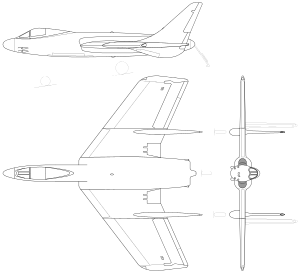

Vought F7U Cutlass

The Vought F7U Cutlass was a United States Navy carrier-based jet fighter and fighter-bomber of the early Cold War era. It was a tailless aircraft for which aerodynamic data from projects of the German Arado and Messerschmitt companies, obtained at the end of World War II through German scientists who worked on the projects, contributed; though Vought designers denied any link to the German research at the time.[1] The F7U was the last aircraft designed by Rex Beisel, who was responsible for the first fighter ever designed specifically for the U.S. Navy, the Curtiss TS-1 of 1922.

| F7U Cutlass | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| circa 1955 | |

| Role | Naval multirole fighter |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Chance Vought |

| First flight | 29 September 1948 |

| Introduction | July 1951 |

| Retired | 2 March 1959 |

| Primary user | United States Navy |

| Produced | 1948–1955 |

| Number built | 320 |

Regarded as a radical departure from traditional aircraft design, the Cutlass suffered from numerous technical and handling problems throughout its short service career. The type was responsible for the deaths of four test pilots and 21 other U.S. Navy pilots.[1] Over one quarter of all Cutlasses built were destroyed in accidents.[2]

Design and development

The Cutlass was Vought's entry to a U.S. Navy competition for a new carrier-capable day fighter, opened on 1 June 1945. Former Messerschmitt AG senior designer Waldemar Voigt, who supervised the development of numerous experimental jet fighters in Nazi Germany, contributed to its design with his experience in the development of the Messerschmitt P.1110 and P.1112 projects.[3][4] The requirements were for an aircraft that was able to fly at 600 miles per hour (970 km/h) at 40,000 feet (12,000 m).[1]

The design featured broad chord, low aspect ratio swept wings, with twin wing-mounted tail fins either side of a short fuselage. The cockpit was situated well forward to provide good visibility for the pilot during aircraft carrier approaches. The design was given the company type number of V-346 and then the official designation of "F7U" when it was announced the winner of the competition.[1]

Pitch and roll control was provided by elevons, though Vought called these surfaces "ailevators" at the time. Slats were fitted to the entire span of the leading edge. All controls were hydraulically-powered.

The very long nose landing gear strut required for high angle of attack takeoffs lifted the pilot 14 feet into the air and was fully steerable.[2] The high stresses of barrier engagements, and side-loads imposed during early deployment carrier landings caused failure of the retract cylinder's internal down-locks, causing nose gear failure and resultant spinal injuries to the pilot.[5]

The aircraft had all-hydraulic controls which provided artificial feedback so the pilot could feel aerodynamic forces acting on the plane. The hydraulic system operated at 3000 psi, twice that of other Navy aircraft. The hydraulic system was not ready for front-line service and was unreliable.[2]

The F7U was underpowered by its Westinghouse J34 turbojets, an engine that some pilots liked to say "put out less heat than Westinghouse's toasters." Naval aviators called the F7U the "Gutless Cutlass" and/or the "Ensign Eliminator" or, in kinder moments, the "Praying Mantis".[5]

Testing

None of the 14 F7U-1s built between 1950 and 1952 became approved to be used in squadron service.[2]

On 7 July 1950 Vought test pilot Paul Thayer ejected from his burning prototype in front of an airshow crowd.[2]

On 20 December 1951, the F7U-3 version took off for its maiden flight. The F7U-3 featured other engines, a stronger airframe larger by a third and extra maintenance panel for service access.[2]

Test pilot and later astronaut Walter Schirra wrote in his autobiography that he considered the F7U-3 accident prone and a "widow maker". On the positive side, test pilots found it a stable weapons platform, maneuverable, fun to fly and the strengthened airframe to be sturdy. Test pilots particularly praised its high roll rate at 570 degrees/s, three times faster than most production jets at the time.[2]

