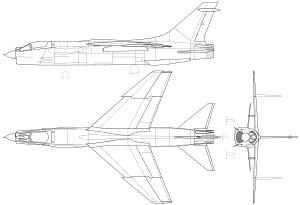

Vought F-8 Crusader

The Vought F-8 Crusader (originally F8U) is a single-engine, supersonic, carrier-based air superiority jet aircraft[2] built by Vought for the United States Navy and United States Marine Corps (replacing the Vought F7U Cutlass), and for the French Navy. The first F-8 prototype was ready for flight in February 1955. The F-8 served principally in the Vietnam War. The Crusader was the last American fighter with guns as the primary weapon, earning it the title "The Last of the Gunfighters".[3]

| F-8 (F8U) Crusader | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| An F-8E from VMF(AW)-212 in 1965 | |

| Role | Fighter aircraft |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Vought |

| First flight | 25 March 1955 |

| Introduction | March 1957 |

| Retired | 1976 (fighter, U.S. Navy) 29 March 1987 (photo reconnaissance, U.S. Naval Reserve) 1991 (Philippines) 19 December 1999 (fighter, French Naval Aviation) |

| Status | Retired completely in 1999 |

| Primary users | United States Navy United States Marine Corps French Navy Philippine Air Force |

| Number built | 1,219[1] |

| Developed into | Vought XF8U-3 Crusader III LTV A-7 Corsair II |

The RF-8 Crusader was a photo-reconnaissance development and operated longer in U.S. service than any of the fighter versions. RF-8s played a crucial role in the Cuban Missile Crisis, providing essential low-level photographs impossible to acquire by other means.[3] United States Navy Reserve units continued to operate the RF-8 until 1987.

Design and development

In September 1952, the United States Navy announced a requirement for a new fighter. It was to have a top speed of Mach 1.2 at 30,000 ft (9,144.0 m) with a climb rate of 25,000 ft/min (127.0 m/s), and a landing speed of no more than 100 mph (160 km/h).[4] Korean War experience had demonstrated that 0.50 inch (12.7 mm) machine guns were no longer sufficient and as the result the new fighter was to carry a 20 mm (0.79 in) cannon. In response, the Vought team led by John Russell Clark, created the V-383. Unusual for a fighter, the aircraft had a high-mounted wing which necessitated the use of a fuselage-mounted short and light landing gear.

The Crusader was powered by a Pratt and Whitney J57 turbojet engine. The engine was equipped with an afterburner that, unlike on later engines, was either fully lit, or off (i.e. it did not have "zones"). The engine produced 18,000 lb of thrust at full power, enough to allow the F-8 to climb straight up in clean configuration. The Crusader was the first jet fighter in US service to reach 1,000 mph; U.S. Navy pilot R.W. Windsor reached 1,015 mph on a flight in 1956.[5]

The most innovative aspect of the design was the variable-incidence wing which pivoted by 7° out of the fuselage on takeoff and landing (not to be confused with variable-sweep wing). This allowed a greater angle of attack, increasing lift without compromising forward visibility.[3][4] This innovation helped the F-8's development team win the Collier Trophy in 1956.[6] Simultaneously, the lift was augmented by leading-edge slats drooping by 25° and inboard flaps extending to 30°. The rest of the aircraft took advantage of contemporary aerodynamic innovations with area-ruled fuselage, all-moving stabilators, dog-tooth notching at the wing folds for improved yaw stability, and liberal use of titanium in the airframe. The armament, as specified by the Navy, consisted primarily of four 20 mm (.79 in) autocannons; the Crusader happened to be the last U.S. fighter designed with guns as its primary weapon.[3] They were supplemented with a retractable tray with 32 unguided Mk 4/Mk 40 Folding-Fin Aerial Rocket (Mighty Mouse FFARs), and cheek pylons for two guided AIM-9 Sidewinder air-to-air missiles.[4] In practice, AIM-9 Sidewinder missiles were the F-8's primary weapon; the 20mm guns were "generally unreliable." Moreover, it achieved nearly all of its kills with Sidewinders.[7] Vought also presented a tactical reconnaissance version of the aircraft called the V-392.

Major competition came from the Grumman F-11 Tiger, the upgraded twin-engine McDonnell F3H Demon (which would eventually become the McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II), and lastly, the North American F-100 Super Sabre hastily adapted to carrier use and dubbed the "Super Fury".

In May 1953, the Vought design was declared a winner and in June, Vought received an order for three XF8U-1 prototypes (after adoption of the unified designation system in September 1962, the F8U became the F-8). The first prototype flew on 25 March 1955 with John Konrad at the controls. The aircraft exceeded the speed of sound during its maiden flight.[3] The development was so trouble-free that the second prototype, along with the first production F8U-1, flew on the same day, 30 September 1955. On 4 April 1956, the F8U-1 performed its first catapult launch from Forrestal.

Crusader III

In parallel with the F8U-1s and -2s, the Crusader design team was also working on a larger aircraft with ever-greater performance, internally designated as the V-401. Although the Vought XF8U-3 Crusader III was externally similar to the Crusader and sharing with it such design elements as the variable incidence wing, the new fighter was larger and shared few components.

