Southern white rhinoceros

The southern white rhinoceros or southern square-lipped rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum simum), is one of the two subspecies of the white rhinoceros (the other being the much rarer Northern white rhinoceros). It is the most common and widespread subspecies of rhinoceros.

| Southern white rhinoceros | |

|---|---|

| A southern white rhinoceros in Pilanesberg National Park, South Africa | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Rhinocerotidae |

| Genus: | Ceratotherium |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | C. s. simum |

| Trinomial name | |

| Ceratotherium simum simum (Burchell, 1817) | |

| |

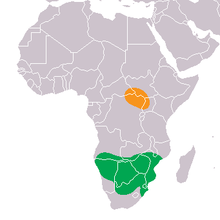

| Range map in green | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

As of late December 2007, the total population was estimated at 17,460 southern white rhino in the wild, making them by far the most abundant subspecies of rhino in the world. South Africa is the stronghold for this subspecies (93.0%), conserving 16,255 individuals in the wild in 2007. The current census from Save the Rhino's official website revealed there are 19,682–21,077 southern white rhinoceros since 2015.[2]

Taxonomic and evolutionary history

The southern white rhinoceros is the nominate subspecies, which was given the scientific name Ceratotherium simum simum by the English explorer William John Burchell in the 1810s. Other names were also proposed for the southern subspecies. The subspecies is also known as Burchell's rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum burchellii) after William John Burchell and Oswell's rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum oswellii) after William Cotton Oswell respectively. However, they are considered as synonyms to its original scientific name.

Ceratotherium simum kiaboaba (or Rhinoceros kiaboaba), also known as straight-horned rhinoceros, was proposed as a different variety found near Lake Ngami and north of the Kalahari desert. However, it was discovered to be an actual southern white rhinoceros.

Following the phylogenetic species concept, recent research in 2010 has suggested the southern and northern white rhinoceros may be different species, rather than subspecies of white rhinos, in which case the correct scientific name for the northern subspecies is Ceratotherium cottoni and the southern subspecies should be known as simply Ceratotherium simum. Distinct morphological and genetic differences suggest the two proposed species have been separated for at least a million years.[3]

Physical descriptions

The southern white rhinoceros is one of largest and heaviest land animals in the world. It has an immense body and large head, a short neck and broad chest. Females weigh 1,700 kg (3,750 lb) and males 2,300 kg (5,070 lb).[4] The head-and-body length is 3.4–4 m (11.2–13.1 ft) and a shoulder height of 160–186 cm (5.25–6.10 ft).[4] On its snout it has two horns. The front horn is larger than the other horn and averages 60 cm (24 in) in length and can reach 150 cm (59 in).[5] Females usually have longer but thinner horns than the males which is larger but shorter. The southern white rhinoceros also has a prominent muscular hump that supports its relatively large head. The colour of this animal can range from yellowish brown to slate grey. Most of its body hair is found on the ear fringes and tail bristles, with the rest distributed rather sparsely over the rest of the body. Southern white rhinos have the distinctive flat broad mouth that is used for grazing.

Habitat and distribution

The southern white rhino live in the grasslands and savannahs of southern Africa, ranging from South Africa to Zambia. About 98.5% of southern white rhino occur in just five countries (South Africa, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Kenya and Uganda). The southern white rhino was nearly extinct with just less than 20 individuals in a single South African reserve in early 20th century. The small population of white rhinoceros has slowly recovered during the years, having grown to 840 individuals back in 1960s to 1,000 in the 1980s. White rhino trophy hunting was legalized and regulated in 1968, and after initial miscalculations is now generally seen to have assisted in the species' recovery by providing incentives for landowners to boost rhino populations.[6]

Almost at the edge of extinction in the 20th century, the southern white rhinoceros has made a tremendous comeback. In 2001, it was estimated that there were 11,670 white rhinos in the wild of southern Africa with a further 777 individuals in captivity worldwide, making it the most common rhinoceros in the world. By the end of 2007, wild-living southern white rhino had increased to an estimated 17,480 animals. In 2015, there are an estimated population of 19,682–21,077 wild southern white rhinoceros.[2]

Threats

The southern white rhinoceros is listed as Near Threatened, though it is mostly threatened by habitat loss, continuous poaching in recent years and the high illegal demand for rhino horn for commercial purposes and use in traditional Chinese medicine.[1]

Conservation status

Introduction/reintroduction projects

There are smaller reintroduced populations within the historical range of the southern white rhinoceros in Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Swaziland, Zambia and in southwestern Democratic Republic of the Congo, while a small population survives in Mozambique. Populations have also been introduced outside of the former range of the species to Kenya, Uganda and Zambia, where their northernmost relatives used to occur.[7] The southern white rhinoceros have been reintroduced in the Ziwa Rhino Sanctuary in Uganda,[8] and in the Lake Nakuru National Park and the Kigio Wildlife Conservancy in Kenya.

In 2010, nine southern white rhinoceros were imported from South Africa and shipped to the Yunnan province from southeast China where they were kept in an animal wildlife park for acclimation. In March 2013, seven of the animals were shipped to the Laiyanghe National Forest Park, a habitat where Sumatran and Javan rhinoceros once lived.[9] Two of the southern white rhinos began the process of being released into the wild on May 13, 2014.[10]

In captivity

Wild-caught southern white rhinoceros will readily breed in captivity given appropriate amounts of space and food, as well as the presence of other female rhinos of breeding age. Many rhinoceros that live in zoos today are a part of a cooperative breeding program to increase population numbers and maintain genetic diversity without pulling individuals from the wild.[11] For instance, 96 calves have been born at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park since 1972. However, the rate of reproduction is fairly low among captive-born southern white females, potentially due to their diet. Ongoing research through San Diego Zoo Global is hoping to not only focus on this, but also on identifying other captive species that are possibly affected and developing new diets and feeding practices aimed at enhancing fertility.[12] In South Africa a population of southern white rhinos are being raised on farms and ranches for their horns along with the black rhino.[13]

References

- Emslie, R. (2011). "Ceratotherium simum ssp. simum". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved 16 May 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Rhino population figures". SaveTheRhino.org. 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- Groves, C.P.; Fernando, P; Robovský, J (2010). "The Sixth Rhino: A Taxonomic Re-Assessment of the Critically Endangered Northern White Rhinoceros". PLoS ONE. 5 (4): e9703. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...5.9703G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009703. PMC 2850923. PMID 20383328.

- Macdonald, D. (2001). The New Encyclopedia of Mammals. Oxford University Press, Oxford. ISBN 0198508239.

- Heller, E. (1913). "The white rhinoceros". Smithsonian Misc. Coll. 61 (1).

- Michael 't Sas-Rolfes. "Saving African Rhinos: A Market Success Story" (PDF). Retrieved 27 September 2015. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Emslie, R. & Brooks, M. (1999). African Rhino. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. IUCN/SSC African Rhino Specialist Group. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK. ISBN 2-8317-0502-9.

- Lutalo, Eric (14 May 2017). "Ziwa sanctuary where rhinos have a lease of life". www.rhinofund.org. Retrieved 2019-05-15.

- Patrick Scally, "Rhinos reintroduced to Yunnan" GoKunming.com 2013-04-02

- (Chinese) 13、中央电视台新闻频道-[新闻直播间]云南普洱:白犀牛今天进行 2014-05-13

- Association of Zoos and Aquariums (2017). "Species Survival Plans".

- San Diego Zoo Global Public Relations (2017). "Rhino Born Thanks to Science".

- "Can farming rhinos for their horns save the species?". The Daily Telegraph. November 11, 2017. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Ceratotherium simum simum |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Southern white rhinoceros. |