Flight characteristics

The Cutlass would gyrate after a stall. When Lt. Morrey Loso found himself tumbling about in the cockpit in his tumbling aircraft after a stall, he found that when he let go of the control stick to reach with both hands for the ejection handle, the Cutlass self-corrected. This meant that normal recovery procedures did not apply to the Cutlass and the result was later confirmed in wind-tunnel testing.[2]

Operational history

Three prototypes were ordered in 1946, with the first example flying on 29 September 1948, piloted by Vought's chief test pilot, J. Robert Baker. The maiden flight took place from Naval Air Station Patuxent River in Maryland,[6][7] and was not without its problems. During testing one of the prototypes reached a maximum speed of 625 mph (1,058 km/h).[8]

Production orders were placed for the F7U-1 in a specification very close to the prototypes, and further developed F7U-2 and F7U-3 versions with more powerful engines. Because of development problems with the powerplant, however, the F7U-2 would never be built, while the F7U-3 would incorporate many refinements suggested by tests of the -1. The first 16 F7U-3s had non-afterburning Allison J35-A-29 engines. The -3, with its Westinghouse J46-WE-8B turbojets, would eventually become the definitive production version, with 288 aircraft equipping 13 U.S. Navy squadrons. Further development stopped once the Vought F8U Crusader flew.

The F7U's performance suffered due to a lack of sufficient engine thrust; consequently, its carrier landing and takeoff performance was notoriously poor. The J35 was known to flame out in rain, a very serious fault.

The first fleet squadron to receive F7Us was Fighter Squadron 81 (VF-81) in April 1954. Few squadrons made deployments with the type, and most "beached" them ashore during part of the cruise owing to operating difficulties. Those units known to have taken the type to sea were:

- VF-124, USS Hancock, August 1955 – March 1956. After pilot George Millard was killed in a Cutlass landing accident, the captain ordered every Cutlass off the ship and the squadron spent its Pacific cruise at the Atsugi naval air station in Japan.[2]

- VF-81, USS Ticonderoga, November 1955 – August 1956; after a pilot was injured after a nosegear collapse, the squadron was ordered ashore at Naval Air Station Port Lyautey.[2]

- VA-86, USS Forrestal, January – March 1956 shakedown cruise;

- VA-83, USS Intrepid, March – September 1956;

- VA-116, USS Hancock, April - September 1957;

- VA-151, USS Lexington, May - December 1956;

- VA-212, USS Bon Homme Richard, August 1956 – February 1957.

- Air Test and Evaluation Squadron 4 (VX-4), USS Shangri-La and USS Lexington

In 1957, Chance Vought analysed the accident record and found that with 78 accidents and a quarter of the airframes lost in 55,000 flight hours, the Cutlass had the highest accident rate of all Navy swept-wing fighters.[2]

The poor safety record meant that Vice Admiral Harold M. “Beauty” Martin, air commander of the United States Pacific Fleet replaced his Cutlass aircraft with Grumman F9F-8 Cougars.[2]

Blue Angels

The Navy Flight Demonstration Squadron, the Blue Angels, flew two F7U-1 Cutlasses (BuNos 124426 & 124427) as a side demonstration during their 1953 show season in an effort to promote the new aircraft, but did not use them as part of their regular formation demonstration. Both the pilots and ground crews found the aircraft generally unsatisfactory, and it was apparent that the type was still experiencing multiple teething troubles.[8] Among the failures were landing gear failures, hydraulic failures, engine fires while in the air and on one occasion a landing gear door fell on a spectator grandstand but through sheer luck did not injure anyone.[2]

During the Blue Angels' first airshow appearance in 1953, pilot Lt Edward "Whitey" Feightner, the former program manager for the F7U, experienced a total loss of hydraulics on a full afterburner takeoff and steep climb. While trying to gain enough altitude for ejection he was able to stay with the aircraft until the backup system came on. He clipped trees on the end of the runway, causing the left engine to flame out. With hydraulic fluid streaming back in a bright flame, he made a hard turn and got the plane back on the runway, much to the excitement of the crowd. Later, while traveling to an airshow at Naval Air Station Glenview in Chicago, Illinois, another Blue Angel pilot, Lt Harding MacKnight, experienced an engine flameout in his Cutlass, forcing him to make an emergency landing at NAS Glenview. Traveling with him, Feightner was redirected to make his landing at Chicago's former Orchard Airpark, which had been expanded and renamed O'Hare Airport. The runway had just been completed and was covered with peach baskets to prevent aircraft from landing until it was opened. Feightner was told to ignore the baskets and land on the new runway. As a result, Feightner's F7U became the first aircraft to land on the new runway for Chicago's O'Hare International Airport.

