Dejanović noble family

The Dejanović (Serbian Cyrillic: Дејановић, pl. Dejanovići / Дејановићи) or Dragaš (Serbian Cyrillic: Драгаш, pl. Dragaši / Драгаши)[a], originates from a medieval noble family that served the Serbian Empire of Dušan the Mighty (r. 1331-1355) and Uroš the Weak (r. 1355-1371), and during the fall of the Serbian Empire, after the Battle of Maritsa (1371), it became an Ottoman vassal. The family was one of the most prominent during these periods. The family held a region roughly centered where the borders of Serbia, Bulgaria and North Macedonia meet. The last two Byzantine Emperors were maternal descendants of the house.

| Dejanović Дејановић Dragaš Драгаш | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country | |

| Founded | 1346 |

| Founder | Dejan |

| Final ruler | Konstantin |

| Titles | gospodin ("lord") sevastokrator despot |

| Estate(s) | župe (counties) of Žegligovo and Preševo (1355) |

| Dissolution | 1395 |

The progenitor, sevastokrator Dejan, was a magnate in the service of Emperor Dušan, and also the Emperor's brother-in-law through his marriage with Teodora-Evdokija. Dejan held the župe (counties) of Žegligovo and Preševo under Dušan, and later received the title of despot during the rule of Dušan's son, Emperor Uroš V, when he was appointed the administration Upper Struma with Velbužd, after the death of powerful despot Jovan Oliver. After Dejan's death between 1358 and 1365, most of his province was given to Vlatko Paskačić, besides the initial counties of Žegligovo and Preševo, which were left to his two sons, Jovan and Konstantin. The brothers, who ruled jointly, managed to double the extent of their province during the Fall of the Serbian Empire following Emperor Uroš V's death, chiefly to the south; the lands now covered from Vranje and Preševo to Radomir, in the south to Štip, Radovište and Strumica. In 1373, two years after the devastating Battle of Maritsa, the brothers became vassals to the Ottoman Empire. After the death of Jovan in 1377, Konstantin continued to rule under Ottoman overlordship. Konstantin and his provincial neighbour and fellow Ottoman vassal, Prince Marko, fell at the Battle of Rovine in 1395.

The Dejanović family built and reconstructed several churches and monasteries throughout their province. Some of these include the Zemen Monastery and Arhiljevica Church, built by Dejan, and the Poganovo Monastery and Osogovo Monastery, built by Konstantin.

Konstantin had married his daughter Jelena to the Byzantine Emperor Manuel II Palaiologos (r. 1391-1425), from which the last Byzantine Emperors John VIII (r. 1425-1448) and Constantine XI (r. 1449-1453) sprung. Constantine XI, who died defending Constantinople from the Ottomans in 1453, was known by his mother's surname, in Greek, Dragases (Δραγάσης, tr. Dragáses).

Family

| Dejan (fl. 1345–1358/1365) Serbian nobleman, served: • Dušan (1345–1355); • Uroš V (1355–1358/1365). | Teodora-Evdokija (fl. 1345–?) Serbian princess, sister of Dušan. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Jovan (fl. 1365–†1378) Serbian nobleman, served: • Uroš V (1365–1371); • Ottoman (1371-1378). | Žarko | Teodora | Đurađ Balšić | Unknown | Konstantin (fl. 1365–†1395) Serbian nobleman, served: • Ottoman (1378-1395). | Eudokia Megale Komnene (fl. 1378–†1395) Byzantine princess. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ruđina Balšić | Mrkša | See: Balšić | Jelena (ca. 1372–1450) Byzantine Empress. | Manuel II Palaiologos (1350–1425) Byzantine Emperor. (1391-1425) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 children; John VIII Palaiologos Constantine XI Palaiologos | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

There are possible portraits of the family in their monasteries (ktetor frescoes), but it is not affirmed that these represent Dejan's family.

