Euphrates

The Euphrates (/juːˈfreɪtiːz/ (![]()

| Euphrates | |

|---|---|

| |

Map of the combined Tigris–Euphrates drainage basin (in yellow) | |

| Etymology | from Greek, from Old Persian Ufrātu, from Elamite ú-ip-ra-tu-iš |

| Location | |

| Country | Turkey, Iraq, Syria |

| Basin area | Turkey, Syria, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Iran |

| Cities | Birecik, Raqqa, Deir ez-Zor, Mayadin, Haditha, Ramadi, Habbaniyah, Fallujah, Kufa, Samawah, Nasiriyah |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Murat Su, Turkey |

| • elevation | 3,520 m (11,550 ft) |

| 2nd source | |

| • location | Kara Su, Turkey |

| • elevation | 3,290 m (10,790 ft) |

| Source confluence | |

| • location | Keban, Turkey |

| • elevation | 610 m (2,000 ft) |

| Mouth | Shatt al-Arab |

• location | Al-Qurnah, Basra Governorate, Iraq |

• coordinates | 31°0′18″N 47°26′31″E |

| Length | Approx. 2,800 km (1,700 mi) |

| Basin size | Approx. 500,000 km2 (190,000 sq mi) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Hīt |

| • average | 356 m3/s (12,600 cu ft/s) |

| • minimum | 58 m3/s (2,000 cu ft/s) |

| • maximum | 2,514 m3/s (88,800 cu ft/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Balikh, Khabur |

| • right | Sajur |

Etymology

The Ancient Greek form Euphrátēs (Ancient Greek: Εὐφράτης, as if from Greek εὖ "good" and ϕράζω "I announce or declare") was adapted from Old Persian 𐎢𐎳𐎼𐎠𐎬𐎢 Ufrātu,[1] itself from Elamite 𒌑𒅁𒊏𒌅𒅖 ú-ip-ra-tu-iš. The Elamite name is ultimately derived from a name spelt in cuneiform as 𒌓𒄒𒉣 , which read as Sumerian language is "Buranuna" and read as Akkadian language is "Purattu"; many cuneiform signs have a Sumerian pronunciation and an Akkadian pronunciation, taken from a Sumerian word and an Akkadian word that mean the same. In Akkadian the river was called Purattu,[2] which has been perpetuated in Semitic languages (cf. Arabic: الفرات, romanized: al-Furāt; Syriac: ̇ܦܪܬ Pǝrāt) and in other nearby languages of the time (cf. Hurrian Puranti, Sabarian Uruttu). The Elamite, Akkadian, and possibly Sumerian forms are suggested to be from an unrecorded substrate language.[3] Tamaz V. Gamkrelidze and Vyacheslav Ivanov suggest the Proto-Sumerian *burudu "copper" (Sumerian urudu) as an origin, with an explanation that Euphrates was the river by which the copper ore was transported in rafts, since Mesopotamia was the center of copper metallurgy during the period.[4] The name is Yeprat in Armenian (Եփրատ), Perat in Hebrew (פרת), Fırat in Turkish and Firat in Kurdish.

The earliest references to the Euphrates come from cuneiform texts found in Shuruppak and pre-Sargonic Nippur in southern Iraq and date to the mid-3rd millennium BCE. In these texts, written in Sumerian, the Euphrates is called Buranuna (logographic: UD.KIB.NUN). The name could also be written KIB.NUN.(NA) or dKIB.NUN, with the prefix "d" indicating that the river was a divinity. In Sumerian, the name of the city of Sippar in modern-day Iraq was also written UD.KIB.NUN, indicating a historically strong relationship between the city and the river.

Course

The Euphrates is the longest river of Western Asia.[5] It emerges from the confluence of the Kara Su or Western Euphrates (450 kilometres (280 mi)) and the Murat Su or Eastern Euphrates (650 kilometres (400 mi)) 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) upstream from the town of Keban in southeastern Turkey.[6] Daoudy and Frenken put the length of the Euphrates from the source of the Murat River to the confluence with the Tigris at 3,000 kilometres (1,900 mi), of which 1,230 kilometres (760 mi) is in Turkey, 710 kilometres (440 mi) in Syria and 1,060 kilometres (660 mi) in Iraq.[7][8] The same figures are given by Isaev and Mikhailova.[9] The length of the Shatt al-Arab, which connects the Euphrates and the Tigris with the Persian Gulf, is given by various sources as 145–195 kilometres (90–121 mi).[10]

Both the Kara Su and the Murat Su rise northwest from Lake Van at elevations of 3,290 metres (10,790 ft) and 3,520 metres (11,550 ft) amsl, respectively.[11] At the location of the Keban Dam, the two rivers, now combined into the Euphrates, have dropped to an elevation of 693 metres (2,274 ft) amsl. From Keban to the Syrian–Turkish border, the river drops another 368 metres (1,207 ft) over a distance of less than 600 kilometres (370 mi). Once the Euphrates enters the Upper Mesopotamian plains, its grade drops significantly; within Syria the river falls 163 metres (535 ft) while over the last stretch between Hīt and the Shatt al-Arab the river drops only 55 metres (180 ft).[6][12]