Following these incidents, the two Cutlasses were deemed unsuitable for demonstration flying and were flown to Naval Air Station Memphis, Tennessee, where they were abandoned to become aircraft maintenance instructional airframes for the Naval Technical Training Center.[9]

Variants

- XF7U-1

- Three prototypes ordered on 25 June 1946 (BuNos 122472, 122473 & 122474). First flight, 29 September 1948, all three aircraft were destroyed in crashes.[10]

- F7U-1

- The initial production version, 14 built. Powered by two J34-WE-32 engines.

- F7U-2

- Proposed version, planned to be powered by two Westinghouse J34-WE-42 engines with afterburner, but the order for 88 aircraft was cancelled.

- XF7U-3

- Designation given to one aircraft built as the prototype for the F7U-3, BuNo 128451. First flight: 20 December 1951.

- F7U-3

- The definitive production version, 180 built. Powered by two Westinghouse J46-WE-8B turbojets. The first sixteen aircraft, including the prototype, were powered by interim J35-A-29 non-afterburning engines.

- F7U-3P

- Photo-reconnaissance version, 12 built. With a 25 in longer nose and equipped with photo flash cartridges none of these aircraft saw operational service, being used only for research and evaluation purposes.[10]

- F7U-3M

- This missile capable version was armed with four AAM-N-2 Sparrow I air-to-air beam-riding missiles. 98 built of which 48 F7U-3 airframes under construction were upgraded to F7U-3M standard. An order for 202 additional aircraft was cancelled.

- A2U-1

- Designation given to a cancelled order of 250 aircraft to be used in the ground attack role.

Operators

- United States Navy

- VC-3

- VX-3

- VX-4

- VX-5

- VA-12

- VA-34

- VF-81/VA-66

- VF-83/VA-83

- VA-86

- VA-116

- VF-122

- VF-124

- VA-126

- VF-151/VA-151

- VF-212/VA-212

Accidents and incidents

- 26 July 1954 pilot Lt Floyd Nugent ejected from a Cutlass armed with 2.75 in rockets. The Cutlass continued to fly on and proceeded to circle the North Island of San Diego with its Hotel Del Coronado for 30 minutes, before it finally crashed close to shore.[2]

- 11 December 1954 during an air demonstration at the christening of aircraft carrier USS Forrestal, pilot Lt J.W. Hood was killed when his F7U-3 had a malfunction with the wing locking mechanism and the aircraft crashed into the sea.[2]

- 30 May 1955 pilot Lt Cmdr Paul Harwell's Cutlass suffered an engine fire upon takeoff on his first flight in the aircraft. Harwell ejected and never flew another Cutlass again. By the time he had landed on the ground, he had spent more airborne time in the parachute than the aircraft.[2]

- When pilot Tom Quillin's Cutlass took off as part of a flight of four Cutlasses. Quillin's aircraft had an electrical failure which forced him to abort his training mission and return to base. At the airbase he had to wait in a landing pattern because two other aircraft in the flight also had aborted due to malfunctions in the aircraft.[2]

- 14 July 1955 pilot LCDR Jay T. Alkire was killed in a ramp strike on USS Hancock.[11]

- 4 November 1955, pilot Lt George Millard was killed when his Cutlass went into the cable barrier at the end of the flight deck landing area of USS Hancock. The nosegear malfunctioned and drove a strut into the cockpit which triggered the ejection seat and dislodged the canopy. Millard was launched 200 feet (61 m) forward and hit the tail of a parked A-1 Skyraider and later died of his injuries. The captain of Hancock ordered every Cutlass off the ship.[2]

Aircraft on display

Seven F7U-3 Cutlass aircraft are known to have survived:

- 128451 - NAS North Island - San Diego, California. Prototype F7U-3. Stored awaiting cosmetic restoration. Originally slated for display at the USS Midway Museum in San Diego, California.[12] Formerly located at the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology in Socorro, New Mexico.

