Earl

An earl (/ɜːrl/)[1] is a member of the nobility. The title originates in the Old English word eorl, meaning "a man of noble birth or rank."[2] The word is cognate with the Scandinavian form jarl, and meant "chieftain", particularly a chieftain set to rule a territory in a king's stead. In Scandinavia, it became obsolete in the Middle Ages and was replaced by duke (hertig/hertug/hertog). After the Norman Conquest, it became the equivalent of the continental count (in England in the earlier period, it was more akin to a duke; in Scotland it assimilated the concept of mormaer). However, earlier in Scandinavia, jarl could also mean a sovereign prince. For example, the rulers of several of the petty kingdoms of Norway had the title of jarl and in many cases they had no less power than their neighbours who had the title of king. Alternative names for the rank equivalent to "earl/count" in the nobility structure are used in other countries, such as the hakushaku (伯爵) of the post-restoration Japanese Imperial era.

In modern Britain, an earl is a member of the peerage, ranking below a marquess and above a viscount.[3] A feminine form of earl never developed; instead, countess is used.

Etymology

The term earl has been compared to the name of the Heruli, and to runic erilaz.[4] Proto-Norse eril, or the later Old Norse jarl, came to signify the rank of a leader.[5]

In Anglo-Saxon Britain, the term Ealdorman was used for men who held the highest political rank below King. Over time the Danish eorl became substituted for Ealdorman, which evolved into the modern form of the name.

The Norman-derived equivalent count (from Latin comes) was not introduced following the Norman conquest of England though countess was and is used for the female title. Geoffrey Hughes writes, "It is a likely speculation that the Norman French title 'Count' was abandoned in England in favour of the Germanic 'Earl' […] precisely because of the uncomfortable phonetic proximity to cunt".[6]

In the other languages of Britain and Ireland, the term is translated as: Welsh iarll, Irish and Scottish Gaelic iarla, Scots yarl or yerl, Cornish yurl.

Earls in the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth

|

| Part of a series on |

| Peerage |

|---|

|

Types |

|

Divisions |

|

History |

| House of Lords |

|

Forms of address

An earl has the title Earl of [X] when the title originates from a placename, or Earl [X] when the title comes from a surname. In either case, he is referred to as Lord [X], and his wife as Lady [X]. A countess who holds an earldom in her own right also uses Lady [X], but her husband does not have a title (unless he has one in his own right).

The eldest son of an earl, though not himself a peer, is entitled to use a courtesy title, usually the highest of his father's lesser titles (if any), for instance the eldest son of The Earl of Wessex is styled as James, Viscount Severn. The eldest son of the eldest son of an earl is entitled to use one of his grandfather's lesser titles, normally the second highest of the lesser titles. Younger sons are styled The Honourable [Forename] [Surname], and daughters, The Lady [Forename] [Surname] (Lady Diana Spencer being a well-known example).

There is no difference between the courtesy titles given to the children of earls and the children of countesses in their own right, provided the husband of the countess has a lower rank than she does. If her husband has a higher rank, their children will be given titles according to his rank.

In the peerage of Scotland, when there are no courtesy titles involved, the heir to an earldom, and indeed any level of peerage, is styled Master of [X], and successive sons as The Honourable [Firstname Surname].

England

Changing power of English earls

In Anglo-Saxon England (5th to 11th centuries), earls had authority over their own regions and right of judgment in provincial courts, as delegated by the king. They collected fines and taxes and in return received a "third penny", one-third of the money they collected. In wartime they led the king's armies. Some shires were grouped together into larger units known as earldoms, headed by an ealdorman or earl. Under Edward the Confessor (r. 1042–1066) earldoms like Wessex, Mercia, East Anglia and Northumbria—names that represented earlier independent kingdoms—were much larger than any individual shire.

Earls originally functioned essentially as royal governors. Though the title of "Earl" was nominally equal to the continental "Duke", unlike such dukes, earls were not de facto rulers in their own right.

