Fibromyalgia

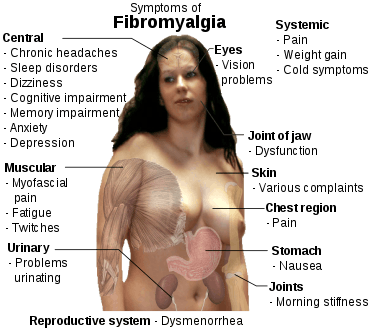

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a medical condition characterized by chronic widespread pain and a heightened pain response to pressure.[3] Other symptoms include tiredness to a degree that normal activities are affected, sleep problems and troubles with memory.[4] Some people also report restless legs syndrome, bowel or bladder problems, numbness and tingling and sensitivity to noise, lights or temperature.[5] Fibromyalgia is frequently associated with depression, anxiety and posttraumatic stress disorder.[4] Other types of chronic pain are also frequently present.[4]

| Fibromyalgia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) |

| |

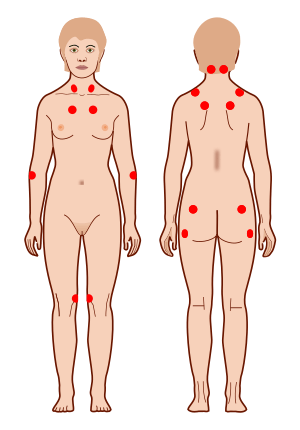

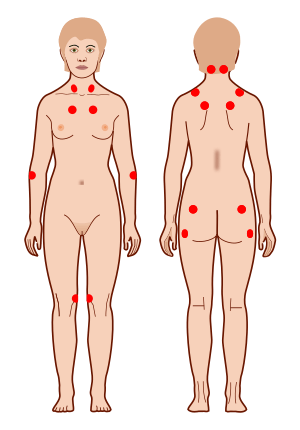

| The location of the nine paired tender points that constitute the 1990 American College of Rheumatology criteria for fibromyalgia | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Psychiatry, rheumatology, neurology[2] |

| Symptoms | Widespread pain, feeling tired, sleep problems[3][4] |

| Usual onset | Middle age[5] |

| Duration | Long term[3] |

| Causes | Unknown[4][5] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms after ruling out other potential causes[4][5] |

| Differential diagnosis | Polymyalgia rheumatica, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, thyroid disease[6] |

| Treatment | Sufficient sleep and exercise, healthy diet[5] |

| Medication | Duloxetine, milnacipran, pregabalin, gabapentin[5][7] |

| Prognosis | Normal life expectancy[5] |

| Frequency | 2–8%[4] |

The cause of fibromyalgia is unknown, however, it is believed to involve a combination of genetic and environmental factors.[4][5] The condition runs in families and many genes are believed to be involved.[8] Environmental factors may include psychological stress, trauma and certain infections.[4] The pain appears to result from processes in the central nervous system and the condition is referred to as a "central sensitization syndrome".[3][4] Fibromyalgia is recognized as a disorder by the US National Institutes of Health and the American College of Rheumatology.[5][9] There is no specific diagnostic test.[5] Diagnosis involves first ruling out other potential causes and verifying that a set number of symptoms are present.[4][5]

The treatment of fibromyalgia can be difficult.[5] Recommendations often include getting enough sleep, exercising regularly, and eating a healthy diet.[5] Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) may also be helpful.[4] The medications duloxetine, milnacipran or pregabalin may be used.[5] Use of opioid pain medication is controversial, with some stating their usefulness is poorly supported by evidence[5][10] and others saying that weak opioids may be reasonable if other medications are not effective.[11] Dietary supplements lack evidence to support their use.[5] While fibromyalgia can last a long time, it does not result in death or tissue damage.[5]

Fibromyalgia is estimated to affect 2–8% of the population.[4] Women are affected about twice as often as men.[4] Rates appear similar in different areas of the world and among different cultures.[4] Fibromyalgia was first defined in 1990, with updated criteria in 2011.[4] There is controversy about the classification, diagnosis and treatment of fibromyalgia.[12][13] While some feel the diagnosis of fibromyalgia may negatively affect a person, other research finds it to be beneficial.[4] The term "fibromyalgia" is from New Latin fibro-, meaning "fibrous tissues", Greek μυώ myo-, "muscle", and Greek άλγος algos, "pain"; thus, the term literally means "muscle and fibrous connective tissue pain".[14]

Classification

Fibromyalgia is classed as a disorder of pain processing due to abnormalities in how pain signals are processed in the central nervous system.[15] The American College of Rheumatology classifies fibromyalgia as being a functional somatic syndrome.[12] The expert committee of the European League Against Rheumatism classifies fibromyalgia as a neurobiological disorder and as a result, exclusively give pharmacotherapy their highest level of support.[12] The International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) lists fibromyalgia as a diagnosable disease under "Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue," under the code M79-7, and states that fibromyalgia syndrome should be classified as a functional somatic syndrome rather than a mental disorder. Although mental disorders and some physical disorders are commonly co-morbid with fibromyalgia – especially anxiety, depression, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic fatigue syndrome – the ICD states that these should be diagnosed separately.[12]

Differences in psychological and autonomic nervous system profiles among affected individuals may indicate the existence of fibromyalgia subtypes. A 2007 review divides individuals with fibromyalgia into four groups as well as "mixed types":[16]

- "extreme sensitivity to pain but no associated psychiatric conditions" (may respond to medications that block the 5-HT3 receptor)

- "fibromyalgia and comorbid, pain-related depression" (may respond to antidepressants)

- "depression with concomitant fibromyalgia syndrome" (may respond to antidepressants)

- "fibromyalgia due to somatization" (may respond to psychotherapy)

Signs and symptoms

The defining symptoms of fibromyalgia are chronic widespread pain, fatigue, sleep disturbance, and heightened pain in response to tactile pressure (allodynia).[17] Other symptoms may include tingling of the skin (paresthesias),[17] prolonged muscle spasms, weakness in the limbs, nerve pain, muscle twitching, palpitations,[18] and functional bowel disturbances.[19][20]

Many people experience cognitive problems[17][21] (known as "fibrofog"), which may be characterized by impaired concentration,[22] problems with short-[22][23] and long-term memory, short-term memory consolidation,[23] impaired speed of performance,[22][23] inability to multi-task, cognitive overload,[22][23] and diminished attention span. Fibromyalgia is often associated with anxiety and depressive symptoms.[23]

Other symptoms often attributed to fibromyalgia that may be due to a comorbid disorder include myofascial pain syndrome, also referred to as chronic myofascial pain, diffuse non-dermatomal paresthesias, functional bowel disturbances and irritable bowel syndrome, genitourinary symptoms and interstitial cystitis, dermatological disorders, headaches, myoclonic twitches, and symptomatic low blood sugar. Although fibromyalgia is classified based on the presence of chronic widespread pain, pain may also be localized in areas such as the shoulders, neck, low back, hips, or other areas. Many sufferers also experience varying degrees of myofascial pain and have high rates of comorbid temporomandibular joint dysfunction. 20–30% of people with rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus may also have fibromyalgia.[24]

Cause

The cause of fibromyalgia is unknown. However, several hypotheses have been developed including "central sensitization".[17] This theory proposes that people with fibromyalgia have a lower threshold for pain because of increased reactivity of pain-sensitive nerve cells in the spinal cord or brain.[3] Neuropathic pain and major depressive disorder often co-occur with fibromyalgia – the reason for this comorbidity appears to be due to shared genetic abnormalities, which leads to impairments in monoaminergic, glutamatergic, neurotrophic, opioid and proinflammatory cytokine signaling. In these vulnerable individuals, psychological stress or illness can cause abnormalities in inflammatory and stress pathways that regulate mood and pain. Eventually, a sensitization and kindling effect occur in certain neurons leading to the establishment of fibromyalgia and sometimes a mood disorder.[25] The evidence suggests that the pain in fibromyalgia results primarily from pain-processing pathways functioning abnormally. In simple terms, it can be described as the volume of the neurons being set too high and this hyper-excitability of pain-processing pathways and under-activity of inhibitory pain pathways in the brain results in the affected individual experiencing pain. Some neurochemical abnormalities that occur in fibromyalgia also regulate mood, sleep, and energy, thus explaining why mood, sleep, and fatigue problems are commonly co-morbid with fibromyalgia.[15]

Genetics

A mode of inheritance is currently unknown, but it is most probably polygenic.[8] Research has also demonstrated that fibromyalgia is potentially associated with polymorphisms of genes in the serotoninergic,[26] dopaminergic[27] and catecholaminergic systems.[28] However, these polymorphisms are not specific for fibromyalgia and are associated with a variety of allied disorders (e.g. chronic fatigue syndrome,[29] irritable bowel syndrome[30]) and with depression.[31] Individuals with the 5-HT2A receptor 102T/C polymorphism have been found to be at increased risk of developing fibromyalgia.[32]

