Fimbria (bacteriology)

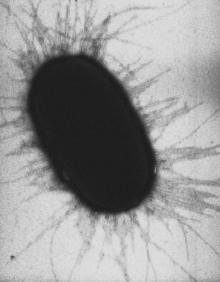

In bacteriology, a fimbria (Latin for 'fringe', plural fimbriae), also referred to as an "attachment pilus" by some scientists, is a type of appendage that is found on many Gram-negative and some Gram-positive bacteria, and that is thinner and shorter than a flagellum. This appendage ranges from 3–10 nanometers in diameter and can be as much as several micrometers long. Fimbriae are used by bacteria to adhere to one another and to adhere to animal cells and some inanimate objects. A bacterium can have as many as 1,000 fimbriae. Fimbriae are only visible with the use of an electron microscope. They may be straight or flexible.

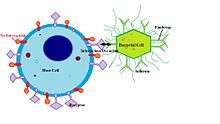

Fimbriae include adhesins which attach them to some sort of substratum so that the bacteria can withstand shear forces and obtain nutrients. For example, E. coli uses them to attach to mannose receptors.

Some aerobic bacteria form a very thin layer at the surface of a broth culture. This layer, termed a pellicle, consists of many aerobic bacteria that adhere to the surface by their fimbriae. Thus, fimbriae allow the aerobic bacteria to remain both on the broth, from which they take nutrients, and near the air.

"Gram-negative bacteria assemble functional amyloid surface fibers termed curli."[1] Curli are a type of fimbriae;[2] another type are called type I fimbriae.[2] Curli are composed of proteins called curlins.[1] Some of the genes involved are CsgA, CsgB, CsgC, CsgD, CsgE, CsgF, and CsgG.[1]

Virulence

Fimbriae are one of the primary mechanisms of virulence for E. coli, Bordetella pertussis, Staphylococcus and Streptococcus bacteria. Their presence greatly enhances the bacteria's ability to attach to the host and cause disease.[4]

See also

References

- Epstein, EA; Reizian, MA; Chapman, MR (2009), "Spatial clustering of the curlin secretion lipoprotein requires curli fiber assembly.", J Bacteriol, 191 (2): 608–615, doi:10.1128/JB.01244-08, PMC 2620823, PMID 19011034.

- Cookson, AL; Cooley, WA; Woodward, MJ (2002), "The role of type 1 and curli fimbriae of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in adherence to abiotic surfaces", Int J Med Microbiol, 292 (3–4): 195–205, doi:10.1078/1438-4221-00203, PMID 12398210.

- WI, Kenneth Todar, Madison. "Colonization and Invasion by Bacterial Pathogens". www.textbookofbacteriology.net. Retrieved 2016-12-03.

- Connell I, Agace W, Klemm P, Schembri M, Mărild S, Svanborg C (September 1996). "Type 1 fimbrial expression enhances Escherichia coli virulence for the urinary tract". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93 (18): 9827–32. Bibcode:1996PNAS...93.9827C. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.18.9827. PMC 38514. PMID 8790416.

External links

- Fimbriae+Proteins at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)