The McLoughlin Memorial Association. Archived from the original on 2009-02-17. Retrieved 2007-10-26.

- PL 108–63, July 29, 2003, 117 Stat. 872, accessed at "U.S. Code Collection". Cornell University Law School, Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 2007-10-27.

- "Fort Vancouver National Historic Site - McLoughlin House". National Park Service. Retrieved 2007-10-23.

- "The DH-4 Liberty Plane at War and in Peace (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- "The Spruce Production Division (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- "Pearson Field and Pearson Air Museum - Fort Vancouver National Historic Site (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- "Vancouver Barracks - Fort Vancouver National Historic Site (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- "Historic Vancouver Barracks Building 987 Undergoes Rehabilitation (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- "Fort Vancouver National Historic Site". visitvancouverusa.com. Retrieved 2018-09-05.

External links

- National Park Service: Fort Vancouver National Historic Site

- Aviation: From Sand Dunes to Sonic Booms, a National Park Service Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. OR-2, "John McLoughlin House, McLoughlin Park (moved from Second & Third Streets), Oregon City, Clackamas County, OR", 2 photos, 3 data pages