After the Norman Conquest of 1066, William the Conqueror (r. 1066–1087) tried to rule England using the traditional system, but eventually modified it to his own liking. Shires became the largest secular subdivision in England and earldoms disappeared. The Normans did create new earls - like those of Hereford, Shropshire, and Chester - but they were associated with only a single shire at most. Their power and regional jurisdiction was limited to that of the Norman counts.[7] There was no longer any administrative layer larger than the shire, and shires became (in Norman parlance) "counties". Earls no longer aided in tax collection or made decisions in country courts, and their numbers were small.

King Stephen (r. 1135–1154) increased the number of earls to reward those loyal to him in his war with his cousin Empress Matilda. He gave some earls the right to hold royal castles or to control the sheriff - and soon other earls assumed these rights themselves. By the end of Stephen's reign, some earls held courts of their own and even minted their own coins, against the wishes of the king.

It fell to Stephen's successor Henry II (r. 1154–1189) to again curtail the power of earls. He took back the control of royal castles and even demolished castles that earls had built for themselves. He did not create new earls or earldoms. No earl was allowed to remain independent of royal control.

The English kings had found it dangerous to give additional power to an already powerful aristocracy, so gradually sheriffs assumed the governing role. The details of this transition remain obscure, since earls in more peripheral areas, such as the Scottish Marches and Welsh Marches and Cornwall, retained some vice-regal powers long after other earls had lost them. The loosening of central authority during the Anarchy of 1135-1153 also complicates any smooth description of the changeover.

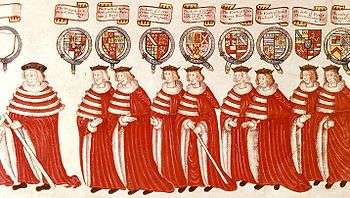

By the 13th century earls had a social rank just below the king and princes, but were not necessarily more powerful or wealthier than other noblemen. The only way to become an earl was to inherit the title or to marry into one—and the king reserved a right to prevent the transfer of the title. By the 14th century, creating an earl included a special public ceremony where the king personally tied a sword belt around the waist of the new earl, emphasizing the fact that the earl's rights came from him.

Earls still held influence and, as "companions of the king", were regarded as supporters of the king's power. They showed their own power prominently in 1327 when they deposed King Edward II. They would later do the same with other kings of whom they disapproved. In 1337 Edward III declared that he intended to create six new earldoms.[8]

Earls, land and titles

A loose connection between earls and shires remained for a long time after authority had moved over to the sheriffs. An official defining characteristic of an earl still consisted of the receipt of the "third penny", one-third of the revenues of justice of a shire, that later became a fixed sum. Thus every earl had an association with some shire, and very often a new creation of an earldom would take place in favour of the county where the new earl already had large estates and local influence.

Also, due to the association of earls and shires, the medieval practice could remain somewhat loose regarding the precise name used: no confusion could arise by calling someone earl of a shire, earl of the county town of the shire, or earl of some other prominent place in the shire; these all implied the same. So we find an "Earl of Shrewsbury" (Shropshire), "Earl of Arundel" (Sussex), "Earl of Chichester" (also Sussex), "Earl of Winchester" (Hampshire), etc.

In a few cases the earl was traditionally addressed by his family name, e.g. the "earl Warenne" (in this case the practice may have arisen because these earls had little or no property in Surrey, their official county). Thus an earl did not always have an intimate association with "his" named or implied county. Another example comes from the earls of Oxford, whose property largely lay in Essex. They became earls of Oxford because earls of Essex and of the other nearby shires already existed.

Eventually the connection between an earl and a shire disappeared, so that in the present day a number of earldoms take their names from towns, mountains, or simply surnames.

Ireland

The first Irish earldom was the Earl of Ulster, granted to the Norman knight Hugh de Lacy in 1205 by Henry II, King of England and Lord of Ireland. Other early earldoms were Earl of Carrick (1315), Earl of Kildare (1316), Earl of Desmond (1329) and Earl of Waterford (1446, extant).