Discharge

The Euphrates receives most of its water in the form of rainfall and melting snow, resulting in peak volumes during the months April through May. Discharge in these two months accounts for 36 percent of the total annual discharge of the Euphrates, or even 60–70 percent according to one source, while low runoff occurs in summer and autumn.[9][13] The average natural annual flow of the Euphrates has been determined from early- and mid-twentieth century records as 20.9 cubic kilometres (5.0 cu mi) at Keban, 36.6 cubic kilometres (8.8 cu mi) at Hīt and 21.5 cubic kilometres (5.2 cu mi) at Hindiya.[14] However, these averages mask the high inter-annual variability in discharge; at Birecik, just north of the Syro–Turkish border, annual discharges have been measured that ranged from a low volume of 15.3 cubic kilometres (3.7 cu mi) in 1961 to a high of 42.7 cubic kilometres (10.2 cu mi) in 1963.[15]

The discharge regime of the Euphrates has changed dramatically since the construction of the first dams in the 1970s. Data on Euphrates discharge collected after 1990 show the impact of the construction of the numerous dams in the Euphrates and of the increased withdrawal of water for irrigation. Average discharge at Hīt after 1990 has dropped to 356 cubic metres (12,600 cu ft) per second (11.2 cubic kilometres (2.7 cu mi) per year). The seasonal variability has equally changed. The pre-1990 peak volume recorded at Hīt was 7,510 cubic metres (265,000 cu ft) per second, while after 1990 it is only 2,514 cubic metres (88,800 cu ft) per second. The minimum volume at Hīt remained relatively unchanged, rising from 55 cubic metres (1,900 cu ft) per second before 1990 to 58 cubic metres (2,000 cu ft) per second afterward.[16][17]

Tributaries

In Syria, three rivers add their water to the Euphrates; the Sajur, the Balikh and the Khabur. These rivers rise in the foothills of the Taurus Mountains along the Syro–Turkish border and add comparatively little water to the Euphrates. The Sajur is the smallest of these tributaries; emerging from two streams near Gaziantep and draining the plain around Manbij before emptying into the reservoir of the Tishrin Dam. The Balikh receives most of its water from a karstic spring near 'Ayn al-'Arus and flows due south until it reaches the Euphrates at the city of Raqqa. In terms of length, drainage basin and discharge, the Khabur is the largest of these three. Its main karstic springs are located around Ra's al-'Ayn, from where the Khabur flows southeast past Al-Hasakah, where the river turns south and drains into the Euphrates near Busayrah. Once the Euphrates enters Iraq, there are no more natural tributaries to the Euphrates, although canals connecting the Euphrates basin with the Tigris basin exist.[18][19]

| Name | Length | Watershed size | Discharge | Bank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kara Su | 450 km (280 mi) | 22,000 km2 (8,500 sq mi) | Confluence | |

| Murat River | 650 km (400 mi) | 40,000 km2 (15,000 sq mi) | Confluence | |

| Sajur River | 108 km (67 mi) | 2,042 km2 (788 sq mi) | 4.1 m3/s (145 cu ft/s) | Right |

| Balikh River | 100 km (62 mi) | 14,400 km2 (5,600 sq mi) | 6 m3/s (212 cu ft/s) | Left |

| Khabur River | 486 km (302 mi) | 37,081 km2 (14,317 sq mi) | 45 m3/s (1,600 cu ft/s) | Left |

Drainage basin

The drainage basins of the Kara Su and the Murat River cover an area of 22,000 square kilometres (8,500 sq mi) and 40,000 square kilometres (15,000 sq mi), respectively.[6] Estimates of the area of the Euphrates drainage basin vary widely; from a low 233,000 square kilometres (90,000 sq mi) to a high 766,000 square kilometres (296,000 sq mi).[9] Recent estimates put the basin area at 388,000 square kilometres (150,000 sq mi),[6] 444,000 square kilometres (171,000 sq mi)[7][20] and 579,314 square kilometres (223,674 sq mi).[21] The greater part of the Euphrates basin is located in Turkey, Syria, and Iraq. According to both Daoudy and Frenken, Turkey's share is 28 percent, Syria's is 17 percent and that of Iraq is 40 percent.[7][8] Isaev and Mikhailova estimate the percentages of the drainage basin lying within Turkey, Syria and Iraq at 33, 20 and 47 percent respectively.[9] Some sources estimate that approximately 15 percent of the drainage basin is located within Saudi Arabia, while a small part falls inside the borders of Kuwait.[7][8] Finally, some sources also include Jordan in the drainage basin of the Euphrates; a small part of the eastern desert (220 square kilometres (85 sq mi)) drains toward the east rather than to the west.[9][22]

Natural history

.jpg)

The Euphrates flows through a number of distinct vegetation zones. Although millennia-long human occupation in most parts of the Euphrates basin has significantly degraded the landscape, patches of original vegetation remain. The steady drop in annual rainfall from the sources of the Euphrates toward the Persian Gulf is a strong determinant for the vegetation that can be supported. In its upper reaches the Euphrates flows through the mountains of Southeast Turkey and their southern foothills which support a xeric woodland. Plant species in the moister parts of this zone include various oaks, pistachio trees, and Rosaceae (rose/plum family). The drier parts of the xeric woodland zone supports less dense oak forest and Rosaceae. Here can also be found the wild variants of many cereals, including einkorn wheat, emmer wheat, oat and rye.[23] South of this zone lies a zone of mixed woodland-steppe vegetation. Between Raqqa and the Syro–Iraqi border the Euphrates flows through a steppe landscape. This steppe is characterised by white wormwood (Artemisia herba-alba) and Chenopodiaceae. Throughout history, this zone has been heavily overgrazed due to the practicing of sheep and goat pastoralism by its inhabitants.[24] Southeast of the border between Syria and Iraq starts true desert. This zone supports either no vegetation at all or small pockets of Chenopodiaceae or Poa sinaica. Although today nothing of it survives due to human interference, research suggests that the Euphrates Valley would have supported a riverine forest. Species characteristic of this type of forest include the Oriental plane, the Euphrates poplar, the tamarisk, the ash and various wetland plants.[25]

