Shuanglin Temple

The Shuanglin Temple (Chinese: 双林寺; pinyin: Shuānglín Sì) is a large Buddhist temple in the Shanxi Province of China. It is situated in the countryside of Qiaotou village about 6–7 kilometres (3.7–4.3 mi) southwest of the ancient city of Pingyao. It is among the many cultural monuments located in the Pingyao, which is a UNESCO World Heritage site inscribed in 1997. The temple is protected by the state administration.

| Shuanglin Temple | |

|---|---|

Terracota sculpture of a temple guardian | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Buddhism |

| Province | Shanxi |

| Location | |

| Location | Pingyao |

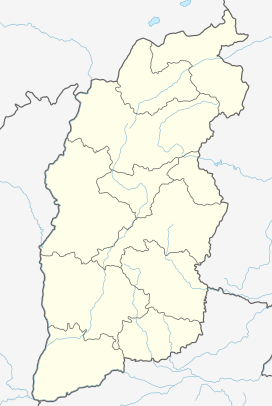

Location of Shuanglin Temple | |

| Geographic coordinates | 37.1708°N 112.125°E |

| Architecture | |

| Completed | 6th century (Qing Dynasty) |

Founded in the 6th century, the temple is notable for its collection of more than 2,000 decorated clay statues that are dated to the 12th-19th centuries.[1] Its original name was Zongdu but it was renamed during the Northern Song Dynasty period as Shuanglin. It is nicknamed the museum of coloured sculptures. Most of them are dated to the period of the Song, Yuan, Ming and Qing dynasties.[2]

History

The Buddhist temple was founded in 571 A.D. during the second year of the Wuping period of the Northern Qi Dynasty. However, the extant buildings date to the Ming and Qing dynasties. It is notable for its collection of over two thousand decorated clay statues dating from the 12th-19th centuries.[3] Shuanglin Temple was refurbished during the cultural revolution of the 20th century under a programme which revived secular culture.[4] It is one of the five sites identified in the city's preservation area of cultural relics which has undergone several renovations.[3] In Pingyao's tortoise-shaped city plan, which is characterized by many coloured art sculptures, the Shuanglin Temple is rated as the city's third treasure.[5]

Geography

The Shuanglin Temple is located some six[6] to seven[7] kilometers away from Pingyao, in Qiatou village's countryside.[3]

Layout

The sculpted figures are displayed in a very systematic manner, in ten halls.[3] The temple complex appears like a fortress as it has a high compound wall with a gate. The ten halls are arranged within three courtyards.[8]

Features

The temple is noted for its colourful sculptures, lifelike in form, which were patterned on the design of the artistic traditions of the Song, Jin and Yuan periods. The themes depicted are generally religious in nature and relate to the daily life of people. They are considered among the finest examples of Chinese coloured sculptures.[3] The number of coloured sculptures are reported to be 2,052, out of which 1,650 are reported to be extant. The height of the sculptures varies between 0.3–3.5 metres (1 ft 0 in–11 ft 6 in). The formats are of bas-relief, high relief and in circular form. There are also wall sculptures and a few are suspended. Buddha, Bodhisattva, Warrior Guards, Arhat, heavenly generals and also common people are the sculptural themes. The background scenes depict towers, buildings, mountains, rivers, clouds, rocks, grasses, flowers, forested trees, and woodlands.[3] The sculptures are displayed behind caged chambers in a tableaux form. There is also statue of husband and wife who took care of this shrine during the Chinese Revolution. The setting of the scene behind the statues is that of flowing water cascades or clouds, and as result the wooden halls appear like grottoes. Maintenance is reported to be poor as many statues are seen in a bad condition for lack of preservation. The temple's external surface is covered with coal dust and looks musty.[8]

Hall of the Devas

Sculptures of Vajrapani and the Four Heavenly Kings are displayed in the Hall of the Devas.[9]

Arhat Hall

Eighteen sculptresses are in the Arhat hall (Luohan Ting; Chinese: 罗汉厅). These are sculpted as noble figures with amicable facial expressions. The garments are similar to the Cao Jiaxiang’s style and have received wide acclaim. The carved garments are tight fitting shirts over loose robes with broad sleeves.[10] The most striking figure among the sculptures in the Arhat hall is that of the holy Guanyin style of sculpting which was popular during the later period of Chinese Buddhism. The gilded sculpted image of Bodhisattva of this period is shown in a cross-legged pose seated on a lotus. A Sumeru throne is sculpted below this image and is fixed over figures of mighty men. The statue is carved in a halo.[9]

Hall of a Thousand Buddhas

The Skanda statue is in the Hall of a Thousand Buddhas, which are considered masterpieces of sculptural art of the Buddhist culture of the Ming dynasty period.[9] The hall has sculpted feminine figurines in a sitting posture. The chief deity is shown with his legs positioned over a coiled dragon.[9]

Bodhisattva Hall

Bodhisattva Hall, called the Pusa Ting (Chinese: 菩萨厅), has a thousand-armed Guanyin. The ceiling in this hall contains depictions of a guard in the form of three-clawed round and bellied figure, and is painted green.[11] The Bodhisattva hall has the sculpture of a young, attractive looking woman said to represent the Bodhisattva, which is sculpted with many hands. The clothing is very rich and ornaments decorate the Bodhisattva. The twenty or more arms of the Bodhisattva are well-sculpted, of very fair skin, with hands set behind the head and on torso.[9]

References

- "Ancient City of Ping Yao". UNESCO Organization. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- Atlas of World Heritage: China. Long River Press. 1 January 2005. pp. 43–. ISBN 978-1-59265-060-6. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- 平遥古城汉英. 五洲传播出版社. 2003. pp. 72–. ISBN 978-7-5085-0250-2.

- Cooper, Eugene; Cooper, Gene (1 February 2013). The Market and Temple Fairs of Rural China: Red Fire. Routledge. pp. 197–. ISBN 978-0-415-52079-9. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- Cai, Yanxin (3 March 2011). Chinese Architecture. Cambridge University Press. pp. 22–. ISBN 978-0-521-18644-5. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- Harper, Damian; Burke, Andrew (1 May 2007). China. Ediz. Inglese. Lonely Planet. pp. 409–. ISBN 978-1-74059-915-3. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- Law, Eugene (2004). 中国指南: Best of China. p. 166. ISBN 9787508504292.

- Leffman, David; Lewis, Simon; Atiyah, Jeremy (1 May 2003). China. Rough Guides. pp. 255–. ISBN 978-1-84353-019-0. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- Falco Howard, Angela (2006). Chinese Sculpture. Yale University Press. pp. 430–. ISBN 978-0-300-10065-5. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- Ye, Lang (1 January 2007). China: Five Thousand Years of History & Civilization. City University of HK Press. pp. 493–. ISBN 978-962-937-140-1. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- Foster, Simon; Lee, Candice; Lin-Liu, Jen; Beth Reiber; Tini Tran; Lee Wing-sze; Christopher D. Winnan (7 March 2012). Frommer's China. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 236–. ISBN 978-1-118-22352-9. Retrieved 7 February 2013.