Lifestyle and trauma

Stress may be an important precipitating factor in the development of fibromyalgia.[33] Fibromyalgia is frequently comorbid with stress-related disorders such as chronic fatigue syndrome, posttraumatic stress disorder, irritable bowel syndrome and depression.[34] A systematic review found significant association between fibromyalgia and physical and sexual abuse in both childhood and adulthood, although the quality of studies was poor.[35] Poor lifestyles including being a smoker, obesity and lack of physical activity may increase the risk of an individual developing fibromyalgia.[36] A meta analysis found psychological trauma to be associated with FM, although not as strongly as in chronic fatigue syndrome.[37]

Some authors have proposed that, because exposure to stressful conditions can alter the function of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the development of fibromyalgia may stem from stress-induced disruption of the HPA axis.[38]

Sleep disturbances

Poor sleep is a risk factor for fibromyalgia.[39] In 1975, Moldofsky and colleagues reported the presence of anomalous alpha wave activity (typically associated with arousal states) measured by electroencephalogram (EEG) during non-rapid eye movement sleep of "fibrositis syndrome".[20] By disrupting stage IV sleep consistently in young, healthy subjects, the researchers reproduced a significant increase in muscle tenderness similar to that experienced in "neurasthenic musculoskeletal pain syndrome" but which resolved when the subjects were able to resume their normal sleep patterns.[40] Mork and Nielsen used prospective data and identified a dose-dependent association between sleep problems and risk of FM.[41]

Psychological factors

There is strong evidence that major depression is associated with fibromyalgia as with other chronic pain conditions (1999),[42] although the direction of the causal relationship is unclear.[43] A comprehensive review into the relationship between fibromyalgia and major depressive disorder (MDD) found substantial similarities in neuroendocrine abnormalities, psychological characteristics, physical symptoms and treatments between fibromyalgia and MDD, but currently available findings do not support the assumption that MDD and fibromyalgia refer to the same underlying construct or can be seen as subsidiaries of one disease concept.[44] Indeed, the sensation of pain has at least two dimensions: a sensory dimension which processes the magnitude and location of the pain, and an affective-motivational dimension which processes the unpleasantness. Accordingly, a study that employed functional magnetic resonance imaging to evaluate brain responses to experimental pain among people with fibromyalgia found that depressive symptoms were associated with the magnitude of clinically induced pain response specifically in areas of the brain that participate in affective pain processing, but not in areas involved in sensory processing which indicates that the amplification of the sensory dimension of pain in fibromyalgia occurs independently of mood or emotional processes.[45] Fibromyalgia has also been linked with bipolar disorder, particularly the hypomania component.[46]

Non-celiac gluten sensitivity

Non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) may be an underlying cause of fibromyalgia symptoms but further research is needed.[47][48]

Pathophysiology

Pain processing abnormalities

Abnormalities in the ascending and descending pathways involved in processing pain have been observed in fibromyalgia. Fifty percent less stimulus is needed to evoke pain in those with fibromyalgia.[49] A proposed mechanism for chronic pain is sensitization of secondary pain neurons mediated by increased release of proinflammatory cytokines and nitric oxide by glial cells.[50] Inconsistent reports of decreased serum and CSF values of serotonin have been observed. There is also some data that suggests altered dopaminergic and noradrenergic signaling in fibromyalgia.[51] Supporting the monoamine related theories is the efficacy of monoaminergic antidepressants in fibromyalgia.[52][53]

Neuroendocrine system

Studies on the neuroendocrine system and HPA axis in fibromyalgia have been inconsistent. One study found fibromyalgia patients exhibited higher plasma cortisol, more extreme peaks and troughs, and higher rates of dexamethasone non suppression. However, other studies have only found correlations between a higher cortisol awakening response and pain, and not any other abnormalities in cortisol.[49] Increased baseline ACTH and increase in response to stress have been observed, hypothesized to be a result of decreased negative feedback.[51]

Autonomic nervous system

Autonomic nervous system abnormalities have been observed in fibromyalgia, including decreased vasoconstriction response, increased drop in blood pressure and worsening of symptoms in response to tilt table test, and decreased heart rate variability. Heart rate variabilities observed were different in males and females.[49]

Sleep

Disrupted sleep, insomnia, and poor-quality sleep occur frequently in FM, and may contribute to pain by decreased release of IGF-1 and human growth hormone, leading to decreased tissue repair. Restorative sleep was correlated with improvement in pain related symptoms.[49]

Neuroimaging

Neuroimaging studies have observed decreased levels of N-acetylaspartic acid (NAA) in the hippocampus of people with fibromyalgia, indicating decreased neuron functionality in this region. Altered connectivity and decreased grey matter of the default mode network,[54] the insula, and executive attention network have been found in fibromyalgia. Increased levels of glutamate and glutamine have been observed in the amygdala, parts of the prefrontal cortex, the posterior cingulate cortex, and the insula, correlating with pain levels in FM. Decreased GABA has been observed in the anterior insular in fibromyalgia. However, neuroimaging studies, in particular neurochemical imaging studies, are limited by methodology and interpretation.[55] Increased cerebral blood flow in response to pain was found in one fMRI study.[50] Findings of decreased blood flow in the thalamus and other regions of the basal ganglia correlating with treatment have been relatively consistent over three studies. Decreased binding of μ-opioid receptor have been observed; however, it is unknown if this is a result of increased endogenous binding in response to pain, or down regulation.[51]

Immune system

Overlaps have been drawn between chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia. One study found increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in fibromyalgia, which may increase sensitivity to pain, and contribute to mood problems.[56] Increased levels of IL-1RA, Interleukin 6 and Interleukin 8 have been found.[57] Neurogenic inflammation has been proposed as a contributing factor to fibromyalgia.[58] A systematic review found most cytokines levels were similar in patients and controls, except for IL-1 receptor antagonist, IL-6 and IL-8.[59]

Diagnosis

There is no single test that can fully diagnose fibromyalgia and there is debate over what should be considered essential diagnostic criteria and whether an objective diagnosis is possible. In most cases, people with fibromyalgia symptoms may also have laboratory test results that appear normal and many of their symptoms may mimic those of other rheumatic conditions such as arthritis or osteoporosis. The most widely accepted set of classification criteria for research purposes was elaborated in 1990 by the Multicenter Criteria Committee of the American College of Rheumatology. These criteria, which are known informally as "the ACR 1990", define fibromyalgia according to the presence of the following criteria:

- A history of widespread pain lasting more than three months – affecting all four quadrants of the body, i.e., both sides, and above and below the waist.

- Tender points – there are 18 designated possible tender points (although a person with the disorder may feel pain in other areas as well). Diagnosis is no longer based on the number of tender points.[60][61]

The ACR criteria for the classification of patients were originally established as inclusion criteria for research purposes and were not intended for clinical diagnosis but have now become the de facto diagnostic criteria in the clinical setting. The number of tender points that may be active at any one time may vary with time and circumstance. A controversial study was done by a legal team looking to prove their client's disability based primarily on tender points and their widespread presence in non-litigious communities prompted the lead author of the ACR criteria to question now the useful validity of tender points in diagnosis.[62] Use of control points has been used to cast doubt on whether a person has fibromyalgia, and to claim the person is malingering; however, no research has been done for the use of control points to diagnose fibromyalgia, and such diagnostic tests have been advised against, and people complaining of pain all over should still have fibromyalgia considered as a diagnosis.[12]

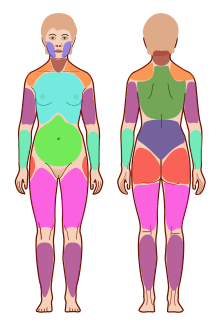

2010 provisional criteria

In 2010, the American College of Rheumatology approved provisional revised diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia that eliminated the 1990 criteria's reliance on tender point testing.[63] The revised criteria use a widespread pain index (WPI) and symptom severity scale (SS) in place of tender point testing under the 1990 criteria. The WPI counts up to 19 general body areas[lower-alpha 1] in which the person has experienced pain in the preceding two weeks. The SS rates the severity of the person's fatigue, unrefreshed waking, cognitive symptoms, and general somatic symptoms,[lower-alpha 2] each on a scale from 0 to 3, for a composite score ranging from 0 to 12. The revised criteria for diagnosis are:

- WPI ≥ 7 and SS ≥ 5 OR WPI 3–6 and SS ≥ 9,

- Symptoms have been present at a similar level for at least three months, and

- No other diagnosable disorder otherwise explains the pain.[63]:607

Multidimensional assessment

Some research has suggested not to categorise fibromyalgia as a somatic disease or a mental disorder, but to use a multidimensional approach taking into consideration somatic symptoms, psychological factors, psychosocial stressors and subjective belief regarding fibromyalgia.[64] A review has looked at self-report questionnaires assessing fibromyalgia on multiple dimensions, including:[64]

- Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire[65]

- Widespread Pain Index[66]

- Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- Multiple Ability Self-Report Questionnaire[67]

- Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory

- Medical Outcomes Study Sleep Scale

Differential diagnosis

As many as two out of every three people who are told that they have fibromyalgia by a rheumatologist may have some other medical condition instead.[68] Certain systemic, inflammatory, endocrine, rheumatic, infectious, and neurologic disorders may cause fibromyalgia-like symptoms, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren syndrome, non-celiac gluten sensitivity, hypothyroidism, ankylosing spondylitis, polymyalgia rheumatica, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic-related polyenthesitis, hepatitis C, peripheral neuropathies, a nerve compression syndrome (such as carpal tunnel syndrome), multiple sclerosis and myasthenia gravis. The differential diagnosis is made during the evaluation on the basis of the person's medical history, physical examination, and laboratory investigations.[47][68][69][70]

Management

As with many other medically unexplained syndromes, there is no universally accepted treatment or cure for fibromyalgia, and treatment typically consists of symptom management. Developments in the understanding of the pathophysiology of the disorder have led to improvements in treatment, which include prescription medication, behavioral intervention, and exercise. Indeed, integrated treatment plans that incorporate medication, patient education, aerobic exercise, and cognitive behavioral therapy have been shown to be effective in alleviating pain and other fibromyalgia-related symptoms.[71]

The Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany,[72] the European League Against Rheumatism[73] and the Canadian Pain Society[74] currently publish guidelines for the diagnosis and management of FMS.

