French cruiser Forbin

Forbin was a protected cruiser, the lead ship of the Forbin class, built in the late 1880s for the French Navy. The class was built as part of a construction program intended to provide scouts for the main battle fleet. They were based on the earlier unprotected cruiser Milan, with the addition of an armor deck to improve their usefulness in battle. They had a high top speed for the time, at around 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph), and they carried a main battery of four 138 mm (5.4 in) guns.

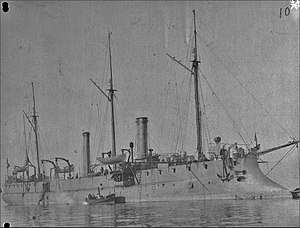

Forbin in Toulon around 1890 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Forbin |

| Builder: | Arsenal de Rochefort |

| Laid down: | May 1886 |

| Launched: | 14 January 1888 |

| Completed: | February 1889 |

| Out of service: | Converted to collier, 1913 |

| Stricken: | 1919 |

| Fate: | Broken up, 1921 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Forbin-class protected cruiser |

| Displacement: | 1,935 long tons (1,966 t) |

| Length: | 95 m (311 ft 8 in) lwl |

| Beam: | 9 m (29 ft 6 in) |

| Draft: | 5.23 m (17 ft 2 in) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 20 to 20.5 knots (37.0 to 38.0 km/h; 23.0 to 23.6 mph) |

| Complement: | 199 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: | Deck: 41 mm (1.6 in) |

Forbin spent the 1890s in the Reserve Squadron, based in the Mediterranean Sea; during this period, she was kept in partial commission to participate in annual training exercises. She was in reserve by 1901, when she had an ammunition fire related to unstable Poudre B propellant charges. Forbin was reactivated in 1906 for service with the Northern Squadron. By 1911, she had been moved to the Moroccan Naval Division. She was converted into a collier in 1913 and was used in that capacity until she was struck from the naval register in 1919. The ship was sold for scrap in 1921.

Design

Beginning in 1879, the French Navy's Conseil des Travaux (Council of Works) had requested designs for small but fast cruisers of about 2,000 long tons (2,032 t) displacement that could be used as scouts for the main battle fleet. The unprotected cruiser Milan was the first of the type, which was developed into the Forbin-type of protected cruisers after the Conseil requested light armor protection for the ships.[1][2] The three Forbins, along with the three very similar Troude-class cruisers, were ordered by Admiral Théophile Aube, then the French Minister of Marine and an ardent supporter of the Jeune École doctrine.[3][4]

Forbin was 95 m (311 ft 8 in) long at the waterline, with a beam of 9 m (29 ft 6 in) and a draft of 5.23 m (17 ft 2 in). She displaced 1,935 long tons (1,966 t). Her crew amounted to 199 officers and enlisted men. The ship's propulsion system consisted of a pair of compound steam engines driving two screw propellers. Steam was provided by six coal-burning fire-tube boilers that were ducted into two funnels. Her machinery was rated to produce 5,800 indicated horsepower (4,300 kW) for a top speed of 20 to 20.5 knots (37.0 to 38.0 km/h; 23.0 to 23.6 mph).[5]

The ship was armed with a main battery of four 138 mm (5.4 in) 30-caliber guns in individual pivot mounts, all in sponsons with two guns per broadside. For close-range defense against torpedo boats, she carried three 47 mm (1.9 in) 3-pounder Hotchkiss guns and four 37 mm (1.5 in) 1-pounder Hotchkiss revolver cannon. She was also armed with four 350 mm (14 in) torpedo tubes in her hull below the waterline, and she had provisions to carry up to 150 naval mines. Armor protection consisted of a curved armor deck that was 41 mm (1.6 in) thick, along with a cofferdam and thin anti-splinter deck covering the machinery spaces.[5]

Service history

The keel for Forbin was laid down at the Arsenal de Rochefort shipyard in Rochefort in May 1886. She was launched on 14 January 1888 and was completed in February 1889, the first member of her class to enter service. She was initially completed with just two of her 138 mm guns, but the other pair were quickly added.[5][6] She completed her sea trials in 1890.[7] By 1893, Forbin had been assigned to the Reserve Squadron, where she spent six months of the year on active service with full crews for maneuvers; the rest of the year was spent laid up with a reduced crew. At that time, the unit also included several older ironclads and the cruisers Tage, Sfax, Davout, and Condor.[8] Forbin took part in the fleet maneuvers in 1894; from 9 to 16 July, the ships involved took on supplies in Toulon for the maneuvers that began later on the 16th. A series of exercises included shooting practice, a blockade simulation, and scouting operations in the western Mediterranean. During the operations, the torpedo boats Audacieux and Mousquetaire collided and Forbin had to take Audacieux under tow back to Toulon. The maneuvers concluded on 3 August.[9]