History

The family's progenitor was Dejan, a Serbian vojvoda (military commander and lord) in the Kumanovo region, who married Teodora, the sister of Stefan Dušan. Dejan became sevastokrator in 1346.[1] His origin is unknown.[2] Earlier scholars believed that the Dejanović were relatives of Jovan Oliver, although this is no longer accepted (Fine 1994).[3] K. Jirechek suggested that he was vojvoda Dejan Manjak.[2]

On April 16, 1346 (Easter), Stefan Dušan convoked a huge assembly at Skopje, where the autocephalous Serbian Archbishopric was raised to the status of a Patriarchate.[4] The new Patriarch Joanikije II now solemnly crowned Dušan as "Emperor (basileus) and autocrat of Serbs and Romans (Greeks)".[4] Dušan had his son Uroš V crowned King of Serbs and Greeks, giving him nominal rule over the Serbian lands, and although Dušan was governing the whole state, he had special responsibility for the "Roman", i.e. Greek lands.[4] A further increase in the Byzantinization of the Serbian court followed, particularly in court ceremonial and titles.[4] In the years that followed, the Serbian nobility were elevated: Dušan's half-brother Simeon Uroš, brother-in-law Jovan Asen and Jovan Oliver were granted the title of despot. His brother-in-law Dejan and Branko were granted the title of sevastokrator. The military commanders (voivodes) Preljub, Vojihna and Grgur received the title of ćesar.[5][6][7] The raising of the Serbian Patriarchate resulted in the same spirit - bishops became metropolitans.[5]

He is mentioned in 1354.[8] According to Stefan Dušan's charter to the monastery of Arhiljevica (August 1355), sevastokrator Dejan, whom he called his brother ("брат царства ми севастократор Дејан")[9] possessed a large province east of Skopska Crna Gora. It included the old župe (counties) of Žegligovo and Preševo (modern Kumanovo region with Sredorek, Kozjačija and the larger part of Pčinja).[10] Based on the charter, Arhiljevica was situated where the granted villages (metochion) of Podlešane, Izvor and Rućinci (Kumanovska Crna Gora) lay, in the slopes of Jezer.[11] The fact that Dejan built Arhiljevica rather than renovate it is evidence of his economical strength.[12] Dušan also granted a church, metochion, and two villages in the region on his own behalf.[12]

Dejan was one of the prominent figures of Dušan's reign and during the fall of the Serbian Empire after Dušan's death.[12][13] Under Emperor Dušan, despot Jovan Oliver, with his brother Bogdan and sevastokrator Dejan, ruled over all of eastern Macedonia.[14] He is not mentioned much in Dušan's military endeavors, although the reputation of him and his successors suggest that he was involved in most of Dušan's successes.[13] His prominence beyond Serbia is evident from the fact that Pope Innocent VI addressed Dejan in 1355, asking him to support the creation of the union between the Catholic Church and the Serbian Orthodox Church (such letters were sent to the highest nobility and the church[15]).[13]

Dejan received the title of despot sometime after August 1355, either from Emperor Dušan, who died on 20 December 1355, or his heir Uroš V,[16] most likely under the latter.[12][13] As despot under the rule of Uroš V, Dejan was entrusted with the administration of the territory between South Morava, Pčinja, Skopska Crna Gora (hereditary lands) and in the east, the Upper Struma river with Velbuzhd, a province notably larger than during Dušan's life.[13][17][18] As the only despot, Dejan held the highest title in the Empire (this had earlier been Jovan Oliver).[19]

Dejan's daughter Teodora was married to Žarko, the Lord of Lower Zeta ("gospodar donje Zete"), in 1356.[20] Together they had a son, Mrkša (born 1363).

Until the death of knez Vojislav Vojinović in December 1363, the Serbian nobility in the Greek lands showed itself more ambitious, as it held more titles (despots Dejan and Vukašin, sevastokrator Vlatko, kesar Vojihna, etc.) and greater independence (deriving from their more extensive possessions, and therefore, wealth) in relation to the nobility of the old Serbian lands.[21] While Vojislav lived, his influence secured the pre-eminence of the old Serbian nobility,[21] but after his death Vukašin quickly gained a decisive influence on the Emperor. The nobility in the old Serbian lands was not at first alarmed at this, but Vukašin's ambition and his subsequent moves woke up the simmering antagonism between the two groups.[21] It was not only Vukašin's endless ambition that paved the way to the top, as he had plenty of support from other nobles who benefited from him.[21]

Jovan Oliver and Dejan died sometime before 1365, that is when Vukašin was elevated to King as co-ruler to Emperor Uroš V.[22] Mandić believes that Dejan died in 1358, and that Vukašin (who until then was veliki vojvoda) took his place as despot, and that Jovan Uglješa became veliki vojvoda.[23] It is unlikely that Dejan took monastic vows before his death, as his children were still young.[24] His wife Teodora took monastic vows as Evdokija and lived in Strumica and Kyustendil, and she would until her death sign as "Empress", being entitled so as a female member of the dynasty.