Medications

Health Canada and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have approved pregabalin[75] and duloxetine for the management of fibromyalgia. The FDA also approved milnacipran, but the European Medicines Agency refused marketing authority.[76]

Antidepressants

Antidepressants are "associated with improvements in pain, depression, fatigue, sleep disturbances, and health-related quality of life in people with FMS."[77] The goal of antidepressants should be symptom reduction and if used long term, their effects should be evaluated against side effects. A small number of people benefit significantly from the SNRIs duloxetine and milnacipran and the tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), such as amitriptyline. However, many people experience more adverse effects than benefits.[78][79] While amitriptyline has been used as a first line treatment, the quality of evidence to support this use is poor.[80]

It can take up to three months to derive benefit from the antidepressant amitriptyline and between three and six months to gain the maximal response from duloxetine, milnacipran, and pregabalin. Some medications have the potential to cause withdrawal symptoms when stopping so gradual discontinuation may be warranted particularly for antidepressants and pregabalin.[12]

There is tentative evidence that the benefits and harms of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) appear to be similar.[81] SSRIs may be used to treat depression in people diagnosed with fibromyalgia.[82]

Tentative evidence suggests that monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) such as pirlindole and moclobemide are moderately effective for reducing pain.[83] Very low-quality evidence suggests pirlindole as more effective at treating pain than moclobemide.[83] Side effects of MAOIs may include nausea and vomiting.[83]

Anti-seizure medication

The anti-convulsant medications gabapentin and pregabalin may be used to reduce pain.[7][84] There is tentative evidence that gabapentin may be of benefit for pain in about 18% of people with fibromyalgia.[7] It is not possible to predict who will benefit, and a short trial may be recommended to test the effectiveness of this type of medication. Approximately 6/10 people who take gabapentin to treat pain related to fibromyalgia experience unpleasant side effects such as dizziness, abnormal walking, or swelling from fluid accumulation.[85] Pregabalin demonstrates a benefit in about 9% of people.[86] Pregabalin reduced time off work by 0.2 days per week.[87]

Opioids

The use of opioids is controversial. As of 2015, no opioid is approved for use in this condition by the FDA.[88] The National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) in 2014 stated that there was a lack of evidence for opioids for most people.[5] The Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany in 2012 made no recommendation either for or against the use of weak opioids because of the limited amount of scientific research addressing their use in the treatment of FM. They strongly advise against using strong opioids.[72] The Canadian Pain Society in 2012 said that opioids, starting with a weak opioid like tramadol, can be tried but only for people with moderate to severe pain that is not well-controlled by non-opioid painkillers. They discourage the use of strong opioids and only recommend using them while they continue to provide improved pain and functioning. Healthcare providers should monitor people on opioids for ongoing effectiveness, side effects and possible unwanted drug behaviors.[74]

The European League Against Rheumatism in 2008 recommends tramadol and other weak opioids may be used for pain but not strong opioids.[73] A 2015 review found fair evidence to support tramadol use if other medications do not work.[88] A 2018 review found little evidence to support the combination of paracetamol (acetaminophen) and tramadol over a single medication.[89] Goldenberg et al suggest that tramadol works via its serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibition, rather than via its action as a weak opioid receptor agonist.[10]

A large study of US people with fibromyalgia found that between 2005 and 2007 37.4% were prescribed short-acting opioids and 8.3% were prescribed long-acting opioids,[90] with around 10% of those prescribed short-acting opioids using tramadol;[91] and a 2011 Canadian study of 457 people with FM found 32% used opioids and two thirds of those used strong opioids.[74]

Others

A 2007 review concluded that a period of nine months of growth hormone was required to reduce fibromyalgia symptoms and normalize IGF-1.[92] A 2014 study also found some evidence supporting its use.[93] Sodium oxybate increases growth hormone production levels through increased slow-wave sleep patterns. However, this medication was not approved by the FDA for the indication for use in people with fibromyalgia due to the concern for abuse.[94]

The muscle relaxants cyclobenzaprine, carisoprodol with acetaminophen and caffeine and tizanidine are sometimes used to treat fibromyalgia; however as of 2015 they are not approved for this use in the United States.[95][96] The use of NSAIDs is not recommended as first line therapy.[97] Moreover, NSAIDs cannot be considered as useful in the management of fibromyalgia.[98]

Dopamine agonists (e.g. pramipexole and ropinirole) resulted in some improvement in a minority of people,[99] but side effects, including the onset of impulse control disorders like compulsive gambling and shopping, might be a concern for some people.[100]

There is some evidence that 5HT3 antagonists may be beneficial.[101] Preliminary clinical data finds that low-dose naltrexone (LDN) may provide symptomatic improvement.[102]

Very low-quality evidence suggests quetiapine may be effective in fibromyalgia.[103]

No high-quality evidence exists that suggests synthetic THC (nabilone) helps with fibromyalgia.[104]

Intravenous Iloprost may be effective in reducing frequency and severity of attacks for people with fibromyalgia secondary to scleroderma.[105]

A small double-blinded, placebo-controlled proof-of-concept trial found Famciclovir and celecoxib may be effective in reducing fibromyalgia related pain.[106] These medications' mechanisms are thought to suppress latent herpes virus infection which some fibromyalgia patients are theorized to suffer from.[106]

Therapy

Due to the uncertainty about the pathogenesis of FM, current treatment approaches focus on management of symptoms to improve quality of life,[107] using integrated pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches.[108] There is no single intervention shown to be effective for all patients [109] and no gold treatment standard exists for FM.[110] Multimodal/multidisciplinary therapy is recommended to target multiple underlying factors of FM.[111] A meta-analysis of 1,119 subjects found "strong evidence that multicomponent treatment has beneficial short-term effects on key symptoms of FMS." [112] There is weak evidence to support the use of multidisciplinary rehabilitation programs.[113]

Cognitive behavioural therapy

Non-pharmacological components include cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), exercise and psychoeducation (specifically, sleep hygiene).[114][115][116][117] CBT and related psychological and behavioural therapies have a small to moderate effect in reducing symptoms of fibromyalgia.[118][115] Effect sizes tend to be small when CBT is used as a stand-alone treatment for FM patients, but these improve significantly when CBT is part of a wider multidisciplinary treatment program.[119] The greatest benefit occurs when CBT is used along with exercise.[71][120]

A 2010 systematic review of 14 studies reported that CBT improves self-efficacy or coping with pain and reduces the number of physician visits at post-treatment, but has no significant effect on pain, fatigue, sleep or health-related quality of life at post-treatment or follow-up. Depressed mood was also improved but this could not be distinguished from some risks of bias.[121]

Mind-body therapy

Mind-body therapies focus on interactions among the brain, mind, body and behaviour. The National Centre for Complementary and Alternative Medicine defines the treatments under holistic principle that mind-body are interconnected and through treatment there is improvement in psychological and physical well-being, and allow patient to have an active role in their treatment.[122] There are several therapies such as mindfulness, movement therapy (yoga, tai chi), psychological (including CBT) and biofeedback (use of technology to give audio/visual feedback on physiological processes like heart rate). There is only weak evidence that psychological intervention is effective in the treatment of fibromyalgia and no good evidence for the benefit of other mind-body therapies.[122]

Exercise

There is strong evidence indicating that exercise improves fitness and sleep and may reduce pain and fatigue in some people with fibromyalgia.[123][124] In particular, there is strong evidence that cardiovascular exercise is effective for some people.[125] Low-quality evidence suggests that high-intensity resistance training may improve pain and strength in women.[126] Studies of different forms of aerobic exercise for adults with fibromyalgia indicate that aerobic exercise improves quality of life, decreases pain, slightly improves physical function and makes no difference in fatigue and stiffness.[127] Long-term effects are uncertain.[127] Combinations of different exercises such as flexibility and aerobic training may improve stiffness.[128] However, the evidence is of low-quality.[128] Tentative evidence suggests aquatic training can improve symptoms and wellness but, further research is required.[129]

A recommended approach to a graded exercise program begins with small, frequent exercise periods and builds up from there.[130] In children, fibromyalgia is often treated with an intense physical and occupational therapy program for musculoskeletal pain syndromes. These programs also employ counseling, art therapy, and music therapy. These programs are evidence-based and report long-term total pain resolution rates as high as 88%.[131] Limited evidence suggests vibration training in combination with exercise may improve pain, fatigue and stiffness.[132]

