Forced conversions of Muslims in Spain

The forced conversions of Muslims in Spain were enacted through a series of edicts outlawing Islam in the lands of the Spanish Monarchy. This effort was overseen by three Spanish kingdoms during the early 16th century: the Crown of Castile in 1500–1502, followed by Navarre in 1515–1516, and lastly the Crown of Aragon in 1523–1526.[1]

After Christian kingdoms finished their reconquest of Al-Andalus on 2 January 1492, the Muslim population stood between 500,000 and 600,000 people. At this time Muslims who lived under Christian rule were given the status of Mudéjar, legally allowing the open practice of Islam. In 1499, the Archbishop of Toledo, Cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros began a campaign in the city of Granada to force religious compliance with Christianity with torture and imprisonment; this triggered a Muslim rebellion. The rebellion was eventually quelled and then used to justify revoking the Muslims' legal and treaty protections. Conversion efforts were redoubled, and by 1501, officially, no Muslim remained in Granada. Encouraged by the success in Granada, the Castile's Queen Isabella issued an edict in 1502 which banned Islam for all of Castile. With the annexation of the Iberian Navarre in 1515, more Muslims still were forced to observe Christian beliefs under the Castilian edict. The last realm to impose conversion was the Crown of Aragon, whose kings had previously been bound to guarantee the freedom of religion for its Muslims under an oath included in their coronations. In the early 1520s, an anti-Islam uprising known as the Revolt of the Brotherhoods took place, and Muslims under the rebel territories were forced to convert. When the Aragon royal forces, aided by Muslims, suppressed the rebellion, King Charles I (better known as Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire) ruled that those forcible conversions were valid; thus, the "converts" were now officially Christians. This placed the converts under the jurisdiction of the Spanish Inquisition. Finally, in 1524, Charles petitioned Pope Clement VII to release the king from his oath protecting Muslims' freedom of religion. This granted him the authority to officially act against the remaining Muslim population; in late 1525, he issued an official edict of conversion: Islam was no longer officially extant throughout Spain.

While adhering to Christianity in public was required by the royal edicts and enforced by the Spanish Inquisition, evidence indicated that most of the forcibly converted (known as the "Moriscos") clung to Islam in secret. In daily public life, traditional Islamic law could no longer be followed without persecution by the Inquisition; as a result, the Oran fatwa was issued to acknowledge the necessity of relaxing sharia, as well as detailing the ways in which Muslims were to do so. This fatwa become the basis for the crypto-Islam practiced by the Moriscos until their expulsions in 1609–1614. Some Muslims, many near the coast, emigrated in response to the conversion. However, restrictions placed by the authorities on emigration meant leaving Spain was not an option for many. Rebellions also broke out in some areas, especially those with defensible mountainous terrain, but they were all unsuccessful. Ultimately, the edicts created a society in which devout Muslims who secretly refused conversion coexisted with former Muslims who became genuine practicing Christians, up until the expulsion.

Background

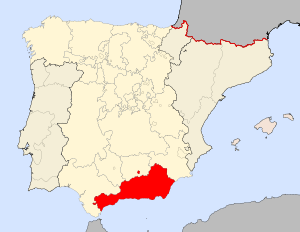

Islam has been present in the Iberian Peninsula since the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in the eighth century. At the beginning of the twelfth century, the Muslim population in the Iberian Peninsula – called "Al-Andalus" by the Muslims – was estimated to number as high as 5.5 million; among these were Arabs, Berbers and indigenous converts.[2] In the next few centuries, as the Christians pushed from the north in a process called reconquista, the Muslim population declined.[3] At the end of the fifteenth century, the Reconquista culminated in the fall of Granada, with the Muslim population of Spain estimated to be between 500,000 and 600,000 out of a total Spanish population of 7 to 8 million.[2] Approximately half of the Muslims lived in the former Emirate of Granada, the last independent Muslim state in the Iberian Peninsula, which had been annexed by the Crown of Castile.[2] About 20,000 Muslims lived in other territories of Castile, and most of the remainder lived in the territories of the Crown of Aragon.[4] These Muslims living under Christian rule were known as the Mudéjars.