After the death of Dejan, his province, besides the župe of Žegligovo and Upper Struma, was appropriated to nobleman Vlatko Paskačić.[21] Vukašin Mrnjavčević, of whom there are no notable mentions until 1365, became more powerful (ultimately the most powerful in Macedonia) after the deaths of Vojislav,[21] Dejan and despot Jovan Oliver (whose status in Macedonia was very high), as Vukašin's rise would have been unlikely during the lifetime of these.[20] Vukašin's younger brother Jovan Uglješa is thought to have participated in the dismemberment of Dejan's province, as he used this chance to take the provinces which bordered on the oblast (province) of Ser (Serres), which he de facto held (Empress Jelena de jure).[21] No one looked to the young sons of Dejan who would later become very important.[21] Dejan's death brought benefit to Vukašin and Uglješa, not so much in territorial expansion (which is not so sure), but because Dejan's disappearance ended any stronger candidate to counter the Mrnjavčević family.[21]

Jovan received the title of despot, like his father before, by Emperor Uroš.[25] Most of Jovan Oliver's lands were later given to the brothers.[3] It is not known why Jovan Oliver's sons did not inherit his lands; Serbian historian V. Ćorović considered turmoil and disorder the case, however not knowing the extent it developed to and what the consequences were.[20] Earlier scholars believed that the Dejanović were relatives of Jovan Oliver, although this is no longer accepted (Fine 1994).[3] The Dejanović brothers ruled a spacious province in eastern Macedonia,[25] in the southern lands of the Empire, and remained loyal to Uroš V.[3]

After the Ottoman victory at Maritsa (1371), the Ottomans did not immediately start with real conquests in the Balkans, but, reinforcing their positions, stopped to spread their influence and create grounds for further progress.[26] They did not want to cause a persistent struggle from a Christian alliance until they were fully sure, so in the beginning they were satisfied with the Balkan magnate families recognizing their sovereignty and paying them tribute, in order to increase Ottoman financial resources.[26] In that way they did not take Vukašin's province, but agreed to let his son and heir Marko rule in the Macedonia region, with the seat at Prilep (the foremost fortification of Pelagonia).[26] In the north of Vukašin's province, Marko's younger brother Andrijaš held properties.[26] Vukašin's successors fought with their western and northern Serbian neighbours, who after the death of Vukašin rushed to take over his possessions.[26]

Emperor Uroš V died childless in December 2/4 1371, after much of the Serbian nobility had been destroyed in Maritsa earlier that year. This marked an end to the once powerful Empire. Vukašin's son Marko, who had earlier been crowned Young King was to inherit his father's royal title, and thus became one in the line of successors to the Serbian throne. Meanwhile, the nobles pursued their own interests, sometimes quarreling with each other. Serbia, without an Emperor "became a conglomerate of aristocratic territories",[27] and the Empire was thus divided between the provincial lords: Marko, the Dejanović brothers, Djuradj Balšić, Vuk Branković, Nikola Altomanović, Lazar Hrebeljanović. The Balšić family took Prizren, and Vuk Branković took Skoplje, from Marko.[26]