Operational history

_launches_Vought_F-8_Crusaders_in_1963_(NH_97634).jpg)

Prototype XF8U-1s were evaluated by VX-3 beginning in late 1956, with few problems noted. Weapons development was conducted at Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake and a China Lake F8U-1 set a U.S. National speed record in August 1956. Commander "Duke" Windsor set, broke, and set a new Level Flight Speed Record of 1,015.428 mph (1,634.173 km/h) on 21 August 1956 beating the previous record of 822 mph (1,323 km/h) set by a USAF F-100. (It did not break the world speed record of 1,132 mph (1,822 km/h), set by the British Fairey Delta 2, on 10 March 1956.[8])

An early F8U-1 was modified as a photo-reconnaissance aircraft, becoming the first F8U-1P. Subsequently, the RF-8A was equipped with cameras rather than guns and missiles. On 16 July 1957, Major John H. Glenn Jr, USMC, completed the first supersonic transcontinental flight in a F8U-1P, flying from NAS Los Alamitos, California, to Floyd Bennett Field, New York, in 3 hours, 23 minutes, and 8.3 seconds.[9]

First fleet operators

VX-3 was one of the first units to receive the F8U-1 in December 1956, and was the first to operate the type in April 1957, from USS Franklin D. Roosevelt. VX-3 was the first unit to qualify for carrier operations but several aircraft were lost in accidents, several of them fatal to their pilots.

The first fleet squadron to fly the Crusader was VF-32 at NAS Cecil Field, Florida, in 1957, which deployed to the Mediterranean late that year on Saratoga. VF-32 renamed the squadron the "Swordsmen" in keeping with the Crusader theme. The Pacific Fleet received the first Crusaders at NAS Moffett Field in northern California and the VF-154 "Grandslammers" (named in honor of the new 1,000-mph jets and subsequently renamed the "Black Knights") began their F-8 operations. Later in 1957, in San Diego VMF-122 accepted the first Marine Corps Crusaders.

In 1962, the Defense Department standardized military aircraft designations generally along Air Force lines. Consequently, the F8U became the F-8, with the original F8U-1 redesignated F-8A.

_on_25_May_1974.jpg)

Fleet service

The Crusader became a "day fighter" operating off the aircraft carriers. At the time, U.S. Navy carrier air wings had gone through a series of day and night fighter aircraft due to rapid advances in engines and avionics. Some squadrons operated aircraft for very short periods before being equipped with a newer higher performance aircraft. The Crusader was the first post-Korean War aircraft to have a relatively long tenure with the fleet and like the USAF Republic F-105 Thunderchief, a contemporary design, might have stayed in service longer if not for the Vietnam War and corresponding attrition from combat and operational losses.

Cuban Missile Crisis

The unarmed RF-8A proved good at getting low-altitude detailed photographs, leading to carrier deployments as detachments from the Navy's VFP-62 and VFP-63 squadrons and the Marines' VMCJ-2.[10] Beginning on 23 October 1962 during the Cuban Missile Crisis, RF-8As flew extremely hazardous low-level photo reconnaissance missions over Cuba, the F-8's first true operational flights. Two-ship flights of RF-8As left Key West twice each day, to fly over Cuba at low level, then return to Jacksonville, where the film was offloaded and developed, to be rushed north to the Pentagon.[11]

These flights confirmed that the Soviet Union was setting up IRBMs in Cuba. The RF-8As also monitored the withdrawal of the Soviet missiles. After each overflight, the aircraft was given a stencil of a dead chicken. The overflights went on for about six weeks and returned a total of 160,000 images. The pilots who flew the missions received Distinguished Flying Crosses, while VFP-62 and VMCJ-2 received the prestigious U.S. Navy Unit Commendation.[12]

Mishap rate

The Crusader was not an easy aircraft to fly, and was often unforgiving in carrier landings, where it suffered from poor recovery from high sink rates, and the poorly designed, castering nose undercarriage made it hard to steer on the deck. Safe landings required the carriers to steam at full speed to lower the relative landing speed for Crusader pilots. The stacks of the oil-burning carriers on which the Crusader served belched thick black smoke, sometimes obscuring the flight deck, forcing the Crusader's pilot to rely on the landing signal officer's radioed instructions.[6] It earned a reputation as an "ensign eliminator" during its early service introduction.[13] The nozzle and air intake were so low when the aircraft was on the ground or the flight deck that the crews called the aircraft "the Gator". Not surprisingly, the Crusader's mishap rate was relatively high compared to its contemporaries, the Douglas A-4 Skyhawk and the F-4 Phantom II. However, the aircraft did possess some amazing capabilities, as proved when several Crusader pilots took off with the wings folded. One of these episodes took place on 23 August 1960; a Crusader with the wings folded took off from Napoli Capodichino in full afterburner, climbed to 5,000 ft (1,500 m) and then returned to land successfully. The pilot, absentminded but evidently a good "stick man," complained that the control forces were higher than normal. The Crusader was capable of flying in this state, though the pilot would be required to reduce aircraft weight by ejecting stores and fuel before landing.[3] In all, 1,261 Crusaders were built. By the time it was withdrawn from the fleet, 1,106 had been involved in mishaps.[14]

Vietnam War

When conflict erupted in the skies over North Vietnam, it was U.S. Navy Crusaders from USS Hancock that first tangled with Vietnam People's Air Force (the North Vietnamese Air Force) MiG-17s, on 3 April 1965.[15] The MiGs claimed the downing of a Crusader, and Lt Pham Ngoc Lan's gun camera revealed that his cannons had set an F-8 ablaze, but Lieutenant Commander Spence Thomas had managed to land his damaged Crusader at Da Nang Air Base,[16][17] the remaining F-8s returning safely to their carrier. At the time, the Crusader was the best dogfighter the United States had against the nimble North Vietnamese MiGs. The U.S. Navy had evolved its "night fighter" role in the air wing to an all-weather interceptor, the F-4 Phantom II, equipped to engage incoming bombers at long range with missiles such as AIM-7 Sparrow as their sole air-to-air weapons, and maneuverability was not emphasized in their design. Some experts believed that the era of the dogfight was over as air-to-air missiles would knock down adversaries well before they could get close enough to engage in dogfighting. As aerial combat ensued over North Vietnam from 1965 to 1968, it became apparent that the dogfight was not over and the F-8 Crusader and a community trained to prevail in air-to-air combat was a key ingredient to success.