After the Tudor reconquest of Ireland (1530s–1603), native Irish kings and clan chiefs were encouraged to submit to the English king (now also King of Ireland) and were, in return, granted noble titles in the Peerage of Ireland. Notable among those who agreed to this policy of "surrender and regrant" were Ulick na gCeann Burke, 1st Earl of Clanricarde, Murrough O'Brien, 1st Earl of Thomond, Donald McCarthy, 1st Earl of Clancare, Rory O'Donnell, 1st Earl of Tyrconnell, Randal MacDonnell, 1st Earl of Antrim and Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone. The earls of Tyrone and Tyrconnell later rebelled against the crown and were forced to flee Ireland in 1607; their departure, along with about ninety followers, is famed in Irish history as the Flight of the Earls, seen as the ultimate demise of native Irish monarchy.

Ireland became part of the United Kingdom in 1801, and the last Irish earldom was created in 1824. The Republic of Ireland does not recognise titles of nobility.

Notable later Irish earls include Jacobite leader Patrick Sarsfield, 1st Earl of Lucan; Postmaster General Richard Trench, 2nd Earl of Clancarty; Prime Minister William Petty, 2nd Earl of Shelburne (later made a marquess) and the murderer John Bingham, 7th Earl of Lucan.

Scotland

The oldest earldoms in Scotland (with the exception of the Earldom of Dunbar and March) originated from the office of mormaer, such as the Mormaer of Fife, of Strathearn, etc.; subsequent earldoms developed by analogy. The principal distinction between earldom and mormaer is that earldoms were granted as fiefs of the King, while mormaers were virtually independent. The earl is thought to have been introduced by the anglophile king David I. While the power attached to the office of earl was swept away in England by the Norman Conquest, in Scotland earldoms retained substantial powers, such as regality throughout the Middle Ages.

It is important to distinguish between the land controlled directly by the earl, in a landlord-like sense, and the region over which he could exercise his office. Scottish use of Latin terms provincia and comitatus makes the difference clear. Initially these terms were synonymous, like in England, but by the 12th century they were seen as distinct concepts, with comitatus referring to the land under direct control of the earl, and provincia referring to the province; hence, the comitatus might now only be a small region of the provincia. Thus, unlike England, the term county, which ultimately evolved from the Latin comitatus, was not historically used for Scotland's main political subdivisions.

Sheriffs were introduced at a similar time to earls, but unlike England, where sheriffs were officers who implemented the decisions of the shire court, in Scotland they were specifically charged with upholding the king's interests in the region, thus being more like a coroner. As such, a parallel system of justice arose, between that provided by magnates (represented by the earls), and that by the king (represented by sheriffs), in a similar way to England having both Courts Baron and Magistrates, respectively. Inevitably, this led to a degree of forum shopping, with the king's offering - the Sheriff - gradually winning.

As in England, as the centuries wore on, the term earl came to be disassociated from the office, and later kings started granting the title of earl without it, and gradually without even an associated comitatus. By the 16th century there started to be earls of towns, of villages, and even of isolated houses; it had simply become a label for marking status, rather than an office of intrinsic power. In 1746, in the aftermath of the Jacobite rising, the Heritable Jurisdictions Act brought the powers of the remaining ancient earldoms under the control of the sheriffs; earl is now simply a noble rank.

Wales

Some of the most significant Earls (Welsh: ieirll, singular iarll) in Welsh history were those from the West of England. As Wales remained independent of any Norman jurisdiction, the more powerful Earls in England were encouraged to invade and establish effective "buffer states" to be run as autonomous lordships. These Marcher Lords included the earls of Chester, Gloucester, Hereford, Pembroke and Shrewsbury (see also English Earls of March).

The first Earldoms created within Wales were the Lordship of Glamorgan (a comital title) and the Earldom of Pembroke.

Tir Iarll (English: Earl's land) is an area of Glamorgan, which has traditionally had a particular resonance in Welsh culture.[9]

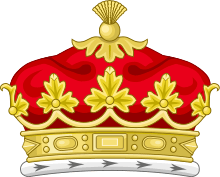

Coronet

A British earl is entitled to a coronet bearing eight strawberry leaves (four visible) and eight silver balls (or pearls) around the rim (five visible). The actual coronet is mostly worn on certain ceremonial occasions, but an Earl may bear his coronet of rank on his coat of arms above the shield.