In the new redistribution of feudal power, after 1371, the brothers despot Jovan and gospodin Konstantin greatly expanded their province.[28][29] Not only did they recreate their father's province but also at least doubled the territory, on all sides, but chiefly towards the south.[28] The brothers ruled on the left riverside of the Vardar, from Kumanovo to Strumica.[26] In 1373, two years after Maritsa, the first mentions are made on the events in the province of the Dejanović brothers, as well as their mutual relation.[30] In June 1373, on the road from Thessaloniki to Novo Brdo, some Ragusan merchants had an accident in despot Jovan's land ("in terenum despotis Dragassii").[30] Ottoman sources report that in 1373, the Ottoman army compelled Jovan (who they called Saruyar) in the upper Struma, to recognize Ottoman vassalage.[31] As Marko had done, also the Dejanović brothers recognized Ottoman sovereignty.[26] Although vassals, they had their own government.[29] The Ottoman gazi at the time conquered more than the Empire could put under its immediate control.[29] Thus it is not surprising that the brothers had built an internal administration, shared possessions, issued charters, minted coins.[29] In 1376, Konstantin took up a high position in the government, and this shows that the elder brother Jovan relatively early started to share the rule with his younger brother.[32] On June 1, 1377 the brothers wrote a charter to Hilandar, where they confirmed the earlier donations of čelnik Stanislav; the donations included the Church of St. Blasius in Štip and three villages.[33][34] In 1377 and 1380 the family issued charters to the Monastery of St. Panteleimon on Mount Athos.[35] Jovan most often signed documents of the two.[25] As the Dejanović brothers were maternally descended from the Nemanjić dynasty as grandsons of King Stefan Uroš III, they worked on expanding their rule and perhaps ultimately rule Serbia.[36] The brothers spoke of "our Empire", and their mother Teodora-Evdokija signed as Empress.[27] Their state symbol was the white double-headed eagle and they minted coins according to the Nemanjić style.[37]

Jovan died in ca. 1378,[38] before 1381.[39] Konstantin continued to rule under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire.

By 1379, Lazar Hrebeljanović, the lord of Pomoravlje, emerged as the first and most powerful among Serbian nobles. In his signatures, he titled himself as the "Autokrator of all the Serbs" (самодрьжць вьсѣмь Србьлѥмь); nevertheless, he was not powerful enough to unite all Serbian lands under his authority. Konstantin, the Balšić, Mrnjavčević, Vuk Branković, and Radoslav Hlapen, ruled in their respective domains without consulting with Lazar.[40]

Konstantin let the Ottoman army cross his province into Kosovo and also gave supporting armed bands, before the Battle of Kosovo (1389).[26]

Konstantin married, but his spouse's name is unknown.[41] Konstantin had a daughter, Jelena, who in 1392 married Byzantine Emperor Manuel II.[41][42] Although Manuel II and Konstantin maintained relations, they were of no political importance.[42] Konstantin was an Ottoman vassal, within nearest reach and always on the look from Edirne and the Sultan, and was unable to change it.[42]

.jpg)

Bayezid, having conquered south Bulgaria, saw an opportunity for the conquest of Wallachia when dissatisfied Wallachian noblemen called for Ottoman support against Mircea I of Wallachia, which he accepted.[42] Sigismund supported Mircea and helped him back to the throne, while Bayezid led a great army into Wallachia, composed also out of vassals Stefan Lazarević, Konstantin Dejanović and Marko.[42] A contemporary source, Constantine the Philosopher, wrote that Marko unwillingly joined this fight against fellow Christians, and how he said to Konstantin: "I speak and pray to the Lord that he helps the Christians, even if I would be among the first to die in the battle.".[42] In the Wallachian victory at the Battle of Rovine (17 May 1395), both Marko and Konstantin died.[42] The provinces of Marko and Konstantin became Ottoman.[42]

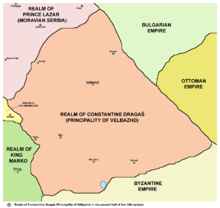

Domain of the Dejanović family

Dejan's possessions, Serbian Empire

According to Emperor Dušan's Arhiljevica charter (August 1355),[9] sevastokrator Dejan possessed the župe (counties[43]) of Žegligovo and Preševo (modern Kumanovo region with Sredorek, Kozjačija and the larger part of Pčinja).[10] As despot under the rule of Uroš V, Dejan was entrusted with the administration of the territory between South Morava, Pčinja, Skopska Crna Gora (hereditary lands) and in the east, the Upper Struma river with Velbužd (Kyustendil), a province notably larger than during Dušan's life.[13][17][18]

Jovan's and Konstantin's possessions, Ottoman Empire

Dejan's son Jovan became a vassal of the Ottoman Empire after the Battle of Maritsa (1371), and Konstantin also acknowledged Ottoman suzerainty. Their province (oblast[b]) during the fall of the Serbian Empire was roughly located between the rivers Struma and Vardar and included territories of the modern countries of Bulgaria, Serbia and North Macedonia. According to Stojan Novaković, the province "spanned from Prince Lazar's border (between Kumanovo and Preševo and the Skopska Crna Gora ridge) and then much further towards the south, as it looks, to the wreath that in the south marks the border of the waterfall of the Dojran and Bulgarian lake".[44]