Among the fish species in the Tigris–Euphrates basin, the family of the Cyprinidae are the most common, with 34 species out of 52 in total.[26] Among the Cyprinids, the mangar has good sport fishing qualities, leading the British to nickname it "Tigris salmon." The Rafetus euphraticus is an endangered soft-shelled turtle that is limited to the Tigris–Euphrates river system.[27]

The Neo-Assyrian palace reliefs from the 1st millennium BCE depict lion and bull hunts in fertile landscapes.[29] Sixteenth to nineteenth century European travellers in the Syrian Euphrates basin reported on an abundance of animals living in the area, many of which have become rare or even extinct. Species like gazelle, onager and the now-extinct Arabian ostrich lived in the steppe bordering the Euphrates valley, while the valley itself was home to the wild boar. Carnivorous species include the gray wolf, the golden jackal, the red fox, the leopard and the lion. The Syrian brown bear can be found in the mountains of Southeast Turkey. The presence of European beaver has been attested in the bone assemblage of the prehistoric site of Abu Hureyra in Syria, but the beaver has never been sighted in historical times.[30]

River

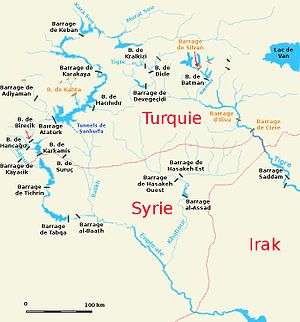

The Hindiya Barrage on the Iraqi Euphrates, based on plans by British civil engineer William Willcocks and finished in 1913, was the first modern water diversion structure built in the Tigris–Euphrates river system.[31] The Hindiya Barrage was followed in the 1950s by the Ramadi Barrage and the nearby Abu Dibbis Regulator, which serve to regulate the flow regime of the Euphrates and to discharge excess flood water into the depression that is now Lake Habbaniyah. Iraq's largest dam on the Euphrates is the Haditha Dam; a 9-kilometre-long (5.6 mi) earth-fill dam creating Lake Qadisiyah.[32] Syria and Turkey built their first dams in the Euphrates in the 1970s. The Tabqa Dam in Syria was completed in 1973 while Turkey finished the Keban Dam, a prelude to the immense Southeastern Anatolia Project, in 1974. Since then, Syria has built two more dams in the Euphrates, the Baath Dam and the Tishrin Dam, and plans to build a fourth dam – the Halabiye Dam – between Raqqa and Deir ez-Zor.[33] The Tabqa Dam is Syria's largest dam and its reservoir (Lake Assad) is an important source of irrigation and drinking water. It was planned that 640,000 hectares (2,500 sq mi) should be irrigated from Lake Assad, but in 2000 only 100,000–124,000 hectares (390–480 sq mi) had been realized.[34][35] Syria also built three smaller dams on the Khabur and its tributaries.[36]

With the implementation of the Southeastern Anatolia Project (Turkish: Güneydoğu Anadolu Projesi, or GAP) in the 1970s, Turkey launched an ambitious plan to harness the waters of the Tigris and the Euphrates for irrigation and hydroelectricity production and provide an economic stimulus to its southeastern provinces.[37] GAP affects a total area of 75,000 square kilometres (29,000 sq mi) and approximately 7 million people; representing about 10 percent of Turkey's total surface area and population, respectively. When completed, GAP will consist of 22 dams – including the Keban Dam – and 19 power plants and provide irrigation water to 1,700,000 hectares (6,600 sq mi) of agricultural land, which is about 20 percent of the irrigable land in Turkey.[38] C. 910,000 hectares (3,500 sq mi) of this irrigated land is located in the Euphrates basin.[39] By far the largest dam in GAP is the Atatürk Dam, located c. 55 kilometres (34 mi) northwest of Şanlıurfa. This 184-metre-high (604 ft) and 1,820-metre-long (5,970 ft) dam was completed in 1992; thereby creating a reservoir that is the third-largest lake in Turkey. With a maximum capacity of 48.7 cubic kilometres (11.7 cu mi), the Atatürk Dam reservoir is large enough to hold the entire annual discharge of the Euphrates.[40] Completion of GAP was scheduled for 2010 but has been delayed because the World Bank has withheld funding due to the lack of an official agreement on water sharing between Turkey and the downstream states on the Euphrates and the Tigris.[41]

Apart from barrages and dams, Iraq has also created an intricate network of canals connecting the Euphrates with Lake Habbaniyah, Lake Tharthar, and Abu Dibbis reservoir; all of which can be used to store excess floodwater. Via the Shatt al-Hayy, the Euphrates is connected with the Tigris. The largest canal in this network is the Main Outfall Drain or so-called "Third River;" constructed between 1953 and 1992. This 565-kilometre-long (351 mi) canal is intended to drain the area between the Euphrates and the Tigris south of Baghdad to prevent soil salinization from irrigation. It also allows large freight barges to navigate up to Baghdad.[42][43][44]