- 129554 - Snohomish County Airport - Paine Field, Everett, Washington. Ex VA-212. Purchased by Len Berryman from Geiger Field, Washington in May 1958 and displayed outside the Berryman War Memorial Park in Bridgeport, Washington from 1958 until 1992. In June 1992 it was sold to Tom Cathcart of Ephrata, Washington. Sold in September 2014, and awaiting transport to Phoenix, Arizona for further restoration to airworthy condition.[13]

- 129565 - Grand Prairie, Texas. Ex VA-212. Under cosmetic restoration by the Vought Retirees Group for eventual display at the USS Midway Museum in San Diego, California.[14]

- 129622 - Phoenix, Arizona. Ex VA-34 / VA-12 aircraft that was flown to Naval Air Reserve Training Unit (NARTU) Glenview, NAS Glenview, Illinois, where it was sporadically flown by Naval Air Reserve pilots and used for instruction of enlisted Naval Reserve aircraft maintenance personnel; ownership was then transferred to the Northbrook East Civic Association and the aircraft was moved to the Oaklane Elementary School for playground use. It was subsequently removed and dissected to be sold for its engines. Forward fuselage was part of Earl Reinart's collection in Mundelein, Illinois, while the rest of the aircraft went to J-46 dragster builder Fred Sibley in Elkhart, Indiana. Its components are currently reunited in the collection of F7U historian Al Casby.

- 129642 - Wings of Freedom Aviation Museum in Horsham, Pennsylvania.[15] Ex VA-12 aircraft flown to NAS Willow Grove in May 1957 to take part in an air show. Upon arrival the aircraft was stricken from active duty. It was transferred to the Naval Reserve for use as a ground training aircraft, and eventually placed as a gate guard in front of the base on US Route 611. The airframe has only 326.3 hours total flight time. Currently undergoing cosmetic refurbishment for a return to display status.

- 129655 - National Naval Aviation Museum at NAS Pensacola, Florida.[16] Ex VA-212. Cosmetically restored but incorrectly marked as an F7U-3M, this aircraft is a F7U-3. Formerly displayed at Griffith Park, California.

- 129685 - The aircraft collection of the late Walter Soplata in Newbury, Ohio.[17] Ex VA-12. Demilitarized and incomplete, it is exposed to the elements and unrestored

Specifications (F7U-3M)

Data from Naval Fighters Number Six,[18] Jane's Encyclopedia of Aviation[19]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 41 ft 3.5 in (12.586 m)

- Wingspan: 39 ft 8 in (12.1 m)

- Span wings folded: 22.3 ft (6.80 m)

- Height: 14 ft 0 in (4.27 m)

- Wing area: 496 sq ft (46.1 m2)

- Empty weight: 18,210 lb (8,260 kg)

- Gross weight: 26,840 lb (12,174 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 31,643 lb (14,353 kg)

- Powerplant: 2 × Westinghouse J46-WE-8B after-burning turbojet engines, 4,600 lbf (20 kN) thrust each dry, 6,000 lbf (27 kN) with afterburner

Performance

- Maximum speed: 606 kn (697 mph, 1,122 km/h) at sea level with Military power + afterburner

- Cruise speed: 490 kn (560 mph, 910 km/h) at 38,700 ft (11,796 m) to 42,700 ft (13,015 m)

- Stall speed: 112 kn (129 mph, 207 km/h) power off at take-off

- 93.2 kn (173 km/h) with approach power for landing

- Combat range: 800 nmi (920 mi, 1,500 km)

- Service ceiling: 40,600 ft (12,375 m)

- Rate of climb: 14,420 ft/min (73.3 m/s) with Military power + afterburner

- Time to altitude: 20,000 ft (6,096 m) in 5.6 minutes

- 30,000 ft (9,144 m) in 10.2 minutes

- Wing loading: 50.2 lb/sq ft (245 kg/m2)

- Thrust/weight: 0.45

- Take-off run: in calm conditions 1,595 ft (486 m) with Military power + afterburner

Armament

- Guns: 4 20mm M3 cannon above inlet ducts, 180 rpg

- Hardpoints: 4 with a capacity of 5,500 lb (2,500 kg),with provisions to carry combinations of:

- Missiles: 4 AAM-N-2 Sparrow I air-to-air missiles

See also

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

Related lists

References

- Notes

- Angelucci 1987, p. 447.