There were some four disputes regarding boundaries in the Strumica region within Konstantin's province, dated year 6884 (September 1, 1375 - August 31, 1376): of the metochion (church-dependent territory) between Hilandar and Agiou Panteleimonos monastery; Hilandar and nobleman Vojin Radišić; Hilandar and Bogoslav, the lord of Nežičino village; the boundary confirmation of Prosenikov village.[45]

Economy

The brothers minted coins according to the Nemanjić style, and used the white double-headed eagle (Serbian eagle).[37]

The province of the brothers had business with foreign merchants, and besides the domestic currency there was also Venetian moneta in circulation.[29] The important Via de Zenta trade route connecting the Adriatic with Serbia crossed this region; it was used for the trade between Republic of Venice and Ragusa and Serbia and Bulgaria. It started in the Zetan ports and towns, continued along the Drin Valley to Prizren, then to Lipljan, then through Novo Brdo to Vranje and Niš. The road ended its use with the Ottoman conquest of Serbia.

They had vast mines in Kratovo (until 1390) and Zletovo.

Aftermath and legacy

Konstantin married, but his spouse's name is unknown,[41] and from this marriage Konstantin had a daughter, Jelena, who in 1392 married Byzantine Emperor Manuel II Palaiologos (r. 1391-1425).[41][42] Manuel II and Jelena had several children, among whom were the last Byzantine Emperors John VIII (r. 1425-1448) and Constantine XI (r. 1449-1453).[46] Constantine XI, the last Byzantine Emperor,[47][48][49] who died defending Constantinople from the Ottomans in 1453, was known by his mother's surname, in Greek, Dragáses (Δραγάσης).[50] Constantine XI was named after his grandfather.[51]

Konstantin Dragaš is attested in Serb epic poetry as "beg Kostadin", as a friend of Prince Marko.

Kyustendil, even in its turkified name, still keeps the memory of its lord, Konstantin.[26] Turkish custendil means "Konstantin's bath/spa".

The Kumanovo region (old Žegligovo) received its geographical location and certain settlement picture in the 14th century, during the rule of the Nemanjić and Dejanović.[52]

Buildings

Fortifications

Church buildings

The Dejanović family built and reconstructed several churches and monasteries throughout their province. Some of these include the Zemen Monastery and Arhiljevica Church, built by Dejan, and the Poganovo Monastery and Osogovo Monastery, built by Konstantin. View the collapsible list below for a complete overview of church buildings that were located in the family's province.

| List of church buildings in the Province | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name, location | Founded | Notes | Image |

| Spasovica,[53] in Velbužd (modern Kyustendil) |

1330, by Stefan Uroš III | Built in honour of the victory at the Battle of Velbazhd against the Bulgarians, on the location where King Stefan prayed in his tent the night before the battle. | |

| Church of St. George,[53] in Koluši (modern Kyustendil) |

Seat of the local Metropolitanate. | ||

| Church of Gospođino Polje,[53] in Koluši |

14th century | ||

| Church of the Annunciation,[53] in Slokoštica (modern Kyustendil) |

1378-1395 | Built during the rule of Konstantin | |

| Church of St. Nicholas,[53] in Slokoštica |

1378-1395 | Built during the rule of Konstantin | |

| Church of the Sts. Archangels,[53] in Slokoštica |

1378-1395 | Built during the rule of Konstantin | |

| Church of St. Demetrius,[53] in Slokoštica |

1378-1395 | Built during the rule of Konstantin | |

| Church of St. Parascheva,[53] in Slokoštica |

1378-1395 | Built during the rule of Konstantin | |

| Church of St. John the Baptist (Zemen monastery),[53] in Zemen (modern Pernik Province) |

by Dejan | Built on the ruins of an earlier 11th-century church. There are ktitor frescoes depicting Dejan in the monastery. | |

| Church of St. John the Baptist (Poganovo monastery),[53] in Poganovo (modern Pirot District) |