In the initial years after the conquest of Granada, Muslims in Granada and elsewhere continued to enjoy freedom of religion.[1] This right was guaranteed in various legal instruments, including treaties, charters, capitulations, and coronation oaths.[1] For example, the Treaty of Granada (1491) guaranteed religious tolerance to the Muslims of the conquered Granada.[5] Kings of Aragon, including King Ferdinand II and Charles V, swore to protect the Muslims' religious freedom in their oaths of coronation.[6][7]

Three months after the conquest of Granada, in 1492, the Alhambra Decree ordered all Jews in Spain to be expelled or converted; this marked the beginning of a set of new policies.[8] In 1497, Spain's western neighbor Portugal expelled its Jewish and Muslim populations, as arranged by Spain's cardinal Cisneros in exchange for a royal marriage contract.[9] Unlike the Jews, Portuguese Muslims were allowed to relocate overland to Spain, and most did.[10]

Conversion process

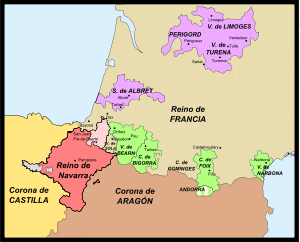

In the beginning of the sixteenth century, Spain was split between two realms: Crown of Castile and the smaller Crown of Aragon. The marriage between King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile united the two crowns, and ultimately their grandson Charles would inherit both crowns (as Charles I of Spain, but better known as Charles V, per his regnal number as Holy Roman Emperor). Despite the union, the lands of the two crowns functioned very differently, with disparate laws, ruling priorities, and treatment of Muslims.[11] There were also Muslims living in the Kingdom of Navarre, which was initially independent but was annexed by Castile in 1515.[12] Forced conversion varied in timeline by ruling body: it was enacted by the Crown of Castile in 1500–1502, in Navarre in 1515–1516, and by the Crown of Aragon in 1523–1526.[1]

In the Crown of Castile

Kingdom of Granada

Initial efforts at forcing the conversions of Spanish Muslims were started by Cardinal Cisneros, the archbishop of Toledo, who arrived in Granada in the autumn of 1499.[13] In contrast to Granada's own archbishop Hernando de Talavera, who had friendly relations with the Muslim population and relied on a peaceful approach towards conversions,[14] Cisneros adopted harsh and authoritarian measures.[14] He sent uncooperative Muslims, especially noblemen, to prison where they were treated severely (including reports of torture) until they converted.[15][16] Cisneros ignored warnings from his council that these methods might violate the Treaty of Granada, which guaranteed the Muslims freedom of religion.[15] Instead, he intensified his efforts, and in December he wrote to Pope Alexander VI that he converted 3,000 Muslims in a single day.[15]

The forced conversions led to a series of rebellions, initially started in the city of Granada. This uprising was precipitated by the riotous murder of a constable who had been transporting a Muslim woman for interrogation through the Muslim quarter of Granada; it ended with negotiations, after which the Muslims laid down their weapons and handed over those responsible for the murder of the constable.[17] Subsequently, Cisneros convinced King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella that by attempting a rebellion, the Muslims lost their rights in the treaty, and must now accept conversions.[17][18] The monarchs sent Cisneros back to Granada to preside over a renewed conversion campaign.[17][18] Muslims in the city were forcibly converted in large numbers – 60,000 according to the Pope, in a letter to Cisneros in March 1500.[18] Cisneros declared in January 1500 that "there is no one in the city who is not a Christian."[17]

Although the city of Granada was now under Christian control, the uprising spread to the Granadan countryside. The leader of the rebellion fled to the Alpujarra mountains in January 1500. Fearing that they would also be forced to convert, the population there quickly rose up in insurrection.[19] However, after a series of campaigns in 1500–01 in which 80,000 Christian troops were mobilized and King Ferdinand personally directed some operations, the rebellion was defeated.[20][19] The terms of surrender of the defeated rebels generally required them to accept baptism.[19][21] By 1501, not a single unconverted Muslim remained in Granada.[22]

Rest of Castile

Unlike the Muslims of Granada, who were under Muslim rule until 1492, Muslims in the rest of Castile had lived under Christian rule for generations.[23] Following the conversions in Granada, Isabella decided to impose a conversion-or-expulsion decree against the Muslims.[24] Castile outlawed Islam in legislation dated July 1501 in Granada, but it was not immediately made public.[22] The proclamation took place on February 12, 1502, in Seville (called the "key date" of this legislation by historian L. P. Harvey), and then locally in other towns.[22] The edict affected "all kingdoms and lordships of Castile and Leon".[22] According to the edict, all Muslim males aged 14 or more, or females aged 12 or more, should convert or leave Castile by the end of April 1502.[25] Both Castile-born Muslims and immigrants were subject to the decree, but slaves were excluded in order to respect the rights of their owners.[22] The edict justified the decision by saying that after the successful conversion of Granada, allowing Muslims in the rest of Castile would be scandalous, even though it acknowledged that these Muslims were peaceful. The edict also argued that the decision was needed to protect those who accepted conversion from the influence of the non-converted Muslims.[22]