The Crusader also became a "bomb truck" in war, with both ship-based U.S. Navy units and land-based U.S. Marine Corps squadrons attacking communist forces in both North and South Vietnam.[13]

US Marine Crusaders flew only in the south, while Navy Crusaders flew only from the small Essex-class carriers. Marine Crusaders also operated in close air support missions.

Despite the "last gunfighter" moniker, the F-8s achieved only four victories with their cannon; the remainder were accomplished with AIM-9 Sidewinder missiles,[18] partly due to the propensity of the 20 mm (.79 in) Colt Mk 12 cannons' feeding mechanism to jam under G-loading during high-speed dogfighting maneuvers.[19] Between June and July 1966, during 12 engagements over North Vietnam, Crusaders claimed four MiG-17s for two losses.[20] The Crusader would claim the best kill ratio of any American type in the Vietnam War, 19:3.[3] Of the 19 aircraft claimed during aerial combat, 16 were MiG-17s and three were MiG-21s.[18] U.S. records indicate only three F-8s lost in aerial combat, all to MiG-17 cannon fire in 1966, but the VPAF claimed 11 F-8s were shot down by MiGs.[21][22][23] A total of 170 F-8 Crusaders would be lost to all causes - mostly ground fire and accidents - during the war.[24][25]

%2C_in_the_early_1970s.jpg)

| Name | Squadron | Aircraft | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDR Harold L. Marr | VF-211 | MiG-17 | 12 June 1966 |

| LT Eugene J. Chancy | VF-211 | MiG-17 | 21 June 1966 |

| LTJG Philip V. Vampatella | VF-211 | MiG-17 | 21 June 1966 |

| CDR Richard M. Bellinger | VF-162 | MiG-21 | 9 October 1966 |

| CDR Marshall O. Wright | VF-211 | MiG-17 | 1 May 1967 |

| CDR Paul H. Speer | VF-211 | MiG-17 | 19 May 1967 |

| LTJG Joseph M. Shea | VF-211 | MiG-17 | 19 May 1967 |

| LCDR Bobby C. Lee | VF-24 | MiG-17 | 19 May 1967 |

| LT Phillip R. Wood | VF-24 | MiG-17 | 19 May 1967 |

| LCDR Marion H. Isaacks | VF-24 | MiG-17 | 21 July 1967 |

| LCDR Robert L. Kirkwood | VF-24 | MiG-17 | 21 July 1967 |

| LCDR Ray G. Hubbard, Jr. | VF-211 | MiG-17 | 21 July 1967 |

| LT Richard E. Wyman | VF-162 | MiG-17 | 14 December 1967 |

| CDR Lowell R. Myers | VF-51 | MiG-21 | 26 June 1968 |

| LCDR John B. Nichols | VF-191 | MiG-17 | 9 July 1968 |

| CDR Guy Cane | VF-53 | MiG-17 | 29 July 1968 |

| LT Norman K. McCoy, Jr. | VF-51 | MiG-21 | 1 August 1968 |

| LT Anthony J. Nargi | VF-111 | MiG-21 | 19 September 1968 |

| LT Gerald D. Tucker | VF-211 | MiG-17 pilot ejected before combat | 22 April 1972 |

End of service with U.S. Navy

LTV built and delivered the 1,219th (and last) U.S. Navy Crusader to VF-124 at NAS Miramar on 3 September 1964.[1]

The last active duty Navy Crusader fighter variants were retired from VF-191 and VF-194 aboard Oriskany in 1976 after almost two decades of service, setting a first for a Navy fighter.

The photo reconnaissance variant continued to serve in the active duty Navy for yet another 11 years, with VFP-63 flying RF-8Gs up to 1982, and with the Naval Reserve flying their RF-8Gs in two squadrons (VFP-206 and VFP-306) at Naval Air Facility Washington / Andrews AFB until the disestablishment of VFP-306 in 1984 and VFP-206 on 29 March 1987 when the last operational Crusader was turned over to the National Air and Space Museum.[26]

The F-8 Crusader is the only aircraft to have used the AIM-9C which is a radar-guided variant of the Sidewinder. When the Crusader retired, these missiles were converted to the AGM-122 Sidearm anti-radiation missiles used by United States attack helicopters against enemy radars.

NASA

Several modified F-8s were used by NASA in the early 1970s, proving the viability of both digital fly-by-wire technology (using data-processing equipment adapted from the Apollo Guidance Computer),[27] as well as supercritical wing design.[28]

French Navy

When the French Navy's air arm, the Aéronavale, required a carrier based fighter in the early 1960s to serve aboard the new carriers Clemenceau and Foch, the F-4 Phantom, then entering service with the United States Navy, proved to be too large for the small French ships. Following carrier trials aboard Clemenceau on 16 March 1962, by two VF-32 F-8s from the American carrier USS Saratoga, the Crusader was chosen and 42 F-8s were ordered, the last Crusaders produced.

The French Crusaders were based on the F-8E, but were modified in order to allow operations from the small French carriers, with the maximum angle of incidence of the aircraft's wing increased from five to seven degrees and blown flaps fitted. The aircraft's weapon system was modified to carry two French Matra R.530 radar or infra-red missiles as an alternative to Sidewinders, although the ability to carry the American missile was retained.[29] Deliveries of the new aircraft, dubbed the F-8E(FN), started in October 1964 and continued until February 1965, with the Aéronavale's first squadron, Flotille 12F reactivated on 1 October 1964.[29] To replace the old Corsairs, Flotille 14.F received its Crusaders on 1 March 1965.[30][31]

In October 1974, (on Clemenceau) and June 1977 (on Foch), Crusaders from 14.F squadron participated in the Saphir missions over Djibouti. On 7 May 1977, two Crusaders went separately on patrol against supposedly French Air Force (4/11 Jura squadron) F-100 Super Sabres stationed at Djibouti. The leader intercepted two fighters and engaged a dogfight (supposed to be a training exercise) but quickly called his wingman for help as he had actually engaged two Yemeni MiG-21s. The two French fighters switched their master armament to "on" but, ultimately, everyone returned to their bases. This was the only combat interception by French Crusaders.