1378–1395, by Konstantin |  | |

| Churches in Tran and Breznik[53] | 1378–1395, by Konstantin | ||

| Lesnovo monastery,[53] in Lesnovo (modern Probištip) |

1341, by Jovan Oliver |  | |

| Church of St. Demetrius,[53] in Zletovo (modern Probištip) |

14th century | ||

| Church of St. Nicholas,[53] in Zletovo |

14th century | ||

| Pirog monastery,[53] in Zletovo |

14th century | ||

| Monastery of St. Joachim of Osogovo,[53] in Kriva Palanka |

1378–1395, by Konstantin | Endowment of Konstantin. | |

| Church of St. Nicholas (Psača monastery),[53] in Psača |

ca. 1358, by Vlatko Paskačić |  | |

| Church of Sts. Archangels (Rila monastery),[53] in Štip |

ca. 1334, by Hrelja | Hrelja built the church on the location of an older 10th-century monastery. | |

| Church of Holy Salvation,[53] in Štip |

1369, by Dmitar | Built by a Dejanović relative, Dmitar. | |

| Church of St. Nicholas,[53] in Štip |

14th century | ||

| Church of St. John the Baptist,[53] in Štip |

14th century | ||

| Church of St. Demetrius,[53] in Kočani |

by Jovan Oliver | ||

| Church of St. George,[53] in Staro Nagoričane |

1313, by Stefan Milutin | Built on the location of an earlier Byzantine church built in 1071. | |

| Church of the Holy Mother of God,[53] in Arhiljevica |

1349, by Dejan | ||

| Church of the Holy Mother of God (Matejić monastery),[53] in Matejče |

1331-1355 | The "Church of the Holy Mother of God of the Black Mountain" in the Matejić (Matejče) mountain was reconstructed during the rule of Stefan Dušan, and is today known as the Matejić monastery. | |

| Church of St. Nicholas,[53] in Norča, Preševo |

by Neofit | Built by monk Neofit. | |

| Church of St. Prohor of Pčinja,[53] in Pčinja |

by Stefan Milutin | Built on the location of an earlier 11th-century monastery built by Byzantine Emperor Romanos IV Diogenes (r. 1068–1071). | |

| Church of St. Nicholas,[53] in Pčinja |

by Stefan Milutin | Later reconstructed by Dušan. | |

Annotations

- ^ The family is known as Dejanović (Дејановић) and Dragaš (Драгаш); Dejanovići, Dragaši in plural (Дејановићи, Драгаши). Their family name in historiography, Dejanović, is derived from the progenitor Dejan. Jovan, the son of Dejan, usually signed himself "despot Jovan Dragaš", or simply "despot Dragaš", while only one document mention Konstantin by this name.[54] The Dragaš name was thus used by Jovan and Konstantin, and Jelena's son Constantine XI.[54] There is possibility that Dejan also used this name.[54]

- ^ It is known in historiography as the province of the Dejanović family (Serbian: област Дејановића) or province of the Dragaš family (област Драгаша). In Bulgarian sources it has also been rarely referred to as Duchy of Velbazhd (Bulgarian: Велбъждско княжество), Duchy of Kyustendil (Кюстендилско княжество) and Duchy of the Dragaš (Княжество на Драгаши[55]).

References

- Jakov Ignjatović, Živojin Boškov 1987, Odabrana dela Jakova Ignjatovića Vol. 1, p. 548:

Дејановићи, српска феудална породица. Оснивач јој је војвода Дејан, од 1346. г. севастократор, војни заповедник цара Душана. Жена му је била Душанова сестра. Управ- љао је кумановском облашћу. Синови су му били Констаи- ...

- Mihaljcic 1975, p. 67

- Fine 1994, p. 358

- Fine 1994, p. 309

- Fine 1994, p. 310

- Ćorović 2001, ch. 3, VII. Stvaranje srpskog carstva

- Fajfric, 39. Car Dušan

- Miklosich, Monumenta Serbica, p. 143

- Mandić 1986, p. 161:

У повељи манастиру Архиљевици, издатој ав- густа 1355. године, Душан на три места каже: „Брат царства ми севастократор Дејан". Именица брат има вишеструко значење. Најодређеније је оно примарно: рођени брат.

- Историско друштво НР Србије 1951, pp. 20-21:

према повељи манастиру богоро- дичимог ваведења у Архиљевици,50 држао као своју баштину пространу област иеточно од Скопске Црне Горе. Она је обухватала старе жупе Прешево и Жеглигово (данас кумановски крај са Средореком, Козјачијом...