Environmental and social effects

The construction of the dams and irrigation schemes on the Euphrates has had a significant impact on the environment and society of each riparian country. The dams constructed as part of GAP – in both the Euphrates and the Tigris basins – have affected 382 villages and almost 200,000 people have been resettled elsewhere. The largest number of people was displaced by the building of the Atatürk Dam, which alone affected 55,300 people.[45] A survey among those who were displaced showed that the majority were unhappy with their new situation and that the compensation they had received was considered insufficient.[46] The flooding of Lake Assad led to the forced displacement of c. 4,000 families, who were resettled in other parts of northern Syria as part of a now abandoned plan to create an "Arab belt" along the borders with Turkey and Iraq.[47][48][49]

Apart from the changes in the discharge regime of the river, the numerous dams and irrigation projects have also had other effects on the environment. The creation of reservoirs with large surfaces in countries with high average temperatures has led to increased evaporation; thereby reducing the total amount of water that is available for human use. Annual evaporation from reservoirs has been estimated at 2 cubic kilometres (0.48 cu mi) in Turkey, 1 cubic kilometre (0.24 cu mi) in Syria and 5 cubic kilometres (1.2 cu mi) in Iraq.[50] Water quality in the Iraqi Euphrates is low because irrigation water tapped in Turkey and Syria flows back into the river, together with dissolved fertilizer chemicals used on the fields.[51] The salinity of Euphrates water in Iraq has increased as a result of upstream dam construction, leading to lower suitability as drinking water.[52] The many dams and irrigation schemes, and the associated large-scale water abstraction, have also had a detrimental effect on the ecologically already fragile Mesopotamian Marshes and on freshwater fish habitats in Iraq.[53][54]

The inundation of large parts of the Euphrates valley, especially in Turkey and Syria, has led to the flooding of many archaeological sites and other places of cultural significance.[55] Although concerted efforts have been made to record or save as much of the endangered cultural heritage as possible, many sites are probably lost forever. The combined GAP projects on the Turkish Euphrates have led to major international efforts to document the archaeological and cultural heritage of the endangered parts of the valley. Especially the flooding of Zeugma with its unique Roman mosaics by the reservoir of the Birecik Dam has generated much controversy in both the Turkish and international press.[56][57] The construction of the Tabqa Dam in Syria led to a large international campaign coordinated by UNESCO to document the heritage that would disappear under the waters of Lake Assad. Archaeologists from numerous countries excavated sites ranging in date from the Natufian to the Abbasid period, and two minarets were dismantled and rebuilt outside the flood zone. Important sites that have been flooded or affected by the rising waters of Lake Assad include Mureybet, Emar and Abu Hureyra.[58] A similar international effort was made when the Tishrin Dam was constructed, which led, among others, to the flooding of the important Pre-Pottery Neolithic B site of Jerf el-Ahmar.[59] An archaeological survey and rescue excavations were also carried out in the area flooded by Lake Qadisiya in Iraq.[60] Parts of the flooded area have recently become accessible again due to the drying up of the lake, resulting not only in new possibilities for archaeologists to do more research, but also providing opportunities for looting, which has been rampant elsewhere in Iraq in the wake of the 2003 invasion.

History

Palaeolithic to Chalcolithic periods

The early occupation of the Euphrates basin was limited to its upper reaches; that is, the area that is popularly known as the Fertile Crescent. Acheulean stone artifacts have been found in the Sajur basin and in the El Kowm oasis in the central Syrian steppe; the latter together with remains of Homo erectus that were dated to 450,000 years old.[62][63] In the Taurus Mountains and the upper part of the Syrian Euphrates valley, early permanent villages such as Abu Hureyra – at first occupied by hunter-gatherers but later by some of the earliest farmers, Jerf el-Ahmar, Mureybet and Nevalı Çori became established from the eleventh millennium BCE onward.[64] In the absence of irrigation, these early farming communities were limited to areas where rainfed agriculture was possible, that is, the upper parts of the Syrian Euphrates as well as Turkey.[65] Late Neolithic villages, characterized by the introduction of pottery in the early 7th millennium BCE, are known throughout this area.[66] Occupation of lower Mesopotamia started in the 6th millennium and is generally associated with the introduction of irrigation, as rainfall in this area is insufficient for dry agriculture. Evidence for irrigation has been found at several sites dating to this period, including Tell es-Sawwan.[67] During the 5th millennium BCE, or late Ubaid period, northeastern Syria was dotted by small villages, although some of them grew to a size of over 10 hectares (25 acres).[68] In Iraq, sites like Eridu and Ur were already occupied during the Ubaid period.[69] Clay boat models found at Tell Mashnaqa along the Khabur indicate that riverine transport was already practiced during this period.[70] The Uruk period, roughly coinciding with the 4th millennium BCE, saw the emergence of truly urban settlements across Mesopotamia. Cities like Tell Brak and Uruk grew to over 100 hectares (250 acres) in size and displayed monumental architecture.[71] The spread of southern Mesopotamian pottery, architecture and sealings far into Turkey and Iran has generally been interpreted as the material reflection of a widespread trade system aimed at providing the Mesopotamian cities with raw materials. Habuba Kabira on the Syrian Euphrates is a prominent example of a settlement that is interpreted as an Uruk colony.[72][73]

Ancient history

During the Jemdet Nasr (3600–3100 BCE) and Early Dynastic periods (3100–2350 BCE), southern Mesopotamia experienced a growth in the number and size of settlements, suggesting strong population growth. These settlements, including Sumero-Akkadian sites like Sippar, Uruk, Adab and Kish, were organized in competing city-states.[74] Many of these cities were located along canals of the Euphrates and the Tigris that have since dried up, but that can still be identified from remote sensing imagery.[75] A similar development took place in Upper Mesopotamia, Subartu and Assyria, although only from the mid 3rd millennium and on a smaller scale than in Lower Mesopotamia. Sites like Ebla, Mari and Tell Leilan grew to prominence for the first time during this period.[76]