The Aéronavale Crusaders flew combat missions over Lebanon in 1983 escorting Dassault-Breguet Super Étendard strike aircraft. In October 1984, France sent Foch for Operation Mirmillon off the coast of Libya, intended to calm Colonel Ghaddafi down, with 12.F squadron. The escalation of the situation in the Persian Gulf, due to the Iran-Iraq conflict, triggered the deployment of Clemenceau task force and its air wing, including 12.F squadron. 1993 saw the beginning of the missions over ex-Yugoslavia. Crusaders were launched from both carriers cruising in the Adriatic Sea. These missions ceased in June 1999 with Operation Trident over Kosovo.

The French Crusaders were subject to a series of modifications throughout their life, being fitted with new F-8J-type wings in 1969 and having modified afterburners fitted in 1979.[32] Armament was enhanced by the addition of R550 Magic infra-red guided missiles in 1973, with the improved, all-aspect Magic 2 fitted from 1988. The obsolete R.530 was withdrawn from use in 1989, leaving the Crusaders without a radar-guided missile.[33] In 1989, when it was realised that the Crusader would not be replaced for several years due to delays in the development of the Rafale, it was decided to refurbish the Crusaders to extend their operating life. Each aircraft was rewired and had its hydraulic system refurbished, while the airframe was strengthened to extend fatigue life. Avionics were improved, with a modified navigation suite and a new radar-warning receiver.[34][35] The 17 refurbished aircraft were redesignated as F-8P (P used for "Prolongé" -extended- and not to be confused with the Philippine F-8P).[36] Although the French Navy participated in combat operations in 1991 during Operation Desert Storm and over Kosovo in 1999, the Crusaders stayed behind and were eventually replaced by the Rafale M in 2000 as the last of the type in military service.

Philippine Air Force

In late 1977, the Philippine government purchased 35 secondhand U.S. Navy F-8Hs that were stored at Davis-Monthan AFB in Arizona.[37] Twenty-five of them were refurbished by Vought and the remaining 10 were used for spare parts.[37] As part of the deal, the U.S. would train Philippine pilots using the TF-8A.[37] The Crusaders were manned by the 7th Tactical Fighter Squadron at Basa Air Base and were mostly used for intercepting Soviet bombers.[37] But due to lack of spares and the rapid deterioration of the aircraft, the remaining F-8s were grounded in 1988 and left on an open grass field at Basa Air Base. They were finally withdrawn from service in 1991 after they were badly damaged by the Mount Pinatubo eruption, and have since been offered for sale as scrap.

Variants

- XF8U-1 (XF-8A) (V-383) – the two original unarmed prototypes.

- F8U-1 (F-8A) – first production version, J57-P-12 engine replaced with more powerful J57-P-4A starting with 31st production aircraft, 318 built.

- YF8U-1 (YF-8A) – one F8U-1 fighter used for development testing.

- YF8U-1E (YF-8B) – one F8U-1 converted to serve as an F8U-1E prototype.

- F8U-1E (F-8B) – added a limited all-weather capability thanks to the AN/APS-67 radar, the unguided rocket tray was sealed shut because it was never used operationally, first flight: 3 September 1958, 130 built.

- XF8U-1T – one XF8U-2NE used for evaluation as a two-seat trainer.

- F8U-1T (TF-8A) (V-408) – two-seat trainer version based on F8U-2NE, fuselage stretched 2 ft (0.61 m), internal armament reduced to two cannon, J57-P-20 engine, first flight 6 February 1962. The Royal Navy was initially interested in the Rolls-Royce Spey-powered version of TF-8A but chose the Phantom II instead. Only one TF-8A was built, although several retired F-8As were converted to similar two-seat trainers.

- YF8U-2 (YF-8C) – two F8U-1s used for flight testing the J57-P-16 turbojet engine.

- F8U-2 (F-8C) – J57-P-16 engine with 16,900 lbf (75 kN) of afterburning thrust, ventral fins added under the rear fuselage in an attempt to rectify yaw instability, Y-shaped cheek pylons allowing two Sidewinder missiles on each side of the fuselage, AN/APQ-83 radar retrofitted during later upgrades. First flight: 20 August 1957, 187 built. This variant was sometimes referred to as Crusader II.[38]

- F8U-2N (F-8D) – all-weather version, unguided rocket pack replaced with an additional fuel tank, J57-P-20 engine with 18,000 lbf (80 kN) of afterburning thrust, landing system which automatically maintained present airspeed during approach, incorporation of AN/APQ-83 radar. First flight: 16 February 1960, 152 built.

- YF8U-2N (YF-8D) – one aircraft used in the development of the F8U-2N.

- YF8U-2NE – one F8U-1 converted to serve as an F8U-2NE prototype.

- F8U-2NE (F-8E) – J57-P-20A engine, AN/APQ-94 radar in a larger nose cone, dorsal hump between the wings containing electronics for the AGM-12 Bullpup missile, payload increased to 5,000 lb (2,270 kg), Martin-Baker ejection seat, AN/APQ-94 radar replaced AN/APQ-83 radar in earlier F-8D. IRST sensor blister (round ball) was added in front of the canopy.[39] First flight: 30 June 1961, 286 built.

