Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake

Naval Air Weapons Station (NAWS) China Lake[3] is a large military installation in California that supports the research, testing and evaluation programs of the U.S. Navy. It is part of Navy Region Southwest[4] under Commander, Navy Installations Command. It was originally known as Naval Ordnance Test Station (NOTS).

Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

USGS orthographic image showing the main runways at NAWS China Lake | |||||||||||||||||||

| Summary | |||||||||||||||||||

| Airport type | Military | ||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | |||||||||||||||||||

| Operator | |||||||||||||||||||

| Location | China Lake, California, U.S. | ||||||||||||||||||

| In use | 1943–present | ||||||||||||||||||

| Commander | CAPT Richard A. Wiley | ||||||||||||||||||

| Elevation AMSL | 2,284 ft / 696 m | ||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 35°41′08″N 117°41′31″W[1] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Website | www.cnic.navy.mil/ChinaLake | ||||||||||||||||||

| Runways | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

The installation is located in the Western Mojave Desert region of California, approximately 150 miles (240 km) north of Los Angeles. Occupying land in three counties – Kern, San Bernardino, and Inyo – the installation's closest neighbors are the city of Ridgecrest and the communities of Inyokern, Trona, and Darwin.

China Lake is the United States Navy's largest single landholding, representing 85% of the Navy's land for weapons and armaments research, development, acquisition, testing and evaluation (RDAT&E) use and 38% of the Navy's land holdings worldwide. In total, its two ranges and main site cover more than 1,100,000 acres (4,500 km2), an area larger than the state of Rhode Island. As of 2010, at least 95% of that land has been left undeveloped. The roughly $3 billion infrastructure of the installation consists of 2,132 buildings and facilities, 329 miles (529 km) of paved roads, and 1,801 miles (2,898 km) of unpaved roads.

The 19,600 square miles (51,000 km2) of restricted and controlled airspace at China Lake makes up 12% of California's total airspace. Jointly controlled by NAWS China Lake, Edwards Air Force Base and Fort Irwin, this airspace is known as the R-2508 Special Use Airspace Complex.

A 7.1 magnitude earthquake on July 5, 2019, whose epicenter was within the boundaries of NAWS China Lake, resulted in the facility being evaluated as "not mission capable”.[5]

Armitage Field

All aircraft operations at NAWS China Lake are conducted at Armitage Field, which has three runways with more than 26,000 feet (7,900 m) of taxiway. More than 20,000 manned and un-manned military sorties are conducted out of Armitage by U.S. Armed Forces each year.

Foreign military personnel also use the airfield and range to conduct more than 1,000 test and evaluation operations each year.

Tenant commands

The 620 active duty military, 4,166 civilian employees and 1,734 contractors that make up China Lake's workforce are employed across multiple tenant commands, including:[6]

- Naval Air Warfare Center Weapons Division

- Air Test and Evaluation Squadron 9 (VX-9)

- Air Test and Evaluation Squadron 31 (VX-31)

- Marine Aviation Detachment

- Explosive Ordnance Disposal Mobile Unit 3 Detachment

- Explosive Ordnance Disposal Testing and Evaluation Unit 1

- Naval Facilities Engineering Command Southwest Detachment

- Naval Construction Training Center Port Hueneme (Seabees)

History

China Lake is a dry lake. Its name comes from Chinese men harvesting borax from the lake bed, approximately 1.5 miles (2.4 km) south of Paxton Ranch. The operation was known locally as "The Little Chinese Borax Works".[7]

Naval Ordnance Test Station (NOTS)

In the midst of World War II, adequate facilities were needed by the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) for test and evaluation of rockets. At the same time, the Navy needed a new proving ground for aviation ordnance. Caltech's Charles C. Lauritsen and then U.S. Navy Commander Sherman E. Burroughs worked together to find a site that would meet both their needs.

In the early 1930s, an emergency landing field had been built by the Works Progress Administration in the Mojave Desert near the small town of Inyokern, California. Opened in 1935, the field was acquired by the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) in 1942. In November 1943 it was transferred to the Navy, which established China Lake as the Naval Ordnance Test Station (NOTS).

The NOTS mission was defined in a letter by the Secretary of the Navy as ".... a station having for its primary function the research, development and testing of weapons, and having additional function of furnishing primary training in the use of such weapons." Testing began within a month of the Station's formal establishment. The vast and sparsely populated desert with near perfect flying weather and practically unlimited visibility, proved an ideal location not only for test and evaluation activities, but also for a complete research and development establishment.