- Vranjski glasnik, Vol. 19-20, p. 169:

Севастократор Дејан, зет цара Душана по сестри Теодори (у калуђерству Евдокији), држао је кумановско-прешевску удолину, а то је део самог језгра Балкана. [...] „Брат царства ми севастократор Дејан"\ Судећи према овој повељи, Архиљевица се налазила тамо где су дарована села Подлешане, Извор и Рућинци, а то је Куманов- ска Црна гора, односно падине Језерске планине.

- Mihaljčić 1989, pp. 79–81

- Fajfric, 42

- Soulis p. 101

- Soulis p. 53

- Soulis 1984, p. 190

- Mihaljčić 1989, p. 81:

Дејанова баштина — жупе Жеглигово и Прешево — простиру се између Пчиње, Јужне Мораве и Скопске Црне горе. Источно од Жеглигова и Прешева, око горњег тока Струме са Велбуждом, простирала се „држава" севастократора Дејана

-

... старе жупе Жеглигово (са данашњом Козјачијом, Средореком и највећим делом Пчиње) на истоку и Прешево са једним делом Гњиланског Карадага на западу. Оно се није ограничавало само на кумановски крај — Жеглигово — ...

- Mandić 1986, p. 143:

То је био дота- дашњи севастократор Дејан. Поставши деспот све српске, поморске и грчке земље (али не велики деспот, јер је после Оливера у Урошевој држави увек био само један деспот, па није ни било усло- ва за великог), ...

- Ćorović 2001, ch. 3, IX. Raspad Srpske Carevine

- Fajfric, 45. Braća Mrnjavčević

- Mandić 1986, p. 144

- Mandić: Тако би 1358. година била прекрет- ничка за неке великаше: те године деспот Дејан је умро,13 на његово место дошао је вероватни дота- дашњи велики војвода Вукашин, а на место вели- ког војводе дошао је Јован Угл>еша.

- Mandić 1990, p. 155

- Samardzic 1892 p. 22:

Синови деспота Дејана заједнички су управљали пространом облашћу у источној Македонији, мада је исправе чешће потписивао старији, Јован Драгаш. Као и његов отац, Јован Драгаш је носио знаке деспотског достојанства. Иако се као деспот помиње први пут 1373, сасвим је извесно да је Јован Драгаш ову титулу добио од цара Уроша. Високо достојанство убрајало се, како је ...

- Ćorović 2001, ch. 3, XIII. Boj na Kosovu

- Ross-Allen 1978, p. 505

- Михаљчић 1975, p. 174

- Историјски гласник Друштва историчара СР Србије 1994, p. 31

- Зборник радова Византолошког института 1982, p. 198

- Edition de lA̕cadémie bulgare des sciences, 1986, "Balkan studies, Vol. 22", p. 38

- Зборник радова Византолошког института 1982, p. 199

- "Povelja braće Dragaša Hilandaru o Crkvi Sv. Vlasija". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Зборник радова Византолошког института 1982, p. 200

- Српско учено друштво, pp. 249-254

- Čupić 1914, p. 159

- Čupić 1914, p. 228

- Srpsko geografsko društvo 1987, p. 77

-

Брат његов Јован Драгаш умро је бно пре 1381 године (О кнезу Лазару, I. Руварац стр. 106-109)

- Mihaljčić 1975, pp. 164-165, 220

- Зборник радова Византолошког института 1982, p. 201

- Ćorović 2001, ch. 4, I. Srbi između Turaka i Mađara

- Fine 1991, p. 304

- Ostrogorski, p. 459:

Према Ст. Новаковићу, област Дејановића се „ширила од кнез Лазаревих граница (између Куманова и Прешева и слемену Црне Горе) па доста далеко к југу, како изгледа, до венаца што с југа граниче водопађу Дојранског и Бугарског Језера.

- Sporovi oko zemljišta i međa u oblasti Konstantina Dragaša

U oblasti gospodina Konstantina Dragaša, na širem području oko reke Strumice vođeno je nekoliko sporova oko zemljišnih međa u toku 6884 (1375. septembar 1 - 1376. avgust 31, indikt XIV) godine. Sačuvana je isprava o četiri spora i načinu njihovog rešavanja u njegovoj oblasti. Sporovi su vođeni između Hilandara i ruskog manastira Sv. Pantelejmona ili Rusika, manastira Hilandara i vlastelina Vojina Radišića, manastira Hilandara i Bogoslava, gospodara sela Nežičino. Četvrti sastavni deo isprave odnosi se na utvrđivanje međa sela Prosenikova.