- F-8E(FN) – air superiority fighter version for the French Navy, significantly increased wing lift due to greater slat and flap deflection and the addition of a boundary layer control system, enlarged stabilators, incorporated AN/APQ-104 radar, an upgraded version of AN/APQ-94. A total of 42 built.

- F-8H – upgraded F-8D with strengthened airframe and landing gear, with AN/APQ-84 radar. A total of 89 rebuilt.

- F-8J – upgraded F-8E, similar to F-8D but with wing modifications and BLC like on F-8E(FN), "wet" pylons for external fuel tanks, J57-P-20A engine, with AN/APQ-124 radar. A total of 136 rebuilt.

- F-8K – upgraded F-8C with Bullpup capability and J57-P-20A engines, with AN/APQ-125 radar. A total of 87 rebuilt.

- F-8L – F-8B upgraded with underwing hardpoints, with AN/APQ-149 radar. A total of 61 rebuilt.

- F-8P – 17 F-8E(FN) of the Aéronavale underwent a significant overhaul at the end of the 1980s to stretch their service life another 10 years. They were retired in 1999.[40]

- F8U-1D (DF-8A) – several retired F-8A modified to controller aircraft for testing of the SSM-N-8 Regulus cruise missile. DF-8A was also modified as drone (F-9 Cougar) control which were used extensively by VC-8, NS Roosevelt Rds, PR; Atlantic Fleet Missile Range.

- DF-8F – retired F-8A modified as controller aircraft for testing of missiles including at the USN facility at China Lake.

- F8U-1KU (QF-8A) – retired F-8A modified into remote-controlled target drones

- YF8U-1P (YRF-8A) – prototypes used in the development of the F8U-1P photo-reconnaissance aircraft – V-392.

- F8U-1P (RF-8A) – unarmed photo-reconnaissance version of F8U-1E, 144 built.

- RF-8G – modernized RF-8As.

- LTV V-100 – revised "low-cost" development based on the earlier F-8 variants, created in 1970 to compete against the F-4E Phantom II, Lockheed CL-1200 and F-5-21 in a tender for U.S. Military Assistance Program (MAP) funding. The unsuccessful design was ultimately only a "paper exercise."[41]

- XF8U-3 Crusader III (V-401) – new design loosely based on the earlier F-8 variants, created to compete against the F-4 Phantom II; J75-P-5A engine with 29,500 lbf (131 kN) of afterburning thrust, first flight: 2 June 1958, attained Mach 2.39 in test flights, canceled after five aircraft were constructed because the Phantom II won the Navy contract.

Aircraft on display

France

- F-8E(FN)

- 151732 (French Navy Side Number 1) – Musee des Avions de Chasse, Beaune.[42]

- 151750 (French Navy Side Number 19) – Musée des Ailes Anciennes, Toulouse.[43]

- F-8P

.jpg)

- 151733 (French Navy Side Number 3) – Lann Bihoue Airport, Le Meneguen.[44]

- 151735 (French Navy Side Number 4) – Musee Europeen de lAviation de Chasse, Montelimar-Ancone.[45]

- 151738 (French Navy Side Number 7) – Aeronavale Base, Landivisau.[46]

- 151741 (French Navy Side Number 10) – Musee de l air et de l Espace, (The Air and Space Museum), Paris, France.[47]

- 151742 (French Navy Side Number 11) – Musee de l aeronautique navale, Rochefort.[48]

- 151754 (French Navy Side Number 23) – Aeronavale Base, Landivisau.[49]

- 151760 (French Navy Side Number 29) – Aeronavale Base, Landivisau.[50]

- 151767 (French Navy Side Number 36) – Musee des Avions de Chasse, Beaune.[51]

- 151768 (French Navy Side Number 37) – Airport in Cuers.[52]

- 151770 (French Navy Side Number 39) – Aeronavale Base, Landivisau.[53]

Philippines

- F-8H

- 147056 – Philippine Air Force Aerospace Museum, Villamor Air Base, Manila.[54]

- 147060 - Basa Air Base, Floridablanca, Pampanga.

- 148661 – Clark Air Base, Angeles.[55]

- 148696 - Fort Del Pilar, Baguio.

United States

%2C_on_16_June_2016.png)

- XF8U-1 (XF-8A)

- 138899 – Museum of Flight in Seattle, Washington.[56]

- XF8U-2 (XF-8C)

- F8U-1 (F-8A)

- 141351 – NAS Jacksonville Heritage Park, Naval Air Station Jacksonville, Florida (relocated from former NAS Cecil Field).[58]

- 141353 – Edwards AFB, California.[59]

- 143703 – USS Hornet Museum, former Naval Air Station Alameda, Alameda, California.[60]

- 143755 – Marine Corps Air Station Miramar, California.[61]

- 143806 – Wings of Freedom Aviation Museum, former Naval Air Station Willow Grove, Willow Grove, Pennsylvania.[62]

- 144427 – Pima Air and Space Museum adjacent to Davis-Monthan AFB in Tucson, Arizona.[63]

- 145336 – Planes of Fame at Chino, California.[64]

- 145347 – National Naval Aviation Museum at Naval Air Station Pensacola, Florida.[65]

- 145349 – Pueblo Weisbrod Aircraft Museum, Pueblo, Colorado.[66]

- 145397 – Naval Air Engineering Station Lakehurst, Lakehurst, New Jersey.[67]

- F8U-2 (F-8C)

- 145527 - under restoration to airworthiness by a private owner in Seattle, Washington,[68]

- 145546 – Edwards AFB, California.[69]

- 145592 - under restoration to airworthiness by a private owner in Seattle, Washington,[70]

- 146963 – Marine Corps Air Station Beaufort, South Carolina.[71]

- 146973 – Marine Corps Air Station Kaneohe Bay, Hawaii[72]

- 147034 – (nose section only) USS Hornet Museum, former NAS Alameda, Alameda, California.[73]

