Bateleur

The Bateleur (Terathopius ecaudatus) is a medium-sized eagle in the family Accipitridae. Its closest relatives are the snake eagles. It is the only member of the genus Terathopius and may be the origin of the "Zimbabwe Bird", the national emblem of Zimbabwe.[2] It is endemic to Africa and small parts of Arabia. "Bateleur" is French for "street performer".[3]

| Bateleur | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male at Maasai Mara with a coqui francolin kill | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Accipitriformes |

| Family: | Accipitridae |

| Genus: | Terathopius Lesson, 1830 |

| Species: | T. ecaudatus |

| Binomial name | |

| Terathopius ecaudatus (Daudin, 1800) | |

| |

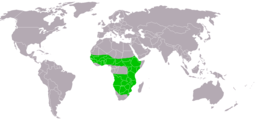

| approximate breeding range | |

Description

The average adult is 55 to 70 cm (22 to 28 in) long with a 186 cm (6 ft 1 in) wingspan. The wing chord averages approximately 51 cm (20 in). Adult weight is typically 2 to 2.6 kg (4 lb 7 oz to 5 lb 12 oz).[4]

The Bateleur is a colourful species with a bushy head and very short tail (ecaudatus is Latin for tail-less) which, together with its white underwing coverts, makes it unmistakable in flight. The tail is so small the bird's legs protrude slightly beyond the tail during flight. The Bateleur is sexually dimorphic; both adults have black plumage, a chestnut mantle and tail, grey shoulders, tawny wing coverts, and red facial skin, bill and legs. The female additionally has tawny secondary wing feathers. Less commonly, the mantle may be white.[5] Immature birds are brown with white dappling and have greenish blue-grey facial skin.[6] It takes them seven or eight years to reach full maturity.

Distribution and habitat

The range of the Bateleur spreads across Mauritania, Senegal, Mali, Guinea, Sudan, Ethiopia, Somalia, Namibia, Botswana, South Africa, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Côte d'Ivoire, Kenya, Nigeria, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Tanzania.[6] The bird's range has diminished significantly in recent decades, possibly due to poisoning,[7] and as such has been confined mostly to conservation areas such as national wildlife parks.[8]

In April 2012, a juvenile Bateleur was seen in Algeciras in southern Spain.[9] This was the first European record for the Bateleur.

Ecology

This eagle is a solitary, tree-nesting species with a large home range.[10]

Habitat

The Bateleur is a common to fairly common resident or nomadic[6] bird of the open savanna country and woodland (thornveld) within Sub-Saharan Africa; it also occurs in south-western Arabia. Found in closed-canopy savannah woodland habitats, including Acacia savannah, Mopane and miombo woodlands. It is commonest in broad-leaved woodland in the Okavango Delta. It occurs rarely in heavily forested, mountainous or largely treeless habitats. In Namibia, it is often found over tall woodland near drainage lines, and ephemeral rivers in north-eastern Namibia and within the more arid Etosha National Park.[10]

Diet

The Bateleur is diurnal, foraging over a huge range (55–200 km²)[6] and hunting over a territory of approximately 250 square miles (650 km2) a day. Bateleurs are hunters and scavengers, they will attack other species for food and will scavenge carrion. The bird is adept at finding smaller carcasses before most other scavengers. The Bateleur will hunt birds and their eggs (mainly doves and pigeons), small reptiles, small mammals (like rodents, genets and mongooses) and insects.[10][6] Its prey is often stolen by the tawny eagle (Aquila rapax), and the Bateleur may attempt kleptoparasitism of white-backed vultures.[8]

Behaviour

The Bateleur is generally silent, but can produce a variety of barks and screams. The bird spends a considerable amount of time on the wing, particularly in low-altitude glides.[11] "Bateleur" is French for "tumbler". This name implies the bird's characteristic habit of rocking its wings or tilting action from side to side when gliding, as if catching its balance.[6] The wings are held in a slightly bent, deep 'V', position and fast flight with. Bateleurs hunt from swift, direct gliding flight across country, or in wide sweeping circles.[12] The Bateleur is a territorial bird and will defend its territory by means of an aggressive attack flight pattern shown to intruding conspecifics.[13] Intruders to whom this behavior is displayed always submit and submission is shown by retreating to a safe upper boundary (elevation). Males and females both display this behavior in all stages of the breeding cycle. This behavior is mainly shown to members of the same sex and particularly to non-adults, as it is thought that they may have a greater ability to take over another bird's territory (having greater competitive ability for limited food resources).[13] In the wild Bateleurs are shy of man and sensitive to disturbance at the nest, easily abandoning the structure.[14] In captivity, however, they becomes unusually tame.[15] Bateleur eagles are among a group of raptors that secrete a clear, salty fluid from their nares whilst eating. According to Schmidt-Nielson's (1964) hypothesis, this is due to the general necessity for birds to use an extrarenal mechanism of salt secretion to aid water reabsorption.[16]

Sunning

_male_(6854281398).jpg)

Bateleurs frequently enter water-bodies for a bath and then open their wings to often sunbathe. Standing upright and holding their wings straight out to the sides and tipped vertically, a classic 'phoenix' pose as they turn to follow the sun.[17] Bateleurs will lie on the ground with their wings spread, exposing the feathers to direct sunlight, warming the oils in the feathers. The bird will then spread the oils with its beak to improve its aerodynamics. Bateleurs may also be seen "praying" allowing ants to crawl over the wings and feathers, collecting bits of food, dead feather and skin material. When covered in ants, the Bateleur then ruffles its feathers, startling the ants, which react by secreting formic acid as self-defense. This in turn kills the ticks and fleas, ridding the host of its parasites.[18]