- Andrews 2006, Castles of the Morea, p. 259

Five sons of Manuel II: John VIII, Constantine XI, Theodore, Thomas, and Demetrios, last family of reigning Emperors at Constantinople and Despots of Mistra.

- The last centuries of Byzantium, 1261–1453 Donald MacGillivray Nicol – Cambridge University Press, 1993 p.369

- History of the Byzantine Empire, 324–1453, A.Vasiliev – 1958, volume 2 p.589

- World History, William J. Duiker, Jackson J. Spielvogel 2009, Volume I p.378

- Geōrgios Phrantzēs 1985, p. 93

Constantine XI Dragases, so named after his mother Helen, of the Serbian dynasty of Dragas in East Macedonia. She was the daughter of Prince Constantine Dejanovic and a niece of the Despot John Dragas.

- Head, Constance (1977), "+Manuel+and+helena" Imperial Twilight: The Palaiologos Dynasty and the Decline of Byzantium, Nelson-Hall, p. 145,

"Constantine" was a good name, Manuel and Helena believed; for one thing, it was the name of Helena's father.

- Srpsko geografsko društvo 1972, p. 123:

Као што се зна, тада је ова област — старо Жеглигово до- била учвршћен географски положај и одрећену насеобинску слику

- Petković 1924

- Ostrogorski 1971, pp. 271-274

- Княжеството на Драгаши: Към историята на Североизточна Македония в предосманската епоха

Sources

- Ćorović, Vladimir (2001). Istorija srpskog naroda (Internet ed.). Belgrade: Ars Libri.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fajfrić, Željko (2000) [1998], Sveta loza Stefana Nemanje (in Serbian), Belgrade: "Tehnologije, izdavastvo, agencija Janus", "Rastko"

- Fine, John Van Antwerp (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-08260-5.

- Ostrogorski, Georgije. Сабрана дела (in Serbian). Prosveta.

- Samardžić, Radovan (1892). Istorija srpskog naroda: Doba borbi za očuvanje i obnovu države 1371-1537 (in Serbian). Srpska knjiiževna zadruga. ISBN 86-379-0476-9.

- Soulis, George Christos (1984). The Serbs and Byzantium during the reign of Tsar Stephen Dušan (1331-1355) and his successors. Dumbarton Oaks Library and Collection. ISBN 978-0-88402-137-7. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- Srpsko geografsko društvo (1972). Glasnik 52 (in Serbian). Srpsko geografsko društvo.

- Историско друштво НР Србије (1951). Историски гласник (in Serbian). Научна књига.

- Mihaljčić, Rade (1989) [1975]. Kraj srpskog carstva (in Serbian). Beogradski izdavačko-grafički zavod.

- Petković, Dr Vlad. R. (1924). Stari srpski spomenici u Južnoj Srbiji (in Serbian). Projekat Rastko.

- Rajičić, Miodrag (1954) [1952], "Osnovno jezgro države Dejanovića", Istorijski časopis, Belgrade: Historical Institute, 4, ISSN 0350-0802 (in Serbian)

- Živojinović, Mirjana (2006), Dragaši i Sveta Gora (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-05-02

- Милош Благојевић, Закон господина Константина и царице Јевдокије, Зборник радова византолошког института XLIV, Београд 2007. (Unused in article)

- Иван M. Ђорђевић, Зидно сликарство српске властеле у доба Немањића, Београд 1994. (Unused in article)

- M. Rajicic, Sevastokrator Dejan, in «Jugoslovenski Glasnik», 3-4 (1953) 17–28. (Unused in article)

- М. Шуица, Немирно доба српског Средњег века, Властела српских обласних господара, Београд 2000. (Unused in article)

- Велбълждско княжество в Енциклопедия България, Българската академия на науките, София, 1978, том 1 (Unused in article)

- Велбъждско княжество и Константин Драгаш в Енциклопедичен речник Кюстендил, Българската академия на науките, София, 1988 (Unused in article)

- Istoriski časopis, Vol. 4 (Unused in article)