Prognosis

Although in itself neither degenerative nor fatal, the chronic pain of fibromyalgia is pervasive and persistent. Most people with fibromyalgia report that their symptoms do not improve over time. An evaluation of 332 consecutive new people with fibromyalgia found that disease-related factors such as pain and psychological factors such as work status, helplessness, education, and coping ability had an independent and significant relationship to FM symptom severity and function.[133]

Epidemiology

Fibromyalgia is estimated to affect 2–8% of the population.[4][134] Females are affected about twice as often as males based on criteria as of 2014.[4]

Fibromyalgia may not be diagnosed in up to 75% of affected people.[15]

History

Chronic widespread pain had already been described in the literature in the 19th century but the term fibromyalgia was not used until 1976 when Dr P.K. Hench used it to describe these symptoms.[12] Many names, including "muscular rheumatism", "fibrositis", "psychogenic rheumatism", and "neurasthenia" were applied historically to symptoms resembling those of fibromyalgia.[135] The term fibromyalgia was coined by researcher Mohammed Yunus as a synonym for fibrositis and was first used in a scientific publication in 1981.[136] Fibromyalgia is from the Latin fibra (fiber)[137] and the Greek words myo (muscle)[138] and algos (pain).[139]

Historical perspectives on the development of the fibromyalgia concept note the "central importance" of a 1977 paper by Smythe and Moldofsky on fibrositis.[140][141] The first clinical, controlled study of the characteristics of fibromyalgia syndrome was published in 1981,[142] providing support for symptom associations. In 1984, an interconnection between fibromyalgia syndrome and other similar conditions was proposed,[143] and in 1986, trials of the first proposed medications for fibromyalgia were published.[143]

A 1987 article in the Journal of the American Medical Association used the term "fibromyalgia syndrome" while saying it was a "controversial condition".[144] The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) published its first classification criteria for fibromyalgia in 1990,[145] although these are not strictly diagnostic criteria.[16]

Society and culture

Economics

People with fibromyalgia generally have higher health-care costs and utilization rates. A study of almost 20,000 Humana members enrolled in Medicare Advantage and commercial plans compared costs and medical utilizations and found that people with fibromyalgia used twice as much pain-related medication as those without fibromyalgia. Furthermore, the use of medications and medical necessities increased markedly across many measures once diagnosis was made.[146]

Controversies

Fibromyalgia was defined relatively recently. It continues to be a disputed diagnosis. Dr. Frederick Wolfe, lead author of the 1990 paper that first defined the diagnostic guidelines for fibromyalgia, stated in 2008 that he believed it "clearly" not to be a disease but instead a physical response to depression and stress.[147] In 2013 Wolfe added that its causes "are controversial in a sense" and "there are many factors that produce these symptoms – some are psychological and some are physical and it does exist on a continuum".[148]

Some members of the medical community do not consider fibromyalgia a disease because of a lack of abnormalities on physical examination and the absence of objective diagnostic tests.[140][149]

Neurologists and pain specialists tend to view fibromyalgia as a pathology due to dysfunction of muscles and connective tissue as well as functional abnormalities in the central nervous system. Rheumatologists define the syndrome in the context of "central sensitization" – heightened brain response to normal stimuli in the absence of disorders of the muscles, joints, or connective tissues. On the other hand, psychiatrists often view fibromyalgia as a type of affective disorder, whereas specialists in psychosomatic medicine tend to view fibromyalgia as being a somatic symptom disorder. These controversies do not engage healthcare specialists alone; some patients object to fibromyalgia being described in purely somatic terms. There is extensive research evidence to support the view that the central symptom of fibromyalgia, namely pain, has a neurogenic origin, though this is consistent in both views.[12][15]

The validity of fibromyalgia as a unique clinical entity is a matter of contention because "no discrete boundary separates syndromes such as FMS, chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, or chronic muscular headaches".[125][150] Because of this symptomatic overlap, some researchers have proposed that fibromyalgia and other analogous syndromes be classified together as functional somatic syndromes for some purposes.[151]

Research

Investigational medications include cannabinoids and the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist tropisetron.[152] Low-quality evidence found an improvement in symptoms with a gluten free diet among those without celiac disease.[153] A controlled study of guaifenesin failed to demonstrate any benefits from this treatment.[154][155]

A small 2018 study found some neuroinflammation in people with fibromyalgia.[156]

Notes

- Shoulder girdle (left & right), upper arm (left & right), lower arm (left & right), hip/buttock/trochanter (left & right), upper leg (left & right), lower leg (left & right), jaw (left & right), chest, abdomen, back (upper & lower), and neck.[63]:607

- Somatic symptoms include, but are not limited to: muscle pain, irritable bowel syndrome, fatigue or tiredness, problems thinking or remembering, muscle weakness, headache, pain or cramps in the abdomen, numbness or tingling, dizziness, insomnia, depression, constipation, pain in the upper abdomen, nausea, nervousness, chest pain, blurred vision, fever, diarrhea, dry mouth, itching, wheezing, Raynaud's phenomenon, hives or welts, ringing in the ears, vomiting, heartburn, oral ulcers, loss of or changes in taste, seizures, dry eyes, shortness of breath, loss of appetite, rash, sun sensitivity, hearing difficulties, easy bruising, hair loss, frequent or painful urination, and bladder spasms.[63]:607

References

- "fibromyalgia". Collins Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 4 October 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- "Neurology Now: Fibromyalgia: Is Fibromyalgia Real? | American Academy of Neurology". tools.aan.com. October 2009. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- Ngian GS, Guymer EK, Littlejohn GO (February 2011). "The use of opioids in fibromyalgia". Int J Rheum Dis. 14 (1): 6–11. doi:10.1111/j.1756-185X.2010.01567.x. PMID 21303476.

- Clauw, Daniel J. (16 April 2014). "Fibromyalgia". JAMA. 311 (15): 1547–55. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.3266. PMID 24737367. S2CID 43693607.

- "Questions and Answers about Fibromyalgia". NIAMS. July 2014. Archived from the original on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- Ferri, Fred F. (2010). Ferri's differential diagnosis : a practical guide to the differential diagnosis of symptoms, signs, and clinical disorders (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Mosby. p. Chapter F. ISBN 978-0323076999.

- Cooper, TE; Derry, S; Wiffen, PJ; Moore, RA (3 January 2017). "Gabapentin for fibromyalgia pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1: CD012188. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012188.pub2. PMC 6465053. PMID 28045473.

- Buskila D, Sarzi-Puttini P (2006). "Biology and therapy of fibromyalgia. Genetic aspects of fibromyalgia syndrome". Arthritis Research & Therapy. 8 (5): 218. doi:10.1186/ar2005. PMC 1779444. PMID 16887010.

- "Fibromyalgia". American College of Rheumatology. May 2015. Archived from the original on 17 March 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- Goldenberg, DL; Clauw, DJ; Palmer, RE; Clair, AG (May 2016). "Opioid Use in Fibromyalgia: A Cautionary Tale". Mayo Clinic Proceedings (Review). 91 (5): 640–8. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.02.002. PMID 26975749.

- Sumpton, JE; Moulin, DE (2014). Fibromyalgia. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 119. pp. 513–27. doi:10.1016/B978-0-7020-4086-3.00033-3. ISBN 9780702040863. PMID 24365316.

- Häuser W, Eich W, Herrmann M, Nutzinger DO, Schiltenwolf M, Henningsen P (June 2009). "Fibromyalgia syndrome: classification, diagnosis, and treatment". Dtsch Arztebl Int. 106 (23): 383–91. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2009.0383. PMC 2712241. PMID 19623319.

- Wang, SM; Han, C; Lee, SJ; Patkar, AA; Masand, PS; Pae, CU (June 2015). "Fibromyalgia diagnosis: a review of the past, present and future". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 15 (6): 667–79. doi:10.1586/14737175.2015.1046841. PMID 26035624.

- Bergmann, Uri (2012). Neurobiological foundations for EMDR practice. New York, NY: Springer Pub. Co. p. 165. ISBN 9780826109385.

- Clauw DJ, Arnold LM, McCarberg BH (September 2011). "The science of fibromyalgia". Mayo Clin Proc. 86 (9): 907–11. doi:10.4065/mcp.2011.0206. PMC 3258006. PMID 21878603.

- Müller W, Schneider EM, Stratz T (September 2007). "The classification of fibromyalgia syndrome". Rheumatol Int. 27 (11): 1005–10. doi:10.1007/s00296-007-0403-9. PMID 17653720.

- Hawkins RA (September 2013). "Fibromyalgia: A Clinical Update". Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 113 (9): 680–689. doi:10.7556/jaoa.2013.034. PMID 24005088.

- "Information on Fibromyalgia". Healthline.com. 21 August 2012. Archived from the original on 4 January 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- Wallace DJ, Hallegua DS (October 2002). "Fibromyalgia: the gastrointestinal link". Curr Pain Headache Rep. 8 (5): 364–8. doi:10.1007/s11916-996-0009-z. PMID 15361320.