- "In the early jet age, pilots had good reason to fear the F7U". Air & Space Magazine. Retrieved 2019-01-13.

- LePage 2009, pp. 275–276.

- Schick and Meyer 1997, p. 167.

- O'Rourke, G.G, CAPT USN. "Of Hosenoses, Stoofs, and Lefthanded Spads." United States Naval Institute Proceedings, July 1968.

- Farrington, Robert M. (November 19, 1948). "New fighter unveiled". Reading Eagle. Pennsylvania. Associated Press. p. 43.

- "Navy swisher". Spokesman-Review. Spokane, Washington. (AP photo). November 22, 1948. p. 9.

- Angelluci 1987, p. 448.

- Powell 2008, p. 37.

- Gunston 1981, p. 235.

- Walton, Bill (July 14, 2018). "Ramp Strike: F7U Cutlass Crashes on the Deck of the Hancock". avgeekery.com. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- "F7U Cutlass/128451." Archived 2014-07-27 at the Wayback Machine USS Midway Museum. Retrieved: 16 January 2015.

- "F7U Cutlass/129554." aerialvisuals.ca. Retrieved: 8 April 2015.

- "F7U Cutlass/129565." Archived 2014-07-27 at the Wayback Machine USS Midway Museum. Retrieved: 29 October 2012.

- "F7U Cutlass/129642." Wings of Freedom Aviation Museum. Retrieved: 16 January 2015.

- "F7U Cutlass/129655." National Naval Aviation Museum. Retrieved: 16 January 2015.

- "F7U Cutlass/129685" aerialvisuals.ca. Retrieved: 16 January 2015.

- Ginter, Steve (1982). Chance Vought F7U Cutlass. Naval Fighters. Number 6. California: Steve Ginter. ISBN 0 942612 06 X.

- Taylor 1993, pp. 253–254.

- Bibliography

- Angelucci, Enzo. The American Fighter. Sparkford, Somerset, UK: Haynes Publishing Group, 1987. ISBN 0-85429-635-2.

- Ginter, Steve. Chance Vought F7U Cutlass (Naval Fighters Number Six). Simi Valley, California: Ginter Books, 1982. ISBN 0-942612-06-X.

- Green, William and Gerald Pollinger. The Aircraft of the World. London: Macdonald, 1955.

- Gunston, Bill. Fighters of the Fifties. Cambridge, UK: Patrick Stephens Limited, 1981. ISBN 0-85059-463-4.

- Lepage, Jean-Denis G.G. Aircraft of the Luftwaffe, 1935-1945: An Illustrated Guide. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2009. ISBN 978-0-7864-3937-9.

- Powell, R.R. "Boom". "Cutlass Tales". Flight Journal, Volume 13, Issue 4, August 2008.

- Schick, Walter and Ingolf Meyer. Luftwaffe Secret Projects: Fighters, 1939-1945. Hinckley, UK: Midland Publishing, 1997. ISBN 978-1-8578-0052-4.

- Taylor, John W. R. "Vought F7U Cutlass". Combat Aircraft of the World from 1909 to the Present. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1969. ISBN 0-425-03633-2.

- Taylor, Michael J.H., ed. "Chance Vought F7U Cutlass". Jane’s Encyclopedia of Aviation. New York: Crescent, 1993. ISBN 0-517-10316-8.

- Winchester, Jim, ed. "Vought F7U Cutlass". The World's Worst Aircraft: From Pioneering Failures to Multimillion Dollar Disasters. London: Amber Books Ltd., 2005. ISBN 1-904687-34-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vought F7U Cutlass. |