During 1944, NOTS worked on the development and testing of the 3.5-inch, 5-inch, HVAR and 11.75-inch (Tiny Tim) rockets.[8]

Manhattan Project funding was used to construct a new airfield at NOTS, with three runways, 10,000 feet (3,000 m), 7,700 feet (2,300 m) and 9,000 feet (2,700 m) long, each 200 feet (61 m) wide to accommodate the Boeing B-29 Superfortress bomber. Fuel storage was provided with a capacity of 200,000 US gallons (760,000 l) of gasoline and 20,000 US gallons (76,000 l) of oil. The airfield was opened on 1 June 1945, and named Armitage Field after Navy Lieutenant John Armitage, who was killed while testing a Tiny Tim rocket at NOTS in August 1944.[8][9][10]

Work done by Caltech at NOTS for the Manhattan Project - particularly the testing of bomb shapes dropped from B-29s - was included as part of codename Project Camel.

In 1950, NOTS scientists and engineers developed the air-intercept missile (AIM) 9 Sidewinder, which became the world's most used and most copied air-to-air missile. Other rockets and missiles developed or tested at China Lake include the Mighty Mouse, Zuni, Shrike, HARM, Joint Stand-Off Weapon (JSOW) and Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM). In June 1963, President John F. Kennedy visited NAWS China Lake for an air show and to see Michelson Lab.

Naval Weapons Center

In July 1967, NOTS China Lake and the Naval Ordnance Laboratory in Corona, California, became the Naval Weapons Center. The Corona facilities were closed and their functions transferred to the desert in 1971. In July 1979, the mission and functions of the National Parachute Test Range at Naval Air Facility El Centro were transferred to China Lake.

Naval Air Weapons Station

In January 1992, the Naval Weapons Center and the Pacific Missile Test Center Point Mugu were disestablished and joined with naval units at Kirtland AFB in Albuquerque and at the White Sands Missile Range at White Sands, NM as a single command - the Naval Air Warfare Center Weapons Division (NAWCWD) of the Naval Air Systems Command (NAVAIR). At the same time, the physical plant at China Lake was designated as a Naval Air Weapons Station and became host of the NAVAIR Weapons Division, performing the base-keeping functions.

In 1982 the community area of China Lake, including most of base housing, was annexed by the City of Ridgecrest. In 2013, Congress reserved China Lake's acreage for military use for an additional 25 years.

In 2014, U.S. Representative Kevin McCarthy of California introduced a bill to permanently designate Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake property for military use, arguing it would save taxpayer money and enhance the base's mission.[11] The bill would add 25,000 acres (10,000 ha), including about 7,500 acres (3,000 ha) that were part of a bombing range in San Bernardino County, as well as 19,000 acres (7,700 ha) along the station's southwest boundary. The Bureau of Land Management said that DoD needs could change in future decades and that it is a popular recreation area with trail riding, camp sites and hunting, and an important wildlife corridor, especially for the threatened desert tortoise.[11]

In July 2019, two large earthquakes struck Southern California; both had epicenters within the NAWS boundaries. The first, on July 4, a 6.4 magnitude quake, caused no injuries at NAWS, and the initial reports showed that all buildings were intact.[12] The second, a 7.1 magnitude earthquake on July 5, resulted in the facility being evaluated as "not mission capable”.[5]. The report shows that officials assessed all buildings, utilities and facilities — 3,598 structures in all — for 13 days after the earthquakes and found damage totaled $5.2 billion. Replacing buildings alone would cost $2.2 billion, but officials also must replace or repair specialized equipment, furniture, machine tools, telecommunication assets and other facilities.[13]

Weapons developed at China Lake

- AAM-N-5 Meteor

- AIM-9 Sidewinder

- AGM-62 Walleye

- AGM-45 Shrike

- BOAR (rocket)

- China Lake Grenade Launcher

- Gimlet (rocket)

- Holy Moses (rocket)

- Hopi (missile)

- LTV-N-4

- Ram (rocket)

- RUR-4 Weapon Alpha

- Terasca

- Tiny Tim (rocket)

- Tomahawk missile

- SLAM-ER

- CL-20

Other notable projects

Environment

Wildlife

The majority of the land at NAWS China Lake is undeveloped and provides habitat for more than 340 species of wildlife, including feral horses, feral burros (donkeys), Big Horn Sheep and endangered animals, such as the desert tortoise, Mojave ground squirrel and Mojave Tui Chub. The Mojave Tui Chub was introduced to China Lake's Lark Seep in 1971. Lark Seep is fed by the water outflow from a waste water treatment plant located at China Lake. The Tui Chub population has since grown and expanded to a population of around 6,000 in 2003.[14] The desert on which the installation is built is home to 650 plant types.

Petroglyphs

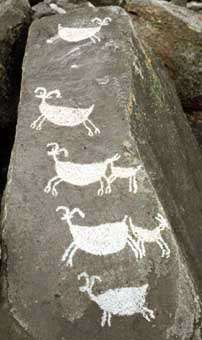

The area was once home to the Native American Coso People, whose presence here is marked by thousands of archaeological sites; the Coso traded with other tribes as far away as San Luis Obispo County, California. This locale was also a site used by European miners and settlers whose cabins and mining structures are extant throughout the Station.