- Moldofsky H, Scarisbrick P, England R, Smythe H (1975). "Musculoskeletal symptoms and non-REM sleep disturbance in patients with "fibrositis syndrome" and healthy subjects". Psychosom Med. 37 (4): 341–51. doi:10.1097/00006842-197507000-00008. PMID 169541. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- Glass JM (December 2006). "Cognitive dysfunction in fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome: new trends and future directions". Curr Rheumatol Rep. 8 (6): 425–9. doi:10.1007/s11926-006-0036-0. PMID 17092441.

- Leavitt F, Katz RS, Mills M, Heard AR (2002). "Cognitive and Dissociative Manifestations in Fibromyalgia". J Clin Rheumatol. 8 (2): 77–84. doi:10.1097/00124743-200204000-00003. PMID 17041327.

- Buskila D, Cohen H (October 2007). "Comorbidity of fibromyalgia and psychiatric disorders". Curr Pain Headache Rep. 11 (5): 333–8. doi:10.1007/s11916-007-0214-4. PMID 17894922.

- Yunus MB (June 2007). "Role of central sensitization in symptoms beyond muscle pain, and the evaluation of a patient with widespread pain". Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 21 (3): 481–97. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2007.03.006. PMID 17602995.

- Maletic V, Raison CL (2009). "Neurobiology of depression, fibromyalgia and neuropathic pain". Front Biosci. 14: 5291–338. doi:10.2741/3598. PMID 19482616.

- Cohen H, Buskila D, Neumann L, Ebstein RP (March 2002). "Confirmation of an association between fibromyalgia and serotonin transporter promoter region (5- HTTLPR) polymorphism, and relationship to anxiety-related personality traits". Arthritis Rheum. 46 (3): 845–7. doi:10.1002/art.10103. PMID 11920428.

- Buskila D, Dan B, Cohen H, Hagit C, Neumann L, Lily N, Ebstein RP (August 2004). "An association between fibromyalgia and the dopamine D4 receptor exon III repeat polymorphism and relationship to novelty seeking personality traits". Mol. Psychiatry. 9 (8): 730–1. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001506. PMID 15052273.

- Zubieta JK, Heitzeg MM, Smith YR, Bueller JA, Xu K, Xu Y, Koeppe RA, Stohler CS, Goldman D (February 2003). "COMT val158met genotype affects mu-opioid neurotransmitter responses to a pain stressor". Science. 299 (5610): 1240–3. doi:10.1126/science.1078546. PMID 12595695.

- Narita M, Nishigami N, Narita N, Yamaguti K, Okado N, Watanabe Y, Kuratsune H (November 2003). "Association between serotonin transporter gene polymorphism and chronic fatigue syndrome". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 311 (2): 264–6. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.09.207. PMID 14592408.

- Camilleri M, Atanasova E, Carlson PJ, Ahmad U, Kim HJ, Viramontes BE, McKinzie S, Urrutia R (August 2002). "Serotonin-transporter polymorphism pharmacogenetics in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome". Gastroenterology. 123 (2): 425–32. doi:10.1053/gast.2002.34780. PMID 12145795.

- Hudson JI, Mangweth B, Pope HG, De Col C, Hausmann A, Gutweniger S, Laird NM, Biebl W, Tsuang MT (February 2003). "Family study of affective spectrum disorder". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 60 (2): 170–7. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.170. PMID 12578434.

- Lee YH, Choi SJ, Ji JD, Song GG (February 2012). "Candidate gene studies of fibromyalgia: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Rheumatol. Int. 32 (2): 417–26. doi:10.1007/s00296-010-1678-9. PMID 21120487.

- Anderberg UM, Marteinsdottir I, Theorell T, von Knorring L (August 2000). "The impact of life events in female patients with fibromyalgia and in female healthy controls". Eur Psychiatry. 15 (5): 33–41. doi:10.1016/S0924-9338(00)00397-7. PMID 10954873.

- Schweinhardt, Petra; Sauro, Khara M.; Bushnell, M. Catherine (1 October 2008). "Fibromyalgia: a disorder of the brain?". The Neuroscientist: A Review Journal Bringing Neurobiology, Neurology and Psychiatry. 14 (5): 415–421. doi:10.1177/1073858407312521. ISSN 1073-8584. PMID 18270311. S2CID 16654849.

- Häuser W, Kosseva M, Üceyler N, Klose P, Sommer C (2011). "Emotional, physical, and sexual abuse in fibromyalgia syndrome: A systematic review with meta-analysis". Arthritis Care & Research. 63 (6): 808–820. doi:10.1002/acr.20328. PMID 20722042.

- Sommer C, Häuser W, Burgmer M, Engelhardt R, Gerhold K, Petzke F, Schmidt-Wilcke T, Späth M, Tölle T, Uçeyler N, Wang H, Winkelmann A, Thieme K (June 2012). "[Etiology and pathophysiology of fibromyalgia syndrome]". Schmerz. 26 (3): 259–67. doi:10.1007/s00482-012-1174-0. PMID 22760458.

- Afari, Niloofar; Ahumada, Sandra M.; Wright, Lisa Johnson; Mostoufi, Sheeva; Golnari, Golnaz; Reis, Veronica; Cuneo, Jessica Gundy (21 January 2017). "Psychological Trauma and Functional Somatic Syndromes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Psychosomatic Medicine. 76 (1): 2–11. doi:10.1097/PSY.0000000000000010. ISSN 0033-3174. PMC 3894419. PMID 24336429.

- McBeth J, Chiu YH, Silman AJ, Ray D, Morriss R, Dickens C, Gupta A, Macfarlane GJ (2005). "Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal stress axis function and the relationship with chronic widespread pain and its antecedents". Arthritis Research & Therapy. 7 (5): R992–R1000. doi:10.1186/ar1772. PMC 1257426. PMID 16207340.

- Clauw, DJ (16 April 2014). "Fibromyalgia: a clinical review". JAMA. 311 (15): 1547–55. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.3266. PMID 24737367. S2CID 43693607.

- Moldofsky H, Scarisbrick P (January–February 1976). "Induction of neurasthenic musculoskeletal pain syndrome by selective sleep stage deprivation". Psychosomatic Medicine. 38 (1): 35–44. doi:10.1097/00006842-197601000-00006. PMID 176677.

- Mork, Paul J.; Nilsen, Tom I. L. (2012). "Sleep problems and risk of fibromyalgia: Longitudinal data on an adult female population in Norway". Arthritis & Rheumatism. 64 (1): 281–284. doi:10.1002/art.33346. PMID 22081440. S2CID 13274649.

- Goldenberg DL (April 1999). "Fibromyalgia syndrome a decade later: what have we learned?". Arch. Intern. Med. 159 (8): 777–85. doi:10.1001/archinte.159.8.777. PMID 10219923.

- Geoffroy PA, Amad A, Gangloff C, Thomas P (May 2012). "Fibromyalgia and psychiatry: 35 years later… what's new?". Presse Méd. 41 (5): 555–65. doi:10.1016/j.lpm.2011.08.008. PMID 21993145.

- Pae CU, Luyten P, Marks DM, Han C, Park SH, Patkar AA, Masand PS, Van Houdenhove B (August 2008). "The relationship between fibromyalgia and major depressive disorder: a comprehensive review". Curr Med Res Opin. 24 (8): 2359–71. doi:10.1185/03007990802288338. PMID 18606054.

- Giesecke T, Gracely RH, Williams DA, Geisser ME, Petzke FW, Clauw DJ (May 2005). "The relationship between depression, clinical pain, and experimental pain in a chronic pain cohort" (PDF). Arthritis Rheum. 52 (5): 1577–84. doi:10.1002/art.21008. hdl:2027.42/39113. PMID 15880832.

- Alciati A, Sarzi-Puttini P, Batticiotto A, Torta R, Gesuele F, Atzeni F, Angst J (2012). "Overactive lifestyle in patients with fibromyalgia as a core feature of bipolar spectrum disorder". Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 30 (6): 122–128. PMID 23261011.

- Rossi A, Di Lollo AC, Guzzo MP, Giacomelli C, Atzeni F, Bazzichi L, Di Franco M (2015). "Fibromyalgia and nutrition: what news?". Clin Exp Rheumatol. 33 (1 Suppl 88): S117–25. PMID 25786053.

- San Mauro Martín I, Garicano Vilar E, Collado Yurrutia L, Ciudad Cabañas MJ (December 2014). "[Is gluten the great etiopathogenic agent of disease in the XXI century?] [Article in Spanish]". Nutr Hosp. 30 (6): 1203–10. doi:10.3305/nh.2014.30.6.7866. PMID 25433099.

- Bradley, Laurence A. (20 January 2017). "Pathophysiology of Fibromyalgia". The American Journal of Medicine. 122 (12 Suppl): S22–30. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.09.008. ISSN 0002-9343. PMC 2821819. PMID 19962493.

- Solitar, Bruce M. (1 January 2010). "Fibromyalgia: knowns, unknowns, and current treatment". Bulletin of the NYU Hospital for Joint Diseases. 68 (3): 157–161. ISSN 1936-9727. PMID 20969544.