Former Prime Ministers

An earldom became, with a few exceptions, the default peerage to which a former Prime Minister was elevated. However, the last Prime Minister to accept an earldom was Harold Macmillan, who became Earl of Stockton in 1984.

Scandinavia

| Konge (sovereign) |

| Jarl (prince) |

| Housecarl (retainer) |

| Ceorl (free tenant) |

| Freedman |

| Thrall (slave) |

Norway

In later medieval Norway, the title of jarl was the highest rank below the king. There was usually no more than one jarl in mainland Norway at any one time, sometimes none. The ruler of the Norwegian dependency of Orkney held the title of jarl, and after Iceland had acknowledged Norwegian overlordship in 1261, a jarl was sent there, as well, as the king's high representative. In mainland Norway, the title of jarl was usually used for one of two purposes:

- To appoint a de facto ruler in cases where the king was a minor or seriously ill (e.g. Håkon galen in 1204 during the minority of king Guttorm, Skule Bårdsson in 1217 during the illness of king Inge Bårdsson).

- To appease a pretender to the throne without giving him the title of king (e.g. Eirik, the brother of king Sverre).

In 1237, jarl Skule Bårdsson was given the rank of duke (hertug). This was the first time this title had been used in Norway, and meant that the title jarl was no longer the highest rank below the king. It also heralded the introduction of new noble titles from continental Europe, which were to replace the old Norse titles. The last jarl in mainland Norway was appointed in 1295.

Some Norwegian jarls:

- Skagul Toste

- Skule Tostesson, killed by peasants near Haverö church in the 12th century.

- Erling Skakke, father of king Magnus V

- Alv Erlingsson, earl of Sarpsborg and governor of Borgarsyssel.

- Haakon the Crazy

Sweden

The usage of the title in Sweden was similar to Norway's. Known as jarls from the 12th and 13th century were Birger Brosa, Jon Jarl, Folke Birgersson, Charles the Deaf, Ulf Fase, and the most powerful of all jarls and the last to hold the title, Birger Jarl.

Iceland

Only one person ever held the title of Earl (or Jarl) in Iceland. This was Gissur Þorvaldsson, who was made Earl of Iceland by King Haakon IV of Norway for his efforts in bringing Iceland under Norwegian kingship during the Age of the Sturlungs.[10]

In fiction

Earls have appeared in various works of fiction. For examples of fictional earls, see List of fictional nobility#Earls.

See also

Notes

- "Earl". Collins Dictionary. 23 September 2014. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- "Earl". Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- Stevenson, Angus, ed. (2007). Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. 1 A-M (6th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-920687-2.

- e.g. Järsberg Runestone (6th century) ek erilaz [...] runor waritu...

- Lindström (2006:113–115).

- Hughes, Geoffrey (26 March 1998). Swearing: A Social History of Foul Language, Oaths and Profanity in English. Penguin Books. ISBN 9780141954325. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- Crouch p108

- Ayton, Andrew. "Edward III and the English aristocracy at the beginning of the Hundred Years War". De Re Militari. The Society for Medieval Military History. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- Davies, John; Jenkins, Nigel; Menna, Baines; Lynch, Peredur I., eds. (2008). The Welsh Academy Encyclopaedia of Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. p. 872. ISBN 978-0-7083-1953-6.

- Jesse L. Byock (2001), Viking Age Iceland, Penguin Books, ISBN 0141937653 p. 350

References

- Crouch, David (2002). The Normans. ISBN 1-85285-387-5.

- Morris, Marc (December 2005). "The King's Companions". History Today.

- Lindström, Fredrik; Lindström, Henrik (2006). Svitjods undergång och Sveriges födelse. Albert Bonniers förlag. ISBN 9789100107895. (in Swedish)

External links

.svg.png)