Large parts of the Euphrates basin were for the first time united under a single ruler during the Akkadian Empire (2335–2154 BC) and Ur III empires, which controlled – either directly or indirectly through vassals – large parts of modern-day Iraq and northeastern Syria.[77] Following their collapse, the Old Assyrian Empire (1975–1750 BCE) and Mari asserted their power over northeast Syria and northern Mesopotamia, while southern Mesopotamia was controlled by city-states like Isin, Kish and Larsa before their territories were absorbed by the newly emerged state of Babylonia under Hammurabi in the early to mid 18th century BCE.[78]

In the second half of the 2nd millennium BCE, the Euphrates basin was divided between Kassite Babylon in the south and Mitanni, Assyria and the Hittite Empire in the north, with the Middle Assyrian Empire (1365–1020 BC) eventually eclipsing the Hittites, Mitanni and Kassite Babylonians.[79] Following the end of the Middle Assyrian Empire in the late 11th century BCE, struggles broke out between Babylonia and Assyria over the control of the Iraqi Euphrates basin. The Neo-Assyrian Empire (935–605 BC) eventually emerged victorious out of this conflict and also succeeded in gaining control of the northern Euphrates basin in the first half of the 1st millennium BCE.[80]

In the centuries to come, control of the wider Euphrates basin shifted from the Neo-Assyrian Empire (which collapsed between 612 and 599 BC) to the short lived Median Empire (612–546 BC) and equally brief Neo-Babylonian Empire (612–539 BC) in the last years of the 7th century BC, and eventually to the Achaemenid Empire (539–333 BC).[81] The Achaemenid Empire was in turn overrun by Alexander the Great, who defeated the last king Darius III and died in Babylon in 323 BCE.[82]

Subsequent to this, the region came under the control of the Seleucid Empire (312–150 BC), Parthian Empire (150–226 AD) (during which several Neo-Assyrian states such as Adiabene came to rule certain regions of the Euphrates), and was fought over by the Roman Empire, its succeeding Byzantine Empire and the Sassanid Empire (226–638 AD), until the Islamic conquest of the mid 7th century AD. The Battle of Karbala took place near the banks of this river in 680 AD.

In the north, the river served as a border between Greater Armenia (331 BC–428 AD) and Lesser Armenia (the latter became a Roman province in the 1st century BC).

Modern era

After World War I, the borders in Southwest Asia were redrawn in the Treaty of Lausanne (1923), when the Ottoman Empire was partitioned. Clause 109 of the treaty stipulated that the three riparian states of the Euphrates (at that time Turkey, France for its Syrian mandate and the United Kingdom for its mandate of Iraq) had to reach a mutual agreement on the use of its water and on the construction of any hydraulic installation.[83] An agreement between Turkey and Iraq signed in 1946 required Turkey to report to Iraq on any hydraulic changes it made on the Tigris–Euphrates river system, and allowed Iraq to construct dams on Turkish territory to manage the flow of the Euphrates.[84]

The river featured on the coat of arms of Iraq from 1932–1959.

Turkey and Syria completed their first dams on the Euphrates – the Keban Dam and the Tabqa Dam, respectively – within one year of each other and filling of the reservoirs commenced in 1975. At the same time, the area was hit by severe drought and river flow toward Iraq was reduced from 15.3 cubic kilometres (3.7 cu mi) in 1973 to 9.4 cubic kilometres (2.3 cu mi) in 1975. This led to an international crisis during which Iraq threatened to bomb the Tabqa Dam. An agreement was eventually reached between Syria and Iraq after intervention by Saudi Arabia and the Soviet Union.[85][86] A similar crisis, although not escalating to the point of military threats, occurred in 1981 when the Keban Dam reservoir had to be refilled after it had been almost emptied to temporarily increase Turkey's hydroelectricity production.[87] In 1984, Turkey unilaterally declared that it would ensure a flow of at least 500 cubic metres (18,000 cu ft) per second, or 16 cubic kilometres (3.8 cu mi) per year, into Syria, and in 1987 a bilateral treaty to that effect was signed between the two countries.[88] Another bilateral agreement from 1989 between Syria and Iraq settles the amount of water flowing into Iraq at 60 percent of the amount that Syria receives from Turkey.[84][86][89] In 2008, Turkey, Syria and Iraq instigated the Joint Trilateral Committee (JTC) on the management of the water in the Tigris–Euphrates basin and on 3 September 2009 a further agreement was signed to this effect.[90] On 15 April 2014, Turkey began to reduce the flow of the Euphrates into Syria and Iraq. The flow was cut off completely on 16 May 2014 resulting in the Euphrates terminating at the Turkish–Syrian border.[91] This was in violation of an agreement reached in 1987 in which Turkey committed to releasing a minimum of 500 cubic metres (18,000 cu ft) of water per second at the Turkish–Syrian border.[92]

During the Syrian civil war and the Iraqi Civil War, much of the Euphrates was controlled by the Islamic State from 2014 until 2017, when the terrorist group began losing land and was eventually defeated territorially in Syria at the Battle of Baghouz and in Iraq in the Western Iraq offensive respectively.[93]

Economy

Throughout history, the Euphrates has been of vital importance to those living along its course. With the construction of large hydropower stations, irrigation schemes, and pipelines capable of transporting water over large distances, many more people now depend on the river for basic amenities such as electricity and drinking water than in the past. Syria's Lake Assad is the most important source of drinking water for the city of Aleppo, 75 kilometres (47 mi) to the west of the river valley.[94] The lake also supports a modest state-operated fishing industry.[95] Through a newly restored power line, the Haditha Dam in Iraq provides electricity to Baghdad.[96]

Notes

- Negev & Gibson 2001, p. 169

- Woods 2005

- Witzel, Michael (2006). "Early Loan Words in Western Central Asia: Substrates, Migrations and Trade" (PDF). In Mair, Victor H. (ed.). Contact and Exchange in the Ancient World. University of Hawai'i Press.

- Gamkrelidze, Thomas; V. Ivanov, Vjaceslav (1995), Indo-European and the Indo-Europeans: A Reconstruction and Historical Analysis of a Proto-Language and Proto-Culture, Walter de Gruyter, p. 616, ISBN 9783110815030

- Zarins 1997, p. 287

- Iraqi Ministries of Environment, Water Resources and Municipalities and Public Works 2006a, p. 71

- Daoudy 2005, p. 63

- Frenken 2009, p. 65

- Isaev & Mikhailova 2009, p. 384

- Isaev & Mikhailova 2009, p. 388

- Mutin 2003, p. 2

- Bilen 1994, p. 100

- Iraqi Ministries of Environment, Water Resources and Municipalities and Public Works 2006a, p. 91

- Isaev & Mikhailova 2009, p. 385

- Kolars 1994, p. 47

- Isaev & Mikhailova 2009, p. 386

- Iraqi Ministries of Environment, Water Resources and Municipalities and Public Works 2006a, p. 94

- Hillel 1994, p. 95

- Hole & Zaitchik 2007

- Shahin 2007, p. 251

- Partow 2001, p. 4

- Frenken 2009, p. 63

- Moore, Hillman & Legge 2000, pp. 52–58

- Moore, Hillman & Legge 2000, pp. 63–65

- Moore, Hillman & Legge 2000, pp. 69–71

- Coad 1996

- Gray 1864, pp. 81–82

- Thomason 2001

- Moore, Hillman & Legge 2000, pp. 85–91

- Kliot 1994, p. 117

- Iraqi Ministries of Environment, Water Resources and Municipalities and Public Works 2006b, pp. 20–21

- Jamous 2009

- Elhadj 2008

- Mutin 2003, p. 4

- Mutin 2003, p. 5

- Kolars & Mitchell 1991, p. 17

- Jongerden 2010, p. 138

- Frenken 2009, p. 62

- Isaev & Mikhailova 2009, pp. 383–384

- Jongerden 2010, p. 139

- Kolars 1994, p. 53

- Daoudy 2005, p. 127

- Hillel 1994, p. 100

- Sahan et al. 2001, p. 10

- Sahan et al. 2001, p. 11

- Anonymous 2009, p. 11

- McDowall 2004, p. 475

- Hillel 1994, p. 107

- Hillel 1994, p. 103

- Frenken 2009, p. 212

- Rahi & Halihan 2009

- Jawad 2003

- Muir 2009

- McClellan 1997

- Tanaka 2007

- Steele 2005, pp. 52–53

- Bounni 1979

- del Olmo Lete & Montero Fenollós 1999

- Abdul-Amir 1988

- Muhesen 2002, p. 102

- Schmid et al. 1997

- Sagona & Zimansky 2009, pp. 49–54

- Akkermans & Schwartz 2003, p. 74

- Akkermans & Schwartz 2003, p. 110

- Helbaek 1972

- Akkermans & Schwartz 2003, pp. 163–166

- Oates 1960

- Akkermans & Schwartz 2003, pp. 167–168

- Ur, Karsgaard & Oates 2007

- Akkermans & Schwartz 2003, p. 203

- van de Mieroop 2007, pp. 38–39

- Adams 1981

- Hritz & Wilkinson 2006

- Akkermans & Schwartz 2003, p. 233

- van de Mieroop 2007, p. 63

- van de Mieroop 2007, p. 111

- van de Mieroop 2007, p. 132

- van de Mieroop 2007, p. 241

- van de Mieroop 2007, p. 270

- van de Mieroop 2007, p. 287

- Treaty of peace with Turkey signed at Lausanne, World War I Document Archive, retrieved 19 December 2010

- Geopolicity 2010, pp. 11–12

- Shapland 1997, pp. 117–118

- Kaya 1998

- Kolars 1994, p. 49

- Daoudy 2005, pp. 169–170

- Daoudy 2005, pp. 172

- Geopolicity 2010, p. 16

- Anjarini, Suhaib (30 May 2014). "A new Turkish aggression against Syria: Ankara suspends pumping Euphrates' water". Al Akhbar. Archived from the original on 16 June 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- Eupherates of Syria Cut Off by Turkey. 30 May 2014 – via YouTube.

- "Mideast Water Wars: In Iraq, A Battle for Control of Water". Yale E360. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- Shapland 1997, p. 110

- Krouma 2006

- O'Hara 2004, p. 3

References

- Abdul-Amir, Sabah Jasim (1988), Archaeological Survey of Ancient Settlements and Irrigation Systems in the Middle Euphrates Region of Mesopotamia (PhD thesis), Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, OCLC 615058488

- Adams, Robert McC. (1981), Heartland of Cities. Surveys of Ancient Settlement and Land Use on the Central Floodplain of the Euphrates, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-00544-5

- Akkermans, Peter M. M. G.; Schwartz, Glenn M. (2003), The Archaeology of Syria. From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (ca. 16,000–300 BC), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-79666-0

- Anonymous (2009), Group Denial. Repression of Kurdish Political and Cultural Rights in Syria (PDF), New York: Human Rights Watch, OCLC 472433635

- Bilen, Özden (1994), "Prospects for Technical Cooperation in the Euphrates–Tigris Basin", in Biswas, Asit K. (ed.), International Waters of the Middle East: From Euphrates-Tigris to Nile, Oxford University Press, pp. 95–116, ISBN 978-0-19-854862-1

- Bounni, Adnan (1979), "Campaign and Exhibition from the Euphrates in Syria", The Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research, 44: 1–7, JSTOR 3768538

- Coad, B.W. (1996), "Zoogeography of the Fishes of the Tigris-Euphrates Basin", Zoology in the Middle East, 13: 51–70, doi:10.1080/09397140.1996.10637706, ISSN 0939-7140

- Daoudy, Marwa (2005), Le Partage des Eaux entre la Syrie, l'Irak et la Turquie. Négociation, Sécurité et Asymétrie des Pouvoirs, Moyen-Orient (in French), Paris: CNRS, ISBN 2-271-06290-X

- del Olmo Lete, Gregorio; Montero Fenollós, Juan Luis, eds. (1999), Archaeology of the Upper Syrian Euphrates, the Tishrin Dam area: Proceedings of the International Symposium held at Barcelona, January 28th–30th, 1998, Barcelona: AUSA, ISBN 978-84-88810-43-4

- Elhadj, Elie (2008), "Dry Aquifers in Arab Countries and the Looming Food Crisis", Middle East Review of International Affairs, 12 (3), ISSN 1565-8996

- Frenken, Karen (2009), Irrigation in the Middle East Region in Figures. AQUASTAT Survey 2008, Water Reports, 34, Rome: FAO, ISBN 978-92-5-106316-3

- Garcia-Navarro, Lourdes (2009), Drought Reveals Iraqi Archaeological Treasures, NPR, retrieved 4 August 2010

- Geopolicity (2010), Managing the Tigris Euphrates Watershed (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2011, retrieved 20 December 2010

- Gray, J.E. (1864), "Revision of the species of Trionychidae found in Asia and Africa, with descriptions of some new species", Proceedings of the General Meetings for Scientific Business of the Zoological Society of London: 81–82

- Hartmann, R. (2010), "al- Furāt", in Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.), Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.), Leiden: Brill Online, OCLC 624382576

- Helbaek, Hans (1972), "Samarran Irrigation Agriculture at Choga Mami in Iraq", Iraq, 34 (1): 35–48, doi:10.2307/4199929, JSTOR 4199929

- Hillel, Daniel (1994), Rivers of Eden: the Struggle for Water and the Quest for Peace in the Middle East, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-508068-8

- Hole, F.; Zaitchik, B.F. (2007), "Policies, Plans, Practice, and Prospects: Irrigation in Northeastern Syria", Land Degradation & Development, 18 (2): 133–152, doi:10.1002/ldr.772

- Hritz, Carrie; Wilkinson, T.J. (2006), "Using Shuttle Radar Topography to Map Ancient Water Channels in Mesopotamia" (PDF), Antiquity, 80 (308): 415–424, doi:10.1017/S0003598X00093728, ISSN 0003-598X

- Iraqi Ministries of Environment, Water Resources and Municipalities and Public Works (2006a), "Volume I: Overview of Present Conditions and Current Use of the Water in the Marshlands Area/Book 1: Water Resources", New Eden Master Plan for Integrated Water Resources Management in the Marshlands Areas, New Eden Group

- Iraqi Ministries of Environment, Water Resources and Municipalities and Public Works (2006b), "Annex III: Main Water Control Structures (Dams and Water Diversions) and Reservoirs", New Eden Master Plan for Integrated Water Resources Management in the Marshlands Areas, New Eden Group

- Isaev, V.A.; Mikhailova, M.V. (2009), "The Hydrology, Evolution, and Hydrological Regime of the Mouth Area of the Shatt al-Arab River", Water Resources, 36 (4): 380–395, doi:10.1134/S0097807809040022

- Jamous, Bassam (2009), "Nouveaux Aménagements Hydrauliques sur le Moyen Euphrate Syrienne. Appel à Projets Archéologiques d'Urgence" (PDF), Studia Orontica (in French), DGAM, retrieved 14 December 2009

- Jawad, Laith A. (2003), "Impact of Environmental Change on the Freshwater Fish Fauna of Iraq", International Journal of Environmental Studies, 60 (6): 581–593, doi:10.1080/0020723032000087934

- Jongerden, Joost (2010), "Dams and Politics in Turkey: Utilizing Water, Developing Conflict", Middle East Policy, 17 (1): 137–143, doi:10.1111/j.1475-4967.2010.00432.x

- Kaya, Ibrahim (1998), "The Euphrates–Tigris Basin: An Overview and Opportunities for Cooperation under International Law", Arid Lands Newsletter, 44, ISSN 1092-5481

- Kliot, Nurit (1994), Water Resources and Conflict in the Middle East, Milton Park: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-09752-5

- Kolars, John (1994), "Problems of International River Management: The Case of the Euphrates", in Biswas, Asit K. (ed.), International Waters of the Middle East: From Euphrates-Tigris to Nile, Oxford University Press, pp. 44–94, ISBN 978-0-19-854862-1

- Kolars, John F.; Mitchell, William A. (1991), The Euphrates River and the Southeast Anatolia Development Project, Carbondale: SIU Press, ISBN 978-0-8093-1572-7

- Krouma, I. (2006), "National Aquaculture Sector Overview. Syrian Arab Republic. National Aquaculture Sector Overview Fact Sheets", FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department, FAO, retrieved 15 December 2009

- McClellan, Thomas L. (1997), "Euphrates Dams, Survey of", in Meyers, Eric M. (ed.), The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Ancient Near East, 2, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 290–292, ISBN 0-19-506512-3

- McDowall, David (2004), A Modern History of the Kurds, London: I.B. Tauris, ISBN 978-1-85043-416-0

- Moore, A.M.T.; Hillman, G.C.; Legge, A.J. (2000), Village on the Euphrates. From Foraging to Farming at Abu Hureyra, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-510807-8

- Muhesen, Sultan (2002), "The Earliest Paleolithic Occupation in Syria", in Akazawa, Takeru; Aoki, Kenichi; Bar-Yosef, Ofer (eds.), Neandertals and Modern Humans in Western Asia, New York: Kluwer, pp. 95–105, doi:10.1007/0-306-47153-1_7, ISBN 0-306-45924-8

- Muir, Jim (24 February 2009), "Iraq Marshes face Grave New Threat", BBC News, retrieved 9 August 2010

- Mutin, Georges (2003), "Le Tigre et l'Euphrate de la Discorde", VertigO (in French), 4 (3): 1–10, doi:10.4000/vertigo.3869

- Naval Intelligence Division (1944), Iraq and the Persian Gulf, Geographical Handbook Series, OCLC 1077604

- Negev, Avraham; Gibson, Shimon (2001), "Archaeological Encyclopedia of the Holy Land", Continuum, New York, ISBN 0-8264-1316-1

- O'Hara, Thomas (2004), "Coalition Celebrates Transfer of Power" (PDF), Essayons Forward, 1 (2): 3–4, OCLC 81262733, archived from the original (PDF) on 19 June 2009

- Oates, Joan (1960), "Ur and Eridu, the Prehistory", Iraq, 22: 32–50, doi:10.2307/4199667, JSTOR 4199667

- Partow, Hassan (2001), The Mesopotamian Marshlands: Demise of an Ecosystem (PDF), Nairobi: UNEP, ISBN 92-807-2069-4, archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2017, retrieved 10 August 2010

- Rahi, Khayyun A.; Halihan, Todd (2009), "Changes in the Salinity of the Euphrates River System in Iraq", Regional Environmental Change, 10: 27–35, doi:10.1007/s10113-009-0083-y

- Sagona, Antonio; Zimansky, Paul (2009), Ancient Turkey, Routledge World Archaeology, London: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-48123-6

- Sahan, Emel; Zogg, Andreas; Mason, Simon A.; Gilli, Adi (2001), Case-Study: Southeastern Anatolia Project in Turkey – GAP (PDF), Zürich, archived from the original (PDF) on 9 February 2005, retrieved 6 August 2010

- Schmid, P.; Rentzel, Ph.; Renault-Miskovsky, J.; Muhesen, Sultan; Morel, Ph.; Le Tensorer, Jean Marie; Jagher, R. (1997), "Découvertes de Restes Humains dans les Niveaux Acheuléens de Nadaouiyeh Aïn Askar (El Kowm, Syrie Centrale)" (PDF), Paléorient, 23 (1): 87–93, doi:10.3406/paleo.1997.4646

- Shahin, Mamdouh (2007), Water Resources and Hydrometeorology of the Arab Region, Dordrecht: Springer, Bibcode:2007wrha.book.....S, ISBN 978-1-4020-5414-3

- Shapland, Greg (1997), Rivers of Discord: International Water Disputes in the Middle East, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-312-16522-2

- Steele, Caroline (2005), "Who Has not Eaten Cherries with the Devil? Archaeology under Challenge", in Pollock, Susan; Bernbeck, Reinhard (eds.), Archaeologies of the Middle East: Critical Perspectives, Blackwell Studies in Global Archaeology, Malden: Blackwell, pp. 45–65, ISBN 0-631-23001-7

- Tanaka, Eisuke (2007), "Protecting one of the best Roman Mosaic Collections in the World: Ownership and Protection in the Case of the Roman Mosaics from Zeugma, Turkey" (PDF), Stanford Journal of Archaeology, 5: 183–202, OCLC 56070299

- Thomason, A.K. (2001), "Representations of the North Syrian Landscape in Neo-Assyrian Art", Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, 323 (323): 63–96, doi:10.2307/1357592, JSTOR 1357592

- Ur, Jason A.; Karsgaard, Philip; Oates, Joan (2007), "Early Urban Development in the Near East" (PDF), Science, 317 (5842): 1188, Bibcode:2007Sci...317.1188U, doi:10.1126/science.1138728, PMID 17761874

- van de Mieroop, Marc (2007), A History of the Ancient Near East, ca. 3000–323 BC, Blackwell History of the Ancient World (2nd ed.), Malden: Blackwell, ISBN 978-1-4051-4911-2

- Woods, Christopher (2005), "On the Euphrates", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie, 95 (1–2): 7–45, doi:10.1515/zava.2005.95.1-2.7

- Zarins, Juris (1997), "Euphrates", in Meyers, Eric M. (ed.), The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Ancient Near East, 2, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 287–290, ISBN 0-19-506512-3

External links