On paper, the edict ordered expulsion rather than a forced conversion, but it forbade nearly all possible destinations; in reality, the Castilian authorities preferred Muslims to convert than emigrate.[26] Castile's western neighbor Portugal had already banned Muslims since 1497.[27] The order explicitly forbade going to other neighboring regions, such as the Kingdoms of Aragon and Valencia, the Principality of Catalonia, and the Kingdom of Navarre.[22] Of possible overseas destination, North Africa and territories of the Ottoman Empire were also ruled out.[22] The edict allowed travel to Egypt, then ruled by the Mamluk Sultanate, but there were few ships sailing between Castile and Egypt in those days.[28] It designated Biscay in the Basque country as the only port where the Muslims could depart, which meant that those from the south (such as Andalusia) would have to travel the entire length of the peninsula.[25] The edict also set the end of April 1502 as the deadline, after which Islam would become outlawed and those harboring Muslims would be punished severely.[28] A further edict issued on September 17, 1502, forbade the newly converted Muslims to leave Castile within the next two years.[25]

Historian L.P. Harvey wrote that with this edict, "in such a summary fashion, at such short notice", Muslim presence under the Mudéjar status came to an end.[28] Unlike in Granada, there were few surviving records of events such as mass baptisms, or how the conversions were organized.[28] There are records of Christian celebrations following the conversions, such as a "fairly elaborate festivity" involving a bullfight in Ávila.[28]

In Navarre

Navarre's queen Catherine de Foix (r. 1483–1517) and her co-ruling husband John III had no interest in pursuing expulsion or forced conversions.[12] When the Spanish Inquisition arrived in Navarre in the late fifteenth century and began harassing local Muslims, the Navarran royal court warned it to cease.[12]

However, in 1512, Navarre was invaded by Castile and Aragon.[12] The Spanish forces led by King Ferdinand quickly occupied the Iberian half of the kingdom, including the capital Pamplona; in 1513, he was proclaimed King.[12] In 1515, Navarre was formally annexed by the Crown of Castile as one of its kingdoms.[12] With this conquest, the 1501–02 edict of conversion came into effect in Navarre, and the Inquisition was tasked with enforcing it.[12] Unlike in Castile, however, few Muslims appeared to accept the conversion.[12] Historian Brian A. Catlos argues that the lack of baptismal records and a high volume of land sales by Muslims in 1516 indicate that most of them simply left Navarre to escape through the lands of the Crown of Aragon to North Africa (the Crown of Aragon was by this time inhospitable to Muslims).[12] Some also stayed despite the order; for example, in 1520, there were 200 Muslims in Tudela who were wealthy enough to be listed in the registers.[12]

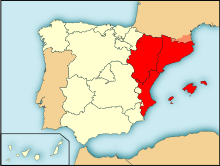

In the Crown of Aragon

Despite presiding over the conversions of Muslims in his wife's Castilian lands, Ferdinand II did not extend the conversions to his Aragonese subject.[29] Kings of Aragon, including Ferdinand, were required to swear an oath of coronation to not forcibly convert their Muslim subjects.[6] He repeated the same oath to his Cortes (assembly of estates) in 1510, and throughout his life, he was unwilling to break it.[30] Ferdinand died in 1516, and was succeeded by his grandson Charles V, who also swore the same oath at his coronation.[30]

The first wave of forced conversions in the Crown of Aragon happened during the Revolt of the Brotherhoods. Rebellion bearing an anti-Muslim sentiment broke out among the Christian subjects of Valencia in the early 1520s,[31] and those active in it forced Muslims to become Christians in the territories they controlled.[32] Muslims joined the Crown in suppressing the rebellion, playing crucial roles in several battles.[32] After the rebellion was suppressed, the Muslims regarded the conversions forced by the rebels as invalid and returned to their faith.[33] Subsequently, King Charles I (also known as Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire) started an investigation to determine the validity of the conversions.[34] The commission tasked with this investigation started working in November 1524.[35] Charles ultimately upheld the conversions, putting the forcibly converted subjects under the authority of the Inquisition.[34] Supporters of this decision argued that the Muslims had a choice when confronted by the rebels: they could have chosen to refuse and die, but did not, indicating that the conversions happened out of free will and must remain in effect.[32]

