Harvest festival

A harvest festival is an annual celebration that occurs around the time of the main harvest of a given region. Given the differences in climate and crops around the world, harvest festivals can be found at various times at different places. Harvest festivals typically feature feasting, both family and public, with foods that are drawn from crops that come to maturity around the time of the festival. Ample food and freedom from the necessity to work in the fields are two central features of harvest festivals: eating, merriment, contests, music and romance are common features of harvest festivals around the world.

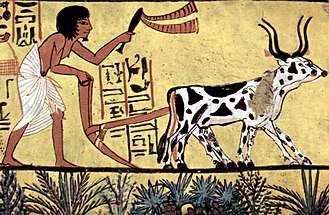

| Agriculture |

|---|

|

|

Categories

|

|

|

In North America, Canada and the US each have their own Thanksgiving celebrations in October and November.

In Britain, thanks have been given for successful harvests since pagan times. Harvest festival is traditionally held on the Sunday near or of the Harvest Moon. This is the full Moon that occurs closest to the autumn equinox (22 or 23 September). The celebrations on this day usually include singing hymns, praying, and decorating churches with baskets of fruit and food in the festival known as Harvest Festival, Harvest Home, Harvest Thanksgiving or Harvest Festival of Thanksgiving.

In British and English-Caribbean churches, chapels and schools, and some Canadian churches, people bring in produce from the garden, the allotment or farm. The food is often distributed among the poor and senior citizens of the local community, or used to raise funds for the church, or charity.

Harvest festivals in Asia include the Chinese Mid-Autumn Festival (中秋節), one of the most widely spread harvest festivals in the world. In Iran Mehrgan was celebrated in an extravagant style at Persepolis. Not only was it the time for harvest, but it was also the time when the taxes were collected. Visitors from different parts of the Persian Empire brought gifts for the king, all contributing to a lively festival. In India, Makar Sankranti, Thai Pongal, Uttarayana, Lohri, and Magh Bihu or Bhogali Bihu in January, Holi in February–March, Vaisakhi in April and Onam in August–September are a few important harvest festivals.

Jews celebrate the week-long harvest festival of Sukkot in the autumn. Observant Jews build a temporary hut or shack called a sukkah, and spend the week living, eating, sleeping, and praying inside it. A sukkah has three walls and a semi-open roof, designed to allow the elements to enter. It is reminiscent of the tabernacles Israelite farmers would live in during the harvest, at the end of which they would bring a portion of the harvest to the Temple in Jerusalem.

Customs and traditions

An early harvest festival used to be celebrated at the beginning of the harvest season on 1 August and was called Lammas, meaning 'loaf Mass'. The Latin prayer to hallow the bread is given in the Durham Ritual. Farmers made loaves of bread from the fresh wheat crop. These were given to the local church as the Communion bread during a special service thanking God for the harvest.

By the sixteenth century a number of customs seem to have been firmly established around the gathering of the final harvest. They include the reapers accompanying a fully laden cart; a tradition of shouting "Hooky, hooky"; and one of the foremost reapers dressing extravagantly, acting as 'lord' of the harvest and asking for money from the onlookers. A play by Thomas Nashe, Summer's Last Will and Testament, (first published in London in 1600 but believed from internal evidence to have been first performed in October 1592 at Croydon) contains a scene which demonstrates several of these features. There is a character personifying harvest who comes on stage attended by men dressed as reapers; he refers to himself as their "master" and ends the scene by begging the audience for a "largesse". The scene is clearly inspired by contemporary harvest celebrations, and singing and drinking feature largely. The stage instruction reads:

"Enter Haruest with a sythe on his neck, & all his reapers with siccles, and a great black bowle with a posset in it borne before him: they come in singing."

The song which follows may be an actual harvest song, or a creation of the author's intended to represent a typical harvest song of the time:

Merry, merry, merry, cheary, cheary, cheary,

Trowle the black bowl to me ;

Hey derry, derry, with a poupe and a lerry,

Ile trowle it again to the:

Hooky, hooky, we have shorn,

And we have bound,

And we have brought Harvest

Home to town.

The shout of "hooky, hooky" appears to be one traditionally associated with the harvest celebration. The last verse is repeated in full after the character Harvest remarks to the audience "Is your throat cleare to helpe us sing hooky, hooky?" and a stage direction adds, "Heere they all sing after him". Also, in 1555 in Archbishop Parker's translation of Psalm 126 occur the lines:

"He home returnes: wyth hocky cry,

With sheaues full lade abundantly."