She was still serving in the unit in 1895, along with Sfax and the unprotected cruiser Milan.[10] She took part in the fleet maneuvers that year, which began on 1 July and concluded on the 27th. She was assigned to "Fleet C", which represented the hostile Italian fleet, which was tasked with defeating "Fleet A" and "Fleet B", which represented the French fleet; the latter two units were individually inferior to "Fleet C", but superior when combined.[11] Forbin remained in the Reserve Squadron in 1897.[12] At some point later in her career, after 1896, Forbin was modernized at Rochefort. She had her mainmast removed, along with all of her torpedo tubes, and she received five more 47 mm guns. Her boilers were replaced with Niclausse-type water-tube boilers and were adapted to incorporate mixed coal and oil firing.[5][13]

By January 1901, Forbin and both of her sister ships had been reduced to the reserve fleet.[14] On 14 April 1901, an accidental propellant fire occurred aboard Forbin, part of a series of fires that resulted from unstable Poudre B charges. The incident occurred at sea steaming from Rochefort to Brest, while the crew was stowing ammunition. Five men were burned in the accident, but the fire did not detonate any adjacent charges and Forbin was only lightly damaged. That night, several men were found to have nearly asphyxiated from the toxic fumes that had been released by the fire.[15][16] The ship was attached to the Reserve Division of the Northern Squadron in 1906, along with three armored cruisers.[17] She took part in the fleet maneuvers that year, which began on 6 July with the concentration of the Northern and Mediterranean Squadrons in Algiers in French Algeria. The maneuvers were conducted in the western Mediterranean, alternating between ports in French North Africa and Toulon and Marseilles, France, and concluding on 4 August.[18] She was present for the 1907 fleet maneuvers, which again saw the Northern and Mediterranean Squadrons unite for large-scale operations held off the coast of French Morocco and in the western Mediterranean. The exercises consisted of two phases and began on 2 July and concluded on 20 July.[19]

The ship remained in service with the Northern Squadron in 1908, by which time it had been reorganized as a cruiser force, consisting of eight armored cruisers and four other protected cruisers.[20] At some point in 1911, Forbin was assigned to the Moroccan Naval Division, where she patrolled French Morocco until 27 September, when she was replaced by the cruiser Lavoisier. Forbin returned to the unit the next year and operated in company with Lavoisier from September, when that vessel returned to the area.[21] Forbin was converted into a collier in 1913.[5] She was struck from the naval register in 1919 and sold to ship breakers two years later.[6]

Notes

- Ropp, pp. 129–130.

- Gardiner, p. 320.

- Ropp, p. 172.

- Gardiner, p. 310.

- Gardiner, p. 309.

- Gardiner & Gray, p. 193.

- Ships: France, p. 601.

- Brassey 1893, p. 70.

- Barry, pp. 208–212.

- Brassey 1895, p. 50.

- Gleig, pp. 195–196.

- Brassey 1897, p. 57.

- France, p. 39.

- Jordan & Caresse, p. 219.

- Jordan & Caresse, p. 234.

- Garbett, pp. 563–564.

- Brassey 1906, p. 39.

- Leyland 1907, pp. 102–106.

- Leyland 1908, pp. 64–68.

- Brassey 1908, p. 49.

- Meirat, p. 22.

References

- Barry, E. B. (1895). "The Naval Manoeuvres of 1894". The United Service: A Monthly Review of Military and Naval Affairs. Philadelphia: L. R. Hamersly & Co. XII: 177–213. OCLC 228667393.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1893). "Chapter IV: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 66–73. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1895). "Chapter III: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 49–59. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1897). "Chapter III: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 56–77. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1906). "Chapter III: Comparative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 38–52. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1908). "Chapter III: Comparative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 48–57. OCLC 496786828.

- Garbett, H., ed. (May 1904). "Naval Notes: France". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. London: J. J. Keliher & Co. XLVIII (315): 560–566. OCLC 1077860366.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- "France". Notes on the Year's Naval Progress. Washington, D.C.: United States Office of Naval Intelligence. XV: 27–41. July 1896. OCLC 727366607.

- Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

- Gleig, Charles (1896). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). "Chapter XII: French Naval Manoeuvres". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 195–207. OCLC 496786828.

- Jordan, John & Caresse, Philippe (2017). French Battleships of World War One. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-639-1.

- Leyland, John (1907). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). "Chapter IV: The French and Italian Manoeuvres". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 102–111. OCLC 496786828.

- Leyland, John (1908). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). "Chapter IV: Foreign Naval Manoeuvres". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 64–82. OCLC 496786828.

- Meirat, Jean (1975). "Details and Operational History of the Third-Class Cruiser Lavoisier". F. P. D. S. Newsletter. Akron: F. P. D. S. III (3): 20–23. OCLC 41554533.

- Ropp, Theodore (1987). Roberts, Stephen S. (ed.). The Development of a Modern Navy: French Naval Policy, 1871–1904. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-141-6.

- "Ships: France". Journal of the American Society of Naval Engineers. III (4): 599–604. 1891. OCLC 1153223376.