Breeding

Bateleurs are monogamous and breed from September–May in West Africa, throughout the year in East Africa and December–August in southern Africa, with a peak from January to April.[6][10] Bateleurs are long-lived species, slow-maturing, slow-breeding species,[10] laying only one egg at a time[19] (this is because more parental care can be invested per offspring resulting in greater survival).[8] Nests are stick platforms placed below the canopy of large trees such as Senegalia nigrescens.[14] Both parents put equal amounts of care into the young and breeding failures are due to predation or a failure to lay the egg. Incubation lasts for 55 days and annual mean production is 0.47 chicks per breeding pair per year.[19]

Conservation

The Bateleur is considered to have a lifespan about 27 years. The annual adult survival rate is estimated at 95%, while the annual juvenile survival rate is estimated at 75%. Average sex ratios remain 1:1.[8] Global population is estimated in the tens of thousands at 10,000 to 100,000 individuals.[20][6] Like the martial eagle, the Bateleur is reasonably common in conservation areas and scarce elsewhere.[8] In 2009, the Bateleur was placed in the near threatened IUCN Red List category due to loss of habitat, pesticides, capture for international trade and nest disturbance.[6][20] Decline of the species and the reduction in range is suspected to have been moderately rapid over the past three generations. In South Africa and Namibia the Bateleur has been labelled as a "Vulnerable/Endangered" species, most likely from being trapped, for its feathers to be used in medicine by traditional healers for predicting future events.[10] The population has also decreased due to it feasting on poisoned animal carcasses being left out for other species. The Bateleur's wide foraging areas and their ability to locate very small pieces of carrion, makes them highly susceptible to poison-laced carcasses even from a small proportion of farmers who use poisons.[10] No large scale actions are underway but they are possibly protected in Yemen as an endangered species.[6] It is proposed to implement education and awareness campaigns across its range to reduce the use of poisoned baits. Regular population monitoring is being carried out.[21]

Media

Adult

Adult male

A female sunwarming in a zoo

Immature

Female in Texas

Two juveniles in Botswana

Female drinking  Skeleton of a bateleur eagle (Museum of Osteology)

Skeleton of a bateleur eagle (Museum of Osteology)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Terathopius ecaudatus. |

References

- BirdLife International (2012). "Terathopius ecaudatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Zimbabwe Bird". victoriafalls-guide.net.

- "bateleur translation English - French dictionary - Reverso". reverso.net.

- J. M. Mendelsohn, A. C. Kemp, H. C. Biggs, R. Biggs & C. J. Brown(1989) WING AREAS, WING LOADINGS AND WING SPANS OF 66 SPECIES OF AFRICAN RAPTORS Ostrich, Vol. 60, No.1, p.35-60

- Newman, K (1998) Newman's Birds of Southern Africa. Halfway House: Southern Book Publishers. ISBN 1868127680.

- BirdLife International (2019) Species factsheet: Terathopius ecaudatus. Downloaded fromhttp://www.birdlife.org on 29/07/2019.

- Allan, D. 1996. A Photographic Guide to Birds of Prey of Southern, Central and East Africa. Cape Town: New Holland Publishers. ISBN 1853689033.

- Hockey, P.A.R.; Dean, W.R.J. and Ryan, P.G. 2016. Roberts VII Birds of Southern Africa. John Voelcker Book Fund.

- http://birdcadiz.com/terathopius-ecaudatus-aguila-volatinera-bateleur-1

- Simmons, R. E., and C. J. Brown. "Bateleur Terathopius ecaudatus." The Atlas of Southern African Birds 1 (1997): 202-203.

- Kemp, AC & Begg KS 2001. Comparison of time-activity budgets and population structure for 18 large-bird species in the Kruger National Park, South Africa. Ostrich, Vol.72, No.3-4, p.179-184

- Steyn, Peter. "Some observations on the bateleur Terathopius ecaudatus (Daudin)." Ostrich 36, no. 4 (1965): 203-213.

- Watson, R.T. (1989). Aggressive display and territoriality of the bateleur Terathopius ecaudatus. African Zoology, 24(2),p146-150.

- Chittenden, Hugh (2016). Roberts bird guide : illustrating nearly 1,000 species in Southern Africa. Davies, Greg (Ornithologist),, Weiersbye, Ingrid,, John Voelcker Bird Book Fund., Percy FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology (Cape Town, South Africa) (Second ed.). Cape Town. ISBN 9781920602017. OCLC 958354485.

- Moreau, R. E. "On the Bateleur, especially at the Nest." Ibis87, no. 2 (1945): 224-249.

- Cade, T.J. and L. Greenwald 1964. Nasal Salt Secretion in Falconiform Birds. The Condor, Vol.68, No.4, p.338-350

- "Bataleur Eagle | Terathopius ecaudatus | Africa..." www.krugerpark.co.za. Retrieved 2019-07-29.

- Africa, HPH Publishing South. "Praying Bateleur? Do you know why Bateleur Eagles do this?". HPH Publishing South Africa. Retrieved 2019-07-29.

- Watson, R.T. (1990) BREEDING BIOLOGY OF THE BATELEUR. Ostrich, 61:1-2, p13-23. DOI: 10.1080/00306525.1990.9633933.

- Ferguson-Lees, J. and Christie, D. A. (2001) Raptors of the world. London: Christopher Helm.

- "The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 2019-07-29.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Terathopius ecaudatus. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Terathopius ecaudatus |