- Bellato, Enrico; Marini, Eleonora; Castoldi, Filippo; Barbasetti, Nicola; Mattei, Lorenzo; Bonasia, Davide Edoardo; Blonna, Davide (1 January 2012). "Fibromyalgia Syndrome: Etiology, Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment". Pain Research and Treatment. 2012: 426130. doi:10.1155/2012/426130. ISSN 2090-1542. PMC 3503476. PMID 23213512.

- Dadabhoy, Dina; Clauw, Daniel J. (1 July 2006). "Therapy Insight: fibromyalgia—a different type of pain needing a different type of treatment". Nature Clinical Practice Rheumatology. 2 (7): 364–372. doi:10.1038/ncprheum0221. ISSN 1745-8382. PMID 16932722.

- Marks, David M; Shah, Manan J; Patkar, Ashwin A; Masand, Prakash S; Park, Geun-Young; Pae, Chi-Un (20 January 2017). "Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors for Pain Control: Premise and Promise". Current Neuropharmacology. 7 (4): 331–336. doi:10.2174/157015909790031201. ISSN 1570-159X. PMC 2811866. PMID 20514212.

- Lin, Chemin; Lee, Shwu-Hua; Weng, Hsu-Huei (1 January 2016). "Gray Matter Atrophy within the Default Mode Network of Fibromyalgia: A Meta-Analysis of Voxel-Based Morphometry Studies". BioMed Research International. 2016: 7296125. doi:10.1155/2016/7296125. ISSN 2314-6141. PMC 5220433. PMID 28105430.

- Napadow, Vitaly; Harris, Richard E (1 January 2014). "What has functional connectivity and chemical neuroimaging in fibromyalgia taught us about the mechanisms and management of 'centralized' pain?". Arthritis Research & Therapy. 16 (4): 425. doi:10.1186/s13075-014-0425-0. ISSN 1478-6354. PMC 4289059. PMID 25606591.

- Dell'Osso, Liliana; Bazzichi, Laura; Baroni, Stefano; Falaschi, Valentina; Conversano, Ciro; Carmassi, Claudia; Marazziti, Donatella (1 January 2015). "The inflammatory hypothesis of mood spectrum broadened to fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome". Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 33 (1 Suppl 88): S109–116. ISSN 0392-856X. PMID 25786052.

- Rodriguez-Pintó, Ignasi; Agmon-Levin, Nancy; Howard, Amital; Shoenfeld, Yehuda (1 October 2014). "Fibromyalgia and cytokines". Immunology Letters. 161 (2): 200–203. doi:10.1016/j.imlet.2014.01.009. ISSN 1879-0542. PMID 24462815.

- Littlejohn, Geoffrey (1 November 2015). "Neurogenic neuroinflammation in fibromyalgia and complex regional pain syndrome". Nature Reviews. Rheumatology. 11 (11): 639–648. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2015.100. ISSN 1759-4804. PMID 26241184.

- Uçeyler, Nurcan; Häuser, Winfried; Sommer, Claudia (28 October 2011). "Systematic review with meta-analysis: cytokines in fibromyalgia syndrome". BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 12: 245. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-12-245. ISSN 1471-2474. PMC 3234198. PMID 22034969.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 8 April 2011. Retrieved 4 May 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Fibromyalgia". Archived from the original on 17 June 2013. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- Wolfe F (August 2003). "Stop using the American College of Rheumatology criteria in the clinic". J. Rheumatol. 30 (8): 1671–2. PMID 12913920. Archived from the original on 14 October 2011.

- Wolfe, F; et al. (May 2010). "The American College of Rheumatology Preliminary Diagnostic Criteria for Fibromyalgia and Measurement of Symptom Severity". Arthritis Care Res. 62 (5): 600–610. doi:10.1002/acr.20140. hdl:2027.42/75772. PMID 20461783.

- Wang, Sheng-Min; Han, Changsu; Lee, Soo-Jung; Patkar, Ashwin A.; Masand, Prakash S.; Pae, Chi-Un (3 June 2015). "Fibromyalgia diagnosis: a review of the past, present and future". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 15 (6): 667–679. doi:10.1586/14737175.2015.1046841. ISSN 1473-7175. PMID 26035624.

- Bennett, Robert M.; Friend, Ronald; Jones, Kim D.; Ward, Rachel; Han, Bobby K.; Ross, Rebecca L. (1 January 2009). "The Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQR): validation and psychometric properties". Arthritis Research & Therapy. 11 (4): R120. doi:10.1186/ar2783. ISSN 1478-6354. PMC 2745803. PMID 19664287.

- Wolfe, Frederick; Clauw, Daniel J.; Fitzcharles, Mary-Ann; Goldenberg, Don L.; Katz, Robert S.; Mease, Philip; Russell, Anthony S.; Russell, I. Jon; Winfield, John B. (1 May 2010). "The American College of Rheumatology Preliminary Diagnostic Criteria for Fibromyalgia and Measurement of Symptom Severity". Arthritis Care & Research. 62 (5): 600–610. doi:10.1002/acr.20140. hdl:2027.42/75772. ISSN 2151-4658. PMID 20461783.

- Seidenberg, Michael; Haltiner, Alan; Taylor, Michael; Hermann, Bruce; Wyler, Allen (2008). "Development and validation of a multiple ability self-report questionnaire". Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 16 (1): 93–104. doi:10.1080/01688639408402620. PMID 8150893.

- Goldenberg DL (2009). "Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of fibromyalgia". Am J Med (Review). 122 (12 Suppl): S14–21. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.09.007. PMID 19962492.

- Marchesoni A, De Marco G, Merashli M, McKenna F, Tinazzi I, Marzo-Ortega H, et al. (2018). "The problem in differentiation between psoriatic-related polyenthesitis and fibromyalgia" (PDF). Rheumatology (Oxford) (Review). 57 (1): 32–40. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kex079. PMID 28387854.

- Palazzi C, D'Amico E, D'Angelo S, Gilio M, Olivieri I (2016). "Rheumatic manifestations of hepatitis C virus chronic infection: Indications for a correct diagnosis". World J Gastroenterol (Review). 22 (4): 1405–10. doi:10.3748/wjg.v22.i4.1405. PMC 4721975. PMID 26819509.

- Goldenberg DL (2008). "Multidisciplinary modalities in the treatment of fibromyalgia". J Clin Psychiatry. 69 (2): 30–4. PMID 18537461.

- Sommer C, Häuser W, Alten R, Petzke F, Späth M, Tölle T, Uçeyler N, Winkelmann A, Winter E, Bär KJ (June 2012). "Drug therapy of fibromyalgia syndrome. Systematic review, meta-analysis and guideline" (PDF). Schmerz. 26 (3): 297–310. doi:10.1007/s00482-012-1172-2. PMID 22760463. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2013.

- Carville SF, Arendt-Nielsen S, Bliddal H, Blotman F, Branco JC, Buskila D, Da Silva JA, Danneskiold-Samsøe B, Dincer F, Henriksson C, Henriksson KG, Kosek E, Longley K, McCarthy GM, Perrot S, Puszczewicz M, Sarzi-Puttini P, Silman A, Späth M, Choy EH (April 2008). "EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia syndrome" (PDF). Ann. Rheum. Dis. 67 (4): 536–41. doi:10.1136/ard.2007.071522. PMID 17644548. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 May 2014. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- 2012 Canadian guidelines for the diagnosis and management of fibromyalgia syndrome Archived 11 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- "FDA Approves First Drug for Treating Fibromyalgia" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 21 June 2007. Archived from the original on 21 February 2008. Retrieved 14 January 2008.

- European Medicines Agency. "Questions and answers on the recommendati on for the refusal of the marketing authorisation for Milnacipran Pierre Fabre Médicament/Impulsor" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- Häuser W, Bernardy K, Uçeyler N, Sommer C (January 2009). "Treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome with antidepressants: a meta-analysis". JAMA. 301 (2): 198–209. doi:10.1001/jama.2008.944. PMID 19141768.

- Häuser W, Wolfe F, Tölle T, Uçeyler N, Sommer C (April 2012). "The role of antidepressants in the management of fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis". CNS Drugs. 26 (4): 297–307. doi:10.2165/11598970-000000000-00000. PMID 22452526.

- Cording, Malene; Derry, Sheena; Phillips, Tudor; Moore, R. Andrew; Wiffen, Philip J. (20 October 2015). "Milnacipran for pain in fibromyalgia in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (10): CD008244. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008244.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6481368. PMID 26482422.

- Moore, RA; Derry, S; Aldington, D; Cole, P; Wiffen, PJ (31 July 2015). "Amitriptyline for fibromyalgia in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 7 (7): CD011824. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011824. PMC 6485478.

- Häuser, Winfried; Walitt, Brian; Fitzcharles, Mary-Ann; Sommer, Claudia (1 January 2014). "Review of pharmacological therapies in fibromyalgia syndrome". Arthritis Research & Therapy. 16 (1): 201. doi:10.1186/ar4441. ISSN 1478-6362. PMC 3979124. PMID 24433463.

- Walitt, Brian; Urrútia, Gerard; Nishishinya, María Betina; Cantrell, Sarah E; Häuser, Winfried (5 June 2015). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for fibromyalgia syndrome". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (6): CD011735. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011735. ISSN 1465-1858. PMC 4755337. PMID 26046493.