- 149150 – NAS Oceana Aviation Heritage Park, Naval Air Station Oceana, Virginia.[74]

- F8U-2N (F-8D)

- 148693 – Mid America Air Museum in Liberal, Kansas.[75]

F8U-2NE (F-8E)

F-8E(FN)

- 151765 – under restoration to airworthiness by a private owner in Fort Myers, Florida[77]

- F8U-1P (RF-8G)

- 144617 – Flying Leatherneck Aviation Museum at Marine Corps Air Station Miramar, California[78]

- 144618 – Celebrity Row, Davis-Monthan AFB (North Side), Tucson, Arizona.[79]

- 145607 – Castle Air Museum (former Castle AFB), Atwater, California.[80]

- 145608 – (nose section only) Pacific Coast Air Museum, Santa Rosa, California.[81]

- 145609 – National Museum of Naval Aviation, Naval Air Station Pensacola, Pensacola, Florida.[82]

- 145645 – USS Alabama Battleship Memorial Park, Mobile, Alabama.[83]

- 146860 – Smithsonian Institution's National Air and Space Museum Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia, adjacent to Dulles International Airport.[84]

- 146858 – in storage at Flying Leatherneck Aviation Museum at Marine Corps Air Station Miramar, California[76]

- 146882 – Frontiers of Flight Museum in Dallas, Texas.[85]

- 146898 – Fort Worth Aviation Museum in Fort Worth, Texas.[86]

- F-8H

- 147909 – NAD Soroptimist Park, Kitsap Lake, Bremerton, Washington, about 1 mile away from Naval Hospital Bremerton. Aircraft is on loan from the National Naval Aviation Museum, Pensacola, Florida.[87]

- F-8J

.jpg)

- 150904 – Air Zoo in Kalamazoo, Michigan.[88]

- F8U-2 (F-8K)

- 145550 – USS Intrepid Museum in New York City, New York.[89]

- 146931 – Estrella Warbirds Museum in Paso Robles, California.[90]

- 146939 – Patriots Point Naval & Maritime Museum aboard ex-USS Yorktown (CV-10), Mount Pleasant, South Carolina.[91]

- 146983 – Marine Corps Air Station Kaneohe Bay, Hawaii.[92]

- 146985 – Valiant Air Command Warbird Museum at Space Coast Regional Airport in Titusville, Florida[93]

- 146995 – Pacific Coast Air Museum, adjacent to the Sonoma County Airport in Santa Rosa, California[94]

- 147030 – USS Midway Museum in San Diego, California.[95]

- F-8L

- 145449 – Naval Air Station Fallon, Fallon, Nevada.[96]

- F8U Cockpit

- 145399 – Under restoration at Moffett Historical Museum, Moffett Federal Airfield, California

Specifications (F-8E)

Data from The Great Book of Fighters[97] and Quest for Performance[98] Combat Aircraft since 1945[99] Joseph F. Baugher [100]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 54 ft 3 in (16.54 m)

- Wingspan: 35 ft 8 in (10.87 m)

- Height: 15 ft 9 in (4.80 m)

- Wing area: 375 sq ft (34.8 m2)

- Aspect ratio: 3.4

- Airfoil: root: NACA 65A006 mod; tip: NACA 65A005 mod

- Zero-lift drag coefficient: CD0.0133

- Drag area: 5.0 sq ft (0.46 m2)

- Empty weight: 17,541 lb (7,956 kg)

- Gross weight: 29,000 lb (13,154 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 34,000 lb (15,422 kg)

- Fuel capacity: 1,325 US gal (1,103.3 imp gal; 5,015.7 L)

- Powerplant: 1 × Pratt & Whitney J57-P-20A afterburning turbojet engine, 10,700 lbf (48 kN) thrust dry, 18,000 lbf (80 kN) with afterburner

Performance

- Maximum speed: 1,066 kn (1,227 mph, 1,974 km/h) at 36,000 ft (10,973 m)

- Maximum speed: Mach 1.86

- Cruise speed: 495 kn (570 mph, 917 km/h)

- Combat range: 394 nmi (453 mi, 730 km)

- Ferry range: 1,507 nmi (1,734 mi, 2,791 km) with external fuel

- Service ceiling: 58,000 ft (18,000 m)

- Rate of climb: 19,000 ft/min (97 m/s) [101]

- Lift-to-drag: 12.8

- Wing loading: 77.3 lb/sq ft (377 kg/m2)

- Thrust/weight: 0.62

Armament

- Guns: 4× 20 mm (0.79 in) Colt Mk 12 cannons in lower fuselage, 125 rpg

- Hardpoints: 2× side fuselage mounted Y-pylons (for mounting AIM-9 Sidewinders and Zuni rockets) and 2× underwing pylon stations with a capacity of 4,000 lb (2,000 kg),with provisions to carry combinations of:

- Rockets: 2× LAU-10 rocket pods (each with 4× 5 inch (127mm) Zuni rockets)

- Missiles:

- 4× AIM-9 Sidewinder or Matra Magic (French Navy only) air-to-air missiles

- 2× AGM-12 Bullpup air-to-surface missiles

- Bombs:

- 12× 250 lb (113 kg) Mark 81 bombs or

- 8× 500 lb (227 kg) Mark 82 bombs or

- 4× 1,000 lb (454 kg) Mark 83 bombs or

- 2× 2,000 lb (907 kg) Mark 84 bombs

Avionics

Magnavox AN/APQ-84 or AN/APQ-94 Fire-control radar

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

Related lists

References

Notes

- United States Naval Institute Proceedings, January 1965, p. 136.

- Michel 2007, p. 11.