The Coso Range Canyons are home to the Coso Rock Art District, an area of some 99 square miles (260 km2) which contains more than 50,000 documented petroglyphs,[15] the highest concentration of rock art in the Northern Hemisphere.

No one knows for sure how old these petroglyphs are. A broad range of dates can be inferred from archaeological sites in the area and some artifact forms depicted on the rocks. Archaeologists do not agree on their age, but in general it is believed that most petroglyphs are between one and three thousand years old.[16] Designs range from animals to abstract to anthropomorphic figures. Opinions vary widely whether the petroglyphs were made for ceremonial purposes, whether they are telling stories to pass along the mythology of their makers, or whether they are records of hunting hopes or successes, clan symbols or maps.

Declared a National Historic Landmark in 1964, the rock art in Little Petroglyph Canyon provides insights into the cultural heritage and knowledge of the desert's past. Everything in the canyon area is fully protected, including the obsidian chips and any artifacts or tools, as well as the petroglyphs and native vegetation and wildlife.

Little Petroglyph Canyon contains 20,000 documented images, which surpasses in number most other collections. It is open to the public for tours.[17]

Monorail

Remains of the Epsom Salts Monorail are signposted and visible within the site. The central rail, on which mining tractors pulled minerals from a mine to the nearest railway siding, was supported on wooden A frames of a low trestle.

Coso Geothermal Field

The Coso Geothermal Field is located within China Lake boundaries. The geothermal power plants located there began generating electricity in 1987[18] and were the Navy's first foray into producing clean power from the earth's thermal energy (heat). Total annual electricity production from the field amounts to 270 megawatts (360,000 hp), equivalent to more than 4 million barrels (640,000 m3) of oil. (One megawatt of electricity meets the needs of approximately 1,400 households.)

See also

References

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: China Lake Naval Weapons Center

- FAA Airport Master Record for NID (Form 5010 PDF), effective 2007-07-05

- "Welcome to Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake". Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake. United States Navy Commander, Navy Installations Command. Archived from the original on October 6, 2017. Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- Commander, Navy Region Southwest

- Salahieh, Nouran (July 6, 2019). "Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake in Ridgecrest Evacuated, Deemed Not 'Mission Capable' After Quake". KTLA. Retrieved July 7, 2019.

- "Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake: Tenant Commands". United States Navy. 2015. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

- Panlaqui, Carol, What's in a Name?, Maturango Museum, Ridgecrest, California (undated single sheet).

- "Naval Air Weapons Station, China Lake". The California State Military Museum. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- Gerrard-Gough & Christman 1978, pp. 175–176.

- "China lake Forecasters' Handbook – Section 1 Basic Description". Retrieved 3 September 2013.

- Freking, Kevin (April 29, 2014). "Obama administration opposes China Lake expansion". The Tribune. Archived from the original on May 5, 2014. Retrieved May 5, 2014.

- Antczak, John; Rodriguez, Olga (July 4, 2019). "Aftershocks following Southern California earthquake". WCYB. Retrieved July 7, 2019.

- Alejandra Reyes-Velarde (August 14, 2019). "Earthquakes caused up to $5 billion in damage to China Lake naval base". /www.stripes.com.

- "Currents" (PDF). China Lake and the Tui Chub. 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 16, 2004. Retrieved 2012-01-22.

- NPS Archeology Program: Coso Rock Art www.cr.nps.gov

- Shipstead, Maggie (October 29, 2015). "The Secret City". The California Sunday Magazine. Retrieved July 7, 2019.

- "Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake". www.cnic.navy.mil. Retrieved 2019-07-07.

- Monastero, Francis C. (September–October 2002). "Model for Success: An Overview of Industry-Military Cooperation in the Development of Power Operations at the Coso Geothermal Field in Southern California" (PDF). Geothermal Resources Council (GRC) Bulletin. Retrieved July 7, 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake. |

- Official sites

- Official Naval Air Weapons Station website

- NAVAIR Home

- NAVAIR Weapons Division

- Air Test and Evaluation Squadron Nine

- Air Test and Evaluation Squadron Thirty One

- Museum

- Naval History & Heritage Command (History.navy.mil): U.S. Naval Museum of Armament and Technology at China Lake — official website

- Chinalakemuseum.org: U.S. Naval China Lake Museum of Armament and Technology

- Chinalakemuseum.org: U.S. Naval China Lake Museum of Armament and Technology Foundation website

- Other

- 2002 NAWS China Lake Welcome brochure

- GlobalSecurity.org: China Lake

- Astronautix.com: China Lake

- The California State Military Museum

- China Lake Alumni.org

- AirTime, Spring 2007, Volume 3, Issue 1

- FAA Airport Diagram for NAWS China Lake (PDF), effective August 13, 2020

- Resources for this U.S. military airport:

- FAA airport information for NID

- AirNav airport information for KNID

- NOAA/NWS latest weather observations

- SkyVector aeronautical chart for KNID

- China Lake logos including the "rocket-ridin' rabbit"