- Tort, Sera; Urrútia, Gerard; Nishishinya, María Betina; Walitt, Brian (18 April 2012). "Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) for fibromyalgia syndrome". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD009807. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd009807. ISSN 1465-1858. PMID 22513976.

- Üçeyler N, Sommer C, Walitt B, Häuser W (2013). Häuser W (ed.). "Anticonvulsants for fibromyalgia". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 10 (10): CD010782. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010782. PMID 24129853. (Retracted, see doi:10.1002/14651858.cd010782.pub2. If this is an intentional citation to a retracted paper, please replace

{{Retracted}}with{{Retracted|intentional=yes}}.) - Wiffen, PJ; Derry, S; Bell, RF; Rice, AS; Tölle, TR; Phillips, T; Moore, RA (9 June 2017). "Gabapentin for chronic neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6: CD007938. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007938.pub4. PMC 6452908. PMID 28597471.

- Derry, Sheena; Cording, Malene; Wiffen, Philip J.; Law, Simon; Phillips, Tudor; Moore, R. Andrew (29 September 2016). "Pregabalin for pain in fibromyalgia in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9: CD011790. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011790.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6457745. PMID 27684492.

- Straube S, Moore RA, Paine J, Derry S, Phillips CJ, Hallier E, McQuay HJ (2011). "Interference with work in fibromyalgia – effect of treatment with pregabalin and relation to pain response". BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 12: 125. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-12-125. PMC 3118156. PMID 21639874.

- MacLean, AJ; Schwartz, TL (May 2015). "Tramadol for the treatment of fibromyalgia". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 15 (5): 469–75. doi:10.1586/14737175.2015.1034693. PMID 25896486.

- Thorpe, J; Shum, B; Moore, RA; Wiffen, PJ; Gilron, I (19 February 2018). "Combination pharmacotherapy for the treatment of fibromyalgia in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2: CD010585. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010585.pub2. PMC 6491103. PMID 29457627.

- Ngian GS, Guymer EK, Littlejohn GO (February 2011). "The use of opioids in fibromyalgia". Int J Rheum Dis. 14 (1): 6–11. doi:10.1111/j.1756-185X.2010.01567.x. PMID 21303476.

- Berger A. Patterns of use of opioids in patients with fibromyalgia In: EULAR; 2009:SAT0461

- Jones KD, Deodhar P, Lorentzen A, Bennett RM, Deodhar AA (2007). "Growth hormone perturbations in fibromyalgia: a review". Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 36 (6): 357–79. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.09.006. PMID 17224178.

- Cuatrecasas, G.; Alegre, C.; Casanueva, FF. (June 2014). "GH/IGF1 axis disturbances in the fibromyalgia syndrome: is there a rationale for GH treatment?". Pituitary. 17 (3): 277–83. doi:10.1007/s11102-013-0486-0. PMID 23568565.

- Staud R (August 2011). "Sodium oxybate for the treatment of fibromyalgia". Expert Opin Pharmacother. 12 (11): 1789–98. doi:10.1517/14656566.2011.589836. PMID 21679091.

- See S, Ginzburg R (1 August 2008). "Choosing a Skeletal Muscle Relaxant". Am Fam Physician. 78 (3): 365–70. PMID 18711953. Archived from the original on 1 April 2016.

- Kaltsas, Gregory; Tsiveriotis, Konstantinos (2000). "Fibromyalgia". Endotext. MDText.com, Inc.

- Heymann RE, Paiva Edos S, Helfenstein M, Pollak DF, Martinez JE, Provenza JR, Paula AP, Althoff AC, Souza EJ, Neubarth F, Lage LV, Rezende MC, de Assis MR, Lopes ML, Jennings F, Araújo RL, Cristo VV, Costa ED, Kaziyama HH, Yeng LT, Iamamura M, Saron TR, Nascimento OJ, Kimura LK, Leite VM, Oliveira J, de Araújo GT, Fonseca MC (2010). "Brazilian consensus on the treatment of fibromyalgia". Rev Bras Reumatol. 50 (1): 56–66. doi:10.1590/S0482-50042010000100006. PMID 21125141.

- Derry, S; Wiffen, PJ; Häuser, W; Mücke, M; Tölle, TR; Bell, RF; Moore, RA (27 March 2017). "Oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for fibromyalgia in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3: CD012332. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012332.pub2. PMC 6464559. PMID 28349517.

- Holman AJ, Myers RR (August 2005). "A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of pramipexole, a dopamine agonist, in patients with fibromyalgia receiving concomitant medications". Arthritis & Rheumatism. 52 (8): 2495–505. doi:10.1002/art.21191. PMID 16052595.

- Holman AJ (September 2009). "Impulse control disorder behaviors associated with pramipexole used to treat fibromyalgia". J Gambl Stud. 25 (3): 425–31. doi:10.1007/s10899-009-9123-2. PMID 19241148.

- Späth, M (May 2002). "Current experience with 5-HT3 receptor antagonists in fibromyalgia". Rheumatic Diseases Clinics of North America. 28 (2): 319–28. doi:10.1016/s0889-857x(01)00014-x. PMID 12122920.

- Younger J, Parkitny L, McLain D (2014). "The use of low-dose naltrexone (LDN) as a novel anti-inflammatory treatment for chronic pain". Clin Rheumatol. 33 (4): 451–459. doi:10.1007/s10067-014-2517-2. PMC 3962576. PMID 24526250.

- Walitt, Brian; Klose, Petra; Üçeyler, Nurcan; Phillips, Tudor; Häuser, Winfried (2 June 2016). "Antipsychotics for fibromyalgia in adults". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (6): CD011804. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011804.pub2. PMC 6457603. PMID 27251337.

- Walitt, Brian; Klose, Petra; Fitzcharles, Mary-Ann; Phillips, Tudor; Häuser, Winfried (18 July 2016). "Cannabinoids for fibromyalgia". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 7: CD011694. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011694.pub2. PMC 6457965. PMID 27428009.

- Pope, Janet; Fenlon, D; Thompson, A; Shea, Beverley; Furst, Dan; Wells, George A; Silman, Alan (27 April 1998). "Iloprost and cisaprost for Raynaud's phenomenon in progressive systemic sclerosis". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD000953. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd000953. ISSN 1465-1858. PMC 7032888. PMID 10796395.

- Pridgen, William L.; Duffy, Carol; Gendreau, Judy F.; Gendreau, R. Michael (2017). "A famciclovir + celecoxib combination treatment is safe and efficacious in the treatment of fibromyalgia". Journal of Pain Research. 10: 451–460. doi:10.2147/JPR.S127288. ISSN 1178-7090. PMC 5328426. PMID 28260944.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Arnold, L.M.; Gebke, K.B.; Choy, E.H.S. (2016). "Fibromyalgia: Management strategies for primary care providers". The International Journal of Clinical Practice. 70 (2): 99–112. doi:10.1111/ijcp.12757. PMC 6093261. PMID 26817567.

- Clauw, D. (2014). "Fibromyalgia: A clinical review". Journal of the American Medical Association. 311 (15): 1547–1555. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.3266. PMID 24737367. S2CID 43693607.

- Okifuji, A.; Hare, B.D. (2013). "Management of fibromyalgia syndrome: Review of evidence". Pain Therapy. 2 (2): 87–104. doi:10.1007/s40122-013-0016-9. PMC 4107911. PMID 25135147.

- Williams, A.C.D.; Eccleston, C.; Morley, S. (2009). "Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11: 108–111. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007407.pub3. PMC 6483325. PMID 23152245.

- Abeles, M.; Solitar, B.M.; Pillinger, M.H.; Abeles, A.M. (2008). "Update of fibromyalgia therapy". American Journal of Medicine. 121 (7): 555–561. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.02.036. PMID 18589048.

- Hauser W, Bernardy K, Arnold B, Offenbacher M, Schiltenwolf M (2009). "Efficacy of multicomponent treatment in fibromyalgia syndrome: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials". Arthritis Care & Research. 61 (2): 216–224. doi:10.1002/art.24276. PMID 19177530. S2CID 22580742.

- Karjalainen, Kaija A; Malmivaara, Antti; van Tulder, Maurits W; Roine, Risto; Jauhiainen, Merja; Hurri, Heikki; Koes, Bart W (26 July 1999). "Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for fibromyalgia and musculoskeletal pain in working age adults". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD001984. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd001984. ISSN 1465-1858. PMID 10796458.

- Arnold, L.M.; Clauw, D.; Dunegan, J.; Turk, D.C. (2012). "A framework for fibromyalgia management for primary care providers". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 87 (5): 488–496. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.02.010. PMC 3498162. PMID 22560527.

- Glombiewski, J.A.; Sawyer, A.T.; Gutermann, A.T.; Koenig, K.; Rief, W.; Hofmann, S.G. (2010). "Psychological treatments for fibromyalgia: A meta-analysis". Pain. 151 (2): 280–295. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2010.06.011. PMID 20727679.