- Tillman 1990

- Goebel, Greg. "The Vought F-8 Crusader." Air Vectors. Retrieved: 7 March 2006. Archived May 17, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Bjorkman, Eileen, Gunfighters, Air & Space, November 2015, p.61

- Bjorkman, Eileen, Gunfighters, Air & Space, November 2015, p.62

- Weaver, F-8 Crusader, p. 65.

- "Records." Archived 2007-02-09 at the Wayback Machine cloudnet.com. Retrieved: 28 December 2009.

- Glenn and Taylor 2000, p. 231.

- Cosby, Samuel. "Cuban crisis era jet at Open Cockpit Day in Atwater". Archived 2011-08-24 at the Wayback Machine Modesto Bee, 27 May 2011. Retrieved: 1 August 2011.

- Mersky 1986, p. 25.

- Mersky 1986, pp. 25–26.

- Mersky, 1998, p. back, side and table in Appendix B.

- "U.S. Navy's transition to jets." Archived 2012-09-13 at the Wayback Machine usnwc.edu. Retrieved: 23 July 2012.

- Anderton 1987, p. 71.

- Toperczer 2001, pp. 26, 28, 29, 88.

- Hobson p. 17

- Grossnick and Armstrong 1997

- "Crusader In Action." faqs.org. Retrieved: 28 December 2009.

- Michel 2007, p. 51,

- Hobson p. 271

- "Vietnamese Air-to-Air Victories, Part 1." Acig.org. Retrieved: 7 March 2011.

- "Vietnamese Air-to-Air Victories, Part 2." Acig.org. Retrieved: 7 March 2011.

- Hobson 2001, pp. 269–270.

- "The Last Gunfighter". www.crusader.gaetanmarie.com.

- Baugher, Joe. "Crusader in Navy/Marine Corps Service." F8 Crusader: US Navy Fighter Aircraft, 6 August 2003. Retrieved: 11 June 2011.

- Witt, Stephen (June 24, 2019). "Apollo 11: Mission Out of Control". Wired. San Francisco: Condé Nast Publications. Retrieved September 18, 2019.

- NASA F-8 www.nasa.gov. Retrieved 3 June 2010

- Stijger Air International October 1993, p. 192.

- Stijger Air International October 1993, pp. 192–193.

- Rochotte, Léon C., Ramon Josa and Alexandre Gannier. "Capitaine de Frégate (H): Les Corsair français". NetMarine.net, 1999. Retrieved: 14 July 2009.

- Stijgers Air International October 1993, p. 195.

- Stijgers Air International October 1993, p. 194.

- Stijgers Air International October 1993, pp. 195–196.

- Michell 1993, p. 58.

- Mersky Wings of Fame 1996, p. 83.

- "F-8 Crusader". Milavia.

- Pike, J. "F8U-3 Crusader III." GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved: 9 July 2009.

- "Chance Vought/LTV History" Retrieved: 30 JULY 2013.

- Winchester 2006, p. 242.

- "Low-Cost US Fighter." Air Pictorial, Volume 32, No. 3, March 1970.

- "F8U Crusader/151732." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 June 2015.

- "F8U Crusader/151750." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 June 2015.

- "F8U Crusader/151733." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 June 2015.

- "F8U Crusader/151735." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 June 2015.

- "F8U Crusader/151738." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 June 2015.

- "F8U Crusader/151741." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 June 2015.

- "Le musée". www.anaman.fr.

- "F8U Crusader/151754." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 June 2015.

- "F8U Crusader/151760." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 June 2015.

- "F8U Crusader/151767." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 June 2015.

- "F8U Crusader/151768." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 June 2015.

- "F8U Crusader/151770." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 June 2015.

- "F8U Crusader/147056." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 June 2015.

- "F8U Crusader/148661." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 June 2015.

- "XF8U Crusader/138899." Museum of Flight. Retrieved: 26 October 2012.

- "XF8U Crusader/140448." McAuliffe-Shepard Discovery Center. Retrieved: 26 October 2012.

- "F8U Crusader/141351." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 June 2015.

- "F8U Crusader/141353." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 June 2015.

- "F8U Crusader/143703." Archived 2012-10-29 at the Wayback Machine USS Hornet Museum. Retrieved: 26 October 2012.

- "F8U Crusader/143755." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 26 October 2012.

- "F8U Crusader/143806." Wings of Freedom Aviation Museum. Retrieved: 22 January 2015.

- "F8U Crusader/144427." Pima Air and Space Museum. Retrieved: 23 June 2015.

- "F8U Crusader/145336." Archived 2017-08-06 at the Wayback Machine Planes of Fame. Retrieved: 07 October 2013.

- "F8U Crusader/145347." National Naval Aviation Museum. Retrieved: 22 January 2015.

- "F8U Crusader/145349." Archived 2016-12-25 at the Wayback Machine Pueblo Weisbrod Aircraft Museum. Retrieved: 23 June 2015.

- "F8U Crusader/145397." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 June 2015.

- "FAA Registry: N37TB faa.gov Retrieved: 22 October 2018.

- "F8U Crusader/145546." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 June 2015.

- "FAA Registry: N19TB faa.gov Retrieved: 22 October 2018.

- "F8U Crusader/146963." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 June 2015.

- "F8U Crusader/146973." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 June 2015.

- "F8U Crusader/147034." Archived 2015-06-23 at the Wayback Machine USS Hornet Museum. Retrieved: 23 June 2015.

- "F8U Crusader/149150." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 June 2015.

- "F8U Crusader/148693." Mid America Air Museum. Retrieved: 23 June 2015.

- "F8U Crusader/150920" Flying Leatherneck Aviation Museum and Historical Foundation. Retrieved: 22 January 2015.

- "FAA Registry: N3512Z" faa.gov. Retrieved: 22 October 2018.

- "F8U Crusader/144617" Flying Leatherneck Aviation Museum and Historical Foundation. Retrieved: 22 January 2015.

