The Leisure Hour

The Leisure Hour was a British general-interest periodical of the Victorian era which ran weekly from 1852 to 1905.[1][2] It was the most successful of several popular magazines published by the Religious Tract Society, which produced Christian literature for a wide audience.[1] Each issue mixed multiple genres of fiction and factual stories, historical and topical.[1]

The cover of issue 1032, with an illustration accompanying a story about a shipwreck. | |

| Frequency | Weekly |

|---|---|

| Publisher | Religious Tract Society |

| First issue | January 1, 1852 |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Based in | London |

| Language | English |

| OCLC | 362165421 |

The magazine's title referred to campaigns that had decreased work hours, giving workers extra leisure time.[3] Until 1876, it carried the subtitle "A Family Journal of Instruction and Recreation";[4] after that, the subtitle changed to "An illustrated magazine for home reading".[5]

Each issue cost one penny and comprised 16 pages.[6] The layout typically included approximately six long articles, formatted in two columns per page, and five or six illustrations. The articles were a mix, including biographies, poetry, essays, and fiction. Each issue usually started with a piece of serialised fiction.[6]

The creation of the magazine was partly a response to non-religious popular magazines that the Religious Tract Society saw as delivering a "pernicious" morality to the working classes.[1] The ethos of the magazine was guided by Sabbatarianism: the campaign to keep Sunday as a day of rest.[4] It aimed to treat its diverse subjects "in the light of Christian truth".[4] Despite this, The Leisure Hour carried far fewer statements of Christian doctrine than the Society's other publications.[6] Compared to other popular magazines of the time, The Leisure Hour had a greater emphasis on fiction.[7]

Two days before the magazine's launch in 1852, a warehouse fire destroyed the first batch of The Leisure Hour, so replacement copies had to be printed.[3]

The magazine was edited by William Haig Miller until 1858,[5] James Macaulay from 1858 to 1895,[8] and William Stevens from 1895 to 1900.[5] Harold Copping was one of its illustrators.[9] Authors were initially only credited by initials rather than by name, giving the writing a collective rather than individual authority, though naming of authors became more common from the 1870s onwards.[1] In its jubilee issue, published in 1902, the magazine identified 111 authors who had contributed.[1]

Notable contributors

Gallery of illustrations

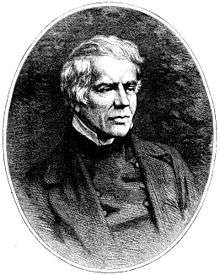

John Keble, 1867

John Keble, 1867 Mary Somerville, 1871

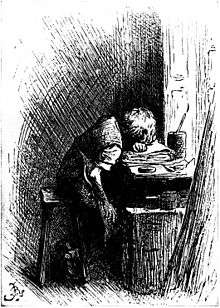

Mary Somerville, 1871 Charles Dickens, 1904

Charles Dickens, 1904 “A Vision of the Future. An aërial motor-car”, 1905

“A Vision of the Future. An aërial motor-car”, 1905

References

- Lechner, Doris (2013). "Serializing the Past in and out of the Leisure Hour: Historical Culture and the Negotiation of Media Boundaries". Mémoires du livre. 4 (2). doi:10.7202/1016740ar.

- Dozier, Graham (25 September 2014). A Gunner in Lee's Army: The Civil War Letters of Thomas Henry Carter. University of North Carolina Press. p. 290. ISBN 978-1-4696-1875-3.

- Louise Henson (2004). Culture and Science in the Nineteenth-century Media. Ashgate. pp. 75–77. ISBN 978-0-7546-3574-1.

- Stephanie Olsen (16 January 2014). Juvenile Nation: Youth, Emotions and the Making of the Modern British Citizen, 1880-1914. A&C Black. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-4725-1009-9.

- Worldcat entry for The leisure hour

- "Noakes, Richard (2004). "The Boy's Own Paper and late-Victorian juvenile magazines". In Geoffrey Cantor (ed.). Science in the nineteenth-century periodical: reading the magazine of nature (1. publ. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521836371. via Open Research Exeter http://hdl.handle.net/10036/31895

- Brian E. Maidment "Magazines of Popular Progress & the Artisans" Victorian Periodicals Review, Vol. 17, No. 3 (Fall, 1984), pp. 83-94. Johns Hopkins University Press on behalf of the Research Society for Victorian Periodicals. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20082117 Accessed: 13 November 2015

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1912). . Dictionary of National Biography (2nd supplement). 2. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- "Harold Copping". Spartacus Educational. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

Further reading

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Leisure Hour. |

- Palmegiano, E. M. (15 October 2013). Perceptions of the Press in Nineteenth-Century British Periodicals: A Bibliography. Anthem Press. pp. 329–352. ISBN 978-1-78308-053-3.