- Okifuji, A.; Hare, B.C. (2013). "Management of fibromyalgia syndrome: Review of evidence". Pain Therapy. 2 (2): 87–104. doi:10.1007/s40122-013-0016-9. PMC 4107911. PMID 25135147.

- Howard, S.; Smith, M.D.; Barkin, R.L. (2011). "Fibromyalgia syndrome: a discussionof the syndrome and pharmacotherapy". American Journal of Therapeutics. 17 (4): 418–439. doi:10.1097/MJT.0b013e3181df8e1b. PMID 20562596.

- Bernardy K, Klose P, Busch AJ, Choy EH, Häuser W (10 September 2013). "Cognitive behavioral therapies for fibromyalgia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9 (9): CD009796. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009796.pub2. PMC 6481397. PMID 24018611.

- Glombiewski, J.A.; Sawyer, A.T.; Gutermann, A.T.; Koenig, K.; Rief, W.; Hofmann, S.G. (2010). "Psychological treatments for fibromyalgia: A meta analysis". Pain. 151 (2): 280–295. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2010.06.011. PMID 20727679.

- Williams DA (August 2003). "Psychological and behavioral therapies in fibromyalgia and related syndromes". Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 17 (4): 649–65. doi:10.1016/S1521-6942(03)00034-2. PMID 12849717.

- Bernardy K, Füber N, Köllner V, Häuser W (October 2010). "Efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapies in fibromyalgia syndrome – a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". J. Rheumatol. 37 (10): 1991–2005. doi:10.3899/jrheum.100104. PMID 20682676. S2CID 11357808.

- Theadom, Alice; Cropley, Mark; Smith, Helen E.; Feigin, Valery L.; McPherson, Kathryn (9 April 2015). "Mind and body therapy for fibromyalgia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD001980. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001980.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 25856658.

- Busch, A. J.; Barber, K. a. R.; Overend, T. J.; Peloso, P. M. J.; Schachter, C. L. (17 October 2007). "Exercise for treating fibromyalgia syndrome". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD003786. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003786.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 17943797.

- Gowans SE, deHueck A (2004). "Effectiveness of exercise in management of fibromyalgia". Current Opinion in Rheumatology. 16 (2): 138–42. doi:10.1097/00002281-200403000-00012. PMID 14770100.

- Goldenberg DL, Burckhardt C, Crofford L (November 2004). "Management of fibromyalgia syndrome". Journal of the American Medical Association. 292 (19): 2388–2395. doi:10.1001/jama.292.19.2388. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 15547167.

- Busch, Angela J; Webber, Sandra C; Richards, Rachel S; Bidonde, Julia; Schachter, Candice L; Schafer, Laurel A; Danyliw, Adrienne; Sawant, Anuradha; Dal Bello-Haas, Vanina (20 December 2013). "Resistance exercise training for fibromyalgia". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD010884. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd010884. ISSN 1465-1858. PMC 6544808. PMID 24362925.

- Bidonde, Julia; Busch, Angela J.; Schachter, Candice L.; Overend, Tom J.; Kim, Soo Y.; Góes, Suelen M.; Boden, Catherine; Foulds, Heather JA (21 June 2017). "The Cochrane Library". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6: CD012700. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd012700. PMC 6481524. PMID 28636204.

- Bidonde, Julia; Busch, Angela J; Schachter, Candice L; Webber, Sandra C; Musselman, Kristin E; Overend, Tom J; Góes, Suelen M; Dal Bello-Haas, Vanina; Boden, Catherine (24 May 2019). "Mixed exercise training for adults with fibromyalgia". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5: CD013340. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd013340. ISSN 1465-1858. PMC 6931522. PMID 31124142.

- Bidonde, Julia; Busch, Angela J; Webber, Sandra C; Schachter, Candice L; Danyliw, Adrienne; Overend, Tom J; Richards, Rachel S; Rader, Tamara (28 October 2014). "Aquatic exercise training for fibromyalgia". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (10): CD011336. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011336. ISSN 1465-1858. PMID 25350761.

- Ryan S (2013). "Care of patients with fibromyalgia: Assessment and management". Nursing Standard. 28 (13): 37–43. doi:10.7748/ns2013.11.28.13.37.e7722. PMID 24279570.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 20 February 2014. Retrieved 2 February 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Bidonde, Julia; Busch, Angela J; van der Spuy, Ina; Tupper, Susan; Kim, Soo Y; Boden, Catherine (26 September 2017). "Whole body vibration exercise training for fibromyalgia". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9: CD011755. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011755.pub2. ISSN 1465-1858. PMC 6483692. PMID 28950401.

- Goldenberg DL, Mossey CJ, Schmid CH (December 1995). "A model to assess severity and impact of fibromyalgia". J. Rheumatol. 22 (12): 2313–8. PMID 8835568.

- Chakrabarty S, Zoorob R (July 2007). "Fibromyalgia". American Family Physician. 76 (2): 247–254. PMID 17695569. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 6 January 2008.

- Health Information Team (February 2004). "Fibromyalgia". BUPA insurance. Archived from the original on 22 June 2006. Retrieved 24 August 2006.

- Yunus M, Masi AT, Calabro JJ, Miller KA, Feigenbaum SL (August 1981). "Primary fibromyalgia (fibrositis): clinical study of 50 patients with matched normal controls". Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 11 (1): 151–171. doi:10.1016/0049-0172(81)90096-2. ISSN 0049-0172. PMID 6944796.

- "Fibro-". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 13 December 2009. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- "Meaning of myo". 12 April 2009. Archived from the original on 12 April 2009. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- "Meaning of algos". 12 April 2009. Archived from the original on 12 April 2009. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- Wolfe F (2009). "Fibromyalgia wars". J. Rheumatol. 36 (4): 671–8. doi:10.3899/jrheum.081180. PMID 19342721.

- Smythe HA, Moldofsky H (1977). "Two contributions to understanding of the "fibrositis" syndrome". Bull Rheum Dis. 28 (1): 928–31. PMID 199304.

- Winfield JB (June 2007). "Fibromyalgia and related central sensitivity syndromes: twenty-five years of progress". Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 36 (6): 335–8. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.12.001. PMID 17303220.

- Inanici F, Yunus MB (October 2004). "History of fibromyalgia: past to present". Curr Pain Headache Rep. 8 (5): 369–78. doi:10.1007/s11916-996-0010-6. PMID 15361321.

- Goldenberg DL (May 1987). "Fibromyalgia syndrome. An emerging but controversial condition". JAMA. 257 (20): 2782–7. doi:10.1001/jama.257.20.2782. PMID 3553636.

- Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, Bennett RM, Bombardier C, Goldenberg DL, Tugwell P, Campbell SM, Abeles M, Clark P (February 1990). "The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee". Arthritis Rheum. 33 (2): 160–72. doi:10.1002/art.1780330203. PMID 2306288.

- "High health care utilization and costs in patients with fibromyalgia". Drug Benefit Trends. 22 (4): 111. 2010. Archived from the original on 29 October 2012. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- Berenson (14 January 2008). "Drug Approved. Is Disease Real?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 May 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- "Fibromyalgia: An interview with Dr Frederick Wolfe, University of Kansas School of Medicine". 22 March 2013. Archived from the original on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- Goldenberg DL (January 1995). "Fibromyalgia: why such controversy?". Ann. Rheum. Dis. 54 (1): 3–5. doi:10.1136/ard.54.1.3. PMC 1005499. PMID 7880118.

- Kroenke K, Harris L (May 2001). "Symptoms research: a fertile field". Annals of Internal Medicine. 134 (9 Pt 2): 801–802. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-134-9_Part_2-200105011-00001. ISSN 0003-4819. PMID 11346313.

- Kanaan RA, Lepine JP, Wessely SC (December 2007). "The association or otherwise of the functional somatic syndromes". Psychosom Med. 69 (9): 855–9. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e31815b001a. PMC 2575798. PMID 18040094.

- Wood PB, Holman AJ, Jones KD (June 2007). "Novel pharmacotherapy for fibromyalgia". Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 16 (6): 829–41. doi:10.1517/13543784.16.6.829. PMID 17501695.

- Aziz, I; Hadjivassiliou, M; Sanders, DS (September 2015). "The spectrum of noncoeliac gluten sensitivity". Nature Reviews. Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 12 (9): 516–26. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2015.107. PMID 26122473.

- Bennett RM, De Garmo P, Clark SR (1996). "A Randomized, Prospective, 12 Month Study To Compare The Efficacy Of Guaifenesin Versus Placebo In The Management Of Fibromyalgia" (reprint). Arthritis and Rheumatism. 39 (10): 1627–1634. doi:10.1002/art.1780391004. PMID 8843852. Archived from the original on 9 February 2014.

- Kristin Thorson (1997). "Is One Placebo Better Than Another? – The Guaifenesin Story (Lay summary and report)". Fibromyalgia Network. Fibromyalgia Network. Archived from the original on 23 October 2011.

- Marco L.Loggia, Daniel S.Albrechta (14 September 2018). "Brain glial activation in fibromyalgia". Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 75: 72–83. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2018.09.018. PMC 6541932. PMID 30223011.

External links

- Fibromyalgia at Curlie

- Arthritis – Types – Fibromyalgia by the CDC

- Questions and Answers About Fibromyalgia by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |