Tell Mashnaqa

Tell Mashnaqa (Arabic: تل مشنقة) is an archaeological site located on the Khabur River, a tributary to the Euphrates, about 30 kilometres (19 mi) south of Al-Hasakah in northeastern Syria. The earliest occupation of the site dates to the Ubaid period (ca. 5200–4900 BC), and was excavated by a Danish team from 1990–1995 in four seasons.[1]

تل مشنقة | |

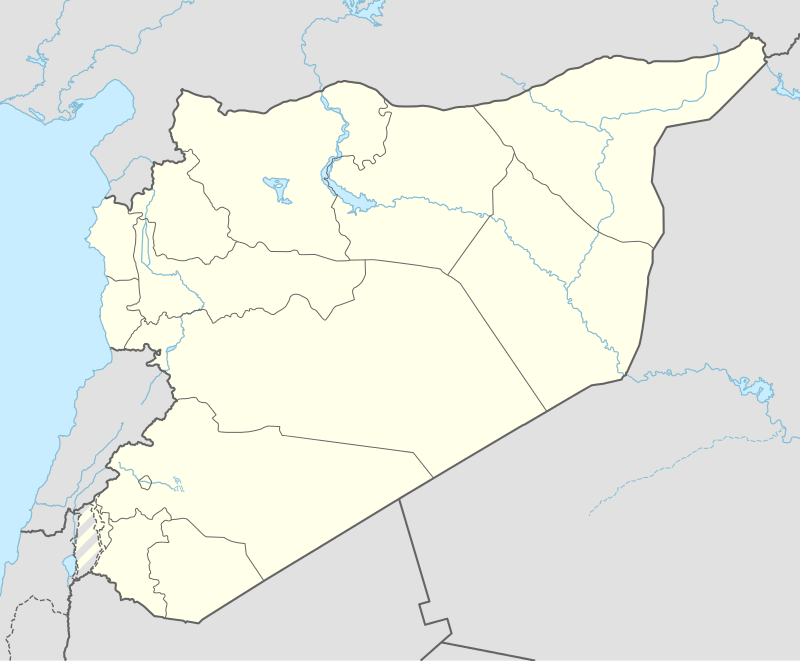

Shown within Syria | |

| Location | 30 km south of Al-Hasakah, Syria |

|---|---|

| Region | Khabur River region |

| Coordinates | 36.288425°N 40.79464°E |

| Type | settlement |

| Area | 4 hectares (0.015 sq mi) |

| Height | 4–11 m |

| History | |

| Material | mudbrick |

| Founded | ca. 5200 |

| Abandoned | ca. 2000 BC |

| Periods | Pottery Neolithic, Ubaid period, Uruk, Early Bronze Age |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1990—1995 |

| Condition | ruins |

| Ownership | Public |

Overview

The tell, now flooded by the al-Hassakah Dam project, was around 4 hectares (0.015 sq mi) in area. The western side of the tell formed a high mound, rising to a height of more than 11 metres (36 ft). The lower and flatter eastern side rose 4 metres (13 ft) above plain level.[1]

The mudbrick houses, found at the earliest level of the tell, had small rooms with fireplaces, grinding stones, mortars and painted pots. The later levels show a shift in occupation to other parts of the tell, where areas inhabited earlier were turned into a refuse midden and later a cemetery. The site was later abandoned for hundreds of years only to be rebuilt again in the fourth millennium BC. This level had a large tripartite building measuring about 11.5 by 10.5 m.[2]

Boat models

One of the most remarkable finds at the Ubaid level of the site were fragments of two pottery boat models, excavated in 1991.[2] The models represented long, narrow canoes with pointed sterns. The boats were probably made of reed coated with bitumen to make them waterproof. The findings strongly suggest that people of the Khabur region had already made use of boats for transport and fishing by c. 5000 BC, if not before.[2] Similar models have been unearthed from other Ubaid sites such as Eridu, Ubaid, Uqair and Abada.[2]

References

- Thuesen, Ingolf (1996), Sultan, Muhesen (ed.), Tell Mashnaqa: Danish Mission, Institut Français d’Etudes Arabes de Damas, pp. 47–53

- Akkermans, Peter M. M. G.; Schwartz, Glenn M. (2003). The Archaeology of Syria: From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (c. 16,000–300 BC). Cambridge University Press. pp. 167–168. ISBN 0-521-79666-0.