In some parts of England "Hoakey" or "Horkey" (the word is spelled variously) became the accepted name of the actual festival itself:

"Hoacky is brought Home with hallowing

Boys with plum-cake The Cart following".

Another widespread tradition was the distribution of a special cake to the celebrating farmworkers. A prose work of 1613 refers to the practice as predating the Reformation. Describing the character of a typical farmer, it says:

"Rocke Munday..Christmas Eve, the hoky, or seed cake, these he yeerely keepes, yet holds them no reliques of popery."[1]

Early English settlers took the idea of harvest thanksgiving to North America. The most famous one is the harvest Thanksgiving held by the Pilgrims in 1621.

.jpg)

Nowadays the festival is held at the end of harvest, which varies in different parts of Britain. Sometimes neighbouring churches will set the Harvest Festival on different Sundays so that people can attend each other's thanksgivings.

Until the 20th century most farmers celebrated the end of the harvest with a big meal called the harvest supper, to which all who had helped in the harvest were invited. It was sometimes known as a "Mell-supper", after the last patch of corn or wheat standing in the fields which was known as the "Mell" or "Neck". Cutting it signified the end of the work of harvest and the beginning of the feast. There seems to have been a feeling that it was bad luck to be the person to cut the last stand of corn. The farmer and his workers would race against the harvesters on other farms to be first to complete the harvest, shouting to announce they had finished. In some counties the last stand of corn would be cut by the workers throwing their sickles at it until it was all down, in others the reapers would take it in turns to be blindfolded and sweep a scythe to and fro until all of the Mell was cut down.

Some churches and villages still have a Harvest Supper. The modern British tradition of celebrating Harvest Festival in churches began in 1843, when the Reverend Robert Hawker invited parishioners to a special thanksgiving service at his church at Morwenstow in Cornwall. Victorian hymns such as We plough the fields and scatter, Come, ye thankful people, come and All things bright and beautiful but also Dutch and German harvest hymns in translation helped popularise his idea of harvest festival, and spread the annual custom of decorating churches with home-grown produce for the Harvest Festival service. On 8 September 1854 the Revd Dr William Beal, Rector of Brooke, Norfolk,[2] held a Harvest Festival aimed at ending what he saw as disgraceful scenes at the end of harvest, and went on to promote 'harvest homes' in other Norfolk villages. Another early adopter of the custom as an organised part of the Church of England calendar was Rev Piers Claughton at Elton, Huntingdonshire in or about 1854.[3]

As British people have come to rely less heavily on home-grown produce, there has been a shift in emphasis in many Harvest Festival celebrations. Increasingly, churches have linked Harvest with an awareness of and concern for people in the developing world for whom growing crops of sufficient quality and quantity remains a struggle. Development and Relief organisations often produce resources for use in churches at harvest time which promote their own concerns for those in need across the globe.

In the early days, there were ceremonies and rituals at the beginning as well as at the end of the harvest.

Encyclopædia Britannica traces the origins to "the animistic belief in the corn [grain] spirit or corn mother." In some regions the farmers believed that a spirit resided in the last sheaf of grain to be harvested. To chase out the spirit, they beat the grain to the ground. Elsewhere they wove some blades of the cereal into a "corn dolly" that they kept safe for "luck" until seed-sowing the following year. Then they plowed the ears of grain back into the soil in hopes that this would bless the new crop.

- Church bells could be heard on each day of the harvest.

- A corn dolly was made from the last sheaf of corn harvested. The corn dolly often had a place of honour at the banquet table, and was kept until the following spring.

- In Cornwall, the ceremony of Crying The Neck was practiced. Today it is still re-enacted annually by The Old Cornwall Society.

- The horse bringing the last cart load was decorated with garlands of flowers and colourful ribbons.

- A magnificent Harvest feast was held at the farmer's house and games played to celebrate the end of the harvest.

See also

- List of global Harvest Festivals

- Thanksgiving

- Dozhinki

- Mid-Autumn Festival

- Nabanna

- Niiname-no-Matsuri

Notes

References

- Overbury, Thomas Characters: the Franklin, London, 1613

- Dictionary of National Biography

- Burn-Murdoch, Bob (1996). What's So Special About Huntingdonshire?. St Ives: Friends of the Norris Museum. p. 24. ISBN 0-9525900-1-8.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article about harvest festivals. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Harvest festivals. |