- [Celebrity Row, Davis-Monthan AFB (North Side), Tucson, Arizona "F8U Crusader/144618."] aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 June 2015.

- "F8U Crusader/145607." Archived 2014-07-07 at the Wayback Machine Castle Air Museum. Retrieved: 23 June 2015.

- "F8U Crusader/145608." Pacific Coast Air Museum. Retrieved: 23 June 2015.

- "F8U Crusader/145609." National Naval Aviation Museum. Retrieved: 23 June 2015.

- "F8U Crusader/145645." Archived 2015-12-18 at the Wayback Machine USS Battleship Alabama Memorial Park. Retrieved: 23 June 2015.

- "F8U Crusader/146860." NASM. Retrieved: 26 October 2012.

- "F8U Crusader/146882." Archived 2013-10-17 at the Wayback Machine Frontiers of Flight Museum. Retrieved: 26 October 2012.

- "F8U Crusader/146898." Fort Worth Aviation Museum. Retrieved: 22 January 2015.

- "F8U Crusader/147909." Aerial Visuals. Retrieved: 27 February 2013.

- "F8U Crusader/150904." Air Zoo. Retrieved: 26 October 2012.

- "F8U Crusader/145550." USS Intrepid Museum. Retrieved: 22 January 2015.

- "F8U Crusader/146931." Estrella Warbirds Museum. Retrieved: 20 April 2013.

- "F8U Crusader/146939." Patriots Point Naval & Maritime Museum. Retrieved: 26 October 2012.

- "F8U Crusader/146983." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 June 2015.

- "F8U Crusader/146985." Archived 2015-01-13 at the Wayback Machine Valiant Air Command Warbird Museum. Retrieved: 22 January 2015.

- "F8U Crusader/146995." Pacific Coast Air Museum. Retrieved: 1 May 2012.

- "F8U Crusader/147030." USS Midway Museum. Retrieved: 26 October 2012.

- "F8U Crusader/145449." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 June 2015.

- Green, William and Gordon Swanborough. The Great Book of Fighters. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing. 2001. ISBN 0-7603-1194-3.

- Loftin, L.K. Jr. "Quest for Performance: The Evolution of Modern Aircraft, NASA SP-468." NASA. Retrieved: 22 April 2006.

- Wilson 2000, p. 141.

- Baugher, Joe. "Vought F8U-2NE (F-8E) Crusader". joebaugher.com. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- "Vought F-8 Crusader Carrier-Borne Naval Fighter Aicraft [sic]". militaryfactory.com.

Bibliography

- Anderton, David A. North American F-100 Super Sabre. London: Osprey Publishing Limited, 1987. ISBN 0-85045-662-2.

- Glenn, John and Nick Taylor. John Glenn: A Memoir. New York: Bantam, 2000. ISBN 0-553-58157-0.

- Grant, Zalin. Over the Beach: The Air War in Vietnam. New York: Pocket Books, 1988. ISBN 978-0-393-32727-4.

- Grossnick, Roy A. and William J. Armstrong. United States Naval Aviation, 1910–1995. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Historical Center, 1997. ISBN 0-16-049124-X.

- Hobson, Chris. Vietnam Air Losses, USAF, USN, USMC, Fixed-Wing Aircraft Losses In Southeast Asia 1961–1973. North Branch, Minnesota: Specialty Press, 2001. ISBN 1-85780-115-6.

- McCarthy, Donald J., Jr. MiG Killers, A Chronology of U.S. Air Victories in Vietnam 1965–1973. North Branch, Minnesota: Specialty Press, 2009. ISBN 978-1-58007-136-9.

- Mersky, Peter. F-8 Crusader Units of the Vietnam War (Osprey Combat Aircraft #7). Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing Limited, 1998. ISBN 978-1-85532-724-5.

- Mersky, Peter. RF-8 Crusader Units over Cuba and Vietnam (Osprey Combat Aircraft #12). Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing Limited, 1999. ISBN 978-1-85532-782-5.

- Mersky, Peter B. Vought F-8 Crusader (Osprey Air Combat). Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing Limited, 1986. ISBN 0-85045-905-2.

- Mersky, Peter B. Vought F-8 Crusader: MiG-Master. Wings of Fame, Volume 5, 1996, pp. 32–95. London: Aerospace Publishing. ISBN 1-874023-90-5. ISSN 1361-2034.

- Michel III, Marshall L. Clashes: Air Combat Over North Vietnam 1965–1972. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 2007, First edition 1997. ISBN 1-59114-519-8.

- Moise, Edwin E. Tonkin Gulf and the Escalation of the Vietnam War. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press, 1996. ISBN 0-8078-2300-7.

- Stijger, Eric. Aéronavale Crusaders. Air International, Vol. 45, No. 4, October 1993, pp. 192–196. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Tillman, Barrett. MiG Master: Story of the F-8 Crusader (second edition). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1990. ISBN 0-87021-585-X.

- Toperczer, István. MiG-17 And MiG-19 Units of the Vietnam War (Osprey Combat Aircraft #25). Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing Limited, 2001. ISBN 1-84176-162-1.

- Weaver, Michael E. "An Examination of the F-8 Crusader through Archival Sources." Journal of Aeronautical History, 2018. https://www.aerosociety.com/media/8037/an-examination-of-the-f-8-crusader-through-archival-sources.pdf

- Wilson, Stewart. Combat Aircraft since 1945. Fyshwick, Australia: Aerospace Publications, 2000. ISBN 1-875671-50-1.

- Winchester, Jim, ed. Vought F-8 Crusader. Military Aircraft of the Cold War (The Aviation Factfile). London: Grange Books plc, 2006. ISBN 1-84013-929-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vought F-8 Crusader. |