At the same time, Charles tried to release himself from the oath he swore to protect the Muslims.[36] He wrote to Pope Clement VII in 1523 and again in 1524 for this dispensation.[36] Clement initially resisted the request, but issued in May 1524 a papal brief releasing Charles from the oath and absolving him from all perjuries that might arise from breaking it.[37] The Pope also authorized the Inquisition to suppress oppositions to the upcoming conversions.[37]

On November 25, 1525, Charles issued an edict ordering the expulsion or conversion of remaining Muslims in the Crown of Aragon.[32][38] Similar to the case in Castile, even though the option of exile was available on paper, in practice it was almost impossible.[34][39][40] In order to leave the realm, a Muslim would have had to obtain documentation from Siete Aguas on Aragon's western border, then travel inland across the entire breadth of Castile to embark by sea from A Coruña in the northwest coast.[34] The edict set a deadline of December 31 in the Kingdom of Valencia, and January 26, 1526, in Aragon and Catalonia.[34] Those who failed to arrive on time would be subject to enslavement.[34] A subsequent edict said that those who did not leave by December 8 would need to show proof of baptism.[34][41] Muslims were also ordered to "listen without replying" to Christian teachings.[41]

A very small number of Muslims managed to escape to France and from there to the Muslim North Africa.[41] Some revolted against this order – for example, a revolt broke out in the Serra d'Espadà.[42] The crown's troops defeated this rebellion in a campaign which included the killing of 5,000 Muslims.[42] After the defeat of the rebellions, the entire Crown of Aragon was now nominally converted to Christianity.[43][38] Mosques were demolished, first names and family names were changed, and the religious practice of Islam was driven underground.[44]

Muslim reaction

Crypto-Islam

For those who could not emigrate, conversion was the only option to survive.[45] However, the forcible converts and their descendants (known as the "Moriscos") continued to practice Islam in secret.[45] According to Harvey, "abundant, overwhelming evidence" indicated that most forcible converts were secret Muslims.[46] Historical evidence such as Muslims' writings and Inquisition records corroborated the former's retained religious beliefs.[46][47] Generations of Moriscos were born and died within this religious climate.[48] However, the newly converted were also pressured to conform outwardly to Christianity, such as by attending Mass or consuming food and drink which are forbidden in Islam.[45][49] The situation led to a non-traditional form of Islam in which one's internal intention (niyya), rather than external observation of rituals and laws, was the defining characteristic of one's faith.[48] Hybrid or undefined religious practice featured in many Morisco texts:[50] for example, the works of the Morisco writer Young Man of Arévalo from the 1530s described crypto-Muslims using Christian worship as replacement for regular Islamic rituals.[51] He also wrote about the practice of secret congregational ritual prayer (salat jama'ah),[52] collecting alms in order to perform the pilgrimage to Mecca (although it is unclear whether the journey was ultimately achieved),[52] and the determination and hope among the secret Muslims to reinstitute the full practice of Islam as soon as possible.[53]

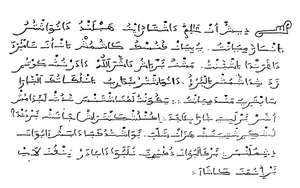

Oran fatwa

The Oran fatwa was a fatwa (an Islamic legal opinion) issued in 1504 to address the crisis of the 1501–1502 forced conversions in Castile.[54] It was issued by North African Maliki scholar Ahmad ibn Abi Jum'ah and set out detailed relaxations of sharia (Islamic law) requirements, allowing Muslims to conform outwardly to Christianity and perform acts that were ordinarily forbidden when necessary to survive.[55] The fatwa included less stringent instructions for the performance of ritual prayers, ritual charity, and ritual ablution; it also told the Muslims how to act when obliged to violate Islamic law, such as by worshiping as Christians, performing blasphemy, or consuming pork and wine.[56] The fatwa enjoyed wide currency among the converted Muslims and their descendants, and one of the surviving Aljamiado translations was dated 1564, 60 years after the original fatwa was issued.[57] Harvey called it "the key theological document" for the study of Spanish Islam following the forced conversions up to the Expulsion of the Moriscos, a description which Islamic studies scholar Devin Stewart repeated.[54][55]

Emigration

The predominant position of Islamic scholars had been that a Muslim could not stay in a country where rulers made proper religious observance impossible:[58] therefore, a Muslim's obligation was to leave when they were able to.[57] Even before the systematic forced conversion, religious leaders had argued that Muslims in Christian territory would be subject to direct and indirect pressure, and preached emigration as a way to protect the religion from eroding.[23] Ahmad al-Wansharis, the contemporary North African scholar and leading authority on Spanish Muslims,[59] wrote in 1491 that emigrating from Christian to Muslim lands was compulsory in almost all circumstances.[23] Further, he urged severe punishment for Muslims who remained and predicted that they would temporarily dwell in hell in the afterlife.[60]

However, the policy of the Christian authorities was generally to block such emigration.[61] Consequently, this option was only practically doable for the wealthiest among those living near the southern coast, and even then with great difficulty.[61] For example, in Sierra Bermeja, Granada in 1501, an option of exile was offered as an alternative to conversion only for those who paid a fee of ten gold doblas, which most citizens could not afford.[62][63] In the same year, villagers of Turre and Teresa near Sierra Cabrera in Almeria fought the Christian militias with help from their North African rescuers at Mojácar while leaving the region.[64] The people of Turre were defeated and the planned escape turned into a massacre; the people of Teresa got away but their properties, except what could fit into their small boats, were left behind and confiscated.[45]

While the edict of conversion in Castile nominally allowed emigration, it explicitly forbade nearly all available destinations for the Muslim population of Castile, and consequently "virtually all" Muslims had to accept conversion.[28] In Aragon, Muslims who wished to leave were required to go to Castile, take an inland route across the breadth of Castile through Madrid and Valladolid, and finally embark by sea on the northwest coast, all on a tight deadline.[34] Religious studies scholar Brian A. Catlos said that emigration "was not a viable option";[39] historian of Spain L. P. Harvey called this prescribed route "insane" and "so difficult to achieve" that the option of exile was "in practice almost nonexistent",[34] and Sephardic historian Maurice Kriegel agreed, saying that "in practical terms it was impossible for them to leave the peninsula".[40] Nevertheless, a small number of Muslims escaped to France, and from there to North Africa.[41]

Armed resistance

The conversion campaign of Cardinal Cisneros in Granada triggered the Rebellion of the Alpujarras (1499–1501).[65][66] The revolt ended in royalist victories, and the defeated rebels were then required to convert.[19][21]

After the edict of conversion in Aragon, Muslims also took up arms, especially in the areas with defensible mountainous terrain.[67] The first armed revolt took place at Benaguasil by Muslims from the town and surrounding areas.[68] An initial royalist assault was repelled, but the town capitulated in March 1526 after a five-week siege, resulting in the rebels' baptism.[69] A more serious rebellion developed in the Sierra de Espadan. The rebel leader called himself "Selim Almanzo", invoking Almanzor, a Muslim leader during the peak of power for Spanish Muslims.[67][70] The Muslims held out for months and pushed back several assaults[71] until the royalist army, enlarged to 7,000 men with a German contingent of 3,000 soldiers, finally made a successful assault on September 19, 1526.[72] The assault ended in the massacring of 5,000 Muslims, including old men and women.[72][67] Survivors of the massacre escaped to the Muela de Cortes; some of them later surrendered and were baptized, while others escaped to North Africa.[73][67]

Sincere conversions

Some converts were sincerely devout in their Christian faith. Cisneros said that some converts chose to die as martyrs when demanded to recant by the Muslim rebels in Granada.[74] A convert named Pedro de Mercado from the village of Ronda refused to join the rebellion in Granada; in response, the rebels burned his house and kidnapped members of his family, including his wife and a daughter.[74] The crown later paid him compensation for his losses.[74]

In 1502, the whole Muslim community of Teruel (part of Aragon bordered with Castile) converted en masse to Christianity, even though the 1502 edict of conversion for Castilian Muslims did not apply to them.[75] Harvey suggested that they were pressured by the Castilians across the border, but historian Trevor Dadson argued that this conversion was unforced, caused instead by centuries of contact with their Christian neighbors and a desire for an equal status with the Christians.[76]

References

Citations

- Harvey 2005, p. 14.

- Carr 2009, p. 40.

- Harvey 1992, p. 9.

- Carr 2009, pp. 40–41.

- Carr 2009, p. 52.

- Harvey 2005, pp. 85–86.

- Carr 2009, p. 81.

- Harvey 1992, p. 325.

- Harvey 2005, pp. 15–16.

- Harvey 2005, pp. 20.

- Harvey 2005, pp. 257.

- Catlos 2014, p. 220.

- Carr 2009, p. 57.

- Harvey 2005, p. 27.

- Carr 2009, p. 58.

- Coleman 2003, p. 6.

- Carr 2009, p. 60.

- Harvey 2005, p. 31.

- Carr 2009, p. 63.

- Harvey 2005, p. 36.

- Harvey 2005, p. 45.

- Harvey 2005, p. 57.

- Harvey 2005, p. 56.

- Edwards 2014, p. 99.

- Edwards 2014, p. 100.

- Harvey 2005, pp. 56–7.

- Harvey 2005, p. 15.

- Harvey 2005, p. 58.

- Harvey 2005, p. 29.

- Harvey 2005, p. 86.

- Harvey 2005, p. 92.

- Harvey 2005, p. 93.

- Lea 1901, p. 71.

- Harvey 2005, p. 94.

- Lea 1901, p. 75.

- Lea 1901, p. 83.

- Lea 1901, p. 84.

- Catlos 2014, p. 226.

- Catlos 2014, p. 227.

- Harvey 2005, p. 99.

- Lea 1901, p. 87.

- Harvey 2005, pp. 99–100.

- Harvey 2005, p. 101.

- Catlos 2014, pp. 226–227.

- Harvey 2005, p. 49.

- Harvey 2006.

- Harvey 2005, p. 102,256.

- Rosa-Rodríguez 2010, p. 153.

- Harvey 2005, p. 52.

- Rosa-Rodríguez 2010, pp. 153–154.

- Harvey 2005, p. 185.

- Harvey 2005, p. 181.

- Harvey 2005, p. 182.

- Harvey 2005, p. 60.

- Stewart 2007, p. 266.

- Harvey 2005, pp. 61–62.

- Harvey 2005, p. 64.

- Harvey 2005, pp. 63–64.

- Stewart 2007, p. 298.

- Hendrickson 2009, p. 25.

- Harvey 2005, p. 48.

- Carr 2009, p. 65.

- Lea 1901, p. 40.

- Harvey 2005, pp. 48–49.

- Lea 1901, p. 33.

- Carr 2009, p. 59.

- Harvey 2005, p. 100.

- Lea 1901, p. 91.

- Lea 1901, pp. 91–92.

- Lea 1901, pp. 92.

- Lea 1901, pp. 93–94.

- Lea 1901, p. 94.

- Lea 1901, p. 95.

- Carr 2009, p. 64.

- Harvey 2005, p. 82.

- Dadson 2006.

Bibliography

- Carr, Matthew (2009). Blood and Faith: The Purging of Muslim Spain. New York: New Press. ISBN 978-1-59558-361-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Catlos, Brian A. (March 20, 2014). Muslims of Medieval Latin Christendom, c.1050–1614. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88939-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Coleman, David (2003). Creating Christian Granada: Society and Religious Culture in an Old-World Frontier City, 1492–1600. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-4111-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dadson, Trevor (February 10, 2006). "Moors of La Mancha". The Times Literary Supplement.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Edwards, John (June 11, 2014). Ferdinand and Isabella. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-89345-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harvey, L. P. (1992). Islamic Spain, 1250 to 1500. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-31962-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harvey, L. P. (May 16, 2005). Muslims in Spain, 1500 to 1614. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-31963-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harvey, L. P. (February 24, 2006). "Fatwas in early modern Spain". The Times Literary Supplement.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hendrickson, Jocelyn N (2009). The Islamic Obligation to Emigrate: Al-Wansharīsī's Asnā al-matājir Reconsidered (PhD). Emory University. Archived from the original on June 18, 2010. Retrieved February 1, 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lea, Henry Charles (1901). The Moriscos of Spain: Their Conversion and Expulsion. Philadelphia: Lea Brothers & Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rosa-Rodríguez, María (2010). "Simulation and Dissimulation: Religious Hybridity in a Morisco Fatwa". Medieval Encounters. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. 16 (2): 143–180. doi:10.1163/138078510X12535199002758. ISSN 1380-7854.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stewart, Devin (2007). "The Identity of "the Muftī of Oran", Abū l-'Abbās Aḥmad b. Abī Jum'ah al-Maghrāwī al-Wahrānī". Al-Qanṭara. Madrid, Spain. 27 (2): 265–301. doi:10.3989/alqantara.2006.v27.i2.2. ISSN 1988-2955.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)